Green-Wood is a 19th-century (and 20th century and 21st century) sculpture garden. If you were alive in 1865, and wanted to see sculpture, Green-Wood was the place for you. Not the Metropolitan Museum. Not the Brooklyn Museum. Green-Wood!

Over the years, we have discovered prominent 19th-century sculptors whose works adorn Green-Wood’s grounds: Henry Kirke Brown, Charles Calverley, John Moffitt, and many more. Indeed, I have led several tours of their work. But, there are always more discoveries to be made.

I recently was working on pinpointing the location on the grounds of a marble bust of Mary T. Baldwin Norris. I knew this work from several stereograph photos in The Green-Wood Historic Fund Collections–photos dating mostly from 1865 to 1875. We have software at Green-Wood that allows us, once we locate the lot where a photograph was taken long ago, to translate that lot number into a GIS location. Then the techies at the Urban Archive app, with whom we are working, pinpoint the location of the relevant photograph on their map of New York City for visitors to explore. Stacy Locke, Green-Wood’s manager of historical collections, who has worked closely with Urban Archive, reports that 200 early photographs of the cemetery’s grounds are now accessible on the free Urban Archive app.

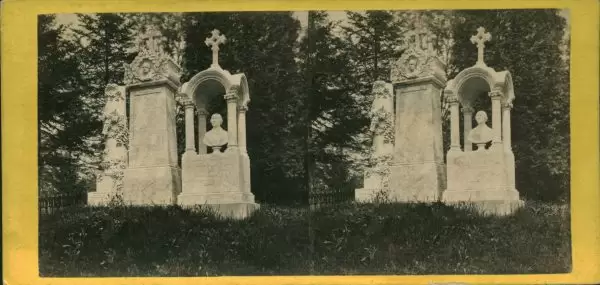

So, here’s the circa 1870 image I was working with:

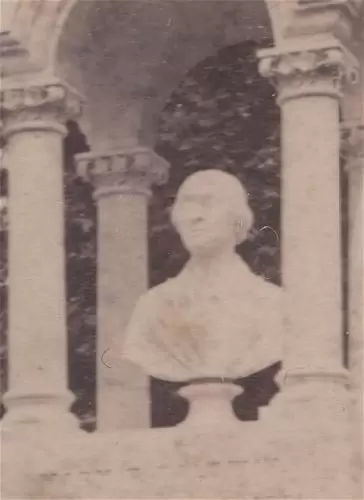

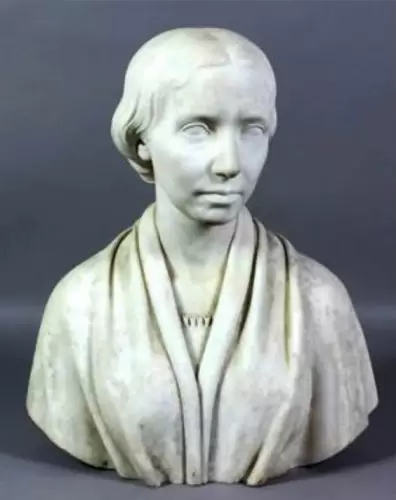

And here’s a close-up of the Mary Baldwin Norris bust, as it looked circa 1870:

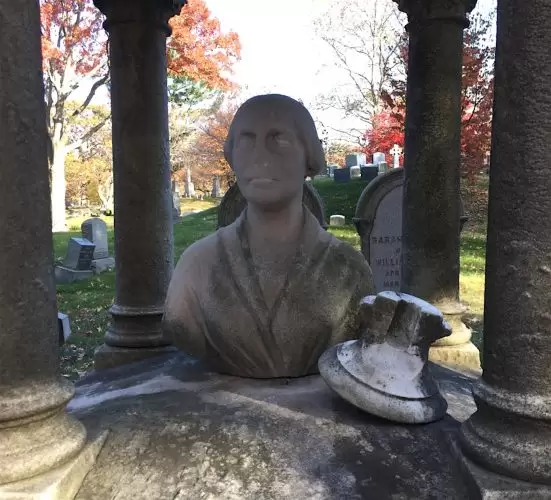

Looking at these images, I recalled that, years ago, I had discovered these monuments, still intact, along Dell Avenue. So I drove along that avenue and saw this:

I was able to determine that the above stereoview was taken in section 77, lot 1968–the Norris Family Lot. The label on the back of the card identifies the view as “Monument of Mary T. Baldwin.” That was her maiden name; her married name was Mary T. Norris (and that is the name under which her burial at Green-Wood is recorded). The lot is on the east side of Dell Avenue, between Central and Southwood Avenues, and is visible from Dell Avenue. Mary, as per Green-Wood’s records, was interred there on June 11, 1862.

As I examined the Mary Baldwin Norris bust, it was apparent that a repair had been done to the base supporting it. Checking with Neela Wickremesinghe, Green-Wood’s manager of restoration and preservation, I learned that she and her team had come across this monument in the fall of 2016, when it was in need of repair and looked like this:

Neela and her staff brought the pieces–bust and base–down to their Restoration Studio. There, the remnant of the base was used to create a mold and the mold was then used to cast a new base. Here’s the new base, in the studio, attached to the bust:

In August of 2017, the bust, with its new base, was re-installed in the Norris Lot, attached to its platform with two stainless steel pins and mortar, then pointed into place. Here it is, back where it belongs, exactly where it has been for a century and a half:

I wanted to take a closer look at the bust; perhaps there was a sculptor’s signature or a date on it. Here’s what I saw on the back of the Mary Baldwin Norris bust:

This name, J.T. Hart, did not ring a bell–I had not heard of a sculptor by that name. But an Internet search turned up a great deal of material about one Joel Tanner Hart, a 19th-century sculptor. No other sculptor matches this “J.T. Hart” signature. And, for reasons detailed below–similarity of signature on another work known to be by Joel Tanner Hart, stylistic similarities to other works by him, and the dates of his career, he’s our man!

Joel Tanner Hart was born in 1810 in Kentucky, into a wealthy family. But his parents soon lost their fortune and Joel, after completing just 3 months of school, was forced to end his formal education and to go to work as a mason, mostly building chimneys. His older brothers educated him and he diligently read nightly by the light of a wood fire. In 1830, at the age of 20, he got a job in a stonecutter’s yard in Lexington, Kentucky. He soon developed a reputation for carving gravestones. Ambitious and artistic (he also studied painting), Hart moved on to sculpting, creating a portrait of of the prominent Kentucky abolitionist Cassius M. Clay–and soon had great success. A bust of Andrew Jackson, sculpted by Hart from life at Jackson’s home, the Hermitage, in 1838, was sold to the ex-president.

Hart traveled outside Kentucky, was hailed for his work, and soon began to sculpt Henry Clay, from life, starting in 1846 and completing that work years later. That sculpture is signed “J.T. Hart”–the same signature that appears on the Mary Baldwin Norris sculpture at Green-Wood. Then Hart was off to Europe, setting up his studio in Florence, Italy, then spending 14 months in London studying anatomy. Widely hailed in Europe and in the United States, Hart received many commissions for marble busts. Though critics were mixed on the quality of Hart’s sculptures, sculptor Hiram Powers hailed Hart as “the best bust-maker in the world.”

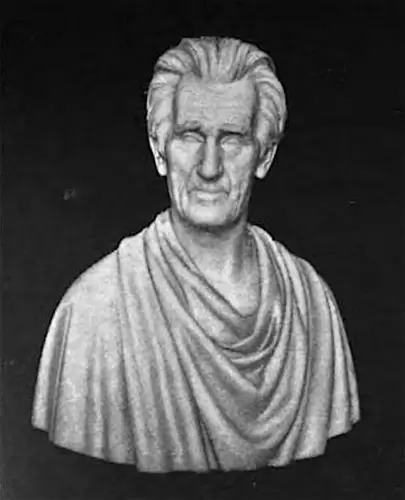

Here is Hart’s sculpture of Henry Clay, dating from 1865, as it appeared on the grounds of the Virginia State Capitol in the 19th century:

Hart died in Florence in 1877; his remains were brought back to Frankfort, Kentucky, ten years later, and he was interred there.

Hart sculpted the marble portrait of Theodore Parker (1810-1860) a Unitarian minister, transcendentalist, abolitionist, and reformer, which stands in the English Cemetery in Florence:

Here is Hart’s signature at the bottom of his Parker portrait:

This sculpture of a woman is signed by Hart and dated 1857–just a few years before he sculpted his similar portrait of Mary Baldwin Norris:

Green-Wood is indeed a great sculpture garden. We now have discovered one more piece of that story: that the sculptor, Joel Tanner Hart, is represented at Green-Wood with his marble portrait of Mary Baldwin Norris.

* * *

Thanks to Neela Wickremesinghe for sharing her restoration report and photographs. Great job!