I recently met at Green-Wood with Professor C. Cuvaj. I know him from several Green-Wood tours he has attended. He is a retired physics professor who is fascinated by cemetery art. A man of great curiosity, he always has questions and is ever eager to learn more. So, for instance, he is compiling a database of all of the artists’ monuments at Green-Wood that have a painter’s palette on them. He also is photographing all of Green-Wood’s metal mausoleum doors. And, he has recently researched the work of the most revered of New York’s late 19th and early 20th century architects: McKim, Mead & White. The principals in that firm, which was started in 1879, were Charles McKim, William Mead, and Stanford White.

Dr. Cuvaj was able to track down what was described to him by Andrew Dolkart, director of Columbia University’s Historic Preservation Program, as the best source on this architectural firm: a thesis at the Avery Library of Columbia University by Leland M. Roth, published in 1978 as The Architecture of McKim, Mead & White, 1870-1910, A Building List. Roth begins his preface with this: “For more than a quarter of a century, McKim, Mead & White was the largest architectural firm in the world, producing buildings of a quality and at a rate that impressed colleagues and the public both in the United States and in England.” Roth’s book contains an extensive alphabetized list of the firm’s work, including buildings as well as cemetery mausolea and monuments. It lists five works by that firm at Green-Wood. Dr. Cuvaj generously shared his research with me–and I was able to find much more information–including being able to identify a few unlisted McKim, Mead & White works at Green-Wood, as you will see below–with further research.

One of the works at Green-Wood that is listed by Roth is the Stewart Mausoleum. I have long known about that work by the extraordinary architect Stanford White and the great sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. White and Saint-Gaudens collaborated on about a half dozen cemetery pieces, including the haunting Adams Memorial (built 1891-1892) in Washington, D.C.’s Rock Creek Cemetery and the design for New York Governor Edwin Morgan’s tomb, which was planned for Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut (but was never built because the sculpted pieces were destroyed by fire). White and Saint-Gaudens also worked together on several public sculptures, including the Admiral David Farragut Monument in Madison Square Park (dedicated in 1881). Saint-Gaudens also collaborated with White’s partner, Charles McKim, on the equestrian statue of Civil War Major General William Tecumseh Sherman (dedicated in 1903) that stands in Manhattan’s Grand Army Plaza.

This is the Stewart Mausoleum at Green-Wood:

The Stewart Mausoleum was cutting edge art when it was unveiled in the 1880s, controversial for the faces of its angels depicting death as something other than a mournful experience. Indeed, when White saw Saint-Gaudens plans for the Morgan tomb, at about the same time as they were working on the Stewart Mausoleum, he urged his partner to write to their patron to explain its novel depiction of death as resurrection, a rebirth, cautioning him: “Some people are such God damned asses they always think of death as a gloomy performance instead of resurrection.” The angels that Saint-Gaudens designed for the Stewarts were not to be “a gloomy performance.” The Stewart Mausoleum is in section 109 of Green-Wood, right along Battle Avenue at its intersection with Arbor Avenue, just feet from Green-Wood’s magnificent Gothic Entrance Arches.

Roth’s information on the Stewart Mausoleum is limited. He lists its customer as “D. Stewart” (for David Stewart) and terms it a “monument” rather than as a mausoleum. He adds that its construction was begun circa 1885 and its architect was Stanford White.

In section 65, lot 33055, between Vine Avenue and Celastrus Path, stands the monument memorializing Frank Lusk Babbott (1854-1933) and Lydia Babbott (1858-1904). Frank Babbott was a Brooklyn banker, jute merchant, art collector, and philanthropist. He had a great passion for education, serving as vice president of the Brooklyn Board of Education, then as a member of the New York City Board of Education. He was on the board of Pratt Institute and was for many years president of the board of trustees of Packer Collegiate Institute. He served as the honorary president of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, now known as the Brooklyn Museum. In 1925, he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor of France for his lifelong work in education. He was also a trustee of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Vassar College, the YWCA of Brooklyn, and the Brooklyn Public Library. Upon his death, the Brooklyn Eagle described him as “a public benefactor” and concluded, “His was the highest type of good citizenship.” A very wealthy man, he left $1.5 million in his will for a fund to support medical education, the equivalent of almost $29 million today. And that was just a part of his philanthropy!

Given his wealth, Frank L. Babbott could afford the best for himself and his wife, Lydia Pratt Babbott–and he hired McKim, Mead & White to design their memorial at Green-Wood. It dates from 1909–five years after her death. Babbott had strong ties to that architectural firm. He was the president of the Brooklyn Institute when McKim, Mead & White built its magnificent building–still standing today. Both Babbott and architect/partner William Mead were graduates of Amherst College. When Babbott’s good friend George Eastman (of Eastman Kodak fame) asked Babbott to be his design consultant on Eastman’s Rochester mansion, Babbott brought in Mead to work with Eastman. So it is no surprise that Babbott, in his mid-50s, already a wealthy man and contemplating his mortality, hired McKim, Mead & White to design his fine memorial at Green-Wood.

As per Roth, the Babbott Monument at Green-Wood was erected in 1909 at a cost of $2060–the equivalent of just over $54,000 today–a very substantial sum.

The memorial to John Innes Kane, dating from 1914 (a letter from McKim, Mead & White, dated June 13, 1914, in Green-Wood’s archives requests that the cemetery proceed with “building the foundations, including eye (sic) beam, reinforced concrete, etc.”; it notes that the “sacrophagus” would be completed by the end of the month), is located in section 80, lot 1696, just to the right of the entrance to the Egyptian Revival mausoleum of Peter Schermerhorn and family (dated 1847 above its entranceway). The Kane Memorial, a sarcophagus decorated on its top, ends and sides, has both extraordinary lettering and elegant carving.

Kane, who died in 1913, was related to many of New York’s leading families; his grandfather was John Jacob Astor, his wife was Annie C. Schermerhorn (Peter Schermerhorn’s granddaughter). The Schermerhorn Mausoleum, just behind Kane’s memorial, was built in the midst of the 100 acres that the Schermerhorn family sold to Green-Wood Cemetery in its earliest years–the knoll upon which it sits had been the location of the Schermerhorn’s barn. Kane was a great fan of scientific explorations and funded many. It appears he lived off his inheritance; as one obituary reported, “he never engaged in business.” He was a member of New York’s leading clubs, including the New York Yacht, Knickerbocker, Union, South Side Sportsmen, Automobile Club of America, and Metropolitan.

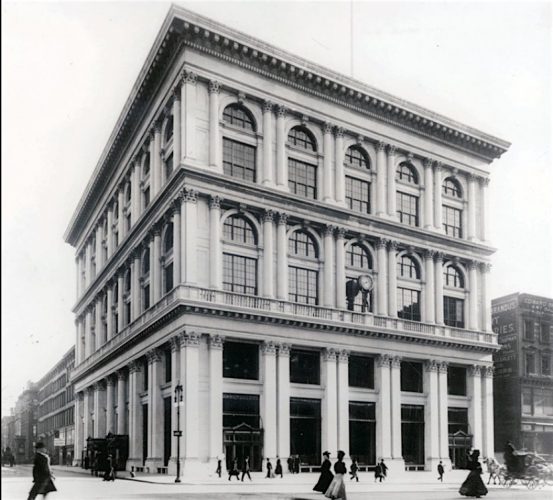

As per Roth, in 1904 Kane hired McKim, Mead & White to plan his residence at 610 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. It was designed by Charles McKim and his principal assistant, William Symmes Richardson, at a cost of $511,472 (approximately $13,759,000 in today’s money). It has since been demolished–Rockefeller Center stands there now.

This McKim, Mead & White work–John Innes Kane’s spectacular house–must have pleased his heirs; they hired the same firm to design the beautifully-detailed sarcophagus in front of his in-laws tomb. Roth mistakenly describes the Kane Memorial as a “mausoleum.” He further states that it dates from 1914, cost $4842 (just over $120,000 in today’s money), and that the original drawings for it survive at the New-York Historical Society.

I asked Green-Wood’s manager of restoration and preservation, Neela Wickremesinghe, for her observations on the stone used for the Babbott and Kane memorials. Here’s what she wrote in response to my question whether they are limestone:

Close guess on the limestone, but it is actually a material called Tennessee Pink Marble, it is a type of sedimentary limestone, but it lacks the true uniformity of a classic Indiana Limestone with its telltale encapsulated trilobites. It was used throughout New York on a lot of McKim, Mead, and White structures. Both monuments use it in its unpolished form, which is rough to the touch. The James Wall Finn monument (note: also at Green-Wood–see its story here) is also Tennessee Pink. Overall they are both in very good condition with a bit of biological growth at the undercuts, but nothing serious. The Kane monument has a tight crack running from the top right of the monument towards the center, but aside from that it looks great.

In section 70, lot 1792, visible from Vista Avenue, and near Vista Path, is the McKim, Mead & White memorial to the Cromwell family. Frederic Cromwell (1843-1914) graduated from Harvard in 1863 and went into the insurance business; for twenty years, he was the treasurer and a trustee of the Mutual Life Insurance Company. He also was a director of many railroads as well as a bank, an engraving company, and a coal company. He died at his estate, Ellis Court, in Bernardsville, New Jersey.

The great craftsmanship of this memorial is immediately apparent: it is wonderfully carved and finely detailed. The inscriptions for Frederic and his wife, Ester Husted Cromwell, are on the same panel. Note that I blogged about their twin daughters (“A Twin Tragedy”), who served as nurses in France during World War I, then killed themselves by jumping from the transport ship that was bringing them back to America. Their names and life dates are recorded on the panel at left in the photograph below; the top edge of the slab that is the sisters’ centotaph is at the bottom left of this photograph:

According to Roth’s list of McKim, Mead & White projects, in 1894 they built a tower for Frederick Cromwell in Bernardsville, New Jersey, where he lived, charging $1976, with Sturgis Brothers as the contractor on the project. In 1911, again as per Roth, Cromwell hired McKim, Mead & White to create his memorial at Green-Wood; the cost was $1,784 (just over $45,000 in today’s money).

In the same lot, just a few feet away, I noticed this gravestone:

By coincidence, as I was working on this blog post, I was copied on an e-mail that included this photograph:

Samuel G. White, great grandson of Stanford White, and an architect himself, is the co-author, with his wife, Elizabeth White, of Stanford White, Architect. Sam, who is also a member of Green-Wood’s board of trustees, comments on Wells: “Wells was the employee of McKim, Mead & White who persuaded the partners to look at Italian Renaissance architecture for inspiration, and he is generally credited as the author of the elevations of the Villard houses. So he is an important, if somewhat neglected, figure in the history of American architecture.” As per Roth, when Stanford White joined McKim, Mead & White in 1879, there were already four draftsmen working there, including Joseph Morrill Wells. Roth describes him: “Wells was extremely gifted, not so much in plan organization as in the study of detail and ornament, and his contribution was so significant that in 1889 he was offered a partnership that, enigmatically, he refused. He died of pneumonia the following year.”

Note the similarities in the layouts of the Ellis Cromwell and Joseph Morrill Wells gravestones: a classical motif at the top, then an architectural cornice below it, then two bosses, then the inscription. Further, notice the similarity of the design of the two bosses–the round stone protrusions–on each of the gravestones.

UPDATE: Soon after this blog post went up, Corinne Barrasso Troiano posted this comment on Facebook:

Interesting post! I knew Stanford White was buried in Saint James, Long Island, but wasn’t sure where. Easter Sunday a few years back, I had a hunch he was buried in the small churchyard. near the restaurant where we were having dinner. I got out of the car and walked right up to his grave! As you can see, his monument (and the tiny identical one next to it belonging to his small son) closely resembles the Ellis Cromwell and Joseph M. Wells memorials you mention in your post.

She then added this link to the images at Find-A-Grave of Stanford White’s own gravestone. Quite a find!

Sam White comments on the Ellis Cromwell gravestone: “There is no record of the stele for Ellis Cromwell, which is not surprising. Roth only transcribed commissions with a fee of more than $100 and they either did this one as a favor for a bereaved family or they charged them less than $100. But it certainly looks like the real thing.”

Roth also lists a monument at Green-Wood, dating from 1914, with Mrs. William Bayard Cutting as the customer. As per Roth, it was built at a cost of $100 (about $2500 today). This is, in fact, the slab for her husband, William Bayard Cutting (1850-1912), in section 23, lot 7929. It is along Wood Girt Path, just off of Tulip Avenue. I previously blogged about William Bayard Cutting and the spectacular Cutting estate (“Home, Sweet Home”) that is now New York State’s Bayard Cutting Arboretum–all 691 acres of it. William Bayard Cutting made his money in real estate, law, finance, and as a pioneer of sugar beet refining. He built railroads, ran ferry companies, and developed the Red Hook section of Brooklyn. The first private golf course in America was built on his estate in 1895. In that same year, a fire destroyed many of his farm buildings there. Undeterred, and apparently with no shortage of cash, Cutting hired none other than Stanford White to design a modern dairy and other new features for his estate. Though White was murdered in 1906, on the roof of the spectacular Madison Square Garden he had built across the street from the northeast corner of Madison Square Park, the Cutting family clearly was pleased with his work for them, and hired McKim, Mead & White, after White’s death, to design William Bayard Cutting’s gravestone.

Directly to the right of William Bayard Cutting’s gravestone is that of his wife, Olivia. Though her gravestone does not appear on Roth’s list, it seemed to me that it might have been made by McKim, Mead & White. Though the founders of that firm were dead by 1928 (Charles McKim died in 1909; William R. Mead died in 1928), the firm was still in business into the 1960s–and therefore could have done this work in 1949, upon Olivia’s death. Further, these two tablets share a similarity of design and material. Note, also, that Olivia’s tablet, dating circa 1949, was meant to be a complement to that of her husband: the top line of his marker reads “William Bayard Cutting” and the top line of hers, directly to the right, reads “And Olivia His Wife.” Their gravestones are not just similar in design, but were designed to work together–a very nice touch in memorializing a husband and wife.

Papers in Green-Wood’s archives have helped us solve some of the mystery of whether McKim, Mead & White designed Olivia’s gravestone. In the burial orders for this lot, I discovered several documents on McKim, Mead & White stationery. Interestingly, one document, dated May 6, 1937, establishes that there were four large graves in that lot, surrounded by a concrete vault, three of which were then occupied, from left to right, by the remains of William Bayard Cutting (son of William and Olivia), who died in 1910, William Bayard Cutting, who died in 1912, and Bronson Cutting, son of William and Olivia, who served as United States Senator from New Mexico and died tragically in a plane crash in 1935. In 1937, at Olivia’s request, the remains of their son, Bronson, were moved one grave to the right, making it possible for Olivia to be interred, upon her death, between her husband and her son.

Further, in a second letter, dated April 20, 1937, on McKim stationery, Lawrence Grant White, the son of Stanford White and himself a partner in the firm, wrote to Green-Wood: “I have designed a gravestone for grave no. 4 . . ..” That would be Bronson Cutting’s grave:

Another document, also dated May 6, 1937, and signed by McKim, Mead & White as agents of the Cutting family, hired Joseph Donnelly of 335 East 46th Street, who advertised as “Architectural Sculptors” in the business of “models and stone carving,” to prepare “the Bronson Cutting ledger stone” and for “cutting an inscription on the border of Wm. Bayard Cutting’s Memorial.”

Olivia Cutting died on November 15, 1949. By letter dated December 20, 1949, the firm of Presbrey Leland, “Designers and Builders of Monuments and Mausoleums,” headquartered at 681 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, wrote to Green-Wood as follows:

In 1946 we furnished a ledger memorial for Mrs. Olivia Cutting (Mrs. W. Bayard Cutting) to duplicate others on the lot and to be held in storage until her death, which occurred on November 15, 1949. We have carved the death date on the ledger, and would like to set it in the cemetery when weather conditions will permit.

So, based on these letters in Green-Wood’s archives, the involvement of McKim, Mead & White in the design of these gravestones in the Cutting lot is clear.

So what does all of this information about these memorials at Green-Wood tell us? McKim, Mead & White did not work cheaply–their customers would have needed a lot of money to hire them. Those customers wanted the best, and typically they had worked earlier with the McKim firm on some other project outside the cemetery. It is apparent, as we look at this group of monuments, that both the design and execution of these pieces were exceptional. One can readily appreciate McKim’s work at Green-Wood as much superior to the typical monument maker’s work there.

Professor Cuvaj was able to determine that Roth’s list likely is incomplete, based on known works by McKim, Mead & White at Woodlawn Cemetery that do not appear on that list. Indeed, as I was working on final edits of this post, I came across an entry in Roth’s list for the Tiffany & Company store and offices that were built at 401 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. As per Roth’s entry, that building was designed by Stanford White, built 1903-1906, is still extant, and cost the incredible sum of $2,061,737 (the equivalent of $55 million today). It dawned on me, upon reading this, that in fact one of the columns from that building–designed by McKim, Mead & White–now stands at Green-Wood, in section 97, just off the intersection of Grove and Central Avenues, in the middle of Acorn Path. Sarah Amelia Hewitt went shopping at this Tiffany’s store one day, did not find a bauble worth buying, so instead bought one of the columns from inside the building to place as a memorial at Green-Wood for her deceased husband. Here is that building, soon after its opening:

After Mrs. Hewitt purchased the column just a few years after her husband’s 1903 death, she had it installed on the Cooper-Hewitt island at Green-Wood, where her husband was interred. In 1932, the Hewitts’s son, Erskine, donated the column to the Hewitt Annex at Cooper Union as a memorial to his father. So it journeyed back to Manhattan, then came back to Green-Wood just a few years ago, when the Hewitt Annex was remodeled. Here it is, being lifted by crane up above the Cooper Union:

Here’s what it looks like, re-installed at Green-Wood:

I recognize several names on Roth’s list of people who hired McKim, Mead & White for projects as individuals who are interred at Green-Wood. Further research may reveal that some of these individuals also hired the firm to do their memorials at Green-Wood. So there likely are more McKim, Mead & White finds to be made at Green-Wood! Anyone have any ideas?

This is a wonderful account focusing on the participation of a single architectural firm in the creation of the tapestry of Green-Wood Cemetery over a sixty-year period. It is just one of the many, many ways that Green-Wood provides the structure for a dive into history.

I love this information. I have an original facade drawing of the John Inns house. I am thrilled to have this photo of the completed house!