The year was 1828. They were in love. Charles Alfred Baudouine was 20 years old, Ann Phillips Postley 15. Five years later–in 1833-they would marry. She would die, “after a lingering illness,” in 1890. He would die in 1895. They are interred, together again, at Green-Wood, in section 14, lots 11608-11611, with many other members of their family.

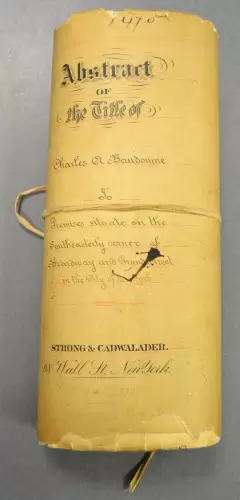

Green-Wood recently purchased at auction a book and real estate deeds pertaining to Charles and Ann. The book starts with this calligraphic title page:

The album contains 68 pages of poems and sentiments, addressed to Ann and written primarily by Charles, dated from late 1828 through 1833–but also poems and inscriptions by other Baudouines and Postleys, as well as their friends. Poems have titles very much of the time, the early 19th century, such as “It is Good to be Merry and Wise,” “The Hour of Prayer,” “A Woman’s Heart,” and “The Last Rose Of Summer.” The album features 6 small but skillful watercolors by Charles, as well as text and other drawings by him, many of them specifically dedicated to Ann. For instance, there is this:

Let not a line be wrote in vain,

On pages pure, there to remain,

May every thoughful verse contain,

Lively melody’s enchanting strain.

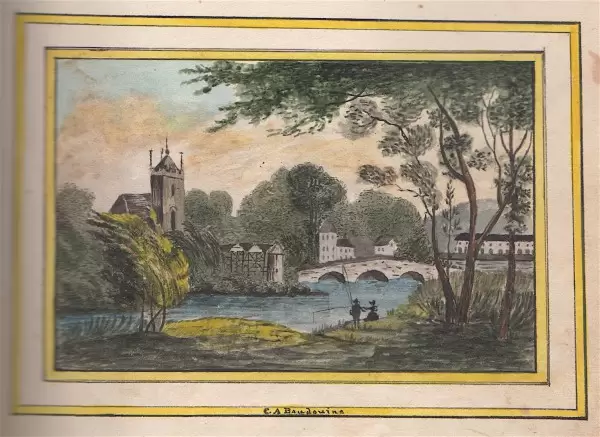

The album includes a total of six small watercolors, each signed C.A. Baudouine. Here is one of them:

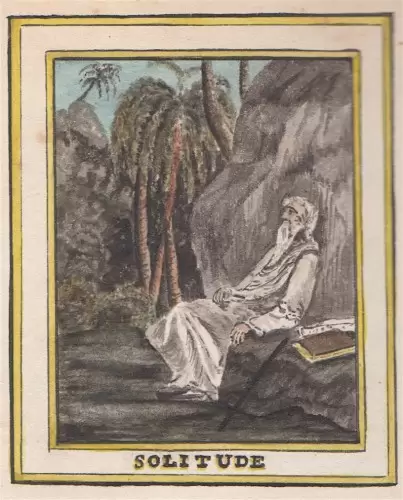

This illustration, by Baudouine, is entitled “Solitude:”

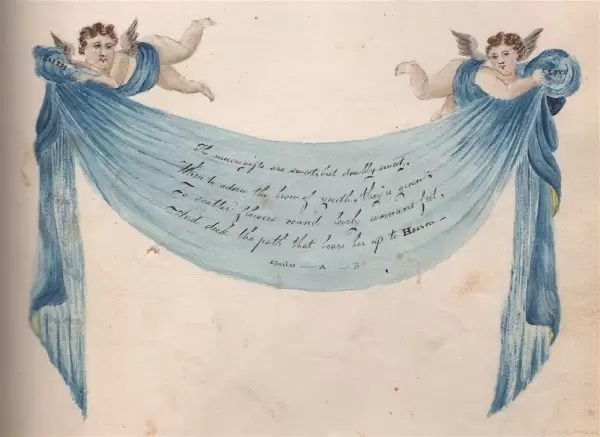

This work of art by Charles Baudouine appears in the album:

The muses gifts are sweet but doubly sweet,

When to adorn the brow of youth they’re given,

To scatter flowers ’round lovely woman’s feet,

And deck the path that bears her up to Heaven.

Also included our purchase is the deed, dated 1879, for Charles Baudouine’s furniture store at the southeast corner of Broadway and Grand Street in Manhattan:

So who were Charles and Ann? Charles Alfred Baudouine was born in 1808 in Manhattan. Charles was a cabinetmaker; in 1829, after having completed his apprenticeship, at the age of 21 he opened his own small furniture-making shop at 508 Pearl Street in Manhattan with $300 from his wife Ann (who owned a millinery shop nearby). On Monday evening, June 3, 1833, Charles and Ann were married at the First Baptist Church, as reported by the New York Evening Post. He moved his business to 332 Broadway in 1839.

In 1840, Cyrus Field, a very wealthy New Yorker who would go on, in the 1850s, to be the lead financier of the Transatlantic Cable (which briefly, in 1858, allowed telegraphic communication between America and England, before it failed), hired Baudouine to furnish his new Gramercy Park townhouse. This marked the first time in New York City that a professional had decorated a private residence. Baudouine: New York’s first interior decorator! Charles was a multi-talented artist: he could draw, make furniture, and decorate.

In 1845, Charles moved his furniture business to 351 Broadway and in 1849 to 335 Broadway (at what is now its corner with Worth Street). His business was huge: he had 200 men working for him, including 70 skilled cabinetmakers, as well as carvers, varnishers, and upholsterers. By the 1850s, Baudouine was considered the top furnituremaker in New York City. His workers were masters of the Rococo Revival. As Ernest Hagen, who worked for Baudouine, described that business in his Personal Experiences of an Old New York Cabinet Maker:

The work produced in his establishment consisted mostly of the gaudy, over ornate, carved rosewood furniture, although some oak dining room furniture was made, all in French carved style with bunches of fruit and game hanging on the panels. But very little mahogany was at that time made in his shop and no walnut. . . . This furniture was all the style at that time amongst the wealthy New Yorkers.

Hagen, an expert in such matters, characterized Baudouine as “the leading cabinetmaker of New York” and, by another account, Baudouine’s establishment was “the largest of its class in the country.” Indeed, A Stranger’s Guide in the City of New-York, published in 1852, recommended that tourists visit Baudouine’s shop; it was “one of the greatest attractions in the City.” Baudouine himself described his establishment as having “constantly on hand the Largest Assortment of Elegant Furniture to be found in the United States.”

Of Huguenot descent, and fluent in French, Charles regularly traveled to France to buy supplies, including upholstery, hardware, and trim. He brought French furniture back with him to sell in his shop, side-by-side with his own pieces. Baudouine retired in 1856 and lived at the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 56th Street, driving a coach pulled by four horses, and continued to have a substantial income.

In 1865, Charles reported to the Internal Revenue Service that his annual income was $21,711 (the equivalent of $312,000 in 2017). He was a wealthy man, owning 5 carriages, a watch, a piano, a billiard table, and 2 pounds of silver.

Upon his death in 1895, Baudouine left a fortune estimated at between $1.4 and $5 million (which, in 2017 money, is between $38,000,000 and $138,000,000). After his retirement as a cabinetmaker, Baudouine had invested his substantial savings in real estate. He bought up small buildings on main thoroughfares, tore them down, and built large new buildings. His estate included 6 buildings on Broadway, three on Warren Street, one on West 55th Street, and three on Fifth Avenue. The Baudouine Building at 1181 Broadway (just south of 28th Street, on the west side of Broadway) was built around the time of his death, still stands, and is named for him. Not surprisingly, his family engaged in a heated battle, with much litigation, over his estate–providing fodder for years of sensational press coverage of various skirmishes.

I have run across the Baudouines once before at Green-Wood. In December of 2015, I posted a blog about William Pitbladdo, the monument maker, his account book, and the monuments he created that were installed at Green-Wood. In that blog post was this image and this caption:

I was recently driving around the cemetery, showing an artist around. When I came to this lot, I pointed it out as the Baudouine Lot–and as soon as I pronounced that name, I realized that this was the final resting place of Charles and Ann.

The purchase of these items: Ann’s album, so lovingly decorated by Charles, and the deeds and legal papers that relate to their large fortune–help us tell the fascinating story of two of Green-Wood’s permanent residents–and to better understand what makes Green-Wood so special. We are happy to have them!