Certainly one of the most important memorials at Green-Wood is New York City’s Civil War Monument. Yet, though that monument has been a prominent feature at Green-Wood for almost 150 years, not until now that have we been able to determine who its sculptor was.

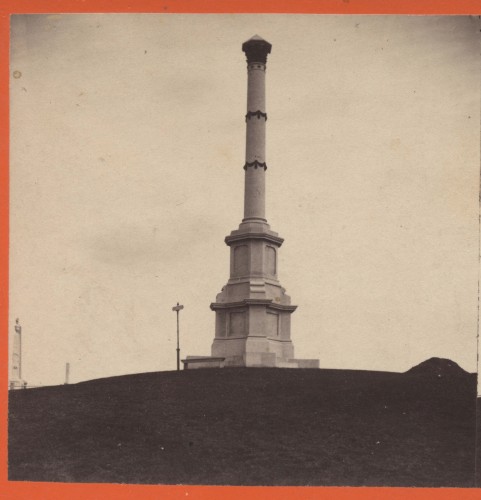

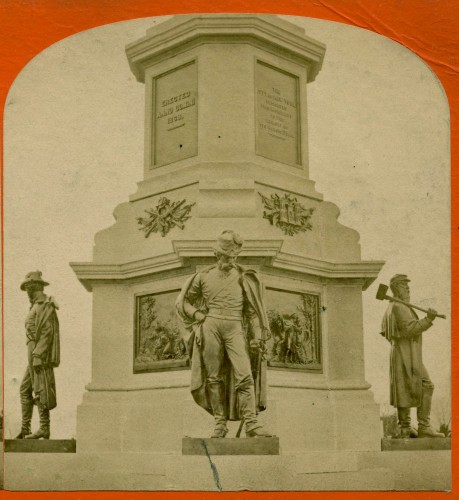

Green-Wood’s Civil War Soldiers’ Monument was constructed between 1866 and 1876. A report in The New York Times on March 15, 1866, states: “A communication was received from the Comptroller of Greenwood Cemetery, stating that in accordance with the request of the Common Council, a plot of ground has been set apart in the Cemetery, for the erection of a monument to the soldiers killed in the late war.” Further, The New York Times report of May 29, 1876, on the dedication of the monument a day earlier, includes this: “The work on this monument was begun about 10 years ago, and it was not finished until last November.” Though an inscription on a bronze plaque on the monument states that it was “erected” in 1869, it appears that that may be accurate for the granite of the monument, but not for the zinc soldiers (painted to look like bronze) and the bronze trophies and plaques that adorn the monument. We know that the monument was not unveiled until May 28, 1876–the Times and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported the next day on its dedication. This delay of several years in completing work on the monument is likely a function of installing the monument’s granite and then waiting for the zinc soldiers (four of them, one for each of the branches of the United States Army: infantry, artillery, cavalry, and pioneers/engineers), the bronze plaques (four scenes related to the Civil War) and the four bronze trophies (depicting military equipment and banners) to be created and installed.

This monument honors the 148,000 New York City men who fought “in aid of the war for the preservation of the Union and the Constitution.” It is very early for a Civil War monument; the Civil War ended in 1865. Civil War monuments more typically date from the 1880s and 1890s. And it is remarkable that New York City chose to place its Civil War Monument outside of New York City–in what was then the separate City of Brooklyn.

Here’s what the bottom sections of the Civil War Soldiers’ Monument looked like soon after they were completed:

And here’s what the monument looks like today–with it reproduction bronzes replacing the original zincs and bronzes–that were installed in 2002:

When The Green-Wood Historic Fund, with funding help from the New York City Council, restored this monument 2001-2002, using the badly-deteriorated original zinc soldiers to create molds from which were cast reproduction bronzes and working from photos to recreate the four bronze trophies above and between those soldiers that had disappeared, we were unable, despite substantial research, to determine who the sculptor of this monument was. And the mystery has remained unsolved until today.

Carol A. Grissom, the senior objects conservator at the Smithsonians’ Museum Conservation Institute, in her groundbreaking and encyclopedic work, Zinc Sculpture in America, 1850-1950 (published in 2009), discussed New York City’s Civil War Soldiers’ Monument at Green-Wood at length:

The first Civil War monument that displayed soldiers made of zinc was erected at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery . . . . Decorated with four statues, the City of New York Civil War Monument (1869) memorialized the 148,000 New Yorkers . . . Among Civil War statues made of zinc, the statues are exceptional in representing different branches of the military and in being placed in a major city. Most others would be commercial replicas of lone infantrymen erected in small towns.

Grissom went on to opine that, based on stylistic resemblances to known works by “[t]he European-born Caspar Buberl (1834-99), [he] seems the likely sculptor.” She further pointed out that a very similar and contemporary Civil War monument at Calvary Cemetery, with a different layout but including the same four soldiers in bronze, “has been attributed to the bronze founder Maurice Power and stone cutter Daniel Draddy after a design by James Goodwin Batterson (1823-1901).”

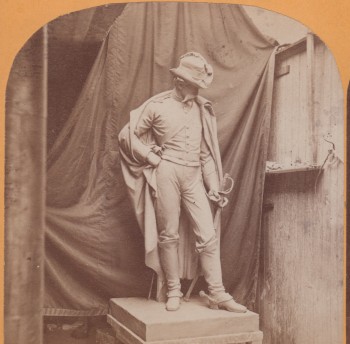

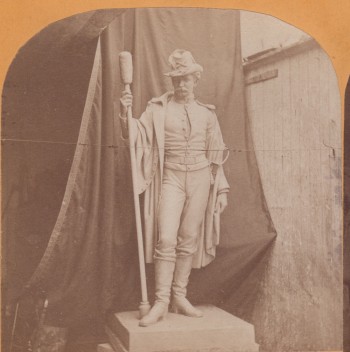

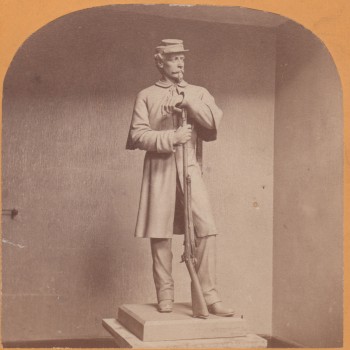

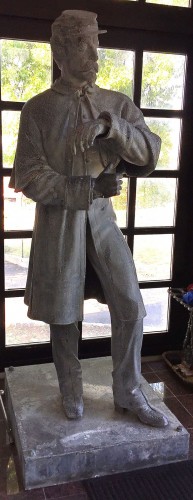

Now I have been able to solve the mystery of the sculptor of New York City’s Civil War Soldiers’ Monument at Green-Wood. I recently was able to purchase, on behalf of The Green-Wood Historic Fund, three stereoscopic views of what appeared to be the same soldier sculptures as those on the Green-Wood monument. But it was not until I was able, as I worked on this blog post, to put one of the images from the stereographic view side-by-side with photographs of the original zinc soldiers that I could determine that they were identical in form. Take a look at the three pairs below; on the left is an image from a stereoview, on the right a photograph of Green-Wood’s zinc soldiers as they appear today:

After studying the details of these three pairs, comparing the recently-acquired photographs to the zinc soldiers that made up Green-Wood’s Civil War monument, I conclude that the designs of each of the pairs match. Body positions, arm positions, folds in the uniforms, including the draping of capes and folds in pants, etc.: it all matches. Therefore, if we were able to figure out who sculpted the soldiers in the photographs at the left of the pairs above, we would know who sculpted the Green-Wood soldiers that are shown above, at right.

And, thanks to information hidden in one of the photographs at left, now we do know that.

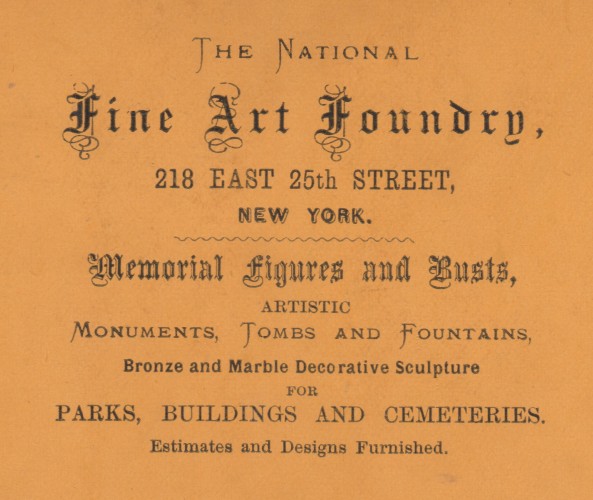

We do have some information pertaining to the manufacture of these four soldiers. Here is the text that appears on the back of each of the three stereoscopic views:

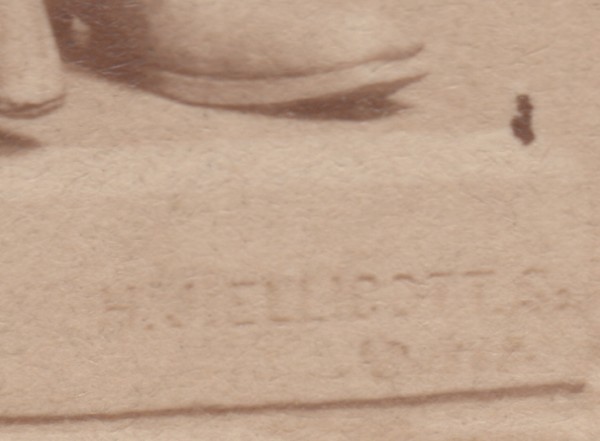

However, this identification of the foundry that cast the soldiers does not solve the mystery of the identity of the sculptor. That requires a closer look at these stereoviews. And that is exactly what I did when I received these photographs–I went over them with a 10x magnifier. Right where one might expect to find the signature of the sculptor, at front lower right on the base, I thought I saw lettering. Taking a further look, here’s what I found on the stereoscopic view of the Infantryman:

H.J. ELLICOTT, SC.–with SC. for sculptor. Indeed, a sculpture of Charles Evans, founder of the Charles Evans Cemetery in Reading, Pennsylvania, is signed “ELLICOTT SC.” There may be some lettering below this line in the photograph above, but I am unable, even under magnification, to make it out.

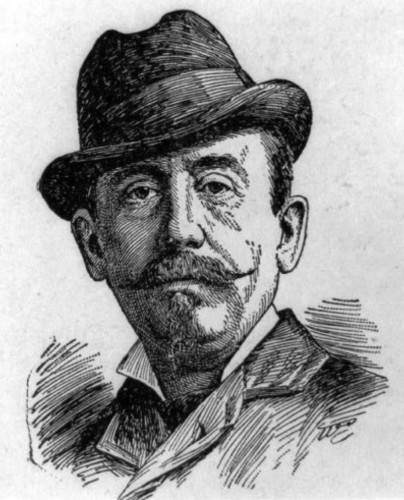

So, I searched online for a sculptor by the name of H.J. Ellicott–I had never heard that name before–and eureka! Henry J. Ellicott was a prominent sculptor of the time. Sufficiently prominent that more than a century after his death, he has his own Wikipedia page!

Ellicott was born in 1847 in Annapolis, Maryland. He was, according to his Wikipedia entry, “best known for his work on Civil War monuments.” He studied at Georgetown Medical College, then, at age 19 (likely 1868), created a larger-than-life statue of Abraham Lincoln which was on exhibition in the United States Capital rotunda for two years. From 1867 into 1870 he studied at New York City’s National Academy of Design. He was creating monuments for placement in cemeteries as early as 1870–and, according to the United States census of 1870, he was living in Manhattan and was identifying himself as a sculptor–not as a student. In the 1876 New York City directory, he is again listed as a sculptor. In addition to his portraits of many prominent men, he specialized in Civil War monuments; seven are known to be by him. Those were created between 1875 and 1894. Records of J.W. Fiske Architectural Metals, Inc., of New York City, list the sculptor of the Civil War “Infantryman” that it mass-produced as “Allicot”–this is likely a misspelling of Ellicott. Henry Jackson Ellicott was appointed chief modeler and sculptor for the U.S. Treasury Department in 1889, and in that position was responsible for all federal monuments. He died in 1901.

Notably, it appears that Ellicott was in New York City, working as a sculptor, during the period when Green-Wood’s Civil War monument was created. Though an inscription on that monument states that it was “erected” in 1869, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published its account of the dedication of the monument on May 29, 1876. It reported that the dedication had occurred on the day before, May 28, and led with this: “Five thousand persons witnessed, at Green-Wood, yesterday afternoon, the dedication and decoration of the monument erected by the City of New York, in honor of the deceased heroes of the rebellion.” Therefore, Ellicott anywhere between 22 and 29 years old when these sculptures likely were created–an appropriate age for its sculptor.

Further, in “The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans,” it is reported about Ellicott that “. . . his first commission was a monument in Calvary cemetery in 1870, followed by one in Greenwood cemetery.” This is intriguing because, as noted above, the Civil War monuments at Calvary and at Green-Wood, though different in layout and metals, each have 4 soldiers who are identical in design with their counterparts at the other cemetery. Therefore, attribution in this dictionary of both to the same sculptor–Henry Jackson Ellicott–makes sense.

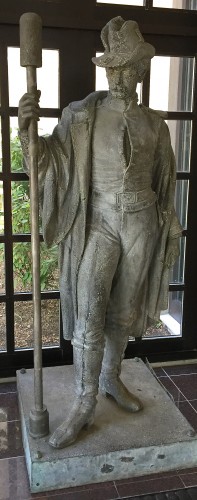

Now take a look at the Infantryman that stands in Lawrence, Massachusetts (at left). Carol Grissom, in her book about zinc, notes that the above Lawrence “Infantryman” is attributed to Henry J. Ellicott. Compare the Lawrence Infantryman to Green-Wood’s Infantryman at right–which was recast in 2002 using Green-Wood’s original zincs to create molds for bronze castings.

Note the overall similarities of the two infantrymen above. For instance, the same positioning of the cape behind his right shoulder and the same folds of the sleeve on the right arms. Admittedly, the angle of the musket is different from one to the other; however, that is of no consequence–that angle on the Green-Wood Infantryman is a function of the restoration of the equipment held by the figure, whose musket was missing when the restoration was undertaken and was created and placed separately from the recasting from the original zincs.

Further, according to a report by the Massachusetts Historical Commission from 2010, the Town of Holyoke’s Civil War Monument was sculpted by Henry J. Ellicott. That monument, constructed in 1876–the same year as the dedication of Green-Wood’s monument–is topped by a bronze of Liberty–clearly a very different figure from the Infantryman at Green-Wood and at Lawrence. Nevertheless, as per the Massachusetts Historical Commission, the Holyoke Monument has “[f]our bronze plaques in high relief on the four faces of the monument base were more specifically military in theme, but demonstrated the human cost of war.” Looking at these Ellicott-sculpted plaques in the photographs included in the commission report, I realized that they match those on Green-Wood’s Civil War Soldiers’ Monument. Here’s a side-by-side comparison, with the Holyoke plaques at left and the Green-Wood plaques (reproductions of the originals) at right:

One further note: Maurice J. Powers ran the foundry identified and advertised on the back of the three stereoscopic views of the sculpted soldiers shown at the beginning of this blog post: The National Fine Art Foundry on 25th Street in Manhattan. We know that Powers worked on the Calvary Civil War Soldiers’ Monument; now we know that he worked with Ellicott on the soldiers at Calvary and at Green-Wood. According to the Massachusetts Historical Commission’s report on the Holyoke Civil War Monument, Powers cast the bronze plaques there that Ellicott designed. They seem to have collaborated on many projects.

I have just shared these discoveries with Carol Crissom of the Smithsonian, the expert of all things zinc in 19th century America. She comments:

The discovery of the stereopticon image of the Infantryman statue at the National Fine Art Foundry with the sculptor’s name inscribed on the base – “H. J. ELLICOTT SC.” – is exciting. The Infantryman is a seminal statue. Not only is it one of four military figures on the City of New York Civil War Monuments in Calvary and Green-Wood Cemeteries and a Civil War monument in White Plains, but it also spawned three other statues of slightly different forms sold as replicas by the J.W. Fiske Iron Works, J.L. Mott Iron Works, and W.H. Mullins. The Fiske statue, which was cast in zinc and painted in imitation of bronze, is known in 18 copies. The Mott statue, also cast in zinc and painted in imitation of bronze, is known in 16 copies. The Mullins statue, which was stamped in sheet copper, is known in many copies, such as one on a Confederate Memorial in Greensboro, North Carolina.

The statue of the Infantryman and those of the Cavalryman and Engineer on the City of New York Civil War Monuments in stereopticon images taken at the National Fine Art Foundry are most likely plaster studio models made from original models sculpted in clay or possibly wax. The surfaces appear painted, with slight scuffing seen on the musket butt. They are relatively light in value compared to wood and the dark cloths in the images and do not have the gloss of bronze. Plaster models would probably have been cut at the foundry into pieces for patterns, and the patterns would have been pressed in sand to make impressions for casting metal. Flasks for sandcasting can be seen to the right of the figure of the Engineer. Note that the base of the Infantryman plaster is beveled unlike any of the metal copies, but it would have been an easy matter to cast it square in metal.

The mystery of the Infantryman’s sculptor stems from the absence of an inscription on any of the copies. While researching my book, Zinc Sculpture in America, I had seen a reference to Ellicott as the sculptor of the same statue of an Infantryman on the Civil War Monument (1881) in Lawrence, MA, in the files of the Inventory of American Sculpture [page 110 of Maurice B. Dorgan’s 1918 book Lawrence Yesterday and Today (1858-1918): A Concise History of Lawrence Massachusetts]. However, that attribution did not seem sufficient for several reasons:

1) I went to Lawrence and found “M.J. POWER/ BRONZE FOUNDER N.Y.” inscribed on the side of the Infantryman’s base but not the sculptor’s name. In contrast, the Sailor and Cavalry figures on the monument bear inscriptions for both the foundry and William O’Donovan on the front of their bases.

2) Henry Jackson Ellicott (1847-1901) would have been only 19 years old in 1866, the usual date given for the City of New York Civil War Monument in Calvary Cemetery. Moreover, the sculptor attended Georgetown Medical College in Washington, DC, and then studied at the New York Academy of Design from 1867 to 1870 according to James M. Goode [Washington Sculpture (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2002), 775]. He is said to have studied at the art school with Emanuel Leutze and Constantino Brumidi, both painters, and it is unclear where and when he received sculptural training.

3) The Fiske statue was attributed to “Allicott,” which I assumed was a corruption of Ellicott and meant that had modeled the company’s slightly different version of the statue.

4) The same statue (apart from “CS” on the cartridge case instead of “US”) on a Confederate Monument (1872) in Wilmington, North Carolina, had been attributed to O’Donovan, although I concluded that O’Donovan was more likely the sculptor of reliefs on the monument.

Now that the stereopticon image of the Infantryman statue makes an attribution to Ellicott definitive, it highlights questions about dates of installation of the statues on the City of New York Monuments. In fact, completion of the monument in Green-Wood Cemetery is said to have occurred only in November 1875 (“The Soldiers’ Monument: The dedication and decoration of the monument in Green-Wood Cemetery,” New York Times, May 29, 1876), although the date of the monument is usually given as 1869, probably the date of installation of stone elements. No documentation for the date of installation of the statues on the monument in Calvary Cemetery has been found, although an even earlier date (1866) is normally given for that monument. Other copies of the Infantryman indicate a date of 1872 or earlier. Two copies are dated 1872: the bronze statue in Wilmington and a zinc copy in White Plains. Two other bronze copies are dated 1875: in Menands, NY, and Clinton, MA; a third is dated 1887 in Ossining, NY.

The full-scale plaster models would have been made shortly before casting in metal, and based on the dates of other copies, the figures could have been modeled as late as 1872 unless an earlier date for installation of the Calvary statues can be found. By then, Ellicott would have been 25 years of age, a more likely age for his modeling of the figure. The question remains as to why Ellicott’s name was never included on any of the copies, but sculptor’s names were not invariably inscribed on statues they created. An alternative explanation – that Ellicott had a falling out with Power – seems obviated by the fact that Ellicott’s statues were cast by the foundry for monuments in Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1876 and Lawrence in 1881.

Attribution of the Infantryman to Ellicott does not mean that the other three statues on the monument were modeled by the sculptor. The Lawrence monument cast by the National Fine Art Foundry, for example, has statues by both O’Donovan and Ellicott. Other figures on the monument, particularly the Cavalryman and Artilleryman, seem closer in style to another artist, e.g., Caspar Buberl (1834-1899). As an aside, I would note that since my book was published in 2009, I have located a second bronze copy of the Cavalryman in Urbana, Ohio.

This attribution also does not change my theory that the copper-plated zinc statues on the City of New York Civil War Monument in Green-Wood Cemetery were cast by the primary zinc founder in New York, Moritz J. Seelig. His descendants claim that the zinc Infantryman in White Plains was cast at Seelig’s foundry, and Seelig is known to have electroplating capacity. In addition, the foundry almost certainly cast the variations of the Infantryman in zinc for J.W. Fiske and the J.L. Mott Iron Works.

Here are two of Ellicott’s well-known sculptures from later in his career:

It has been a mystery, since the 1876 dedication of New York City’s Civil War Soldiers’ Monument at Green-Wood: who was its sculptor? Now we know, at least in part: Henry Jackson Ellicott. It seems clear that Ellicott sculpted the Infantryman at Green-Wood and the four bronze plaques on Green-Wood’s monument. Did he sculpt all four of the zinc soldiers and all of the bronze trophies on that same monument? I tend to believe that he did. Carol Grissom thinks that another sculptor may have created the other three zincs. More research to do!

Update: This blog post went up earlier today. I have already heard from two readers who have done research on Ellicott. Historic Fund member Joe Halpern searched the Brooklyn Eagle online and found an article from September 10, 1893, about Ellicott the sculptor and his Washington, D.C. studio. It includes this: “Some of Mr. Ellicott’s work may be seen in Green-wood (sic) Cemetery, as he did the figures of the soldiers and sailors monument there.” Cara Lowery found Ellicott’s obituary in a Washington newspaper which confirmed his work on the Holyoke Monument. She found that Ellicott is interred at Rock Creek Cemetery in D.C. and has created a FindaGrave memorial for him.