Visitors to Green-Wood today are welcome to explore the cemetery on their own, with the help of maps, apps, and/or self-guided walking tours, or on a tour led by a Historic Fund tour guide. But what, you may wonder, was it like to explore Green-Wood in its early years, soon after its founding in 1838?

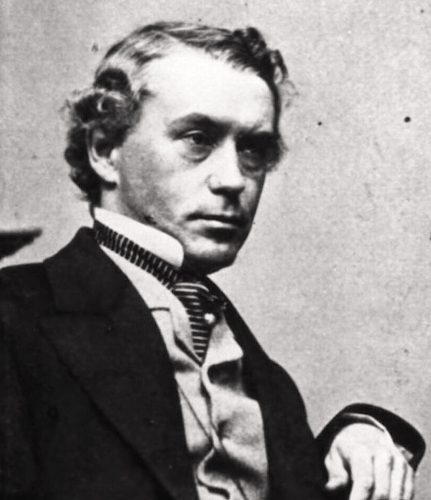

Fortunately, we can get a sense of Green-Wood’s early years, courtesy of George Templeton Strong (1820-1875). Strong was a lawyer, trustee of leading New York City institutions (including Trinity Church and Columbia College) and one of the leaders of the United States Sanitary Commission. It was that organization which during the Civil War saved thousands of lives of Union soldiers by preventing and treating disease as well as by giving medical care to the wounded and keeping track of the dead. During the Civil War, Strong, in his capacity on the executive board of the Sanitary Commission, met with President Abraham Lincoln in the White House.

Strong is best remembered today for his remarkable diary of life in New York City, in which he recorded his perceptive, often humorous, insider observations, and his virulent prejudices, on an almost daily basis from 1835 until his death, forty years later, in 1875. It is, without a doubt, the most interesting diary of 19th century New York. Not written with publication in mind, Strong’s diary was first published with the permission of his ancestors in 1952, and is now widely available in several editions.

Strong was a man of great curiosity. He constantly was exploring New York City and its environs–uptown Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Hudson–and as far as upstate New York, New England, and more.

Certainly one of the curiosities of 19th century New York was the emergence of Green-Wood Cemetery as a leader of the rural cemetery movement. Strong visited Green-Wood several times, there to explore and render his judgment. Green-Wood was chartered by the State of New York on April 18, 1838. Strong came for his first visit just a year later, before any burials had been made–while improvements were being made to the grounds, roads and paths were being laid out, hills contoured, the soil improved, and plantings made.

Strong had seen many of the churchyards of lower Manhattan sold off for commercial development. He knew that bodies that had been buried in them, with the expectation that they would stay there forever–but that that had not been the case. As land in lower Manhattan became more and more valuable, congregations sold off their churches and churchyards and moved uptown. Notices went up–claim your dead. But, when bodies went unclaimed despite such warnings, they were unceremoniously dug from the ground and carted off to the Potter’s Fields. Strong had seen caskets broken apart, with arms and legs dangling, heading up Broadway to be buried again. Given that experience, he was very favorably impressed with the permanence that interment at Green-Wood offered. So, just over a year after Green-Wood’s founding, he wrote of his first visit to Green-Wood:

July 27, 1839: . . . After dinner, took the carriage and went with Mr. Bidwell over to the “Greenwood” Cemetery–a most exceedingly beautiful place it is, and I sincerely hope it won’t turn out a bubble, for in this city of all cities some place is needed where a man may lay down to his last nap without the anticipation of being turned out of his bed in the course of a year or so to make way for a street or a big store or something of that kind, and this place, when it is a little improved and cleared up, will exceed Mt. Auburn . . . .

Strong’s above reference to “Mt. Auburn” is to that of the first rural cemetery in America, founded in 1831 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to service the greater Boston area. Rural cemeteries, which trace their roots back to Pere Lachaise in Paris, France, aimed at locating burials away from densely-populated cities and putting them in then-rural areas, but keeping them close enough to population centers that a convenient one day visit, by horse or carriage, could be had.

Five years later, in the 1840s, Green-Wood was struggling to establish itself as an ongoing business. It was battling two primary traditions: that of people being buried in the churchyard of the church they had attended all of their life, and the idea that one would be interred only with fellow congregants of one Christian sect. Green-Wood broke with both of those traditons. By design, it was not contiguous with any church and offered a non-sectarian Christian burial–with Episcopalians, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Methodists, and others, all in the same space. Strong was back at Green-Wood in 1844–this time lauding the cemetery, but, as a conservative religious man, criticizing “pagan” imagery there:

April 25, 1844: . . . Started for the Greenwood Cemetery with Templeton at four o’clock and walked there, traversed the grounds, and walked back by half-past seven, a pretty fair afternoon’s walk, and I confess to a pair of feet a little exacerbated and one or two extensor muscles a little sore. Beautiful place it is, and they’re hard at work improving it, putting it all in good order. When it’s brought to the same high state of civilization with Mt. Auburn, it will far surpass it. I’m glad to see that what Pugin calls the “revived Pagan style” doesn’t prevail very extensively there. I only noticed one pair of inverted torches and not a single urn or flying globe or like silliness, only not profane because it may be supposed to be unmeaning. This recurrence to heathen taste and anti-christian usage in architecture or art of any sort is or should be unreal and unnatural everywhere, but in such a place as that, it’s disgusting. But when churches are modeled after Parthenons–even to the bulls’ heads and sacrificial emblems on the frieze–of course it’s not wonderful that people will cover their tombs with the symbols of Paganism.

On April 10, 1858, by the time Green-Wood had achieved financial stability and become a major tourist attraction, second in America only to Niagara falls, Strong was back in Brooklyn, near Green-Wood, remarking on the rapid increase in the number of homes nearby:

I could not refuse the invitation of today’s sunshine. I strolled out with George Anthon on some frivolous pretext or other, walked farther than I intended, and roamed far away, at last, among the remote regions of Southern Brooklyn, near Gowanus and the place where was of old the Penny Bridge. The growth of that region is marvelous. A great city has been built there within my memory. The compact miles of monotonous, ephemeral houses which overlook the Greenwood Cemetery ridge impress me as does some great reef half bare at low tide and dense with barnacles. Each is a home, each is throwing out its prehensile cilii into the great sea, with better fortune or worse, good investments or bad, credit or disrepute, progress up or down. Each has (or had) its children, its young girls, its boys hopeful or otherwise, its own domestic history and prospects, its memories of joy and sorrow, each is an epitome of human life within each shabby domicile . . . .

A few years later, Strong would attend a funeral at Green-Wood for his good friend, George F. Allen.

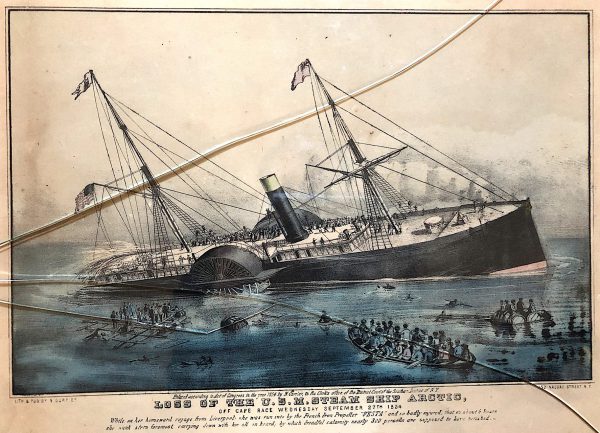

Tension built in New York City early in October, 1854, when the steamer Arctic, the largest and fastest ship on the seas, was past due from England with members of many of New York’s leading families aboard. In the absence of any communication coming from the ship (radio communication did not then exist), anxiety increased day by day. As Strong wrote in his diary on October 6: “The Arctic considerably past due; some uneasiness about her. George F. Allen is on board.” Three days later, Strong noted: “Artic still missing; people who’ve friends on board begin to talk nervously about her.”

On October 11, word of the fate of the Arctic finally reached New York City. It had sunk on September 27 after colliding at sea, in heavy fog, with a much smaller ship, the Vesta. The Arctic’s crew had manned its pumps after the collision, trying to keep her afloat. But the crewmen had soon abandoned their posts to storm the few lifeboats on the ship, saving themselves but leaving all of the women and children, and many of the men, to drown. Not a woman nor a child survived the sinking. Of the 335 people on board, 250 were lost. The aforementioned George F. Allen survived the sinking, but his wife and child, as well as four other relatives, did not.

George F. Allen lived for another 9 years after the Arctic disaster. On August 31, 1863, Strong attended the funeral of his good friend, George F. Allen, at Green-Wood:

Home at one P.M. Arrayed myself in decorous black, went to 823 Broadway, attended to certain business, and proceeded thence to Horatio Allen’s, 25 Clinton Place, being invited as a pallbearer. . . . We marched from the house to Grace Church. Dr. Taylor mangled and bungled the service most hideously. Thence in carriages to Greenwood Cemetery. There were only pallbearers and relatives. It was a long drive. The lawns and shrubberies of the cemetery were lovely in the slant sunlight of the autumnal afternoon. Grecian temples, urns, obelisks, broken columns, and many other monumental enormities could not quite destroy their loveliness. Our carriages stopped at last; we got out and saw marks of recent laceration on the beautiful greensward of the James Brown’s lot. The coffin was brought forth from the hearse and went down into the earth, and then came the grating clatter of stones and sods on its lid. Poor Horatio Allen and his wife and others of George F. Allen’s near relatives seemed to take it very hard, and no wonder. It seems hardly credible that George Allen’s face and form, so familiar and so welcome in this house for many years, so full of gentility and sympathy, sagacity, keenest intelligence, high culture, appreciation of art, devotion to the nation and to the church, should now be lying under six feet of earth. He lies beside his two elder children, who died before 1854, and his brother William. His wife and his third child rest fathoms deep in the ocean, near the sunken wreck of the fatal steamer, the Artic.

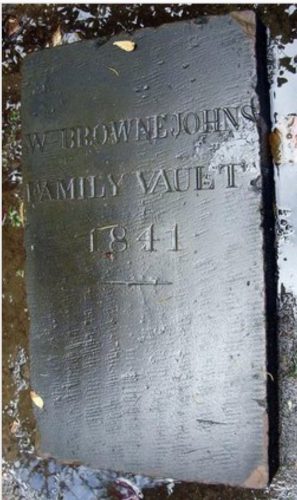

Given that George Templeton Strong was a trustee of Manhattan’s Trinity Church, and that he worshiped there for much of his life, as well as the fact that his in-laws owned an underground vault in its churchyard, it is not surprising, despite his enthusiasm for Green-Wood, that he is interred in Trinity’s graveyard:

Greetings Sir.

I recently read book about first ocean rowers from NYC to UK couple of Norwegian men who left NYCV in 1896 one of them was George Harbo who passed 12 year later of pneumonia 1908 and was buried at Green-Wood cemetery. I am wondering if you have record and or know location of his grave. I am about to solo row Atlantic Ocean myself and would like to pay him respect especially since I am sure nobody really knows about him and or his grave to me he was a pioneer. I’d understand if you didn’t know I am sure the record keeping from those days were perhaps not the best. Thank you very much either way. Sincerely Milan

Yes, Harbo’s voyage is quite a story!

He was interred on 1908-04-07 in lot 27263, grave 1322, in section 135. That is a public lot, in which graves are arrayed in a grid. When you arrive at Green-Wood, go into the office, explain that you have come from abroad, and that you would like maps that will make it possible for you to find this grave.

Have a great visit!

Hello Mr. Richman,

I learned that the son of Dunbar Almond Fisk, aka the inventor of ‘Fisk metallic cases’, (Dr. William Meade Lindsley Fiske) is buried in Green-wood, along with the rest of his family members (Alas, Almond Dunbar Fisk is interred in

Riverview Cemetery, Chazy, Clinton County) Since these metallic cases revolutionized the American way of death/funeral industry, (as they are credited as the progenitor of the metal caskets used today!)I thought the Green-wood connection would make a good story, there is even a blog dedicated to Fisk burial cases of the 1850s http://ironcoffinmummy.com

Thanks for sharing this information. I will see what I can find.

In 1898 how would someone travel from Manhattan to Green-Wood. Was there a ferry?

Yes, there were several ferries. And the Brooklyn Bridge had opened in 1883. Plus you could take mass tranist–there was an elevated railroad stop near the cemetery’s main entrance.

I believe the 2nd image captioned “ An engraving of a family lot at Green-Wood, by James Smillie, from Cleaveland’s 1843 guide.” shows the King family lot, section 147, beginning with Charles King 1827-1899