In 2002, after Green-Wood restored and rededicated New York City’s Civil War Soldiers’ Monument, we launched Green-Wood’s Civil War Project. Its aim was to identify as many Civil War veterans as possible, to write a biography for each, and to mark, with gravestones obtained from the Department of Veterans Affairs, the graves of those that were unmarked. That project has had success beyond our wildest dreams. Our expectation, when it started, was that we might find up to 500 Civil War veterans interred at Green-Wood. But, through the efforts of hundreds of volunteers, we have found approximately 5,200–and each now has an online biography. We have also marked more than 2,000 formerly-unmarked graves.

But one of the frustrations of our Civil War Project has been our inability to identify men of color who fought for the Union as well as emancipation–and are interred at Green-Wood. Despite our best efforts, going through the rosters of regiments of “Colored Troops” (as they were known during the war; the United States created the Bureau of Colored Troops in 1863) that were recruited in New York City or Brooklyn, we have only identified one African American–John Munroe–who served in the Civil War. That, though, may be changing, as a result of happenstance and recent research.

One of the difficulties of the searches that we did of these “Colored Regiments” was the commonality of names among soldiers of color. Another is the very limited historical records–rarely having much more than a name–that have survived. And this research is made all the more difficult by the fact that Green-Wood, in recording burials, did not record the race of the individual being interred.

So now let’s pull back for some background on African Americans who served in the Civil War. As the National Archives reports on its website:

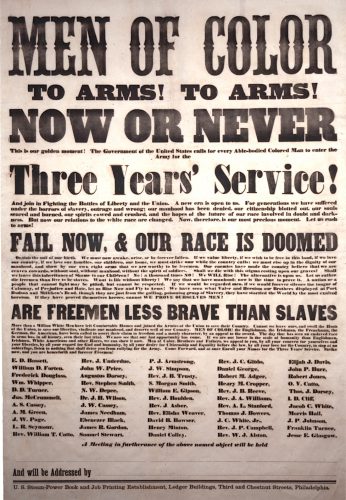

The issues of emancipation and military service were intertwined from the onset of the Civil War. News from Fort Sumter set off a rush by free Black men to enlist in U.S. military units. They were turned away, however, because a Federal law dating from 1792 barred Negroes from bearing arms for the U.S. army (although they had served in the American Revolution and in the War of 1812). In Boston, disappointed would-be volunteers met and passed a resolution requesting that the Government modify its laws to permit their enlistment.

Noah Andre Trudeau writes in his Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War, 1862-1865, that at the outset of the Civil War the men of color who met in Boston, at the Twelfth Baptist Church, resolved that they were “ready to stand by and defend the Government with ‘our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.'” In Philadelphia, Providence, New York, Cincinnati, and elsewhere, Black militia units began to form to join the fight. The services of “300 reliable colored free citizens” were offered to protect Washington, D.C., from Confederate attack. Nicholas Biddle, a 65-year-old Black man from Pottsville, Pennsylvania, put himself into the ranks of a local artillery company and joined their march to Washington. When that unit marched through Baltimore in 1861, it, like other Northern militia regiments, was attacked by a secessionist mob; Biddle was hit in the face and bloodied by a stone, but continued with his new comrades to defend the nation’s capital. But, it should be noted, it appears that Biddle did not enlist; rather, he joined the march of a militia unit.

Trudeau continues:

Hardly had the initial heady enthusiasm settled down, though, before state and Federal governments proclaimed a war policy that pointedly excluded African Americans. Washington’s National Intelligencer explained on October 8, 1861, ‘”The existing war has no direct relation to slavery. It is a war for the restoration of the Union under the existing Constitution.”

The United States Secretary of War responded to that offer of “300 reliable colored free citizens” to defend Washington with this: “I have to say that this Department has no intention to call into the service of the Government any colored soldiers.” Newly-formed Black militia units were ordered to disband, under threat of arrest as “disorderly gatherings.”

It would not be until President Abraham Lincoln’s controversial issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, that men of color were lawfully authorized to serve in the Union armies. And, their service would be limited to that in Colored Regiments–regiments of Black men, led by white officers (with but a very few exceptions). In all, approximately 180,000 men of color served in the Union armies and navies during the Civil War, according to the Library of Congress.

So, it came as quite a surprise to me when I began to suspect that two men who are interred at Green-Wood, whom we thought we had identified as having served in what have been assumed to have been all-white regiments during the Civil War, may in fact have been men of color who were interred in unmarked graves in Green-Wood’s Freedom Lots. We believed that those lots, which were in Green-Wood’s archival documents referred to, and known historically, as the “Colored Lots,” and are now known as the Freedom Lots, presumably have only African Americans interred there (with the exception of one white matron who worked at the Colored Orphan Asylum, which owned one of the seven lots that together make up the Freedom Lots). Working closely with me, Jim Lambert, a volunteer, recently combed through Green-Wood’s burial ledgers for the Freedom Lots, line by line, and determined that some 1,330 people ––presumably all of color except one ––are interred in them. Yet, the soldier histories that I had matched to these two men were for soldiers who had served in what were ostensibly “white-only” regiments. Was I correct when I concluded that these two men, interred in the Freedom Lots, were men of color who were barred by law from serving in all-white regiments–but had in fact served in those units? Had I made a fascinating discovery– that in fact some men of color had served in what were assumed to have been all-white regiments during the Civil War?

During the Civil War, a recruiting officer had nothing, other than his observations, to check the race of a man who presented himself for enlistment. The officer’s primary focus was to sign up enough men to form a company of 100 men or even a regiment of 1000 men by a rapidly-approaching deadline. How was this hard-pressed officer to verify the identity of the person before him–and that person’s race? No fingerprints. No social security number. No photo ID. We do know that, while estimates vary, approximately 400 women walked individually into recruiting offices, disguised as a man, identified themselves with a man’s name, and enlisted in what were certainly supposed to have been all-male regiments. That figure of 400 comes from Mary Livermore, who worked for the United States Sanitary Commission during the Civil War. She wrote in her 1888 memoir: “Some one has stated the number of women soldiers known to the service as little less than four hundred. I cannot vouch for the correctness of this estimate, but I am convinced that a larger number of women disguised themselves and enlisted in the service.”

Co-authors Deanne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook write in They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the Civil War, that they have identified about 250 women who served in the armed forces of either the Union or the Confederacy. They cite “martial passions” as reasons why women, like men, would have wanted to serve in the war. Civil War historian James M. McPherson, in What They Fought For, 1861-1865, wrote that soldiers volunteered to serve in the Civil War because of ” . . . peer pressure; group cohesion, male bonding; ideals of manhood and masculinity; concepts of duty, honor, and courage; functions of leadership, discipline, and coercion; and the role of religion as well as of the darker passions of hatred and vengeance.” Others undoubtedly enlisted for the pay. And, men of color also would have been motivated to fight to free fellow members of their race–and even to prevent their own enslavement or the enslavement of family, friends, and community members–under the harsh provisions of the Fugitive Slave Law or during Confederate invasions of the North, as happened in Pennsylvania during late June and early July, 1863. Given this, is it difficult to believe that men of color, who would have identified themselves as such in other circumstances, having been frustrated with the bar to their fighting for the Union, might have enlisted in what were presumably all-white regiments?

As per Blanton and Cook, it was not hard for a woman to enlist:

Enlisting was quite easy. All a woman needed to do was cut her hair short, don male clothing, pick an alias, and find the nearest recruiter, regiment, or army camp. In the mid-nineteenth century individuals did not carry personal identification. Indeed, most people did not even have a birth certificate. Both men and women were free to become anyone they wished to be by simply moving to a place where no one knew them and creating a new persona. Army recruiters in the North and South usually accepted whatever information the recruit provided as to name, age, and former occupation.

What of physical examinations of those who wanted to enlist? Wouldn’t those screen women and perhaps men of color, preventing them from enlisting? As Blanton and Cook state in their book, mandates for those examinations were more often ignored than honored: “The pressure to quickly fill regimental ranks militated against finding reasons to deny a person’s proffered enlistment.” They continue: “For the most part, recruiters and surgeons only looked for a reasonable height, a least a partial set of teeth with which to tear open powder cartridges, and the presence of a trigger finger. All but the obviously deaf, blind, and lame were accepted into the service.”

Of course, if it was possible for hundreds of women to enlist, would it have been possible for an African American to do so, passing himself off as a dark-skinned white man? Trudeau reports that a Black man, William Henry Johnson, served with the 8th Connecticut Infantry at the Battle of First Bull Run in 1861 and at Roanoke Island in 1862. Johnson’s account of that battle appeared in the Pine and Palm, Boston’s Black newspaper. With respect to the question of whether Blacks should be armed to fight in the Civil War, Johnson wrote, “Shall we do it? Not until our rights as men are acknowledged by the government in good faith.” But fight Johnson did, in what was otherwise thought to have been an all-white regiment.

Years ago, I determined, based on a match between the name and likely year of birth of one Samuel Mann, who is interred at Green-Wood, to that of a soldier of the same name and a close year of birth, that the man interred at Green-Wood was a Civil War veteran. So, under my supervision, a volunteer wrote a biography for Samuel Mann and we applied for a gravestone from the Department of Veterans Affairs to mark Mann’s unmarked grave. However, it was not until that gravestone was installed, and I realized that it had been installed in the Freedom Lots, that I thought that perhaps I had made a mistake.

When I was out in the Freedom Lots a while ago, where the above gravestone had been installed, I noticed the regiment on the gravestone: 132nd New York. I realized that there was a problem: all men in the Freedom Lots are presumably Black. If the Samuel Mann interred there was Black, was it possible that he had served in the 132nd New York Infantry, a presumably all-white regiment? My initial reaction, upon seeing this gravestone in the Freedom Lots, was that that I had been mistaken in concluding that the Samuel Mann in the Freedom Lots had served in the 132nd New York Infantry. Therefore, it seemed, we had to remove and destroy this marker. But, before we did so, I wanted to be sure.

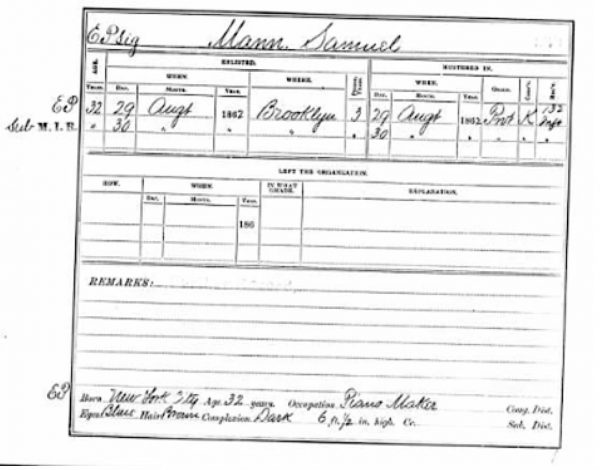

So I did some further research. This is the relevant soldier history for the Samuel Mann who served in the 132nd New York Infantry:

Residence was not listed; 32 years old.

Enlisted on 8/29/1862, at Brooklyn, N.Y., as a private

On 8/30/1862, he mustered into Company K, 132nd New York Infantry

(date and method of discharge not given)

(No further record)

In that same grave is Sarah Mann, whose last residence, according to Green-Wood’s records, was 431 West 18th Street in Manhattan. She was 55 years old when she died on June 4, 1880, of a defect in her heart valve, and was interred two days later. I searched online for other records pertaining to her, but found nothing.

Getting a match for a Civil War soldier and a man interred at Green-Wood is part art and part science. There is no magic formula. Sometimes the match is convincing: an obituary identifies the individual as a Civil War veteran and names his regiment. Sometimes pension index cards –several sets of which are available online–give a date of death for the veteran or his wife’s name that can be matched to other records. But sometimes it is more subjective. Here, I had nothing definitive. So I checked the frequency of the name Samuel Mann in an online Civil War database and discovered that thirty-seven men of that name served in the Union Armies of more than two million. But I also discovered that only two men named Samuel Mann had enlisted from New York State: one from Brooklyn and one from Plattsburg. So that is just two men out of close to 465,000 who enlisted from New York State–therefore a rare name for New York State enlistments. Further, the man who is interred at Green-Wood died late in 1868–when he was 37 years old–meaning that he likely was born in 1831. The soldier named Samuel Mann who enlisted at Brooklyn late in 1862 at the age of 32, based on the math, was likely born in 1830. That’s close to the year of birth for the Samuel Mann interred in the Freedom Lots.

Doing further research on Samuel Mann, the soldier who served in the 132nd New York Infantry, I discovered that, on his muster roll, his complexion is listed as “dark.”

That was intriguing!

Was it possible, during the Civil War, for a man of color to pass himself off as white in order to enlist and get steady pay while fighting for emancipation of his race, a cause he believed in? I have never read of such of thing–nor have the several Civil War experts I consulted on this–but it seems plausible, particularly in a time when there were virtually no records available to an enlistment officer indicating or verifying the potential enlistee’s race.

Accounts of Black men and women passing as white, dating back to the Civil War and before, are well documented. Allison Hobbs’s 2014 book, A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life, is an excellent recent example. Independent scholar Robert Fikes Jr. wrote in 2014 for the African American history website, Blackpast, on the centuries-old process in the United States of African Americans with no visible African ancestry “passing” into the Caucasian race or other races to avoid the stigma associated with anti-Black racial discrimination and social marginalization. He cites many works of nonfiction and fiction, including The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912) by Green-Wood permanent resident James Weldon Johnson.

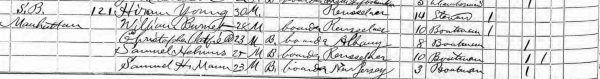

In doing further research on Samuel Mann, I found this census record:

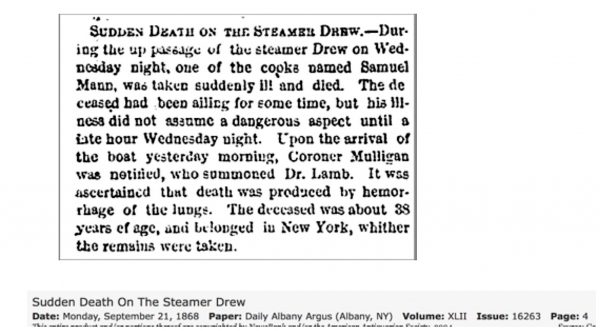

This census record is for New York City in 1855–the same city where the Samuel Mann who is interred at Green-Wood lived at the time of his death thirteen years later. It lists a Samuel H. Mann as 23 years old whose race was listed as “B” for Black. That age is very close to the man of the same name who is interred at Green-Wood–a likely birth year of 1832. Further, several years ago, Sue Ramsey, a great volunteer researcher with Green-Wood’s Civil War Project, uncovered a newspaper report, dated September 21, 1868, of the death of the very same Samuel Mann who is interred at Green-Wood:

According to Green-Wood’s records, the Samuel Mann who is interred in the Freedom Lots was interred there on September 21, 1868. As per cemetery records, he died of “hemorrhage of lung.” So the above report of the death of Samuel Mann, noting the same cause of death and dated the same as the interment, is indeed for the man who is interred at Green-Wood. The fact that he was a cook on a steamship at the time of his death, one of a limited number of professions that, due to racism, was open to African Americans at that time- -and that he is interred in the Freedom Lots –seems to indicate that the Samuel Mann who is interred in the Freedom Lots was in fact an African American. If he in fact he also served in the 132 New York Infantry, what was assumed to be an all-white regiment, that is a significant find!

Similarly, I recently double-checked on the possible installation of a gravestone to mark the grave of an Andrew Schofield. The Andrew Schofield who is interred at Green-Wood in the Freedom Lots was likely born in 1827 and died in 1885. This is the soldier history that I thought matched that of the man of that same name interred at Green-Wood:

Andrew Schofield

Residence was not listed; 35 years old.

Enlisted on 8/13/1862 at Troy, NY as a Private.

On 8/27/1862 he mustered into “F” Co. NY 125th Infantry

* POW 9/15/1862 Harper’s Ferry, VA (Paroled)

* Paroled 9/16/1862 Harper’s Ferry, VA

He deserted on 10/4/1862 at Chicago, IL

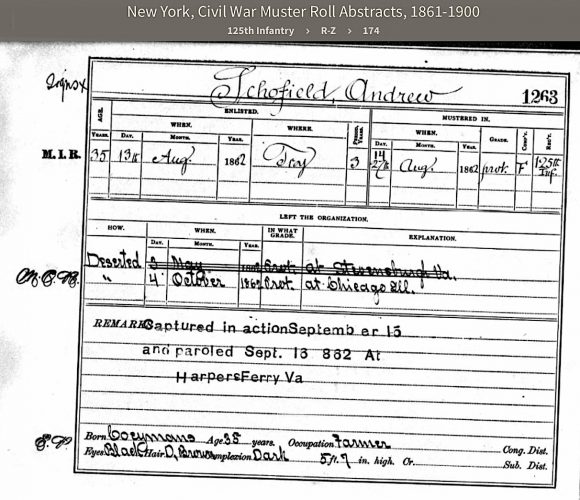

The muster roll for soldier Andrew Schofield records a slightly different story:

Note, first of all, that this record originally recorded that Schofield had deserted on May 3, 1862. However, that made no sense: he had not been mustered into service until August 14, 1862, more than 3 months later than his supposed desertion. Indeed, this error seems to have been caught by a clerk; the date and place of desertion have been crossed out on the muster roll. Further, he is recorded as “captured in action” at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, on September 15, 1862, and paroled the next day. That would be unlikely if he had deserted months earlier. But what is particularly interesting, for the purposes of our discussion, are the notations at the bottom of this document, which describe him as a 35- year- old farmer with black eyes, dark brown hair, who stood 5’7″ and had a dark complexion.

In the 1870 Federal census, an Andrew Scofield (without the “h” of Schofield) is listed as a 40- year- old Black man (born about 1830 in New York), living alone in Manhattan’s 9th Ward, and working as a store clerk.

The 1880 Federal census lists Andrew Scofield (no “h” in his listing) as a 45-year-old living at 224 West 30th Street in Manhattan. He is identified as a Black male laborer, married to Rachel Scofield, and living with her and their four children, ages 17, 13, 11, and 6. The 1888 New York City directory confirms this marriage: three years after Andrew’s death, Rachel Scofield is listed as the widow of Andrew, living at 140 West 19th Street.

While researching Andrew Schofield, I found a man of that name in the 1860 Federal census, living in Westerloo, New York–which is just 29 miles from Troy, New York, where the soldier of that same name had enlisted two years later. The 1860 census further records that Andrew Schofield was 33 years old, born about 1827, was a male, worked as a day laborer, and lived with two women relatives–Frances and Lorinda Schofield. Though there was a column in that census for the census-taker to record “color,” unfortunately this census-taker left the column for “color” blank on the entire page.

The Andrew Scofield interred at Green-Wood is interred in the Freedom Lots, lot 3412, grave 61, with a Mary Scofield. As per Green-Wood’s records, Mary was single, last lived at 154 West 30th Street in Manhattan, and was just short of her 23rd birthday when she died on December 8, 1876. She was interred on December 12, 1876. She died of prerenal uremia.

As I worked on this blog post, I had found no discussion, with the exception of Noah Andre Trudeau’s report of two men of color who served in otherwise all-white units–one joining the march of a militia unit, the other enlisting–of the possibility that men of color might have enlisted, contrary to the rules of the time, in those regiments. We know that hundreds of women managed to enlist and serve during the Civil War, despite a prohibition on such service. I saw no reason to believe that men of color, who largely would have self-identified as to race, could in no circumstances have enlisted in all-white regiments. The fact that two men, both described in their muster rolls as of “dark complexion,” match in many particulars census and other documents for men who served in regiments thought to have been lily-white, and that these men are interred in the Freedom Lots, assumed to be almost exclusively for the burial of people of color, raises the very real possibility that these two men, African Americans, honorably served their country in these regiments before men of color were officially permitted to do so. Indeed, as I concluded my research on this matter, a Green-Wood Historic Fund colleague called my attention to Krewasky A. Salter’s “Combat Multipliers: “African-American Soldiers in Four Wars” (Combat Studies Institute Press, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2003). He writes, in discussing service during the Civil War:

Although the official records state that 178,892 black soldiers served during the war, the actual number may never be known. Since many light-complexioned black troops passed as white at some point and served in white units, and since many black soldiers may have been enlisted into regiments under the same name as a previous soldier who had recently become a casualty, some historians have estimated that as many as 200,000 black troops actually served.

That higher number may include Samuel Mann and Andrew Schofield, two men interred in Green-Wood’s Freedom Lots, who may have served in what were assumed to have been all-white regiments during the Civil War.