How is your Green-Wood eye? There have been a few subtle changes out on the grounds in the last couple of weeks. Here’s that story. Come visit and see for yourself!

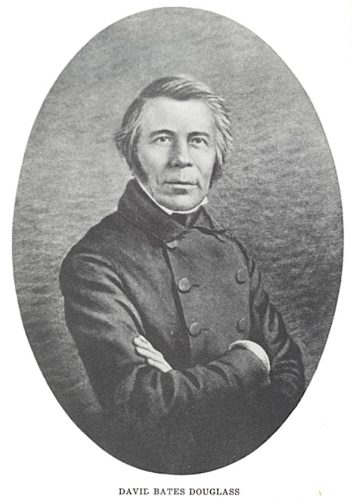

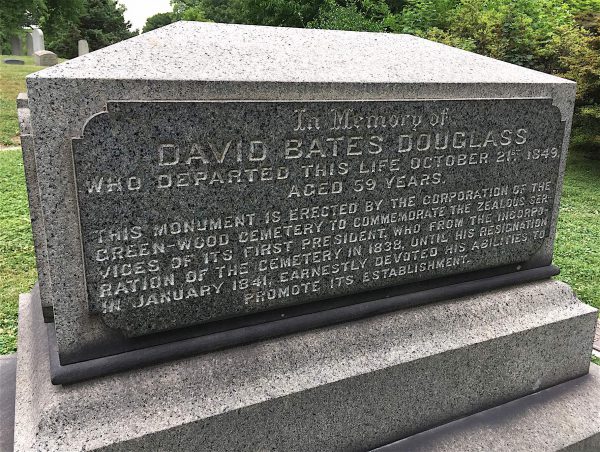

Several features of Green-Wood’s grounds date back to its initial design by engineer David Bates Douglass (1790-1849). A graduate of Yale, class of 1813, Douglass trained as a military engineer and served as a miner and sapper during the War of 1812. He later taught natural philosophy at West Point. Douglass was a fascinating, multi-talented man–he also took part the Cass Expedition of 1820, which issued reports on the plants, shells, geography, minerals, and Native Americans of the Michigan Territory.  Resigning from the military in 1831, Douglass worked as a civil engineer, designing canals and sewer systems. While teaching at N.Y.U., he was the architect of the collegiate building there (which stood on the east side of Washington Square Park). Douglass knew Brooklyn’s typography from his work on its railroads and sewers. After his work at Green-Wood was completed in 1841, he served as president of Kenyon College, designed rural cemeteries in Albany and in Quebec, and taught mathematics at Hobart College. He is interred at Green-Wood, in a lot donated by the cemetery to his family.

Resigning from the military in 1831, Douglass worked as a civil engineer, designing canals and sewer systems. While teaching at N.Y.U., he was the architect of the collegiate building there (which stood on the east side of Washington Square Park). Douglass knew Brooklyn’s typography from his work on its railroads and sewers. After his work at Green-Wood was completed in 1841, he served as president of Kenyon College, designed rural cemeteries in Albany and in Quebec, and taught mathematics at Hobart College. He is interred at Green-Wood, in a lot donated by the cemetery to his family.

When it came time for Henry Pierrepont to realize his dream–to bring a rural cemetery to New York–he hired Douglass (there was no such thing as a landscape designer back in the late 1830s) to do the design work. And it was brilliant! Douglass adopted the winding paths and roads that the English had introduced to rural cemetery design–no straight roads meeting at right angles here, unlike the first rural cemetery in the world, Pere Lachaise, outside of Paris. He cut the roads into the hills, leaving high banks along the avenues, so that the gravestones were at eye level for visitors–these memorials had been raised up, exalted.

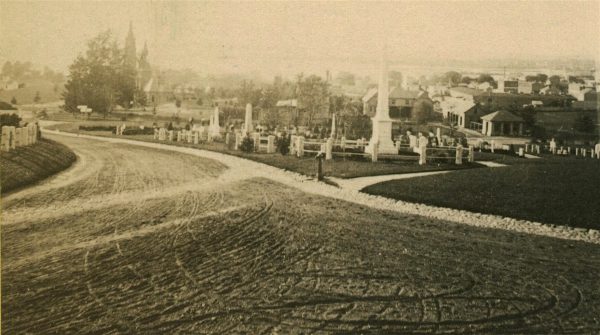

There was another important element to Douglass’s brilliant design: stone gutters along the roads. Farmers wanted flat land, free of rocks, with good soil in which to grow crops. Real estate developers wanted land that easy to build on: flat and free of rocks. On the other hand, Pierrepont and Douglass wanted glacial hills that were, by their nature, covered with rocks. That sort of land was cheap to buy–there was little market for it–but it would make visiting the cemetery an adventure because of its short vistas: a surprise, hidden by a hill, awaited the visitor around the bend–would it be an angel, an obelisk, or some other sculpture? So Douglass, working on the land on the Heights of the Gowanus that he and Pierrepont had picked out for Green-Wood, recycled the rock rubble from the terminal morraine, combing it off the hills to make the beds and gutters of the roads. The rock gutters would allow for drainage from the road surfaces–water would seep into the ground through the spaces between the rocks–while framing the road surface, giving it a broader look, and creating an apron for parking.

We have, in The Green-Wood Historic Fund Collections, several photographs of these gutters as they existed early in the cemetery’s history. Here are three:

Art Presson, Green-Wood’s superintendent of the grounds, explains his recent project to uncover some of Green-Wood’s old gutters, making them again visible to visitors:

It’s always interesting how things connect and then expand and grow at Green-Wood. This is one of those stories.

There was a European beech tree (planted around 1900) atop Battle Hill that shaded the Durant Mausoleum below it on Battle Avenue. That tree was removed recently, having succumbed to phytopthora (a soil born pathogen that infects trees and can cause their sudden death). Thomas C. Durant (vice president of the Union Pacific Railroad during its construction as the eastern part of the Transcontinental Railroad) lies in a mausoleum, built into the steep hillside slope that was in the shade of that beech tree. That slope had been planted as a shade garden in 2008, but once the tree was removed, it instantly became a full sun garden on the left side (the right side is still mostly shaded by an old cherry tree). As I thought about the best way to revise the garden, I took a few steps back to look more fully at the scene. It then occurred to me then that unearthing the old cobble gutter there would be a good edge for the garden and would allow us to feature one of Green-Wood’s historic landscape characteristics.

From the time of my arrival in 2006 as superintendent of grounds, I knew that Green-Wood’s president, Richard Moylan, was very protective of the cemetery’s old cobbled gutters. Faye Harwell, the editor working for the consulting firm of Rhodeside and Harwell on Green-Wood’s recently-completed Cultural Landscape Report, noted in that report that these gutters were indeed a defining element of our landscape and recommended that we uncover them where possible. So, I have recently focused on them.

Battle Hill is the most visited site in Green-Wood. Nearly every tour at least drives by that area, and most spend significant time there. There is so much worthy of visiting compressed into this small area. This made that area the perfect space for this demonstration project: removing several inches of soil that was atop the old gutters. To do that we utilized Green-Wood’s “Air Spade”– a high pressure compressor connected to a hose, with a very small nozzle that concentrates the force. That restricted nozzle creates pressure that easily cuts through turf and accumulated sediment.

Once the crew members got started, and quickly refined their technique, they didn’t want to stop. So, after they completed the gutter along Battle Hill, they went left on Hemlock Avenue, then left on Garland, and yet another left on Border Avenue up to the steps leading to the Civil War Monument, then back along Battle Avenue to the Durant Mausoleum–completing their work around the island that includes Battle Hill. It took a week for them to remove a truck load of turf and sediment. The gutter is still a bit dusty, but a few good soaking rains should clean the rocks up and finish the job.

Oh, and we have planted out the mausoleum garden; remember, that’s where this all started. At Green-Wood we regularly talk about the three legged stool–Art, History and Nature. We are at our best when those elements intertwine. From this garden you can take in the view of the recently-exposed cobblestone gutters, an artfully made mausoleum for a famous financier, the famous Battle Hill where once George Washington’s forces skedaddled north (fleeing British troops during the largest battle of the Revolutionary War)–and beyond that you can see the modern metropolis of Manhattan.

One final note: I was out on the grounds with Art two weeks ago, as the work uncovering the gutters around Battle Hill was being done. I showed him a more expansive version of the Kerr Lot photograph that appears above, this photograph in 3D, taken about 1870. Art put the red/cyan glasses I gave him on and went back in time a century and a half. Inspired by this view, Art sent his gutter-restoration crew out to the Kerr lot–and the gutter you see in the photograph above of that lot is once again visible.

Once again, visitors can enjoy one of the earliest elements of Green-Wood’s brilliant design–some of Green-Wood’s gutters–just as visitors would have seen them almost two centuries ago.