My most recent book, “The Gallant Sims”: A Civil War Hero Rediscovered, was published by The Green-Wood Historic Fund in 2016. It is the story of Samuel Harris Sims, a brave and noble man, who in 1861 left his work as a glass stainer in Brooklyn to fight to preserve the Union during the Civil War. Early in that war, he recruited a company of 100 men, many of whom were his Brooklyn friends and neighbors, to serve as Company G of the 51st New York Volunteer Infantry. As the war went on and on, he refused all promotions and transfers, preferring to stay loyal to his men. In July, 1864, he was killed in battle. His comrades, who loved him dearly, called him “The Gallant Sims.”

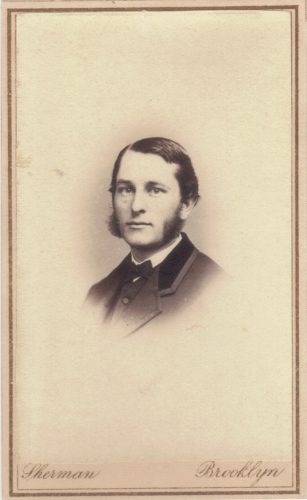

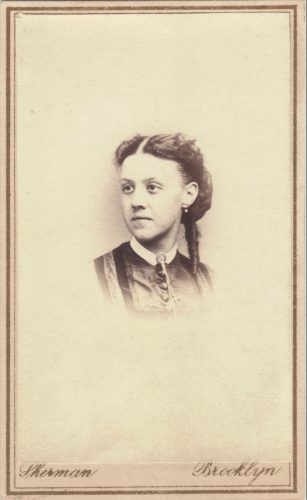

When I was in the final stages of getting that book ready for publication, two photographs surfaced, courtesy of Greg Di Salvio, a longtime collector and Civil War re-enactor, who had purchased them back in 1997. One was of Captain Sims, perhaps a few years before the Civil War began in 1861, the other likely of his wife Mary Ann.

I detailed that find of the above two photographs almost four years ago in this blog post. In the book I made an educated guess that these photographs likely dated from 1860. However, I now think, based on how young Samuel Sims looks here, that they might have been taken a bit earlier: perhaps in 1858 or 1859.

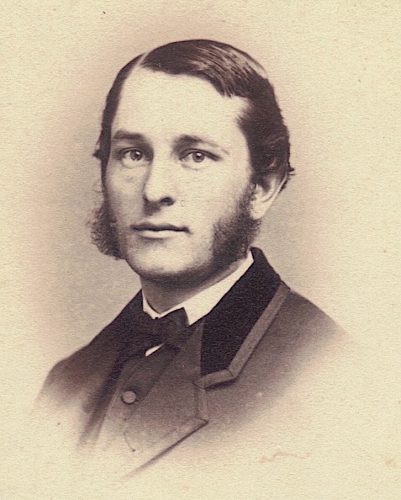

That thesis is supported by a comparison of these two photographs:

To my eye, Samuel Sims, in the photograph at left, looks several years younger than he does in the photograph at right–perhaps as many as five years younger. So, if the photograph at right dates from 1863, then the photograph at left might be from around 1858.

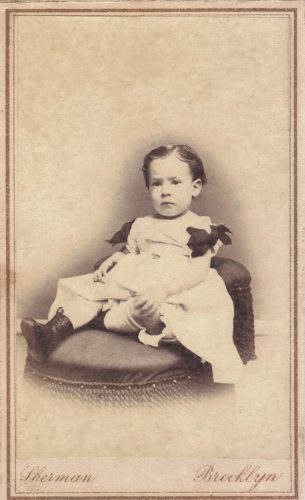

And now this photograph below has surfaced, spotted by the same collector, Greg Di Salvio:

Greg Di Salvio is a collector of many things–primarily from the 19th century. He often goes hunting through second-hand stores in Brooklyn and elsewhere, looking for something that catches his eye. A few weeks ago, he was combing through a box of photographs in one such store, when he came across the above photograph, flipped it over, and recognized the name written in pencil on its back, “Lucy Hale Sims”–which just happens to be the name of Captain Sims’s and Mary Ann Sims’s only daughter.

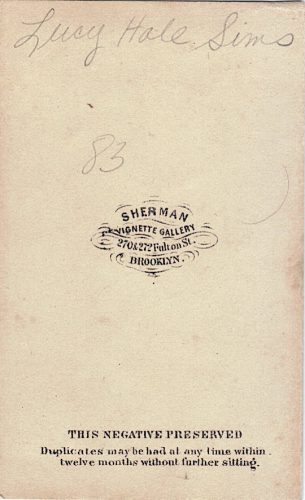

It is a fundamental rule of interpreting the story of an antique–whether a 19th century photograph or a 16th century painting or an 18th century piece of furniture–that what appears on the back of the item is often a treasure trove of information and key to understanding it. The back of the carte de visite photograph (commonly referred to as a cdv) of the young girl above is particularly interesting:

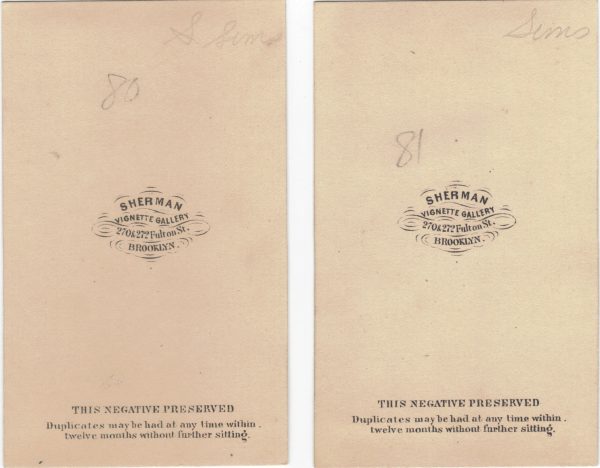

Two notations appear in pencil on this back: a name and a number. They are both significant. The name is “Lucy Hale Sims” and the number is “83.” Though this matter is admittedly subjective, the script handwriting does look to me like it was written in the 19th century. It is very typical of a practice that makes great sense–writing the name of the subject of a photograph on its back-but a practice that is not quite as universal as it should be. Not surprisingly, the market for a photograph of an identified subject is much more vigorous than that for a similar photograph whose subject is unidentified. And the number “83” is particularly significant when we look at the backs of the images of Captain Sims at left, and what I believe to be his wife, Mary Ann Sims, at right:

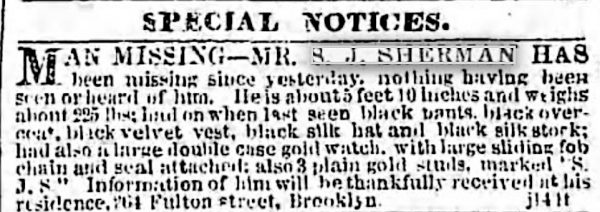

Note also that the script handwriting of “Sims” at the top of each of these three backs appears to be by the same writer. Further, the numbers are significant for how close they are to a sequence–“80” on the back of the photograph of Samuel Sims, “81” on the back of the photograph of his wife, and “83” on the back of the image identified as “Lucy Hale Sims”–the name of their daughter. These penciled numbers are likely inventory numbers of the photographer Sherman. He is listed in Brooklyn’s city directory of 1865 as “S.J. Sherman,” a photographer working at 270 Fulton Street and living at 264 Fulton Street. It appears that Sherman himself served during the Civil War; a “S.J. Sherman” served with the 7th New York Infantry in the earliest days of that conflict, April-May, 1861.

Just as an aside that I could not resist, while researching S.J. Sherman I came across this unusual notice in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of January 14, 1861, which offers a a detailed description of our photographer:

Note the text at the bottom of the back of each cdv: “THIS NEGATIVE PRESERVED/Duplicates may be had at any time within twelve months without further sitting.” Clever advertising! Sherman, the photographer, had done the bulk of his work at the “sitting;” he hoped to make more money selling extra copies, but put a twelve month window on such sales, ostensibly to give his customers some sense of urgency to order now. In any event, the fact that these numbers are so close to each other–80, 81, and 83–would seem to indicate that the photographs are related and all were taken at the same sitting.

Further, the printed text and layouts of the fronts and backs of these photographs, identifying Sherman at 270 & 272 Fulton Street in Brooklyn as the photographer/publisher, are identical (a photographer’s addresses and designs would change over time), indicating that they were from the same era and raising the distinct possibility that all three were the product of a single photographic session.

So who was Lucy Hale Sims? Daughter of Samuel and Mary Ann Sims, she was born in Brooklyn in 1853. In my book I concluded that the first two photographs above–those of Lucy’s parents–were taken about 1860. This makes sense because the carte de visite, a photograph mounted on thin cardboard about the size of a business card, was first introduced in France in 1854; by 1859 it had gained great popularity across America. However, this image might be a bit earlier than 1860, particularly because Brooklyn was a hotbed of photographers in this era, and they were likely to be early adopters of this latest photographic craze. Given that Lucy was born in 1853, she appears in this photograph as the appropriate age for the photograph to date from 1858 or so.

Lucy’s mother, Mary Ann Sims, died in December of 1860 of anemia. When Captain Sims died in 1864, he left three children orphaned. Soon after his death, Lucy, the only Sims daughter, was adopted as the “Daughter of the Regiment” by veterans of the 13th New York State Militia. Captain Sims had served in that regiment for years, both before and during the Civil War, and he had many friends and admirers who had served with him in that unit. Here are excerpts from my book that tell this story of Captain Sim’s comrades and their adoption of his orphaned daughter:

As “C.D.B.” reported in a letter to a Brooklyn newspaper in 1888, the 13th Regiment had adopted Lucy soon after her father’s death, making her the “Daughter of the Regiment:”

The members of the Thirteenth Regiment have not been content, however, with hallowing the memory of Captain Sims. They made a practical application of their regard by adopting his daughter, making her the daughter of the regiment, subscribing to a fund and expending it in her education. She was sent to Vassar College, and is now a teacher in one of our public schools.

James de Mandeville, in his History of the 13th Regiment, N.G., S.N.Y (which abbreviates National Guard, State of New York), gave further details:

MISS LUCY H. SIMS, THE DAUGHTER OF THE THIRTEENTH.

AMONG the many interesting episodes connected with the history of the Thirteenth there was one in particular, embodying combined qualities of pathos and romance, that testified to the manly traits that are predominant characteristics of the regiment. Captain Samuel H. Sims of Company G, Fifty-first Regiment, New York Volunteers, formerly a Second Lieutenant in Company B, Thirteenth Regiment, was killed at the explosion of the mine at Petersburg, Virginia. Captain Sims left a motherless daughter about fifteen years of age, named Lucy, whom the regiment enthusiastically determined to adopt and care for during her minority. Accordingly, in January 1866, General John B. Woodward, then the Colonel of the Thirteenth, formally introduced Miss Lucy H. Sims to the regiment in the Armory at Flatbush Avenue and Hanson Place, and she was adopted by the command as the Daughter of the Regiment. Each member of the organization was assessed a small sum for her support, and a committee was appointed to provide for her welfare and to supervise her education. Miss Lucy was educated at the expense of the Thirteenth at Vassar College, and after her graduation became a successful teacher in the Washington Avenue School, No. 11. During the four years that she had been the ward of the regiment upwards of $6,000 was contributed by its members for her maintenance. The committee who had the management of her affairs was composed of Colonel Woodward, Captain R. V. W. Thorn and Captain F. A. Baldwin.

The assessment for Lucy’s education and welfare was $1 per annum for each veteran. A committee was established to carry out the details, and a veteran designated to be her “father.” Lucy attended preparatory school, studied at Vassar College to be a teacher, and graduated with honors. She taught for many years at P.S. 11 in Brooklyn. She never married.

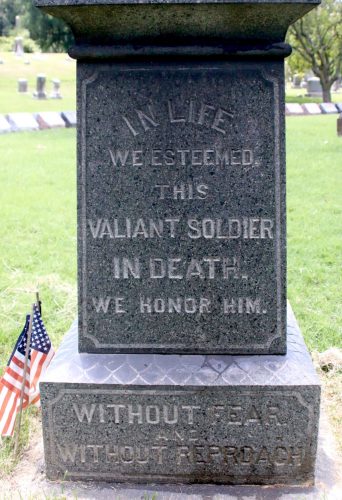

Though Captain Sims’s body was interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in 1864, his story–and his daughter Lucy’s involvement in it–was far from over. One day in 1886, one of Captain Sims’s Civil War comrades, who had served with “The Gallant Sims” during the Civil War, came across Sims’s unmarked grave at Green-Wood Cemetery. Convinced that the beloved captain deserved better, he began a campaign to raise money for an appropriate memorial. On September 17, 1888, this monument was unveiled in Cedar Dell in tribute:

This left side of the memorial to Captain Sims, as shown in this photograph, puts into words the love and respect his comrades had for him:

Lucy Hale Sims was an honored guest at the unveiling of the gray granite monument to her father. The back of the base of this memorial was reserved for her–though no one could have anticipated it would be inscribed so soon thereafter. Sadly, on April 19, 1889—just seven months after the dedication of her father’s monument at Green-Wood, Lucy Hale Sims, the only daughter of Samuel and Mary Ann Sims, died from tuberculosis at her home at 1311 Dean Street in Brooklyn. Still a young woman of only 36 years, just two years older than her father had been when he was killed in battle, she was buried alongside him, between dogwood and cedar trees, in a grave dug at the base of the Sims Monument. The back of the Sims Monument was inscribed in her memory:

This is for you Jeff Richman you did Justice to Lucy Hale Sims Story and the Sims Family in your Blog

Looking forward to Mr. DeSalvio’s discovery of photo #82…!

The details of Mrs. Sims’ death from “Anemia” lead me to wonder if what she died from was actually Pernicious Anemia, a condition that was fatal and from which a woman would have died in her early adulthood. Causing an inability to manufacture the cells needed to produce Vitamin B12, it led to multiple still-births, further weakening the lady. It is, also, a genetic condition, inherited. My father’s mother died of this condition in the 1930s, shortly after the discovery of the Intrinsic Factor. Today, persons do not die of this affliction, they are administered shots of Vitamin B12, usually monthly. Often called a ‘wasting away’ disease.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge on this. Very interesting.