Having come across many fascinating Green-Wood stories over the course of the last 30 years, I know that there is always one more just around the corner. And recently that was the case, when Mike Stalzer, on Instagram, shared the story of a “double suicide.”

This is one I had not heard of before. But it took only a few minutes of Internet searching for me to confirm this story—and to start to gather its extraordinary details.

Dorothea and Gladys Cromwell were twin sisters, born in Brooklyn in 1885. Educated at private schools in New York City, they then studied and traveled abroad. They were descendants of Oliver Cromwell and women of great wealth, each having inherited a fortune from their father, who served as a trustee of the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York City.

The twins were living together in an apartment at 535 Park Avenue when they volunteered, during World War I, to work in France, near the front at Chalons-sur-Marne and Verdun, for the Red Cross in a canteen and as nurses. Harriet Rogers, assistant head of the canteen, described the Cromwell twins as follows: “They are angels who not only do first-class work on day or night service, but also find time to visit the soldiers in the French hospitals and to befriend the little French refugee children. Everybody loves them and admires their efficiency and courage in real danger.”

In the Biographical Note to Gladys’s book of poems, published in 1919, their Red Cross work in France is described as follows:

For eight months they worked under fire on long day and night shifts; their free time was filled with volunteer outside service; they slept in “caves” or under trees in a field; they suffered from the exhaustion that is so acute to those who have never known physical labor; yet no one suspected until the end came that for many months they have believed their work a failure, and their efforts futile. . . . overwhelming strain and fatigue had made them more weary than they realized, and the horrors of conditions near the Front broke their already overtaxed endurance.

The Cromwell twins became celebrities in France. And they were happy to continue their work there, even after the armistice of November 11, 1918 had ended combat. But their only brother, Seymour, urged them, with the war having ended, to come home, and they relented, boarding the SS La Lorraine on January 19, 1919, at Bordeaux Harbor, for the voyage back to their home in New York City.

United States Army Private Jack Pemberton was on duty on the upper deck of the La Lorraine the night it started for America. As he huddled against a brisk wind and a cold mist, he saw two women, each wearing a black cape, walking arm-in-arm, talking. They then separated, and one of the women climbed atop the ship’s rail, then disappeared. The second woman followed, also climbing the rail and disappearing into the blackness. Pemberton heard two faint splashes below. He ran to the corporal in charge of sentries, who alerted the bridge, and the alarm was sounded. But it took 15 minutes, during which the ship traveled 5 miles, before the ship could be slowed. By that time the river channel was too narrow for the ship to turn around and search for bodies.

In New York, their brother, Seymour (who died in 1925 and is interred in section 70, lot 1792), who served as the president of the New York Stock Exchange, was unconvinced when word arrived of their deaths and the possibility that they had been suicides. He had received what he described as “a cheerful letter” from them just a week before they were to sail. Two days after the La Lorraine sailed, he had received a cable from the sisters stating that they had missed that ship and would be sailing soon on another ship. He had cabled French organizations for more information, but it had been slow in coming. When his inquiry to the shipping line was forwarded to the captain of the La Lorraine, the captain had cryptically cabled back that the sister’s baggage was in their state room, but they were not on board. But then came information that a note had been found in their stateroom, addressed to the head of their Red Cross unit, stating that they intended to “end it all.” Friends confirmed that both had complained of being tired, both physically and mentally.

Many witnesses aboard the Lorraine reported that one of the sister had been extremely unhappy. According to a report in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, four people on the Lorraine saw the sisters jump to their death. On January 26, The New York Times reported that the police commissioner of Bordeaux had confirmed that their deaths were by suicide.

It appears that the Cromwell twins, subjected to the horrors of war, ranging from shelling to dealing with the carnage of the injured and dead–had been the victims of shell shock, a term that emerged with the horror of World War I–what today we would call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Miss Rogers, their Red Cross supervisor, was quoted, in what certainly sounds a bit quaint and uninformed today, given what we know about PTSD and its impact on even the toughest of individuals, mistakenly attributing their shell shock to their “sympathetic” nature: “If they suffered a nervous reaction after the great need for effort was over, the same thing occurred to some of the best men in the allied armies. Such souls, who, besides giving their best in service, are too sympathetic to endure the sufferings of others, are entitled not only to our warmest sympathies, but our truest admiration.”

A memorial service was held at St. Bartholemew’s Church in Manhattan on February 5. Many Red Cross nurses in uniform and prominent society people attended.

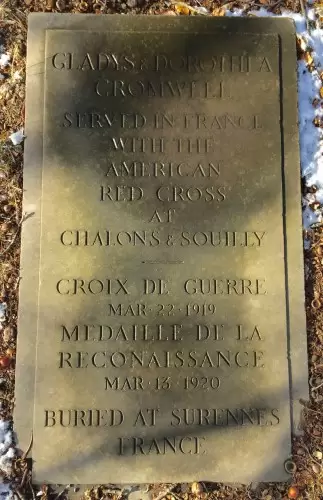

The bodies of Gladys and Dorothea Cromwell were recovered on March 20. Both Cromwell sisters were awarded France’s Croix de Guerre and were interred with military honors at Surennes American Cemetery, on a hill overlooking Paris, with full military honors. It is the final resting place of 1541 Americans who died during World War I and a place of remembrance for 974 Americans who were lost at sea as well as for 24 American soldiers who are “known but to God.”

Lovely cenotaphs to their memory adorn the Cromwell lot at Green-Wood.

Gladys Cromwell was a gifted poet. Her book, Poems, was published late in 1919, late in the year of her death. Padraic Colum, in the introduction, wrote that “the world was difficult for her . . . most of her poems are touched by a tragic vision of life.” Her poetry has been described as “deeply thoughtful and almost sculptural in its chiseled beauty. It shows the reaction of a finely tempered spirit to a world at variance with it.” This is her poem, “The Mould”:

No doubt this active will,

So bravely steeped in sun,

This will has vanquished Death

And foiled oblivion.

But this indifferent clay,

This fine experienced hand,

So quiet, and these thoughts

That all unfinished stand,

Feel death as though it were

A shadowy caress;

And win and wear a frail

Archaic wistfulness.

In his introduction to Gladys’s poems, Padraic Colum wrote about the Cromwell twins:

A year ago the soldiers in the Chalons section were speaking of herself and her sister (two beings indeed with a single soul) as “the Saints.” The government of France recognized their devotion and the worth of their service by the decoration it gave. These sisters were like twin spirits caught into an alien sphere, strangely beautiful and strangely apart, and the heavy and unimaginable weight of the world’s agony became too great for them to bear.

In October, 1919, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that each of the Cromwell sisters had left an estate of $661,748—the equivalent of just over $9 million in 2017 money.

The United States entered in World War I in April, 1917. In commemoration, 100 years later, I will be leading a World War I trolley tour of Green-Wood on Saturday, April 22. We will visit the Cromwell sisters’ cenotaph on that tour, and tell their story.

Fascinating!!! Many thanks for the info

Jeff,

I will be on a trip until the end of April and will miss the April 22 tour. Will there be another time to hear about the Cromwell sisters? Henry Miner

I will try to include them on upcoming tours. It is a fascinating story and wonderful memorials.

Amazing work, Mr. Richman!

Riveting that these twins gave so much, and lost everything. May God cradle their souls.

Thank you for this poignant tale – shell shock affected so many at the time but was overlooked and not treated as it would be today. I love the stories that lie behind a headstone and endeavour to bring these tales of people who are interned or remembered at Rookwood cemetery in Australia in my capacity as a committee member of the Friends and volunteer tour guide there.

The humblest headstone can reveal a tale of a most fascinating person.

Yes, there are many stories to be re-discovered–and told.

So interesting yet sad. Thanks for sharing their story.

Excellent research on a little known piece of history. Sad that we lost two angels, and our country was made better by their works.

My Granddaughter Katerina and I were visiting my parents grave across the street from the Cromwell Sisters. I took my Granddaughter up the knoll to show her the view when we saw the Cromwell Sisters Headstone. We found it interesting and shared our thoughts on how they were twins..born and died on the same days. This amazing story touched both my of our hearts. Thank you for your research.