There are many heroes at Green-Wood. Some are now dead. Some are still alive. Some were heroes because they bravely did their job. Others were heroes because they saw a job that needed to be done and took it upon themselves to do it. Heroes have stepped up to many challenges during Green-Wood’s 182 year history, offering themselves to help others. What do heroes have in common? They head towards danger–towards conflict–to selflessly make things better for others.

Implicit in being a medical doctor is helping others. In 1863, Dr. Clemence Lozier (1813-1888) (section 152, lot 19173) founded the first medical school in New York State to train women as doctors.

The grandson of the most famous surgeon in the world, after whom he was named, Dr. Valentine Mott (1852-1918) (section 98, lot 6035) went to Paris to work with Louis Pasteur on a vaccine for rabies. Pasteur allowed Mott to bring a inoculated rabbit home to America with him, and Mott pioneered treatment for rabies.

The Hospital for Special Surgery, today a Manhattan bastion of topflight medical treatment, was founded in the 1860s as the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled. In 1870, under the direction of Dr. James Knight (1810-1887) (section 92, lot 3155), who had founded the hospital and served as its first surgeon-in-chief, a new 200-bed hospital, the interior of which Knight designed, opened at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street.

Doctors A. Damien Martin (1934-1991) and Emery Hetrick (1930-1987) (together in section 99, lot 44519) were longtime gay activists who, in 1979, founded what is now called the Hetrick-Martin Institute for LGBTQ+ Youth–to help others.

Doctors Abram Jacobi (1830-1919) (for whom Jacobi Hospital in the Bronx is named; it today is serving a community that is suffering severely from the current pandemic, with higher death rates due apparently to a high incidence of pre-existing conditions) and Mary Putnam Jacobi (1842-1906) (the first woman admitted to the medical school in Paris) were pioneering pediatricians–helping others. Yet medical knowledge was so limited in their lifetimes that they lost five of their own children at birth or shortly thereafter. They are interred together in section 61, lot 13850. An eye and ear specialist, Dr. Cornelius Rea Agnew (1830-1888) (section 161, lot 38342), was a leader of the United States Sanitary Commission, a private organization formed in June 1861, early in the Civil War, to improve health conditions for and provide medical care to citizen-soldiers, as well as assistance to their families.

Scientists have offered their training, knowledge, and willingness to risk themselves to help others. Dr. George Albert Soper (1870-1948) (section 105, lot 3468) was a sanitation engineer and epidemiologist who, in 1904, determined that Mary Mallon, widely known as “Typhoid Mary,” though asymptomatic, had infected many others with whom she had lived over a ten year period. Dr. William Hallock Park (1863-1939) (section 13, lot 9314), bacteriologist and laboratory director of the New York City Board of Health, Division of Pathology, Bacteriology, and Disinfection from 1894 to 1936, oversaw the development of a mass-produced antitoxin to treat diphtheria. Born in Cuba and an immigrant to the United States, Dr. Aristedes Agramonte (1868-1931) (section 187, lot 19370) was a physician, pathologist and bacteriologist whose specialty was tropical medicine. In 1898, the U.S. Army sent him to Cuba to study a yellow fever outbreak there. He worked with Walter Reed on yellow fever research and took part in the discovery that mosquitoes transmitted that deadly disease. He also devoted his life to the study of a host of other diseases, including plague, dengue, trachoma, malaria, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever.

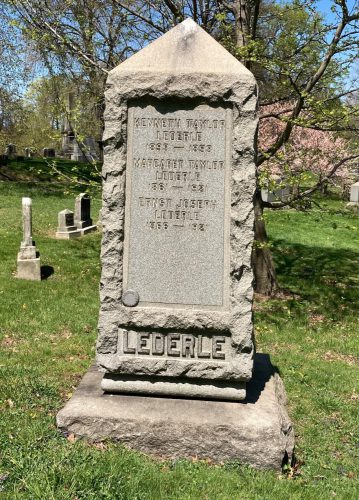

Ernst Lederle (1865-1921) (section 61, lot 13623) served as New York City Health Commissioner (1902-1904, 1910-1914), carrying out a mass small pox immunization program and fighting a typhoid fever epidemic. He then founded Lederle Labs, where the antibiotic aureomycin was created, as well as antitoxins and vaccines to fight epidemics. He preached that “[w]ithin natural limitations, a community can determine its own death rates.”

Elizabeth Gloucester (1817-1883) (section 31, lot 9817) was a remarkable African American woman. She was a self-made real estate tycoon, described in her Brooklyn Eagle obituary as the wealthiest woman of color in America. She used that wealth to support causes dear to her heart and her race: the work of Frederick Douglass, the Colored Orphan Asylum, the Siloam Church (her husband was its minister; she donated money for it to purchase land in what is now downtown Brooklyn and to build its church there) and John Brown (as he prepared for his ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, aimed at triggering a slave rebellion across the South to end slavery).

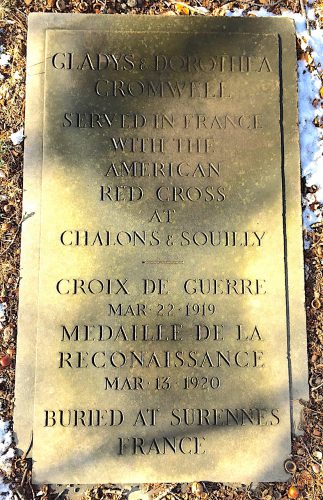

There are many selfless nurses interred at Green-Wood. Twins, Dorothea and Gladys Cromwell (1885-1919) (section 70, lot 1792), volunteered to serve in France during World War I, worked at the front lines, treated the wounded and sick, and perhaps as a result of “shell shock,” what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), killed themselves on their way back home.

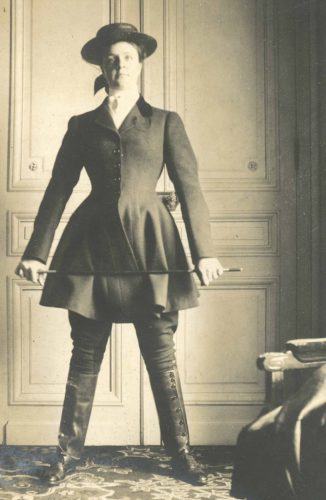

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Annie Rensselaer Tinker (1884-1924) (section 161, lot 27605) sailed to Europe and volunteered as a nurse for the British Red Cross. She provided treatment and comfort to soldiers on the front lines in Belgium, France and Italy. In 1921, the French government awarded her a medal for her relief work. She spent much of her life campaigning for women’s rights.

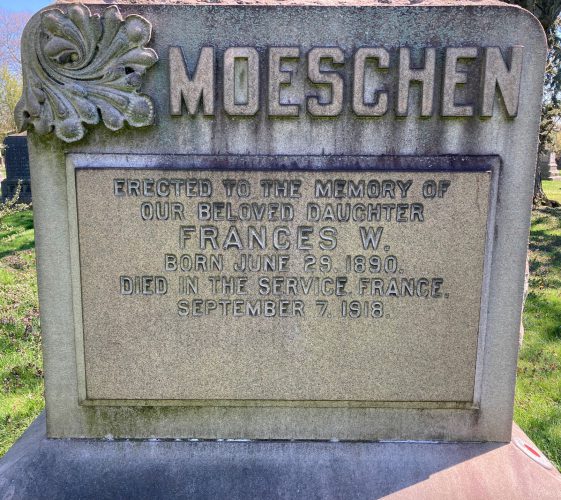

Laura O. McGrath (1889-1918) (section 147, lot 22297) was a graduate nurse at the Methodist Episcopal Hospital in Brooklyn when she was assigned, as a member of the Army Reserve Nurse Corps, to Camp Grant in Winnebago, Illinois, where the 86th Division was training for service in World War I. While fighting the influenza pandemic that was sweeping the camp and the country, she likely caught it herself and died there of pneumonia. A Red Cross nurse serving in France, Frances Moeschen (1893–1918) (section 138, lot 24881) also died of pneumonia as the 1918 Pandemic swept through France. She was just twenty-eight years old.

There were those who led because they saw a need that no one else was filling. During the Civil War, Ann Priscilla Vanderpoel (1814-1871) (section 74, lot 1785) helped found the Ladies Home U.S. Hospital on Lexington Avenue and 51st Street in Manhattan in April of 1862 to treat wounded and diseased soldiers. For her work, she was known as “The Florence Nightingale of New York.” On Decoration Day, 1876, a delegation of veterans of the Civil War, who remembered her dedication to them and their comrades, visited her grave and adorned it with an American flag.

Isaac T. Hopper (1771-1852) (section 31, lot 5805) was a Quaker who adopted many causes on behalf of others: abolition, prisoners’ rights, the indigent, escaped enslaved people, and more. It was said of him: “When pestilence was raging, he was devoted to the sick, and the poor were continually calling upon him to plead with importunate landlords and creditors.”

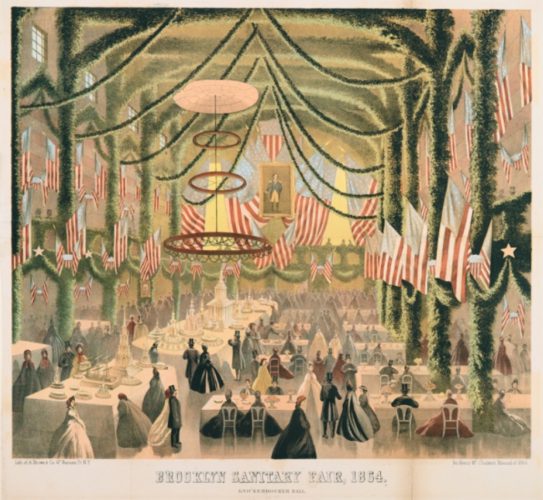

When it became apparent that the federal government did not have the wherewithal–neither to money nor the infrastructure–to take proper care of the health of Union soldiers during the Civil War, Marianne Stranahan (1812-1866) (section 81, lot 1826) stepped up to organize Brooklyn’s Sanitary Fair. Held in 1864, it raised money to fund the great work that the United States Sanitary Commission was doing to prevent disease and treat those who became sick or were wounded in battle. She reported that the fair had been a great success, raising half a million dollars for the cause–the equivalent of $8.2 million in 2020 money.

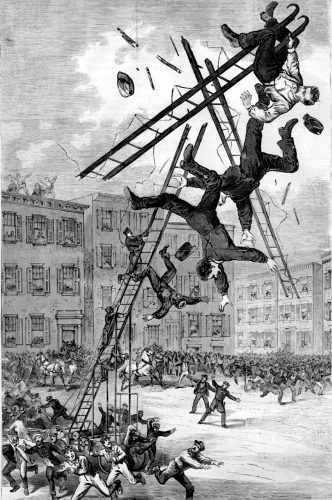

Many fireman who are interred at Green-Wood have demonstrated exceptional heroism. William Nash (1832-1875) (section 15, lot 17263, grave 1042) served with gallantry and bravery during the Civil War, leading his men in battle from the front as a captain of the elite United States Sharpshooters. He suffered the horrors of Confederate prisoner of war camps for a year, repeatedly escaping and being recaptured.

After the war, he joined the New York City Fire Department and quickly rose to battalion chief. He received the department’s highest award when, without the protection of a hose-line, he rescued two children from a fire. On September 14, 1875, he and his men were assigned to publicly demonstrate a poorly-constructed prototype of an aerial ladder. He once again took command, reassuring his men by demonstrating his own courage, leading them up the ladder. Tragically, when he reached the top, the ladder collapsed and he and two other firemen fell almost 100 feet to their deaths.

In 2017, two police officer who are interred at Green-Wood and died a century ago from injuries sustained in the line of duty were honored by the NYPD. Police Officer William Galbraith (1869-1911) (section 122, lot 17806, grave 347) was on mounted patrol in the Bronx in 1911 when he was thrown from his horse, suffering a skull fracture and a cerebral hemorrhage; he died six days later at Fordham Hospital at the age of 42, leaving behind a wife and two young children.

Police Officer Gustav Boettger (1883-1922) (section 85, lot 5995) was on mounted patrol in 1910 when he saw a runaway horse bolt down Fulton Street in Brooklyn. Boettger raced to catch up and grab the horse’s bridle. But, as he did so, a vehicle knocked the officer off his horse. Boettger was then dragged down the street and was struck by yet another vehicle, which fractured his skull. Undeterred, Boettger remounted his horse and, with the help of another officer, captured the runaway. Boettger was close to death for six months, but eventually returned to the job. In 1922, eleven years later, and just 39 years old, he died of cardiac arrest, likely as a result of his injuries while doing his job, protecting citizens.

On 9/11, Steven Vincent (1955-2005) (section 73, lot 44939) was living in the East Village, working as an art critic. After the attacks that day on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, he left everything and went to Iraq to report the real story of what was going on there. On July 31, 2005, his op-ed piece, “Switched Off In Basra,” appeared in The New York Times. In it, Steven reported on the dominance of religion-based militias in Basra, and “. . . that there is even a sort of ‘death car’: a white Toyota Mark II that glides through the city streets, carrying off-duty police officers in the pay of extremist religious groups to their next assignment.” Two days later, on August 2, Steven and his interpreter were kidnapped on the street by four or five men, dressed in police uniforms, driving a white car. Both Steven and the interpreter were shot several times; Steven died that night, but the interpreter survived.

With $3,000 hidden on his body, Varian Fry (1907-1967) (section 11, lot 28208) flew to Marseilles in August, 1940, to begin one of the least known, but most heroic actions of the twentieth century. By the time he returned to New York a little over a year later, Fry had saved 2,000 souls, some famous–including Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, and Hannah Arendt–and some little known–from Nazi slaughter. For his selfless work, Fry was honored as a Righteous Among Nations at Yad Vashim in Israel, the first American to be so recognized. In 2017, 50 years after his death, Green-Wood organized a commemoration and symposium in honor of this great man.

This notice was printed upon Sgt. Manny Hornedo‘s (1978-2005) (section 96, lot 44905) death:

Family, uniformed comrades, and a color guard gathered at the grave of Manny Hornedo of Sunset Park on July 2 to remember him. Hornedo enlisted in the National Guard soon after 9/11 in 2001. He was working at The Gap store in Herald Square in January, 2005, and had passed the test to become a court officer, when his unit, the 1569th Transportation Company, was activated and sent to Iraq. In June of 2005 he was manning a machine gun, protecting a convoy near Tikrit, when a truck explosion killed him. He is survived by his wife and high school sweetheart, Melissa, and two young children, Manny, Jr., and Marcus.

And thousands of others.

* * *

While we are paying tribute to heroes, let us remember Green-Wood’s staff, who for 180 years has been interring the dead–through the Pandemic of 1918, yellow fever and cholera outbreaks, disasters, and more– regardless of the danger to themselves in doing so. That tradition has continued with today’s gravediggers and crematory operators who, risking their health and their lives, have kept the cemetery operating, albeit at tremendous strain due to burial and cremation rates two and three times that of a pre-pandemic period. Just being heroes and doing their jobs. Here’s a recent profile of one such hero–Gus Padilla–a Green-Wood worker who was detailed from his regular job of restoring monuments and mausoleums to work in the crematory. And here’s another of Ali Meawad, who has also been reassigned to work long days in Green-Wood’s crematory. Those staff who volunteered to work in the Green-Wood office, answering phones, making arrangements for all too many funerals and cremations–they too are heroes.

* * *

Stephanie Carey is a public health official who has been a Green-Wood Volunteer for 18 years. . She “discovered,” interred at Green-Wood, the public health officials who are discussed above. Not surprisingly, Stephanie has long been fascinated by the Pandemic of 1918 and Green-Wood’s records of burials resulting from it. She wrote to me recently:

I’ve spent the better part of 30 years in Public Health. Public health at its best is all about preventing bad things from happening. A century ago, C. E-A Winslow, a pioneer in the field,, said, “If we had but the gift of second sight, only then would we know the silent victories of Public Health.”

My team has drilled for years to be prepared for hurricanes, terror attacks…and for what a pandemic would look like. I’ve taught about the ravages of the 1918 Spanish Influenza. But I never expected to experience the real thing.

My team first gathered to launch preparations for this pandemic in January. Even then, the virus seemed far away, just another drill. When we next gathered, a couple of weeks later, the room was grim. This was not a drill.

Some have likened this pandemic to a war. We have the warriors on the front line, those who staff the hospitals. We have logistics, and we have those on the home front, making sacrifices to support the war effort.

As the disease approached, my team worked to identify and quarantine those who may have been infected. It was a holding action, to buy hospitals precious time to prepare for the life and death battle. We struggled to find testing for those who may have been infected. We worked with businesses and faith groups and schools to try to figure out how to serve our clients, congregants, and students safely. We had to convince the entire population to stay home, to disrupt their lives to an extent not seen in living memory. We counteracted fear and disinformation with a steady stream of honest facts and empathy. We struggled along with emergency managers to try to find masks and safety equipment for health care workers and EMS. We try to provide clear, understandable guidance, when the guidance is changing almost every day. We try to interpret a fire hose of data, and try to have it make sense to a population that is understandably anxious and scared.

And for life to approach some semblance of normal, the front line then becomes the public health contact tracer. We are mobilizing to pull together that army, at a level not seen in living memory. For everyone else to get back to work, we have to isolate the sick and quarantine those who may have been exposed. Then, we can use the summer to recharge and restock. Because in 1918, the spring wave was followed by a brutal wave in the fall.

I’m exhausted. I haven’t had a full day off in almost 2 months. I can only imagine how the hospital workers feel.

I am heartened by what people are doing to help— buying groceries for neighbors, encouraging each other by phone and video, sewing masks for grocery store workers and elderly neighbors.

If we pull together we will get though this.

* * *

And thanks to volunteer Ken McKenzie, who took many of the gravestone photographs above.