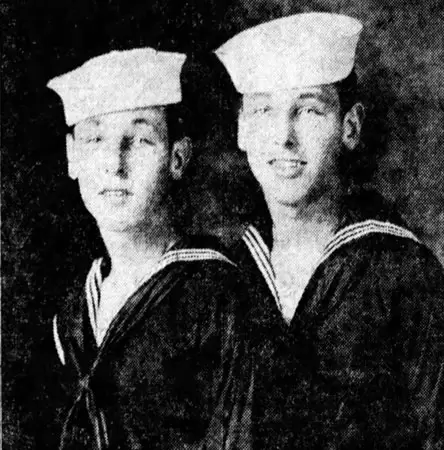

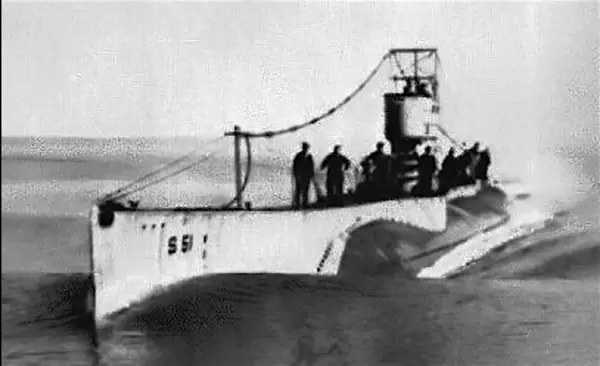

On September 25, 1925, a United States Navy submarine, the S-51, left New London, Connecticut, for a regular training voyage. The crew was 36 men; among them were the 19-year-old Teschemacher twins, William and Frederick, from Bangor, Maine.

All was quiet as the S-51 cruised on the surface, in the dark, on a “reliability run” 12 miles east of Block Island, Rhode Island. Her running lights were on. Most of the crew, including the Teschemacher twins, were in their bunks, asleep. The commanding officer was in the control room when the watchman on the bridge spotted lights in the distance, about 5 miles off; it was the merchant steamer City of Rome.

Because the S-51, by the rules of the sea, had the right of way, it continued to proceed with its course and speed unchanged. Meanwhile, the lights of the City of Rome grew closer. Then it was right there, looming over the S-51, on a collision course. Despite the submarine’s desperate last second maneuver, rudder hard right, and the City of Rome‘s efforts to turn and back its engines, the ships collided. A jagged gash was cut in the S-51’s sleeping compartment on the port side. The City of Rome then ran over the top of the S-51, driving her below the surface. With a tear about 30 inches wide in the S-51, the sea rushed in. Within a minute, the S-51 began its plunge of 132 feet to the bottom.

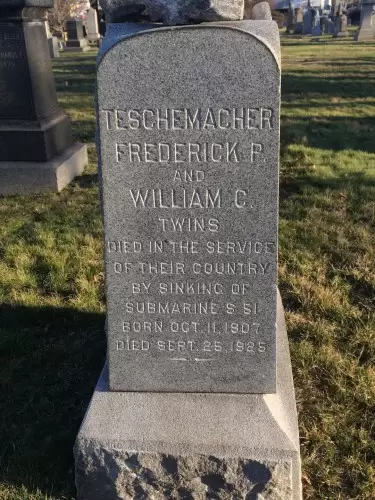

So what does this have to do with Green-Wood Cemetery? Well, just a few weeks ago, Marge Raymond, a leading Green-Wood tour guide, was taking a group through Green-Wood on our regular Wednesday afternoon tour. Marge, who is “always looking for something new,” glanced over and noticed this gravestone for the first time, brightly lit by the sun:

Even if you have been across Green-Wood’s grounds many many times, you know that there are always new discoveries to be made. Sometimes its a change in the light, sometimes its a slightly different route. But there is always something out there that you haven’t seen before, no matter how many days you may have spent wandering. So it was with Marge and this granite stone.

The Teschemacher twins, like most of their shipmates, had been trapped inside the S-51 as it sank. They had had no chance to save themselves. Of the crew of 36 men, only 3 survived. Those three spent an hour in the water, then were rescued by a small boat that happened to pass by.

Frederick P. and William C. Teschemacher had both attended Bangor High School in Bangor, Maine. After their freshman year, they had enlisted in 1922 in the Navy together after being promised that they would serve side by side. Sadly, they died together. William’s body was found by divers within a few days of the sinking. He was interred in section 184, lot 24871 at Green-Wood on October 8–just 13 days after his death. Unprecedented salvage operations (no submarine had ever been brought up from that deep), heroically undertaken by Navy divers, continued into the summer of 1926, when the S-51 was finally brought up and towed to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

But Frederick Teschemacher’s body was never found. Ultimately, the ship was sold for scrap. A court ruled that both the City of Rome and the S-51 had contributed to this disaster–the former for its failure to slow down and change course, the latter for having improper lights.

Now a stone marker to the Teschemacher twins stands at Green-Wood. It marks the final resting place of one, William, and is a cenotaph in memory of the other, Frederick. Born together, they died together.

Thanks to Marge Raymond for all of her work on, and sharing of, this story.

Great story! Thank you for sharing.

Thank you very much for an accurate account of the story of the Teschemacher Twins. Their mother, is my Great Granmother and I have been named in their honor. I am Frederick William Teschemacher and together with my brother Jack, we brought much happiness to her seeing the two of us, her Great Grandchildren, brought happiness to her in her final years.

If family members wish to reach out to me, I can be found by contacting me at drteschemacher@gmail.com.

Again, many thanks to you Marge Raymond and the reflection of sunlight on the gravestone that day.

Frederick William Teschemacher, Jr.