Green-Wood has millions and millions of records pertaining to the 574,000 individuals who are interred there. Sometimes the briefest of notations in these records can trigger a search through history–and uncover a long-forgotten story.

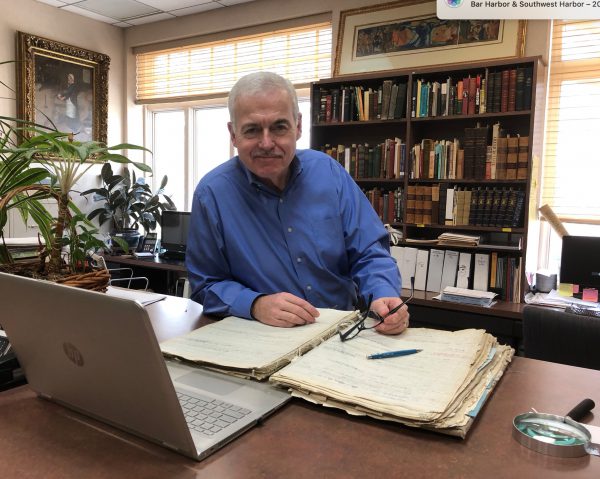

Bob Moogan is a Green-Wood volunteer. Recently retired as an accountant, Bob decided that he wanted to explore history. So, for the past few months, he has been working at processing a collection of lantern slides of New York City, circa 1900, and, more recently, at creating a spreadsheet to help us understand the stories of Green-Wood’s public lots–which typically contain hundreds of single graves each.

In the years that I have been leading tours of Green-Wood, perhaps the most-often asked question I have gotten was along these lines: “Did you have to be rich to be buried at Green-Wood?” Given that question, and the recent shift in history to telling more stories of those who have been largely forgotten, rather than the famous, we thought it would make sense to see what our records told us about those in our public lots, who were interred in inexpensive single graves–as opposed to more expensive family lots of several hundred square feet. So Bob has been diligently working for months now, counting burials of children and adults, recording first and last burials in each public lot, and documenting the broad range of organizations–churches, fraternal organizations– that purchased a lot for its members.

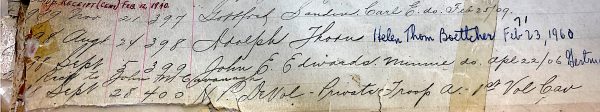

As Bob worked his way through a public lot book recently, he came across these entries–and the last one, with its notation, “Private-Troop A, 1st Vol. Cav.,” caught his eye:

After Bob called my attention to this entry, it occurred to me that this might in fact be a reference to future-President Theodore Roosevelt’s famed regiment, the Rough Riders, who fought in Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

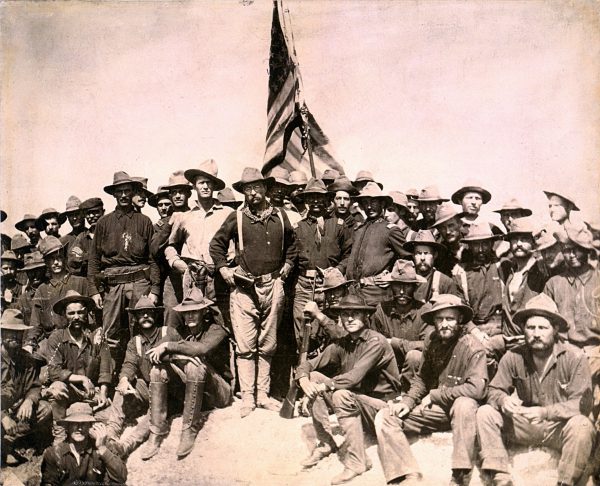

Given the wonders of the Internet, I was almost immediately able to confirm my suspicions: the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, in 1898, was indeed the famous regiment popularly-known as Colonel Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. This is not my first blog post about a member of that regiment who is interred at Green-Wood; I previously told the story of Corporal Charles A. Armstrong of the Rough Riders. So, we have found yet another Rough Rider!

But there was more to this story. Checking Green-Wood’s chronological books, which list all burials at Green-Wood from the first one in 1840 to those made through 1937, we found H.P. DeVol listed for the date and location reported in the public lot books. The entries in the chronological book reported that DeVol, again identified in these books as a private in troop A of the 1st Volunteer Cavalry (such a notation is unusual for these records; they rarely note such military service information), had been born in Ohio, was said to be Dr. Harry P. DeVol, was 35 years old at the time of his death, had died on September 10, 1898, his last residence was in Pueblo, Mexico, he had died at Montauk Point, and that his cause of death was typhoid fever.

His place of death–Montauk Point–also rang a bell. I recalled the Roosevelt’s Rough Riders had camped there–upon their return from fighting in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, they were quarantined against disease, particularly typhoid and other fevers, at a 5000-acre base called Camp Wikoff.

My initial theory, given that DeVol’s date of death was after the Rough Riders had returned from fighting in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, and that he appeared to have been a doctor: DeVol had gone with the Rough Riders to Cuba, heroically treated the sick and wounded there, had himself contracted typhoid fever, and had died upon his return to the Rough Riders’ camp at the eastern end of Long Island. But that theory was to prove to be wrong.

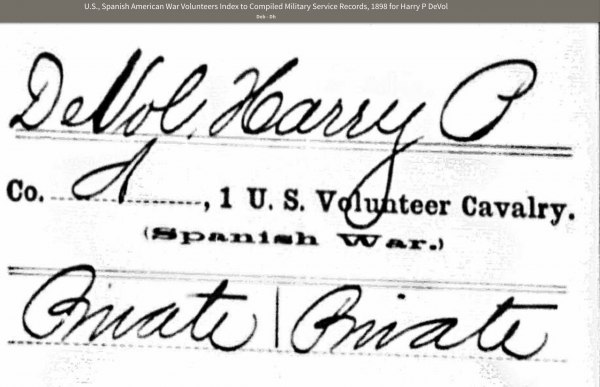

Doing a search on Ancestry.com, I found this military record of Private Harry P. DeVol:

Notably, DeVol enlisted as a private, not as a surgeon or doctor. However, I could find nothing else about DeVol–no city directory, no census record, no report of his death, in this search. His story remained a mystery.

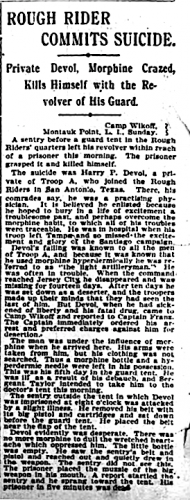

So I turned to a wonderful website run by Thomas M. Tryniski, who, in love with history, has made New York State newspapers searchable online. According to text on that website, it allows for a search of 47 million pages of newspapers from the U.S. and Canada. Eureka! I was soon reading three newspaper obituaries for Harry P. DeVol–one from the New York Herald, one from the New York Tribune, and one from the Albany Times Union. Here is the Herald’s account:

The three newspaper accounts vary a bit. But they are consistent on the core of the story: DeVol, apparently a doctor, was addicted to morphine, never made it to Cuba because he was unfit for duty, and–quite contrary to Green-Wood’s records recording his cause of death as typhoid fever–died of suicide.

So was Harry P. DeVol a doctor? The above obituary reports that DeVol’s comrades “say he was a practicing physician.” The Tribune‘s account states unequivocally that “DeVol was a physician.” And the Albany Times Union was even more emphatic: DeVol “was a well-known physician.” But these obituaries offer no hard evidence supporting this conclusion. So I had my suspicions–perhaps he had claimed to his fellow soldiers that he was indeed a doctor–but he was not. A bit more research established a stronger case for the conclusion that he had indeed been a doctor. In the “Medical Brief” of January, 1893, a journal for doctors, unearthed by volunteer Bob Moogan, a discussion of how to treat addiction includes reference to an earlier article in which it was stated that “Dr. H.P. DeVol wants help for opium habit” and in which DeVol is referred to as a “brother physician.” Note that morphine, to which Private DeVol was addicted, is a natural substance derived from the opium poppy–hence the reference to opium here, as opposed to morphine in the obituaries. This report in “Medical Brief” would seem to confirm, given the rarity of the name “H.P. DeVol,” that our subject was indeed an addicted medical doctor as of 1893–six years before his death.

The Albany Times Union got even more creative–and wandered from the facts–in other aspects of its obituary, declaring DeVol “a brave man” who had ended his life honorably: “It was a suicide–the final act of one of the Rough Riders–a brave man who, finding himself conquered by an appetite and disgraced before the world, calmly put an end to his career in the accepted western manner with a six-shooter.” As per that newspaper, perhaps in a further flare for the dramatic (neither of the other two newspapers reported this as fact), it was reported that “a morphine bottle and a syringe” were found by DeVol’s body.

So how is it that Green-Wood’s clerk recorded Harry P. DeVol’s cause of death as typhoid fever–and made no mention of suicide? I have seen this practice before in Green-Wood’s records–given the social and religious stigma of suicide, particularly back then–a reluctance to record cause of death as suicide–and creating a false reality. Perhaps the undertaker, perhaps the clerk at Green-Wood, is the source of this false report.

We don’t know for sure that Harry P. DeVol was a doctor–though it does seem likely. Nor do we know that he was a brave man. We do know that he volunteered for and served in the 1st New York Volunteer Cavalry, known far and wide as the Rough Riders, that he was addicted to morphine (which made it impossible for him to go off to Cuba to fight), and that he died a tragic death by suicide. Sadly, his grave is unmarked.

Thank you for another fascinating story! I am pleased to learn that Bob Moogan is making new discoveries about the people buried in the public plots at Green-Wood. In 1880 my 2nd great grandfather, Andrew Wood, was buried in public lot 8999 Grave 1136. It is an unmarked grave and I have often thought that it is sad that we don’t know more about these early burials. I have done some research, with the assistance of Green-Wood, and learned that Andrew Wood was a mason who worked on the construction of St. Patrick’s Cathdral. When he retired from masonry he began a milk business with his son. Shortly into the new venture he fell from the milk wagon and met his death. Several family members are also buried in this plot. Thank you for keeping some of these stories alive.

Thanks, Karen, for your kind note. And thanks for sharing the story of your ancestor. A cemetery, above all else, should be a place of remembrance–and such stories–the one I wrote and the one your shared–help us remember. A couple of years ago I donated my collection of stereoviews of New York City, dating 1860-1920, the The Green-Wood Historic Fund. We have volunteers cataloguing them now–and hope to put them online when this work is done. I know that several of them show St. Patrick’s being built. If you’d like, I will send you scans of one or two, showing the stones cut and ready to be placed by the masons, including your 2nd great grandfather.

My thanks to all those who participated in the research and writing of this fascinating and dispositive article:-)