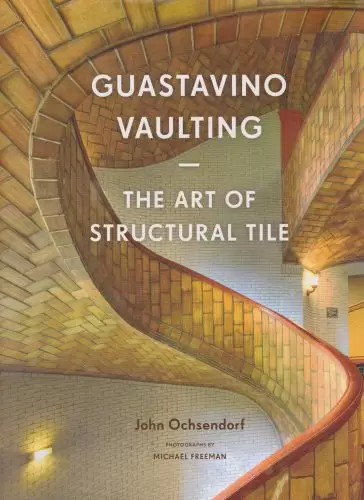

In 2014, the Museum of the City of New York (MCNY) mounted an exhibition, “”Palaces for the People: Guastavino and the Art of Structural Tile.” A wonderful public display, one of the best of the many museum exhibitions I have attended over the years, it told the story of Spanish immigrant Rafael Guastavino, Sr, his son and namesake, and their family enterprise which played a unique and central role in the building of New York City a century ago. That company did the spectacular structural tile work for a generation of more than 200 of the best buildings in New York City that were designed by NYC’s leading architects–including ceilings of the Registry Hall on Ellis Island, the Oyster Bar in Grand Central Terminal, the Elephant House at the Bronx Zoo, and Carnegie Hall. The MCNY exhibition was originated by Professor John Ochsendorf, who teaches structural engineering at M.I.T. and was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, or “Genius Grant,” in 2008. John, who also describes himself as an architectural preservationist, co-curated the 2014 exhibition at MCNY and literally wrote the book on this subject: Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tiles.

Here’s a fine example of Guastavino tile work:

Early in 2014, in the months just before the MCNY exhibition opened, its curators sent a team out to Green-Wood to capture videos of four Guastavino ceilings there: two private mausolea, the Ninth Avenue Entrance Gates (at the doorways to either side of the entrance road), and the Historic Chapel. When they arrived, I guided them to each of the first three. However, with respect to the Historic Chapel, I assured them that, as Green-Wood’s historian, I knew that there were no Guastavino tiles in that building. I had never seen any such thing!

Fast forward to a few months ago. I was working with Julie Sloan, who supervised the recent restoration work on the stained glass windows in Green-Wood’s Historic Chapel, and we were reviewing her slide show for an upcoming Zoom conversation we had scheduled about that work. As we went through her photographs, this image appeared on our shared screens:

Though I have been in the Historic Chapel hundreds of times, I had never seen these tiles before–because they are hidden from public view. Rather, this is the only view I had ever seen of the Chapel’s chandelier and skylight–and it was from below them:

I had one question for Julie when I saw the image of the tiles: “Is that Guastavino tile?” Julie, who is one of the leading experts in American stained glass, demurred, saying that that was not in any way her area of expertise; she did not know. But she offered to ask the consulting architect on the Historic Chapel restoration project. His response, as relayed by her soon thereafter: they were just “glazed tiles.”

I thought about that response for a few days, then decided that the Internet might be my friend on this. So I searched for “guastavino” and “greenwood” (the typical misspelling one finds of “green-wood”)–and here is the catalogue entry that popped up from the Columbia University Libraries:

Note that this entry, a part of the archives of the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company which was donated to Columbia in 1963, is for a “detail drawing of vault” of the Green-Wood Cemetery Chapel. The catalogue description further notes that there is a notation on the drawing: “Approved by architects. Jul 27 1911–stamped in ink next to title block.” That was quite a find! It seemed to confirm my suspicions.

I found that date of approval–July 27, 1911–to be particularly important. It was of course possible, as one person with whom I excitedly discussed my discovery suggested, that the architects, Warren & Wetmore, had in fact approved the plans for the installation of Guastavino tiles, but that as time went by, those plans had changed. Perhaps the use of Guastavino tiles had been approved by the architects but then a decision had been made to close them off from public view with the chandelier and skylight, and the decision was then made by the architects and/or cemetery trustees to change to less expensive tiles. So I took a look at this photograph of the Historic Chapel, taken as it was being built:

Note the date at the bottom center of the image: July 6th 1911. Above the doorway, in which two workers stand, the rebar for the dome of the building is visible, already in place. This tells me that the tile installation in the dome was not far off–and, given that the use of Guastavino tiles had been approved by the architects exactly three weeks later, any time to shift plans, and abandon the agreement with the Gaustavino Company to supply the tiles for the Historic Chapel’s dome, was very limited.

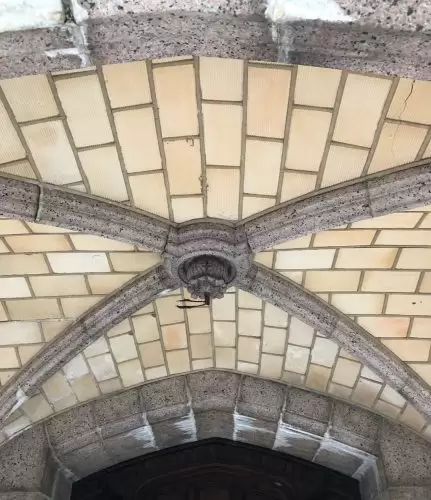

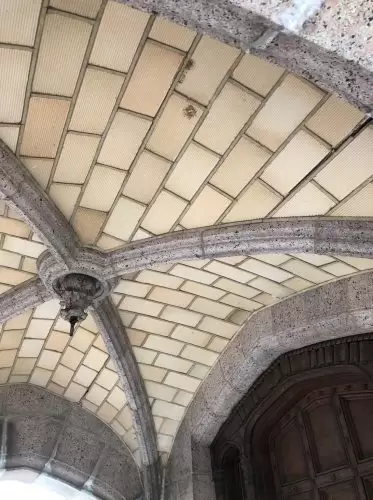

My next move was to contact the expert on Guastavino: Professor John Ochsendorf. I managed to find contact information for him, called and left a voicemail, then emailed him, describing what had happened and adding these other photographs of the tiles in the Historic Chapel’s dome that Julie had sent me:

Soon after I sent these images off to John, we were on the phone talking excitedly–and he was unequivocal: not only did the plan at Columbia document that the tiles in the dome of the Historic Chapel were Guastavino, but his eye, even if those plans were unknown, told him that there was no doubt that both these tiles and their manner of installation required one conclusion: Guastavino. John was particularly thrilled because, as he explained, this put Green-Wood Cemetery in the midst of a crucial period of Guastavino work, in collaboration with the very prominent architectural firm of Warren & Wetmore. In rapid succession, Guastavino had installed its tiles in three buildings designed by that firm, all of which have since been designated New York City landmarks: the magnificent lobby of the Vanderbilt Hotel, the Oyster Bar of Grand Central Terminal, and in the dome of Green-Wood’s Historic Chapel. As John later wrote to explain,

This is a crucial period in the close collaboration between Rafael Guastavino Jr. (1872-1950) and the architects Warren & Wetmore, and it is very exciting to discover that this work of Guastavino tile vaulting is still in existence at Green-Wood. In particular, this collaboration led directly to concerns about dampening the noise reverberation in Guastavino spaces, which then lead to a new chapter in the company’s work relating to acoustical tile materials in the coming years. But above all, an exciting new frontier in the history of Guastavino architecture is to study collaboration with specific firms such as Warren & Wetmore. So this is another puzzle piece in our efforts to understand the develop, dissemination, and preservation of Guastavino vaulting.

It should be noted that these three spectacular collaborations between Warren & Wetmore and Guastavino opened in just over a one-year period: the Vanderbilt Hotel in January of 1912, Grand Central Terminal in February, 1913, and Green-Wood’s chapel in mid-1913. Further, as both John and I knew, this connection between architects and tile maker was further extended Warren & Wetmore by their collaboration on Green-Wood’s Ninth Avenue Entrance in 1925–with the Guastavino tiles in the ceilings of the entryways.

This placed Green-Wood–and the work there by architects Warren & Wetmore, in collaboration with Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company, at the center of this important partnership.

Professor Ochsendorf further noted, “It seems possible that the ceilings below the skylight are also Guastavino and that they were treated/painted/stuccoed when the skylight was added.”

So, there you have it. A discovery of a hidden element of Green-Wood’s Historic Chapel, known by those who planned and built it more than a century ago, but long forgotten, had now been found. And, an expert tells us, this is an important story of early 20th century architecture in New York City–a story in which Green-Wood played a central role. Quite thrilling!

What a wonderful find! I enjoyed reading this so much and plan on visiting Greenwood again next time I am in New York. I have many ancestors buried there but I have never visited the chapel.

Yes, do come visit. The Historic Chapel has undergone a thorough restoration, inside and out. It is looking great!

Just another one of the many, many interesting finds in this remarkable cemetery. When I was there for two days in September, I could not get into the Chapel. Big regrets. Thanks.