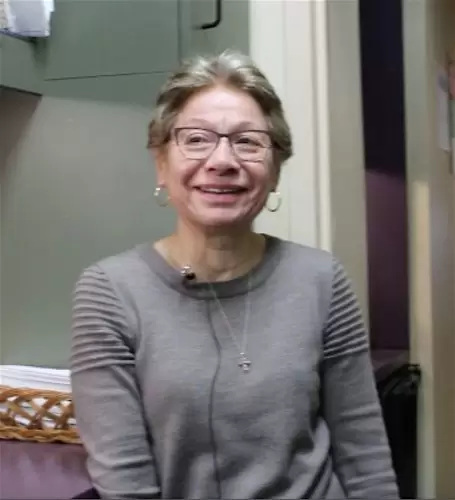

Theresa LaBianca started working at Green-Wood Cemetery in 1977 as an administrative assistant. She has just retired. In the almost 41 years she was at Green-Wood, Theresa did a lot of day-to-day work with Green-Wood’s records, helping it function as a cemetery. But it is clear that the best part of the work, as far as Theresa was concerned, was “solving the mysteries. Finding out who was buried here. Not just the name . . . but finding out who the people were, what they did for a living, how they lived, were they rich, were they poor, were they good, were they bad? Very interesting!”

When Theresa retired, she left the files that she had been working on–the mysteries she had been trying to solve–for our archives. Reviewing those files, one rather thick folder caught my attention. Theresa had been on the trail of an Archibald Robertson (1765-1835), who was a leading early New York City artist and a prominent painter of miniatures. His work is prized in today’s art market. And the mystery was whether–despite the fact that his name appeared in none of the cemetery’s records of burials–his remains had in fact been interred at Green-Wood Cemetery.

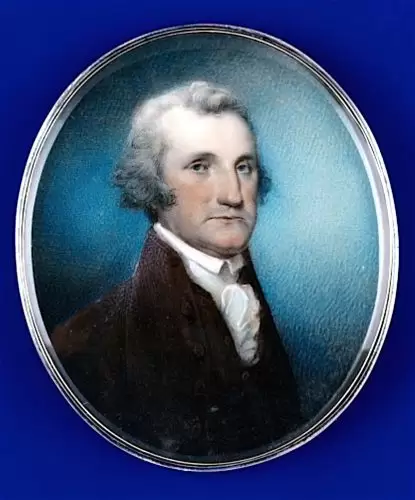

Who was this Archibald Robertson? Born in Scotland in 1765, Robertson attended college in Aberdeen, then studied in London with two of the leading artists of the time, Joshua Reynolds and Benjamin West. Robertson also studied art at the Royal Academy. Returning to Scotland, he painted portraits, both full-sized and miniatures, and collaborated with his brother Alexander on engravings.

In 1791, Archibald, at the invitation of several wealthy New Yorkers, immigrated from Scotland to New York City. The next year, his brother Alexander joined him, and they together ran the Columbian Academy of Painting there, what may have been New York’s first art school and was certainly one of America’s first art schools. Well-known for his miniature portraits, Archibald Robertson went to Mount Vernon in Virginia late in 1791 to paint portraits of George and Martha Washington. He stayed at Mount Vernon for three weeks, painting miniature portraits from life of George and Martha Washington as well as two oil paintings of the general; Archibald and George became friends.

In 1794, Archibald Robertson married Eliza Abramse; he taught her to paint and her work was exhibited at the American Academy of Fine Arts. Archibald became a member of the Academy in 1817 and served as a trustee for 15 years. He also was one of the pioneers of American landscape paintings.

Theresa, in her research, found a newspaper report that Robertson had died on December 6, 1835, and was interred within days at the North Dutch Church in Manhattan. That church opened in 1769 on the northwest corner Fulton and Williams Streets. Here it is:

During the Revolutionary War, the British desecrated this church, shipping its pulpit off to England and burning its pews and woodwork for fuel. They used the church to store grain, as a hospital, and for the imprisonment of up to 2,000 poor souls at a time. After the British evacuation in 1783, the church was restored. Here is a photograph of its fine interior, as it looked circa 1860:

When it first opened, the church was in a residential area. However, as Manhattan developed and businesses increasingly moved uptown, the area where the church stood became increasingly commercial. This caused homeowners to move uptown to more attractive residential neighborhoods such as Union Square and Madison Square. And, as a predominance of newspaper offices moved into the area around the North Dutch Church, more and more residents moved away, and more old residences–even those that had been converted for commercial use–were torn down and replaced by new, and larger, structures. In 1873, James Gordon Bennett, Jr., who had taken over the New York Herald from his father (who is interred at Green-Wood), purchased the land where the North Dutch Church had stood for a century and had the 7-story cast iron Bennett Building built there (where it still stands).

Theresa was able to trace Archibald Robertson’s family to lot 6736 at Green-Wood. In that lot, through genealogical research, she identified his immediate family members: Alexander H. Robertson (either his brother or his son), his brother William Andrew Robertson (both interred April 8, 1853–apparently removals from a burial ground), his wife Eliza Abramse Robertson, and his son Anthony Lispenard Robertson.

Further, Archibald Robertson’s daughter Rachel A. Winslow and father-in-law Jacob Abramse were “Removed from North Dutch Church,” where they had been buried, and were interred at Green-Wood on June 11, 1862. Notably, a “box of bones” arrived on that same date with his daughter’s and his father-in-law’s remains–the undertaker for all three was James Dunshee–and was interred in this Robertson Lot on that very same date, also having come from the North Dutch Church.

The “box of bones” is particularly important to our search. As churchyards were sold off for commercial development in 19th-century lower Manhattan, bodies were claimed by families, disinterred, and re-interred elsewhere. Given these circumstances, it was not unusual for a “box of bones” to be transported to Green-Wood. These were bones that could not be identified to a specific individual. But typically they wound up interred in the Green-Wood lot of the church where they had initially been interred–not in a family lot. This “box of bones,” removed from North Dutch Church and interred in the Robertson Family Lot on June 11, 1862, clearly was associated with this particular family. Could these be the bones of Archibald Robertson?

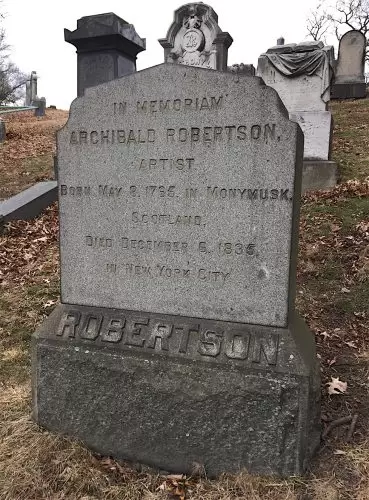

Having reviewed Theresa’s research, I proceeded to the Internet to see what I might find about Archibald Robertson and his interment. And there I struck pay dirt with a Find-A-Grave entry for him, which showed this stone:

Two matters are apparent here. One, the inscription on this stone matches in all details–name, occupation, date and place of birth, date and place of death–the artist we are looking for. Second, the inscription begins with “In Memoriam.” This is, in effect, a statement by the family that Archibald Robertson’s body does not lie there–or at least not his intact remains.

Given all of this information, the conclusion is apparent: Archibald Robertson, artist, is interred at Green-Wood–or at least the “box of bones” that likely contains his remains is. It seems likely that, in digging up three bodies, one of them was already out of its casket (perhaps from earlier disinterments from the churchyard) or then came out of its casket–so that the remains that were transported from the North Dutch Church to Green-Wood in 1862 were two identified bodies and a “box of bones.” Because this was well before DNA testing, there was no way to definitively determine that those bones were the remains of Archibald Robertson. But, because Archibald Robertson’s family is interred in this lot, it appears–based on the factors discussed above–that his remains–little more that a “box of bones”–are there also, with a granite stone dedicated to him, “In Memoriam.” Though Green-Wood’s records do not reflect the interment of Archibald Robertson, artist, it does appear that what remained of him–sadly no more than a “box of bones”–was interred at Green-Wood on June 11, 1862.