I am always on the lookout for items pertaining to Green-Wood and/or its permanent residents. I look for such items online, at auction, in catalogues, and at shows.

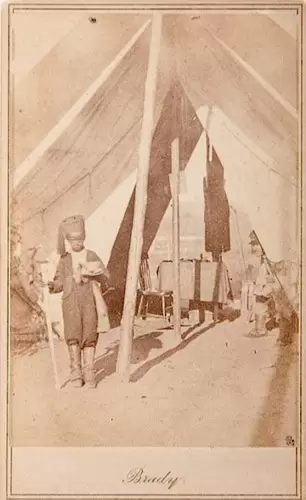

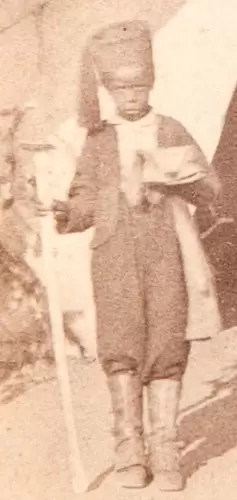

I came across this carte de visite photograph, taken during the Civil War, listed in a recent Cowan’s auction:

And here’s the catalogue description:

CDV of an outdoor camp scene, featuring a young African American servant wearing a fez-type hat with long tassel, shell jacket, and boots, and holding an officer’s sword in his right hand, and a sash and tray with cup and saucer in his left hand. The officer, identified in pencil on verso as Lt. Col. Lloyd Aspinwall, 22nd NYSNG, at Harper’s Ferry, VA, 1862, is visible at right, peeking out from inside the tent. With Mathew Brady’s New York and Washington, DC, studio imprint.

What first attracted my attention was the identification of the soldier, peering out from the right, under the tent flap, as Lieutenant Colonel Lloyd Aspinwall. I recognized him–and his name– as one of the almost 5,000 Civil War veterans that Green-Wood’s Civil War Project has identified as being interred there. His biography, posted just weeks ago, appears on Green-Wood’s website, along with those of 5,000 others who played a role in the Civil War. Just click on this link and search for Aspinwall.

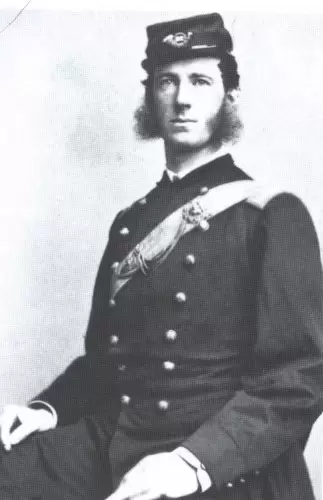

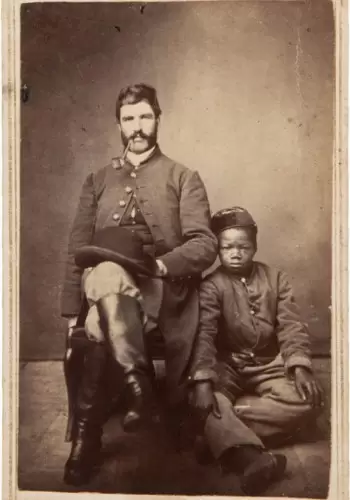

Here’s a very nice portrait of Lloyd Aspinwall, taken during the Civil War:

And here’s another image of Aspinwall:

Here’s the detail of the photograph that was listed in the auction catalogue, showing the Union officer:

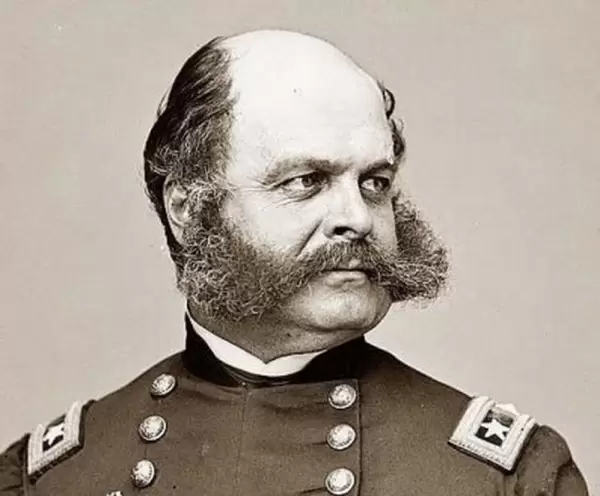

Is this Lloyd Aspinwall, peeking out from inside the tent? Likely so, I think. Both of the above photographs, known to be of Lloyd Aspinwall, show him with his characteristic sideburns (a term that traces its origins to the Civil War, and grew out of (so to speak) the facial hair of General Ambrose Burnside–full mutton chop whiskers and a mustache, but no chin whiskers and therefore not a beard). Here, for your delight, a portrait of the good (actually, not so good when it came to commanding an army) general:

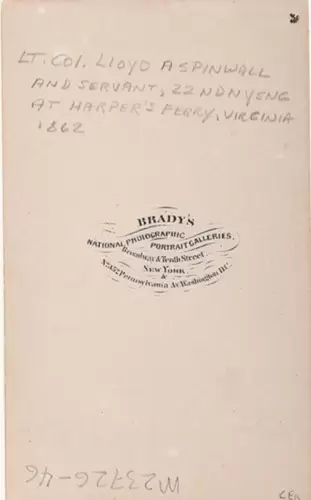

Further, the back of the carte de visite contains a note identifying the officer pictured is Lloyd Aspinwall:

While this notation does not seem, to my eye, to be from the 19th-century, it is helpful in confirming the identification of Aspinwall. Clearly someone who owned this–likely an expert collector–thought it was Aspinwall.

When was this photograph taken? The notation on the back of this photograph–that it was taken at Harper’s Ferry in 1862–it helpful. The 22nd New York State Regiment was activated in 1862 from May 28 to September 6. Lloyd Aspinwall, 28 years old, was its lieutenant colonel during this service. The 22nd was at Harper’s Ferry and stationed near Baltimore during this period–but saw no combat in 1862. It was in camp–and this photograph is a camp photo. So it appears to date from 1862.

Now let’s take a close look at the carte de visite that was for sale (and which Green-Wood was able to buy). It has two unusual aspects. First of all is the young African-American at left, in the foreground:

He is a young boy, likely a slave just months or even weeks before this photograph was taken. He holds an officer’s sword in his right hand and what looks like a cup and saucer in his left hand. War and domesticity. Two aspects of the early Civil War. Fighting battles, then setting up camp for the long weeks and months between battles.

By no means is this photograph of a Civil War soldier and his African-American servant unique. These relationships were a matter of benefit to both parties–Union officers (and sometimes even Union privates) as well as black boys. Early in the war, most of the soldiers’ time was spent camping. Battles were few and far between. The men used their free time to make their service as comfortable as possible. A cook or a servant, hired at minimum cost, would greatly help this effort. And black boys, who had fled slavery for Union lines, often had been separated from any source of support–and often were desperate for a place to live. Working as servants for Union troops offered them an opportunity for food and perhaps some modest payment. And some protection from being captured by their former owners and returned to bondage.

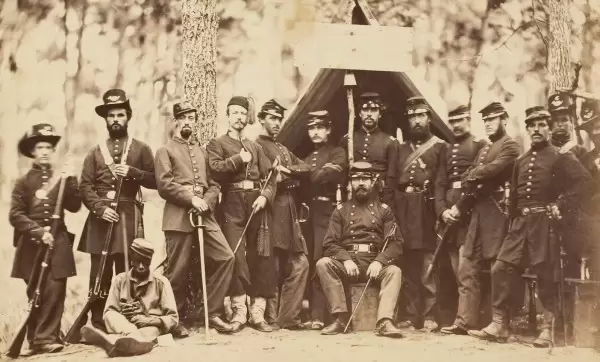

Here are a few similar images, showing white Union troops and black servant boys:

Note that in the above image the black servant boy is separate from these Union men; he sits on the ground, alone, below them, and is the only person in the photograph (except for one officer, third from left) not wearing Union blue. You will find more such images of “African American Servant Boys” of the Civil War in this post on the website “Civil War Talk.”

What is particularly intriguing about the photograph of Aspinwall and his servant boy is the relative positions of the two figures. The boy is the featured individual in the image; he stands in the foreground, holding props. In contrast, the white officer is in the background; he is secondary. And, unlike the typical Civil War photograph, which features the individuals looking directly and squarely at the camera, Aspinwall peeks out at the camera but is not firmly engaged with it. He sits, the boy stands. Aspinwall, unusually, is the subsidiary character in the image–a white officer subservient to a black servant, deferring to him.

One final note. This carte de visite is identified both on its front and its back as a Brady photograph. This means, of course, that it was taken and published by the photographic studio of Mathew Brady, the most famous producer of Civil War photographs.

We are happy that we were able to purchase this carte de visite for our Historic Fund Collections. It illuminates an unusual aspect of the Civil War–and pictures one of Green-Wood’s Civil War soldiers.

Enjoy the photographs. Did these children qualify for pensions, etc. after the war?

No, I do not believe that they did. Pensions were available to those who formally served the United States government. And even soldiers and sailors were not eligible for pensions–unless they had been disabled–until decades after the Civil War ended. This young fellow would have been hired by Lloyd Aspinwall–for a fee, for food, for a place to stay?–by mutual agreement–and would not have qualified for a U.S. pension. Did he have a family working nearby? Was he on his own? We don’t know.