570,000 people are interred across Green-Wood’s 478 acres. Essential to the cemetery’s business is keeping track of each of these burials–and places for future interments. For each interment, there are likely multiple documents from many archival sets recording relevant information.

One of the sets in Green-Wood’s archives is its blueprints. Formerly housed in the cemetery’s surveyor’s office, they were transferred by Tony Cucchiara, Green-Wood’s archivist, to our archival storage area a few years ago. About 10 years ago, we were fortunate to have an architect, Gabriella Karl, volunteer to catalogue the blueprints. When she left Green-Wood, other volunteers continued her work.

It is inevitable, given the sheer volume of paper in Green-Wood’s archives, that filing mistakes are made. Fortunately, misfiling is a mistake that can be corrected.

But, before we get to that, let’s give you, dear reader, some context. The back story:

Charlotte Canda received the finest of educations; she was fluent in five languages: English, French, German, Spanish, and Italian. On February 3, 1845, a party celebrated Charlotte’s 17th birthday. When the festivities ended, Charlotte and her father got into the family carriage and escorted one of her friends home. With a storm raging, they arrived at the friend’s home on Waverly Place in Manhattan, and Mr. Canda walked the friend to the door. When he turned back, the carriage, with Charlotte in it, was nowhere to be seen. Racing home in a panic, he soon discovered that the horses, spooked by thunder and lightning, had bolted and raced towards Broadway. As the carriage careened around the corner, Charlotte was thrown from it and struck her head. Her parents were summoned as she lay wounded; they cradled Charlotte in their arms as she sighed her last breath and passed away.

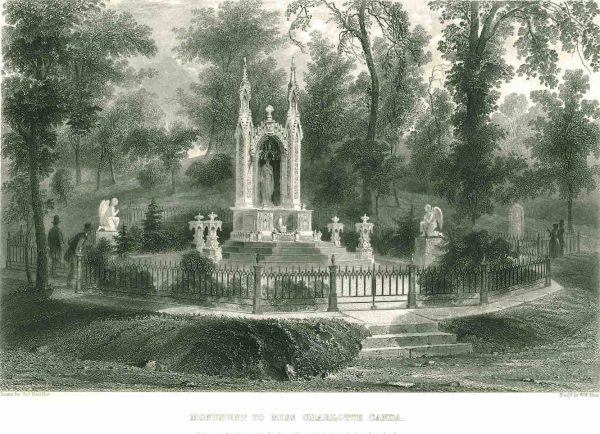

Within days, Charlotte was interred at New York City’s Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral at Prince and Mott Streets. Soon plans were made to reinter her at Green-Wood beneath an elaborate memorial. The starting point was a sketch that Charlotte herself had made as a proposed memorial for her recently-departed aunt. The monument, with the exception of the two winged angels (one to each side, imported from Italy), was executed by John Frazee (1790-1852) and Robert Launitz (1806-1870). Launitz chiseled the effigy of Charlotte. Her mortal remains were removed from the St. Patrick’s graveyard and were interred at Green-Wood on April 29, 1848, just three years after her death.

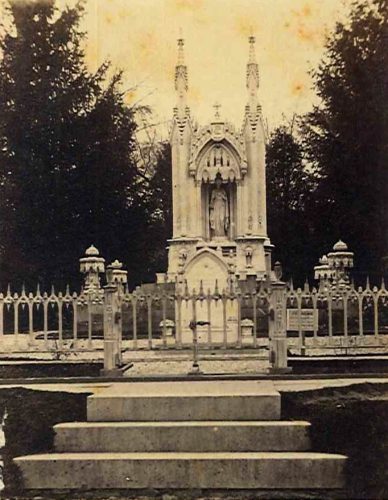

Here’s the memorial that sculptors John Frazee (who is himself interred at Green-Wood, with a rather mundane gravestone–particularly for a sculptor) and Robert Launitz created:

Charlotte’s father added to the plan the roses, a variety of flowers, birds, and wreaths, all of which his daughter loved. Also incorporated into the design were fleurs de lis (a reference to Charlotte’s French heritage), lilies, acanthus leaves, down-turned lit torches (symbolic of a family in mourning, but one in which the family line continues) and a crucifix. Carvings of the books that she loved, the musical and drawing instruments that she used, and the parrots that were her constant companions, were all incorporated into the design. Charlotte’s life-sized effigy appears in the niche; she is about to expire, with the heavens above waiting to receive her soul (depicted as a butterfly). To commemorate her age at death, 17 rose buds appear in a shield, 17 roses compose the wreath atop her head, and her monument is 17 feet high and 17 feet deep.

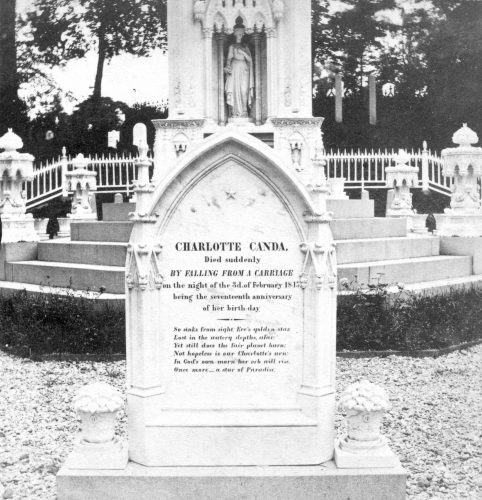

This monument was tremendously expensive for its time–estimates made soon after its unveiling, translated into 2018 money, would put its cost between $475,000 and $1.4 million. And it was tremendously popular–by all accounts it was the most-visited cemetery monument in New York, and perhaps in all of America. Crowds, aware of the tragic story behind it, gathered on the roads nearby, taking in the magnificence of this marble work. The lot was immaculately kept, surrounded by a white-painted cast iron fence, with white pebbles between the fence and the marble memorial. A marble slab stood upright just inside the fence gate, describing the tragedy of Charlotte Canda to all who came by:

The inscription reads:

CHARLOTTE CANDA

Died suddenly

BY FALLING FROM A CARRIAGE

on the night of the 3d of February 1845

being the anniversary

of her birth-day

A very Victorian poem about resurrection follows at the bottom of the slab:

So sinks from sight Eve’s golden star.

Lost in the watery depths afar:

Yet still does the fair planet burn;

Not hopeless in our Charlotte’s urn:

In God’s own morn her orb will rise,

Once more–a star of Paradise.

Unfortunately, this inscription is no longer readable–only a few letters and numbers from it have survived:

Here’s a photograph of the detail of the Canda Memorial, circa 1865:

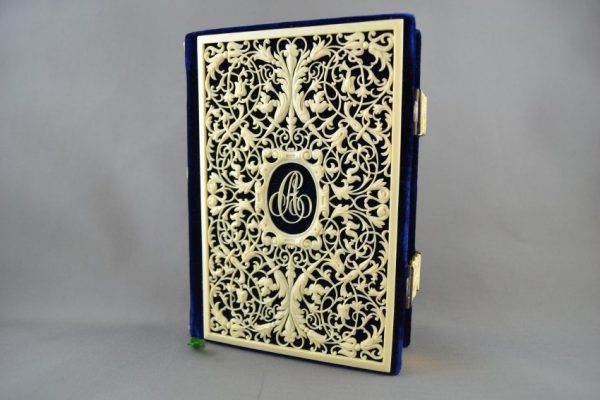

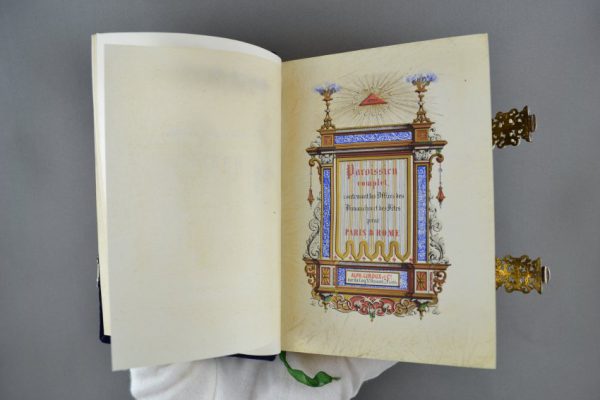

About 15 years ago, a Canda descendant donated Charlotte’s prayer book to Green-Wood. It is a spectacular piece:

Now back to the recent past. Just a few weeks ago, Green-Wood’s manager of historical collections, Stacy Locke, found these gems, which had been misfiled in our blueprint archives:

Stacy describes her find:

I had seen the sketches years ago and admired their beauty, but never knew what they were of. When browsing scans of architectural drawings of the Cooper/Hewitt lot, they once again caught my attention. Not only did they seem out of place amid the other drawings in this particular folder, I could not remember ever seeing a reference to something this ornate on the Cooper/Hewitt lot . . . . In fact, they reminded me an awful lot of the Charlotte Canda monument I had been gathering images of just a few minutes earlier. What struck me first was the large “C” monogram on the drawing. There are a number of monograms on the Canda monument but they are usually a double “C” for Charlotte Canda. The rosettes on the drawings also recalled to me the rosettes on the Canda monument, specifically a row of flowers that encircles the head of the sculpture of Charlotte. I pulled out a number of stereoview photographs of the monument and examined them with a 20x magnifying jeweler’s loop. Though many of the specific details of the monument spires were difficult to make out in such a small photo, I became convinced that that they were designed after this drawing. I looked also at close-up images of the monument spires from a recent cleaning, and noticed that, although much of the upper portion of the spires had been lost to wear and/or damage over time, the basic design was still visible. I checked with Jeff Richman, Green-Wood’s historian, and Neela Wikremesinghe, Green-Wood’s manager of preservation and restoration, for their thoughts, and was pleased when both agreed that these had to be Canda sketches. Finally, another browse through the Cooper/Hewitt drawings and I came across an architectural drawing of the base of the Canda monument, clearly titled. It became evident that the two files must have been combined at some point.

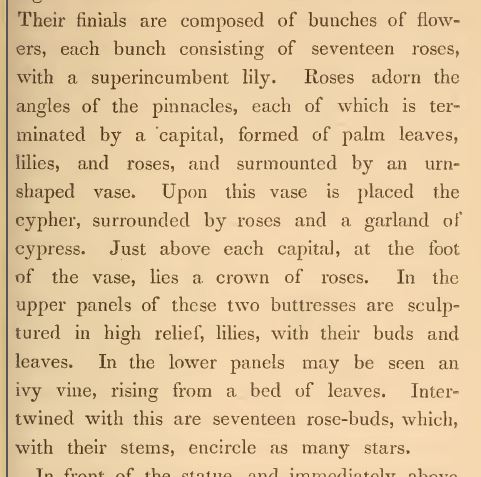

Nehemiah Cleaveland was Green-Wood’s first historian. Working for the cemetery, he wrote several guide books and self-guided walking tours in the 1840s, 50s, and 60s. Here is Cleaveland’s description of the finials shown above:

Roses were symbols, in the 19th-century rural cemetery, of a young woman who had died too young–who had not reached her full bloom. The effigy of Charlotte Canda, the centerpiece of the memorial, has her head crowned by a wreath of 17 roses–one for each year of her life. Here, the finials pick up on that theme, with crowns of 17 roses. Lilies are references to resurrection. Ivy is ever-green and therefore a symbol of eternal life.

Here is one of the finials, as it was carved. This photograph was taken circa 1860, just 12 years after the finials were unveiled:

Here are the finials, as they look today, recently cleaned by Green-Wood’s restoration team:

One final tragic note. The Candas were Catholics; their lot at Green-Wood was consecrated by a priest. Just off that lot stands the monument to Charles Albert Jarrett de la Marie. A French nobleman, he was Charlotte’s fiance. A year after her death, young Charles committed suicide at the Canda’s residence. Because of his “sinful” suicide, he could not be interred in the consecrated Canda Lot; rather, he was interred as close as possible to his beloved in an adjoining lot. His coat of arms is carved into his gravestone.