Almost four years ago, Green-Wood purchased the New York City landmark Weir Greenhouse. Work to convert it into a visitors center is proceeding apace; hopefully it will be open by the end of 2016. Soon after the purchase of the Weir Greenhouse, Green-Wood purchased the adjoining real estate of the Brooklyn Monument Company. The two buildings on that property are being torn down to create space for a new building with an exhibition gallery, library, conference room, archival storage and offices.

The owner of the Brooklyn Monument Company left many of its business records when he retired and closed up shop. We felt that these records created a great opportunity to tell an important story related to Green-Wood’s–that of a monument-making business closely related to the cemetery. So, our archivist, Tony Cucchiara, our manager of collections, Stacy Locke, volunteer Jim Lambert, and I spent hours in very dusty conditions gathering materials to be saved. There were file cabinets from the 1950s and 1960s full of orders for monuments–with sketches. There were monument catalogues. But we didn’t find anything really early.

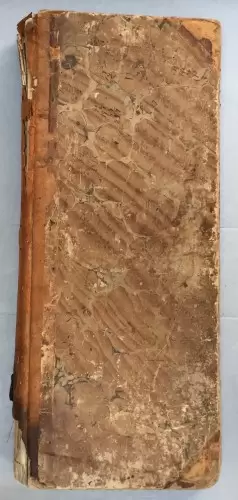

However, it turns out that there was one early record book there that was a real gem. It was found as the tear down process proceeded. It did have a promising look to it:

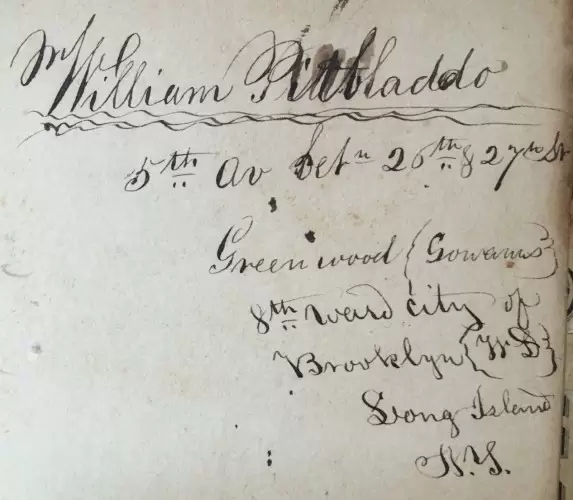

But what was this book? This inscription, at its beginning, began to reveal its story:

William Pitbladdo/ 5th Av(enue) bet(ween) 26th and 27th St./ Greenwood (Gowanus)/ 8th Ward City of/ Brooklyn (W[estern] D[istrict])/ Long Island/ N.Y.

So who was William Pitbladdo? He was born in Scotland in 1806, immigrated to America from Ireland in 1836 and started his monument-making business near Green-Wood in 1842. He became a United States citizen in 1851. His son Thomas, born in 1832, later took over the business from William. Then it was Thomas’s son, Grant, who wound up running it, followed by his sons, William and Kenneth.

The business moved a bit over time. So, according to the entry above, William’s business, in 1856, was on Fifth Avenue between 26th and 27th Streets. That makes sense–in 1856, the funeral entrance to Green-Wood was where William Pitbladdo’s business was located–at 5th and 26th-27th. According to the Worldwide Masonic Directory of 1860, William Pitbladdo was in the granite, marble and freestone business at the corner of 27th Street and Fifth Avenue. And, when Green-Wood moved its entrance to the east side of the intersection of 25th Street and Fifth Avenue (where it still is today), William Pitbladdo moved two blocks north on Fifth Avenue, to the southwest corner of that same intersection. According to the 1865 New York State census, Pitbladdo was 58 years old, living with his wife Cherry in a brick house valued at $8000, and was a “Stone Cutter.” In fact, according to his will of 1869, he owned the property from the southwest corner of 25th Street and Fifth Avenue down 25th Street for a distance of 150 feet. That is the land under what is now the Weir Greenhouse as well as the land where the Brooklyn Monument Company’s buildings now stand.

I bought the below photograph–a stereoscopic view of Green-Wood’s 25th Street and Fifth Avenue entrance–about 20 years ago. I was intrigued by this early view–circa 1865–of Green-Wood’s entrance road and the intersection of 25th Street and Fifth Avenue. It also seemed to have some interesting details in the distance–though I was unable to make them out when I bought it. Here’s a close-up of the businesses on the west side of Fifth Avenue:

William Pitbladdo died in 1870 and, fittingly, was interred at Green-Wood. His wife, Cherry Humble Pitbladdo, as well as their son Thomas, and other members of the Pitbladdo family, are interred in section 58, lot 3221.

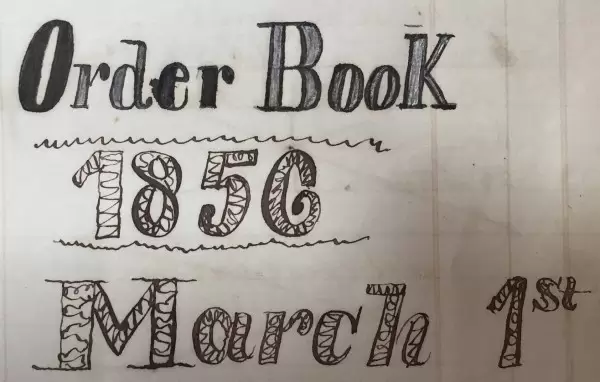

Since the discovery of William Pitbladdo’s Order Book, I have been able to look through every page of it. It tells a fascinating story! Here’s its first page:

The order book runs almost 120 pages and offers a fascinating insight into the monument business serving Green-Wood between 1856 and 1867. It records just under 1000 orders–ranging in price from pennies to thousands of dollars. A few of the entries specify that the monument is to be installed in Green-Wood. But none specify any other cemetery–and the vast majority of those I was able to identify by client name and job description did match up with work done at Green-Wood. One monument, strangely enough, was ordered for shipment to Tallahassee, Florida.

With respect to work other than the fabrication of monuments or tombs, Pitbladdo offered at variety of services. Non-skilled labor, such as the cleaning of monuments and fence posts, in one case took 12 days and cost $20.62 (the equivalent of $559–quite a bargain by today’s standards for two and one-half weeks of work). Pitbladdo would paint an iron fence–the only color ever specified was “dark green” (I would have have guessed black) for a few dollars. Iron fencing could be ordered “galvinised.” Even “Blue stone coping” was available, as were granite posts as well as iron rail fences and gates. Pointing the Charles Morgan vault–a job requiring more skill than cleaning or painting–took 6 days of labor; the cost was $25.25 ($684 today–still a bargain for labor by today’s standards, at a $114 a day). Letters carved on monuments were 5 cents each (the equivalent of $1.36 today). 195 feet of coping for Jasper Grovesnor was $780 ($21,144 today):

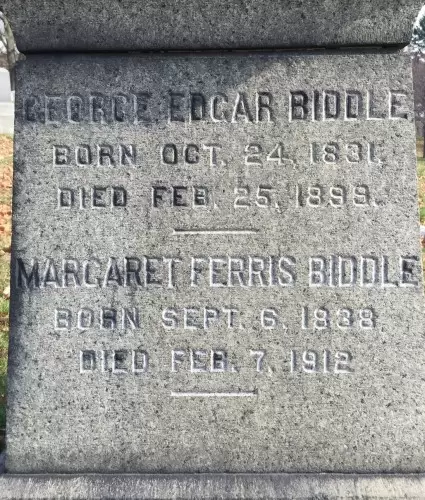

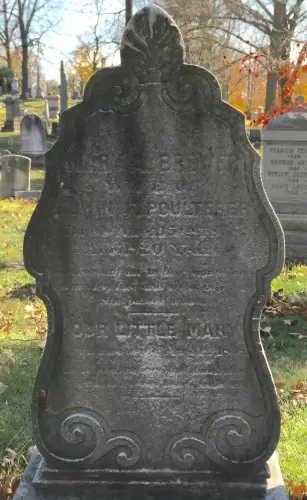

There were other services offered. Blacking–the placing of a black coloring into letters cut into a monument to make them more visible–was a service that Pitbladdo offered. In April of 1867, George E. Biddle contracted for painting of his lot, cleaning of his monument, and “Blacking Letters on Headstone.” The total charge for this was $23.50. And here is that headstone, showing traces of blacking that was also applied years later, after his death and the death of his wife.

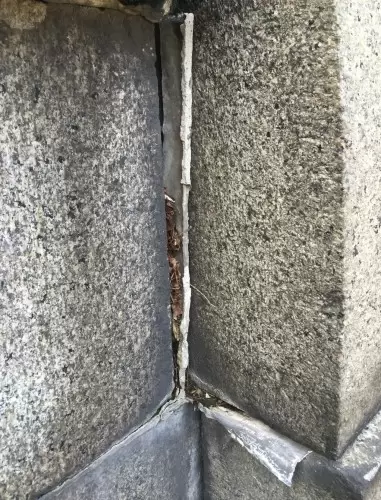

Repairs to leading–the lead strips that were placed in the joints between the stones that made up a tomb–were also done regularly. Here is a photograph of leading that has come loose over the years:

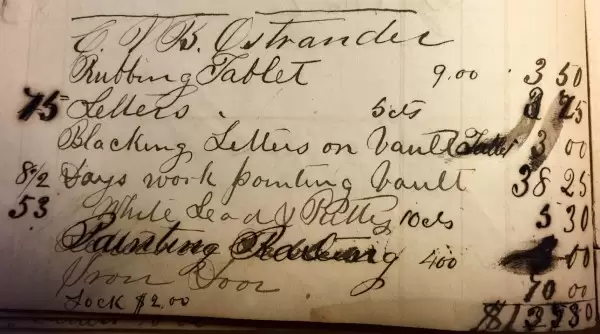

In 1867, C.V.B. Ostrander asked Pitbladdo to do work on his existing brownstone mausoleum. Here it is at Green-Wood today:

Ostrander wanted a tablet rubbed, letters cut and blacked, the joints pointed, white lead and putty repairs made, and painting done. He also ordered a lock for $2 ($31 today) and an iron door for $7 ($109 today). This is the entry in the Order Book for this transaction:

Here is the iron door Pitbladdo supplied:

Terminology is interesting: only a rare reference in the Order Book is made to a tomb and none to a mausoleum; rather, the terms used by Pitbladdo for above ground buildings are catacombs and vaults.

A note on Green-Wood’s early lot sales and burials. Green-Wood Cemetery was chartered by the State of New York on April 18, 1838. The next two years were spent in selling lots and fixing the place up: combing rocks off the hills, raking tons of manure into the ground, laying out paths and roads, and contouring hillsides. The first burials at Green-Wood occurred on September 5, 1840–and those burials were in lot 233. Earlier lot numbers appear to have been reserved for large purchasers–Henry E. Pierrepont, Green-Wood’s founder, purchased lot #1 on August 15, 1842–after several hundred lots had already been sold and assigned lot numbers in the low hundreds. Two years later, by the end of 1842, there had been a grand total of 89 interments at Green-Wood. By January, 1850, 3671 lots had been sold. By March, 1858, business had picked up: by the time this Pitbladdo Order Book was put into use, 11080 lots had been sold. As of December 2015, 45,704 Green-Wood lots have been sold.

The cemetery appears to have been treated as something of an open air showroom. Orders were placed for monuments or iron gates by name of those already on the grounds: a monument “like Stevenson,” gates “like Bleakley.”

Using Green-Wood’s records and the information in the Order Book, we were able, in many cases, to determine the lot to which the order pertained. Unusual names paired with low (and therefore early) lot numbers helped with making these matches.

During the period of the Order Book–between 1856 and 1867–three types of stones for monuments were available from Pitbladdo: brownstone, “Italian Marble,” and granite. Brownstone was out of fashion by this time. But John B. James ordered a “Brownstone Headstone” on July 22, 1865. It was for “Little Fannie,” who had died that very day:

All of Pitbladdo’s marble orders are for “Italian Marble.” This likely means marble imported from Italy, rather than just a reference to a commercial grade of stone. We were able to track several examples of Italian Marble monuments by Pitbladdo at Green-Wood. They are, by and large, simple and rather uninspired. Nevertheless, it is interesting to see the age of these monuments and their comparative prices. Here are examples of his work:

Granite monuments were also available. Granite is a very dense and hard rock. It survives in the elements very well. Take a look at these monuments–they show little if any wear after more than a century and a half outdoors:

Large granite obelisks seem to have been quite popular in this period. Here is a comparison of several:

A granite vault, with granite coping and a railing around it, and with “Hallett to be cut on front of vault,” was ordered by T.S. Hallett on September 8, 1860. The cost was $3950–equivalent to $109,400 today. This is it:

Pitbladdo worked on some of Green-Wood’s most interesting and elaborate mid-19th century tombs. This is the Jerome Mausoleum:

Leonard Jerome, a notorious stock manipulator, and his wife, Clara, had a daughter named Jennie; she was born in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, married Sir Randolph Churchill, and gave birth to Winston Churchill.

Pitbladdo took the order for John Anderson’s Greek Revival “underground vault” in 1863; it cost $16,000. Anderson made his fortune in tobacco and that is a whole lot of tobacco! It translates to $295,000 today:

On June 3, 1864, Peter Moller ordered this tomb at the agreed-upon price of $19,000–the equivalent of $278,246 today:

On June 27, 1860, Isaac N. Phelps agreed to pay $11,000 ($304,670 in today’s dollars) for the construction of “1 Marble Vault to be built as per Plan.” In today’s money, this is the most expensive tomb Pitbladdo billed in this Order Book:

Crockets–stylized carvings of buds, flowers, or leaves used to decorate spires, finials, and pinnacles of Gothic Revival architecture–were billed to Isaac N. Phelps at an additional $500:

As we printed section maps of Green-Wood so that we could find Pitbladdo’s work on the grounds, a surprising pattern emerged: many of these monuments were right along Green-Wood’s avenues. Undoubtedly, prime locations in the cemetery were those along the roads. They had the easiest access, were the simplest to find, and were the most visible. Further, highly-visible monuments would add to the excitement of tourists who came to take “The Tour”–a prescribed route through Green-Wood featuring such attractions as “The Mad Poet” and “The Indian Princess”–which had the ultimate goal of increasing lot sales. One wonders if Green-Wood’s sales force of the mid-19th century–when the cemetery had only been selling lots for two decades– encouraged lot buyers to purchase lots along the roads, rather than farther back, so that the cemetery would look that much fuller, thereby impressing visitors while also encouraging prospective customers to buy so as not to lose out.

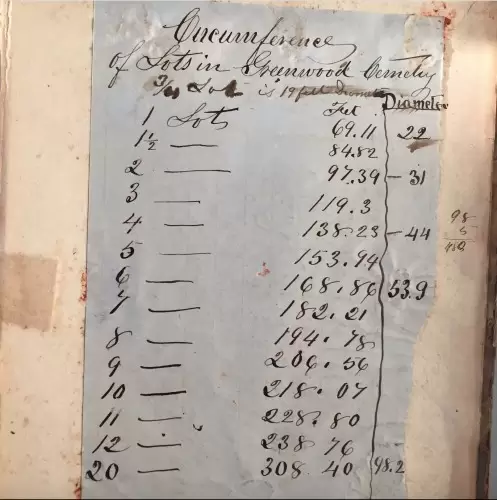

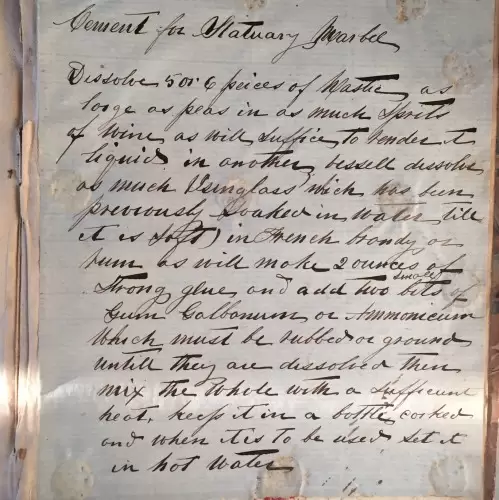

Inside the back cover of the Order Book appear two interesting documents:

In the 1870 Brooklyn Directory, William Pitbladdo is listed in the marble business at the corner of 5th Avenue and 25th Street and living on 25th Street. He died in February, 1870, leaving an estate described in his will as “less than thirty thousand dollars.” He was interred at Green-Wood on the 13th of that month–at the end of a long and successful Green-Wood career. Today the memorials that he created more than a century and a half ago stand as monuments to him. And his Order Book that he kept from 1856 through 1867 provides insight to the cemetery’s development and to monument making in America–detailing the monuments and tombs that were being fabricated during this period and their prices. It is a great find!

Hi, i stumbled across this site, and find it very fascinating. My great great grandfather was a stonecutter in Brooklyn, and he actually worked for Thomas Plitbladdo. I was hoping there might be some information about him in the book you found. His name was Thomas F. Molen, and he died in 1917 in Brooklyn. This except is from his obituary, published in the Brooklyn Eagle: Mr. Molen was one of the oldest members of St. John’s Church. He was born in Cahir, County Tipperary, Ireland, and came to this country in 1851, settling in South Brooklyn, where he had lived ever since. Mr. Molen was a skillful granite monument cutter, and was for years in the employ of Quinn Bros., Thomas Pitbladdo and John Wade, monument dealers of the vicinity of Greenwood Cemetery.” Thank you for your time!

Thanks for sharing your great great grandfather’s story. William Pitbladdo’s account book, about which I have written, covers his work from 1856 to 1867–which may have been before Thomas F. Molen was working as a stonecutter. In any event, the Pitbladdo account book makes no mention of the men working for him as stonecutters–the only names mentioned in it are those of his customers.

Thank you so much for your reply. I suppose my gg grandfather Thomas worked for William Pitbladdo’s son Thomas during the 1870-1890 period. The book sounds like an incredible discovery.

This is a wonderful story. William was my great-great-great grandfather! Thank you for sharing.

He was also my great-great-great grandfather. I thoroughly enjoyed the story. Kenneth Pitbladdo who was mentioned early on in the story was my grandfather and I have many great memories of that fine and hard working man.

Thanks, Larry. Glad you enjoyed it! It is quite a story–and his carefully-kept account book made it possible for us to tell it.

are you related to a John Pitbbladdo?? he was once a foreman for the Truro Co. in or around the 1850s

sorry, i meant Pitbladdo

Amazing and so fortunate to find this early, prime source.

Why this particular ledger was saved for so long while others were discarded can only be speculated upon.

Always wondered what the original costs were and this story answered so many questions. This was a great informative article. Thank you for sharing it.

Glad you liked it!

Thank you! Fascinating research. Only quibble I have is near the top:

“So who was William Pitbladdo? He was born in Scotland in 1806, immigrated to America from Ireland in 1836 and started his monument-making business near Green-Wood in 1842. He became a United States citizen in 1851. His son Thomas, born in 1832, later took over the business from William. Then it was Thomas’s son, Grant, who wound up running it, followed by his sons, William and Kenneth.”

Grant’s son William, mentioned in the last line above, was my father. I believe it was Grant’s oldest son Willard who followed in the business. My dad William didn’t.

Thank you very much, Janet, for the correction. My mistake.

My Great Great Grandfather, Peter Scott Kay, a War of the Rebellion Veteran that enlisted 3 times ( 51st New York Volunteers), was a stone carver at Greenwood Cemetary. He is buried in lot 26505 section 200 1903 July,12

Thanks for sharing! He is one of the approximately 5,200 Civil War veterans who we have identified as interred at Green-Wood, and for whom we have researched and written biographies. You will find his here: https://www.green-wood.com/2015/civil-war-biographies-joiner-kimball/