One thing leads to another, then another, and another. This story has just come together, in time for Black History Month.

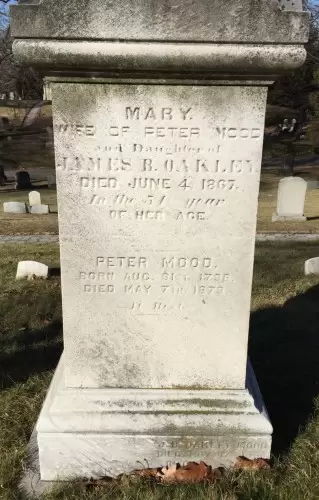

Just a few weeks ago, Sue Ramsey, who lives out in Santa Barbara, California, but by the miracle of the Internet is an esteemed researcher for Green-Wood’s Civil War Project, was doing follow-up research on Sergeant James Mood of the 13th New York State National Guard, who is interred at Green-Wood in in section 12, lot 7656. Mood died during the war, in 1864, when he was only 22 years old, while in the service of the United States. Because Mood died so young, there was very little information Sue had been able to find about him and his short life. But, as Sue noted, she had discovered something interesting about James’s father, Peter Mood, Jr., who is interred at Green-Wood with his wife Mary, son James, and other members of his family: Peter worked as a silversmith in Charleston, South Carolina, with his brother John, then moved to New York City. As per Sue’s note, there were “many examples of their work on auction sites . . . . Just thought I’d let you know in case you’re collecting artisan names.”

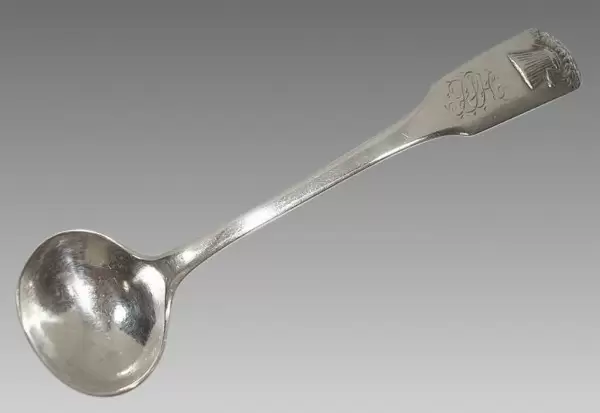

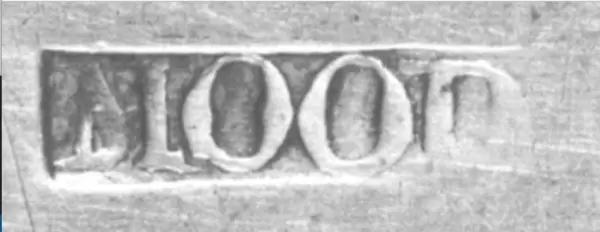

I do indeed collect the names–and life stories–of artisans who are interred at Green-Wood. So I searched the Internet for what these silversmiths had produced. Online, as expected, were photographs of silver gravy boats and spoons.

Peter Mood, Jr., and his brother John, were both trained as silversmiths in Charleston, South Carolina, by their father, Peter Mood, Sr. (1766-1821).

The brothers were partners, in Charleston, at the Sign of the Crossed Spoons, through the 1830s. They advertised themselves as “Wholesale and Retail Dealers and Manufacturers of Silver and Gold Ware.” In 1841, after their entire stock was stolen by an employee who had gotten their head clerk drunk and stolen the key to the shop from him, Peter left Charleston for New York City. Interesting, but not all that intriguing.

But then, continuing my online search, I came upon a link to something else—excerpts from a book—and we were off and running!

The book, published in 2004, is Slave Badges and the Slave-Hire System in Charleston, South Carolina, 1783-1865, by Harlan Greene, Harry S. Hutchins, Jr., and Brian E. Hutchins. It tells quite the tale of Peter and John Mood, Charleston silversmiths.

As explained in the book, Charleston was unique for cities in the South: only it required slaves who were hired out by their owners to carry a slave badge at all times. Slaves who did not visibly wear a badge were subject to arrest, jail, and fines. A slave would be hired out when his owner did not have sufficient work to keep him busy; the slave would then pay his owner an agreed-upon part of his or her wages, and would keep the rest.

Each year, starting in 1783, Charleston sought bids for the manufacture of the slave badges for the upcoming year. Artisans, hoping to supplement their income, would bid against each other. In 1835, one of the years Peter Mood, Jr., and his brother John had the contract to make all of Charleston’s slave badges (the other year they had the contract was 1832), they were paid $199.50 for their work. Approximately 3,500 badges were sold by the city that year; income from their sale was about $7000, or $2 per badge, on average. The badges were not silver; rather, they were made of copper or tin.

Now the plot thickens. Peter Mood, Jr. was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1796, to Peter Mood, Sr. (1766-1821), and Mary Dorothy Mood (1756-1819). As per the 1820 census, he was living in Charleston and owned 5 slaves. In 1837, he married Mary Oakley in New York City. This is interesting–why would they have been married in New York City rather than in Charleston, his lifelong home? We do know that there was much travel between Charleston and New York–their economies were intertwined, because much of the South’s cotton crop was sold through New York City dealers. In any event, after the looting of the Mood brothers’ Charleston business in 1841, Peter and his family made the move to New York City. The next year, his brother John reported: “Peter has gone north. He would not be persuaded on any terms.”

Slavery had been outlawed in New York State in 1827–so Peter left the system of slavery and the slaves he owned behind when he and his family moved north. According to the 1855 New York State census, Peter, in just 14 years, already was well established in New York City: he was in the fancy goods business at 72 Hudson Street in Manhattan and was living in a brick house there worth $15,000 (a large sum of money back then, equivalent to $400,000 today) with his wife, five children, and a domestic servant from Ireland. According to Internal Revenue Service records for 1865, Peter Mood owned 45 ounces of silver plate on which he owed a tax of $2.25. In 1868, he was living at 61 Morton Street in Manhattan; by this time, in his early 70s, he apparently was no longer working.

Meanwhile, back in Charleston in 1841, John Mood, with both his stock and his brother/partner gone, determined to restart his silversmith business, by himself, “with no capital but an honest name, skillful hands, and an abiding trust in God.”

Brother John had been born a Lutheran, but had converted to Methodism. He became a Methodist minister, at a time when many Methodists were opposed to slavery, and he prayed over the issue of slavery. Determined to do right, he chose to violate the strict laws of South Carolina and teach black Methodist ministers to read and write. In 1832, the very year of one of the contracts he and his brother had won to make Charleston’s slave badges, he established a Sunday school for black children and ran it by himself. Despite threats, including tarring and feathering, he persisted in his teaching. He also seems to have taken an active role against slavery in other ways: his son, in a family history, told the story of how he and the Rev. Mood were walking in Charleston one day when they saw an African-American, about to be auctioned off, make the secret Masonic sign of distress; John sent his son to get others to help him buy the man, ostensibly to set him free. John Mood’s father-in-law, Alexander McFarlane, was similarly engaged in anti-slave activity: he died in Sierra Leone, Africa, while working with former slaves to return them to freedom. John Mood is interred at Bethel Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina.

So, for Black History Month, I share this story with you, a story related to both slavery and freedom. Two silversmiths in Charleston, South Carolina, making slave badges; one who put himself in danger to teach Charleston’s African Americans the strictly forbidden abilities to read and write, the other who chose to leave a slave economy and sacrificed his son during the Civil War in the Union’s fight for freedom and the end of slavery.

I am a descendant of John Mood. One of our family members, Mac Stubbs, did a family history of the Moods of Charleston. Henry Mood, John’s son did in fact teach the Black Sunday School class at Bethel Methodist Church on Calhoun St. in Charleston. There was a fairly sizable free black population in Charleston before the Civil War and blacks attended Bethel both as free and slaves although segregated within the church. There had been schools for the sons of free blacks in Charleston but following the Vessey slave rebellion, laws were put in place requiring supervision by a white. Henry was requested to start a school for the free young black men and Henry was wanting to attend the College of Charleston which was nearby. His father had had to declare bankruptcy after a theft of sliver from the shop so this was a way he could make the money for college. i don’t know about being tarred and feathered and the school while looked down upon was legal in fact since many of the free blacks in town were skilled artisans it was fairly profitable for him. Four of the five Mood boys used the school as a means to fund their education at the College of Charleston, teaching the school in the afternoon after having attended the College of Charleston during the day. All of the four became Methodist ministers. The fifth brother became a doctor. Henry later became president of Columbia Women’s College in Columbia, SC and the second brother, Frances Asbury Mood moved to Texas where he became President of Southwestern College in Georgetown, Texas.

As an aside, the College of Charleston was also the alma mater of John C. Fremont who was the first Republican candidate for President of the US. Fremont was known as the “pathfinder” for his expeditions in the far west with Kit Carson. He was instrumental inv the conquering of California during the Mexican American War and was a Union General during the Civil War.

Mac Stubbs, the family biographer, questioned whether Peter Mood’s father in law, Alexander McFarlane, was helping free slaves or was he involved in the slave trade when he died off Sierra Leone. I also wonder how Peter, Jr ended up with so much silver in New York when the shop had been looted and Henry ended up bankrupted.

Thanks, Bill, for sharing this information. It is very interesting!

I am directly descended from John Mood. Thanks for all the info and research put into this. It really shows the difference between making money by taking advantage of the way things are, and making a living by doing what’s right.

On a side note, thanks to cousin Bill Neely for the additional info.

I would love to know more about Johann Peter Mood, Peter Sr.’s father if available

Is there a link of the Moods then in Peter Moods time, and the Moods now of the negro race. Did Moods own a plantation or birthed any children from slaves, or give slaves the Mood name?

I do not know the answer to your question. My research did not extend to that issue. That research can be done by a professional genealogist–