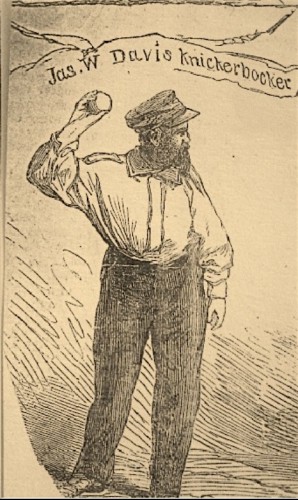

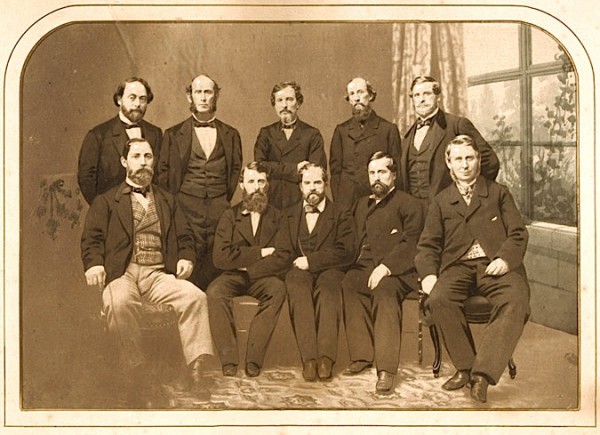

James Whyte Davis was a baseball pioneer. He began playing with the Knickerbockers Base Ball Club of New York City in 1845. He was a leading Knickerbocker player and then an officer of of the club, serving as the Knickerbockers’ president from 1858 to 1860. He wound up with the Knicks tattered early banner–it spent many years draped across his dresser.

In 1893, as James Whyte Davis contemplated his death, he came up with a plan: players and management of the National Baseball League would contribute 10 cents each to honor him with a gravestone. He would save them much work by writing his own epitaph. But, by 1893, James was long-forgotten, and the plan went nowhere. He died in 1899 and was interred, as he had planned, wearing his Knickerbockers uniform and wrapped in the old and tattered Knickerbocker flag. But he got no gravestone.

Fast forward to about 10 years ago. Peter Nash, a baseball researcher, wrote “Baseball Legends at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.” In it, he told the story of James Whyte Davis–and revealed that not only had Davis not gotten the gravestone he had asked for, with the epitaph he had written, but he had no gravestone at all.

The Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) recently created its 19th Century Baseball Grave Marker Project. Its first task: marking James Whyte Davis’s grave.

So, this past Saturday, on a lovely spring morning, a crowd gathered at James Whyte Davis’s grave. John Thorn, major league baseball’s official historian, and Peter Nash, spoke about Davis. Two great granddaughters of Doc Adams, a member of the Knickerbockers who had played with Davis on the Knickerbockers and had written out the early rules of baseball–a document that sold just days earlier for $3.26 million, read a letter that Adams wrote.

Ralph Carhart, who led the gravestone effort, spoke about Davis and the efforts to finally get him his gravestone.

“Ball Days,” the first baseball song, written by none other than James Whyte Davis, was sung. The lyrics mentioned many of the men who Davis had played with and against–and who are interred at Green-Wood: Doctor Joseph Jones, Gus Dayton, John Holder, Thomas Dakin, Thomas Van Cott, Louis Wadsworth, Thomas Miller, and Charles DeBost. Then the polished granite gravestone, with the epitaph that Davis wrote more than a century ago, was unveiled. Note the logos of SABR and Major League Baseball–both of which contributed the money necessary to get this gravestone made and installed.

After the unveiling of the gravestone, Tom Gilbert, author of “Playing First: Early Baseball Lives at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery,” led a baseball trolley tour across Green-Wood’s grounds, stopping at the graves of many of James Whyte Davis’s Knickerbocker teammates and several others who pioneered the National Pastime: the game of baseball.

One particularly poignant stop was at the grave of Louis Fenn Wadsworth. John Thorn spoke eloquently there of his search for a man who had been named in the Mills Report of 1907, an investigation into the origins of baseball, by the name of “Mr. Wadsworth,” who had played a key role in baseball history. But the report gave no first name and John had spent years trying to track this Wadsworth down. Just weeks ago, he posted his findings here. It is a fascinating read! Here’s just a small part of this remarkable story: when baseball’s pioneers met in convention in 1857, one of the matters to be determined was the length of games. The practice had been to play until one team scored 21 runs. However, the players wanted a different rule; they agreed, in a vote, that a game would last 7 innings. The newspapers reported this decision. But, after those reports had gone out, Louis Fenn Wadsworth stood before the convention and made an impassioned plea that a game last 9 innings; he was so convincing that the convention reversed itself and agreed to his proposal. Wadsworth went on to become a judge in New Jersey, then sadly became an alcoholic, drank away his fortune, and signed himself into a home for indigents in Plainfield. There he lived the last 10 years of his life in complete anonymity, never having a visitor, but always, for reasons unknown to the others there, interested in the scores of baseball games.

Another highlight of the tour was a stop at the lot of Henry Chadwick, who was dubbed “Father of Base Ball” by none other than President Theodore Roosevelt. Chadwick invented the baseball scoring system–6-4-3, for instance, for a ground ball to the shortstop that was thrown to the second baseman and then on to the first baseman for a double play. Chadwick also coined many classic baseball terms: assist, base hit, base on balls, cut off, chin music, fungo, white wash, double play, error, goose egg, left on base, and single.

Chadwick’s monument, paid for by A.G. Spalding and Charles Ebbets, is spectacular, with his name, life dates, and “Father of Base Ball” inscribed on a bronze baseball diamond on its front, and crossed baseball bats, a catcher’s mask and a glove on the sides. It is topped by a large granite globe, a Victorian symbol of eternity (with no beginning and no end). But this globe is very special: laces–looking just like those on a baseball–have been carved into it. That’s all great–but this trip to the Chadwick grave was even more exciting than usual. The lot, more 108 years ago, had its corners marked by granite carved to look like baseball bases. Just days before this visit, Green-Wood staff installed basepaths to connect those bases. It looked great!

One final note. Years ago, John Thorn came up with a new way to note your visit to the grave of a baseball man. Not by leaving a coin or a small rock. Rather, by leaving a baseball. And, that ritual has caught on–note all of the baseballs that have been left by visitors at Henry Chadwick’s grave.