Marianne Hurley is a landmarks preservationist with New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. She recently did a stellar job of researching and writing the Landmarks Preservation Report which led to the designation of Green-Wood’s Chapel and its Fort Hamilton Parkway Entrance as New York City landmarks.

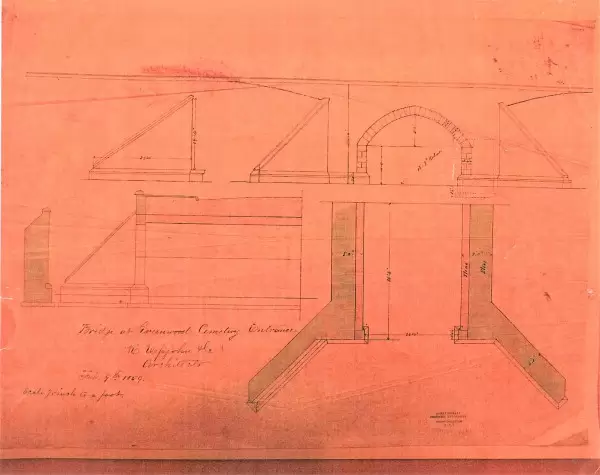

During the course of her research, Marianne came across this drawing of a bridge at Green-Wood:

I had never seen this drawing before–but I immediately recognized what I thought it might be: the bridge that supports the bed of Fifth Avenue as it crosses Martense Lane Pass. Martense Lane Pass is one of the few passes that allow east-west passage through Brooklyn’s terminal morraine–the hills left by the glacier as it went south, then retreated as the climate warmed. Martense Lane Pass was used by the British army of 5,000 under General James Grant to move west and turn north up the Gowanus Road during the Battle of Brooklyn on the morning of August 27, 1776. Here’s what the bridge looks like today:

It makes perfect sense that Richard Upjohn, the first president of the American Institute of Architects and the architect of Trinity Church at the head of Wall Street in Manhattan, would have designed this feature. Upjohn was Green-Wood’s go-to architect in its early years. He designed its Receiving Tomb early in the 1850s and, with his son, Richard Michell Upjohn, was the architect of Green-Wood’s Gothic Main Gates (build 1861-1863 and landmarked in 1966). Upjohn also created the Ladies Shelter which stood at the intersection of Southwood and Locust Avenues; it was made of wood which deteriorated badly over a century of exposure and was torn down about 40 years ago.

♦ ♦ ♦

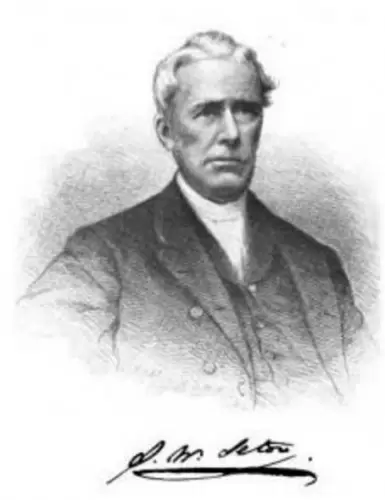

I recently heard from Michael Towers. He had come across the story of Samuel Waddington Seton (1789-1869), who devoted his life to the education of children.

Seton was born into wealth–his father was the first president of the Bank of New York, then the second banking-house in the country. But Samuel was left an orphan at an early age. Aided by John Jacob Astor, Samuel made a trading voyage to China. On his return in 1807, he went to work for the Bank of New York, and in 1823, he was elected by the Public School Society as a trustee of the schools. This launched a career in both public and religious education that would last for the rest of his life. As a young man, he had been engaged to be married, but his bride-to-be died just days before their scheduled wedding, and he remained single for the rest of his life. For many years he worked as assistant superintendent of New York City’s public schools. His love of education was such that, for the last 50 years of his life, he also ran the Baptist Church Sunday School–even though he was an Episcopalian! During those 50 years, he missed a total of 12 days of work. For the last ten years of his life, in his 70s and then his 80s, he walked every day from his home on Union Square to Harlem to visit and inspect the public schools there.

When Samuel W. Seton died in 1869, The New York Times wrote:

Mr. Seton belonged to that rare order of men who, without seeking notoriety or the applause of men, pursue the even tenor of their way through life faithful to one great idea, and that idea the doing of good to their fellow men. He devoted his long life to the promotion of public education and the moral and religious instruction of the young.

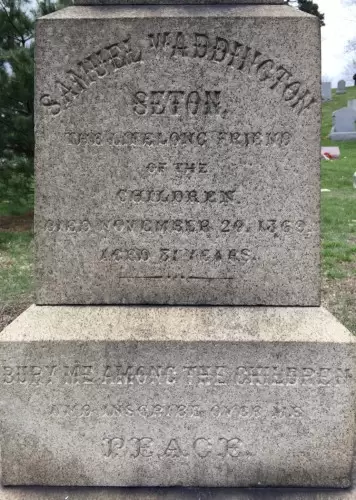

The information that Michael sent me about Seton included this note: “His grave is in the center of the children’s plot, in Greenwood Cemetery.” So I went out to section 121, lot 126, where Seton is interred–surrounded by the graves of children, many of which are unmarked:

Those children lie in lot 4781–sold in 1851 as an enclosed lot for children. The first burial in that lot occurred in 1857, and the last in 1870.

Samuel W. Seton made three requests before he died: that specified flowers be placed on his grave, that he be interred with the children in their lot at Green-Wood, and that his gravestone be inscribed “Peace.” It appears that all of these requests were granted.

The New York Public Library recently acquired Samuel Seton’s diary. You may read more about him and that diary here.

♦ ♦ ♦

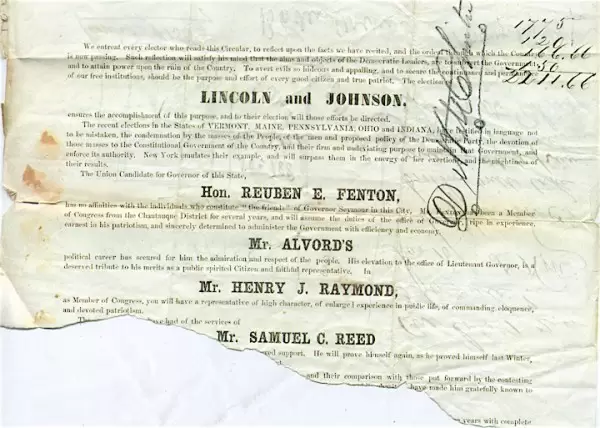

Green-Wood’s archives consist of millions and millions of records documenting the interments of 565,000 individuals. Historic Fund volunteers have been working for five years at archivally processing those records. During the process of that work, we have come across some great treasures. Here’s one–in our files because it was used as a piece of scrap paper:

This handbill was produced for the 1864 Presidential election–in the midst of the Civil War–for the Republican ticket. After noting “the ordeal through which the Country is now passing,” it accused the opposition, “Democratic leaders,” of aiming “to subvert the Government and to attain power upon the ruin of the Country.” The re-election of President Abraham Lincoln would “avert evils so hideous and appalling . . . .” Further down, the handbill endorses “Mr. Henry J. Raymond” for Congress as a “a representative of high character, of enlarged experience in public, of commanding eloquence, and devoted patriotism.” Raymond was a co-founder of The New York Times, its editor, and chair of the national Republican Party. Here he is:

Lincoln won his election for president; Raymond was elected to Congress.

♦ ♦ ♦

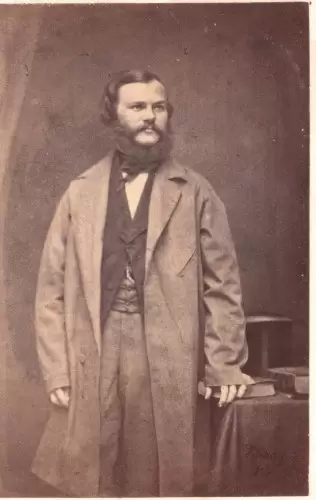

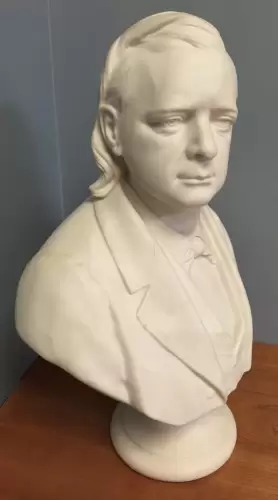

We continue to collect objects, photographs, and documents pertaining to Green-Wood and it permanent residents. I recently came across this Parian ware bust in an online auction:

The seller listed it without identifying the subject of this bust. But, to me, though the photographs in the auction listing were difficult to make out, it looked to be Henry Ward Beecher, who is interred at Green-Wood. Beecher’s fame has diminished severely since his death. During his lifetime, he was, as per the title of Debby Applegate’s recent biography of him, “The Most Famous Man in America.” That is pretty famous, particularly considering that one of his contemporaries was President Abraham Lincoln, a pretty famous man himself. Beecher, reverend of Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, was famous as a leading voice of abolition (he held slave auctions there to purchase the freedom of slaves and to dramatize slavery), as a moral leader (2,000 people attended services every Sunday to hear him preach), as a supporter of the fight for free soil (rifles sent to Free Soilers, who battled against slave interests in “Bleeding Kansas,” were known as “Beecher Bibles” in his honor–they were shipped in crates stamped “Bibles.” Lincoln personally asked Beecher to deliver the invocation at Fort Sumter on April 14, 1865, when the American flag was again raised over the United States fort against which the first shots of the Civil War were fired; Lincoln would be assassinated that night. And, Beecher was also the subject of the great scandal of the 19th century–sued by Theodore Tilton, whom he had mentored, for “alienation of affection” for the affair Beecher seems to have had with Elizabeth Tilton, Theodore’s wife. But, since Beecher’s death, he has become known largely as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s brother–she was famous in their lifetimes as the author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” but was, in their time, in no way as famous as he was. Times have changed.

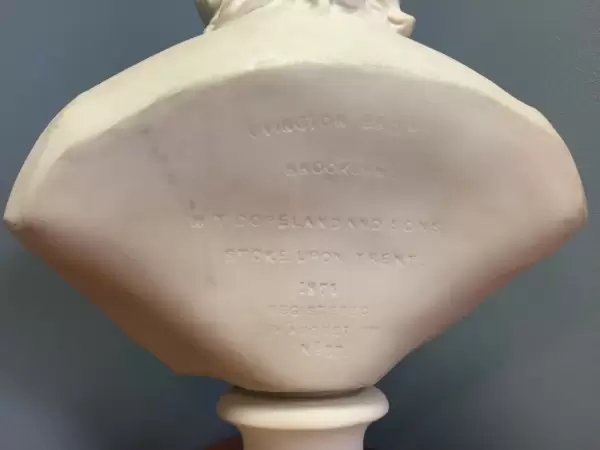

I had come across this piece not because it was listed as of Beecher–the seller apparently had no idea–but because it was listed as imported by the Ovington Brothers–a huge retailer of ceramics in Brooklyn and other cities–who imported this piece. Here’s their label on the back:

♦ ♦ ♦

This past Friday, Eve M. Kahn devoted her entire “Antiques” column in The New York Times to glassmaker Christian Dorflinger (1828-1915) and the soon-to-open museum of his work, some of it manufactured in Brooklyn and some, later, in White Mills, Pennsylvania. Dorflinger was one of America’s greatest glass manufacturers of the 19th century.

Two of those buildings in White Mills have now been restored. They will open on July 2 as the Dorflinger Factory Museum. Here is Christian Dorflinger’s grave at Green-Wood:

You will find the entire article here.