By the 1850s, Green-Wood was second only to Niagara Falls as an American tourist attraction. Many guides were written over the years describing Green-Wood’s grounds. Those guides offer great and varied information. Always on the lookout to increase my Green-Wood knowledge, I recently came across a guide to Green-Wood from 1901, written by Louisa Richardson: “Greenwood As It Is,” on the website of the Library of Congress:

The guide has some very interesting information in it–which I have investigated on your behalf, dear reader. The results of those investigations are below.

It appears that spelling was not Louisa’s long suit. So, in the title to her guide, she spells Green-Wood as Greenwood. This, of course, is a common mistake. So it is one that is easy to forgive. However, some of her spelling errors in the book are quite extraordinary. For instance:

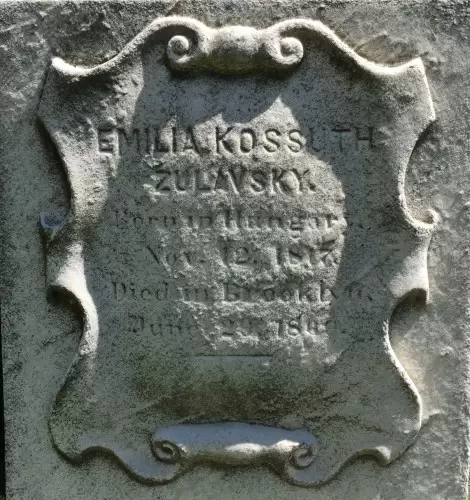

Very few persons visiting Greenwood are aware that in these grounds lies the body of Amelia Korsouth, wife of Louis Korsouth, the Hungarian patriot who was banished from his country on account of his patriotism. His wife, who shared the same feelings, came with him. She always expressed the wish that her body should lie in this country until her country was free, at which time she wanted her remains removed to her native home.

This is, of course, a very interesting little story. But Ms. Richardson is very much off the mark with her spelling. The last name of the famous Hungarian patriot is Kossuth, nor Korsouth.

Further, Emilia Kossuth was not the wife of Louis Kossuth, as Ms. Richardson reports; she was his sister. Here is the inscription on the front of her Green-Wood monument:

The author goes on to record the inscription on one side of the monument at Green-Wood for Emilia Kossuth, who died in 1860, her hope that someday, when Hungary would be free, her remains would be interred in its soil: “Ye who returns when Hungaria is free, takes my dust along, my heart is there.” That inscription is still visible; it is Hungary, not Hungaria, as Ms. Richardson spelled it. It appears, however, that no one ever followed up on Emilia Kossuth Zulavsky’s wishes; her remains are still buried at Green-Wood.

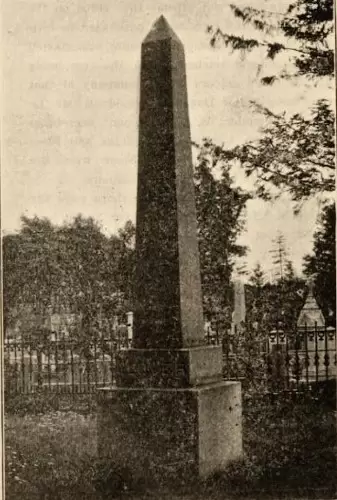

On page 21 of her guide, Ms. Richardson notes that the first obelisk was erected at Green-Wood in 1839 where the monument to J.B. Graham now stands. I have read about that obelisk before–that it was near Green-Wood’s main gates, where Sycamore, Willow, and Landscape Avenues meet, not far from where the Historic Chapel now stands. It was placed there by the cemetery’s management to dress the grounds up a bit in their early years, before any burials had occurred. According to Louisa Richardson’s account, “It was removed later and now stands in the lot of Steven B. Munn . . . .” That is very interesting! So Jim Lambert, volunteer extraordinaire, checked Green-Wood’s burial records for me and, lo and behold, there is a Steven B. Munn who was interred in lot 1312, at the corner of Alder and Central Avenues, in 1855. Out we went to that lot. There are several monuments there to Munn family members, and on the ground at the side of an adjoining lot lay this gravestone:

Below is the image in the guide on the page opposite the description of the obelisk; though the guide does not specify that the obelisk pictured is the one that was in the Munn Lot, I think that it is reasonable to assume that that is the case. So this is what we were looking for:

Looking around the lot, there was no obelisk–an obelisk is not something you would miss. But I did find this–which may be part of that 1839 obelisk:

We will investigate further.

Update (as of September 4): The investigation has been completed and the mystery of the missing obelisk is solved! Cara Lowery e-mailed soon after the blog was posted to note that she saw a name on the front of the obelisk across the middle stone that she read as “CLOVER.” I had not noticed that; I checked a magnified version of the image above and that seemed correct. However, when I went out to the Munn Lots (it is actually 6 lots in all) today, I noticed that one of the branches of the family is GLOVER. That was intriguing. Might the family name carved on the old obelisk have been GLOVER, not CLOVER? Or was this just a coincidence?

As we examined the Munn lots today, we noticed this at the edge of the lots:

This was a curious piece. It seemed to be more 20th century than 1839, particularly because of the way it was cut; though it is difficult to see in this photo, both the top edge and the base extending into the ground are rounded. Further, typically in the 19th century planters at Green-Wood were of cast iron, not stone.

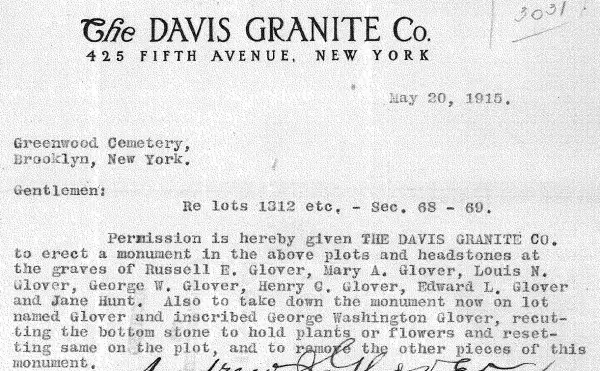

After examining the lot with Frank Morelli, Green-Wood’s supervisor of restoration, who pointed out that the gray stone flush with the ground (pictured above) was in fact the entrance to an underground vault and not a part of the obelisk, he offered to examine the lot further. However, before he did that, we went to check the burial orders for those lots in Green-Wood’s offices. The cemetery’s archives of burial orders are a rich source of information pertaining to monuments. And look what we found:

This note explained the planter with GLOVER across its front–it was the recut middle piece of the 1839 obelisk–upon which GLOVER appears on the photograph from the 1901 guide!

But what had become of the two other pieces of the three-piece obelisk? Another note in the file concerning foundations that were to be built in the lot to support new monuments, dated October 30, 1915, from the Davis Granite Company to Green-Wood, specifies that “The two old pieces of the monument taken down are to be put in the foundations as near the top as possible.” So all three pieces of that 1839 obelisk are still in the Munn Lot; one has been recut for use as a planter and two have been buried in the lot for use in the foundations. Mystery solved!

Returning to our tour guide author, Ms. Richardson, she notes on page 75 of her work:

At the corner of Zephya Path and Cypress Avenue is a plot with seven graves in it and is as yet unmarked, although it is expected that the Colonial Dames will soon mark the spot. It would have been done before only on account of a dispute as to the right of the marking of the same. In it lies the remains of Captain Reid, who is claimed to have been the designer of the first American flag. His mound is the center one in the rear row.

A few things here. It is Zephyr Path–not Zephya Path. This lot has an interesting history. No monument was there until 1956; here’s the story of the monument that now stands there, from an earlier blog post. And here’s another blog post about two Confederates, Major Reid Sanders and his father George, who are interred in that same lot.

Checking the cemetery’s records, the Reid lot was purchased by William J. Reid and Aaron B. Reid in 1861 for $170. It is 378 square feet. It is unclear why no monument was placed there for almost a century–the Colonnial Dames did not get the job done. However, in 1956, two descendants of the original purchasers authorized the placement of the monument that now stands there.

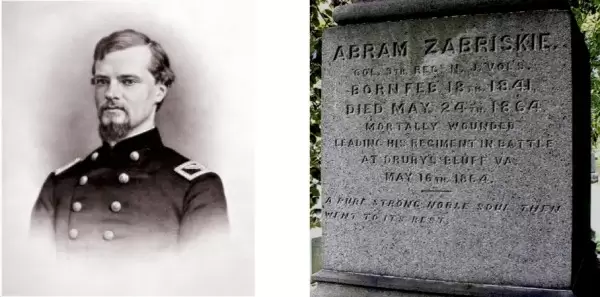

According to Ms. Richardson’s guide, Benjamin Franklin Tracy placed a marble column in his family lot “in memory of his wife and daughter, who were burned to death in Washington, D.C., at the time of the destruction of their home.” I do know a good deal about Benjamin Franklin Tracy. He is one of our Civil War veterans–and a Medal of Honor winner. As a part of our Civil War Project, we have placed a bronze marker in his lot:

Tracy commanded the notorious Elmira Prison Camp, where many Confederates suffered and died. He practiced law and successfully defended Rev. Henry Ward Beecher at trial against Theodore Tilton’s suit for alienation of affection (and adultery)–“The Trial of the Century” in 1875. Tracy and Beecher are interred just feet from each other. Tracy went on to become United States secretary of the navy.

So I was off to the Tracy lot. Not to quibble, but the difference between marble and granite is pretty apparent. I have no idea where Ms. Richardson got the idea that Tracy family had a marble column in their lot; here’s the lot’s central marker:

But Richardson’s information about the death of Tracy’s wife and daughter is accurate. Here are their granite gravestones:

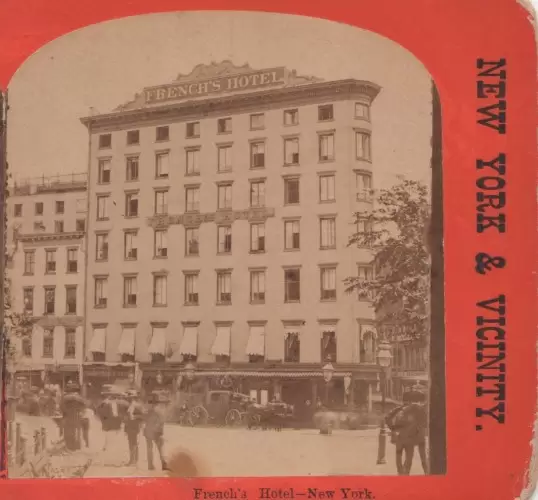

At the corner of Central Avenue and Evergreen Path, Ms. Richardson reports, stands a “massive column elaborately carved, erected by French, who at one time kept the celebrated hotel by that name in New York.” That was a good description of location; standing at the intersection of that path and road, I saw this great monument:

“French’s Hotel” rang a bell–I have owned a photograph of that 19th century accommodation for years. This was the source of income that allowed the French family to pay for this elaborate monument:

French’s Hotel opened in 1849 and was renovated in 1859 by architect John B. Snook (who is also interred at Green-Wood–and who designed the first Grand Central Station). Judging from this elaborate monument, proceeds from the hotel supported the French family quite well.

Marble was the preferred stone for monuments at Green-Wood in its early years. It is a bright white–eye-catching. And it is a soft stone, easily carved and beloved by sculptors. Ms. Richardson tells us, on page 101 of her guide, that “A short distance down on Battle Avenue is the magnificent burial plot of Gabbicoth, who was the first importer of Italian marble to this country.” This was intriguing, as all significant firsts are. But Ms Richardson really outdid herself here: Jim Lambert, out searching with me, spotted the Fabbricotti Family Lot at the described location–and suggested that it was possible that somehow our tour guide writer and morphed Fabbricotti into Gabbicoth. The location was right. There was some very nice marble work in the lot:

I just did an Internet search for Fabbricotti marble and several interesting items came up, including this text from a Time magazine article of 1928:

Since that day, the family has hewed marble. When Columbus set sail in a tiny caravel, a Fabbricotti was grunting, hoisting marble blocks. When Washington shivered at Valley Forge, a Fabbricotti sweated under a hot sun, polishing and smoothing white stone. When a World War became the echo for an assassin’s shot, Fabbricottis heard not. They were quarrying marble.

The Fabbricottis are still in the marble business. This stone that is quarried in Carrara, Italy, and available commercially today:

It is called Calacatta Fabbricotti–a clear indication of that family’s deep involvement in the marble importation business.

This must be the lot!

Nearby, according to Richardson, on Lake Path off Battle Avenue, is the Evans plot, with “a large granite column surmounted by three angels.” This was an easier one. I knew of three angels at this location–I have photographed them several times with fall foliage behind them. So we walked over to them–and they were indeed in the Evans plot:

Here was another easy one to find: “The handsome vault of Dewey, the wine importer of San Francisco, is directly to the rear of the Charlotte Canda monument.” The Charlotte Canda monument is an excellent marker–it is a large and complex landmark at Green-Wood. This is the Dewey Mausoleum behind it:

I have read in several sources that the Schermerhorn family sold almost 100 acres of their farm to Green-Wood, then erected two mausolea on that very same land. Ms. Richardson adds a further detail: that these Schermerhorn mausolea are “upon the site of their old barn.”

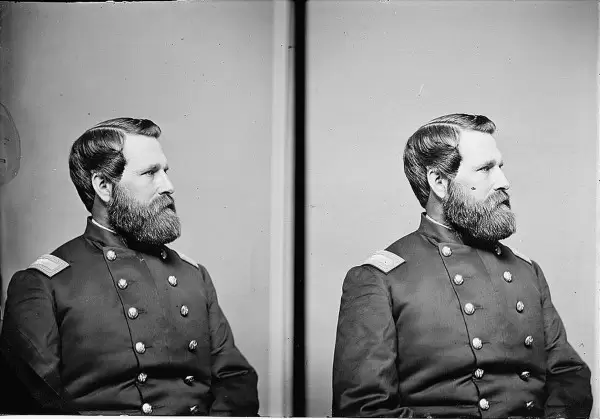

On Chapel Avenue, Ms. Richardson tells us, is “the large and massive, but plain granite column erected over Col. Abram Jabaske, whose lettering tells us, died at the battle of Daway’s Bluff, Virginia, May 16th, 1864.” Now, even by the author’s standards, morphing what I take to be “Drewry’s Bluff” into “Daway’s Bluff” is quite an accomplishment! I searched that area several times for a name like Jabaske with no luck; I will have to do further research on this. I may be able to start in Green-Wood’s chronological books at the date of his death, May 16, 1864, and proceed from there, looking for someone whose place of death is listed as Virginia.

Update (as of September 3): Cara Lowry, Green-Wood aficionado, read the above paragraph and solved the mystery: “Abram Jabaske” is actually Abram Zabriskie. Wow, Cara! The soldier of that name is in fact interred in section 32, lot 14954, which is in the area Ms. Richardson was describing. Here’s Zabriskie and his monument:

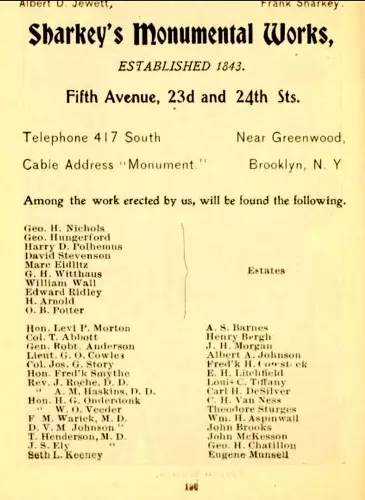

The guide, in addition to its text, offers many full-page advertisements for businesses working at Green-Wood, primarily undertakers and monument makers, as well as photographs taken on the grounds. I found this advertisement to be particularly fascinating:

This advertisement tells us that Sharkey’s was just north of Green-Wood, on Fifth Avenue and apparently running from 23rd to 24th Street. It lists many monuments that Sharkey’s created at Green-Wood, including those for builder Marc Eidlitz, real estate developer O.B. Potter, publisher A.S. Barnes, animal rights pioneer Henry Bergh, E.H. Litchfield (who developed Park Slope), artist Louis C. Tiffany, and China trader William H. Aspinwall. Here is Louis C. Tiffany’s monument:

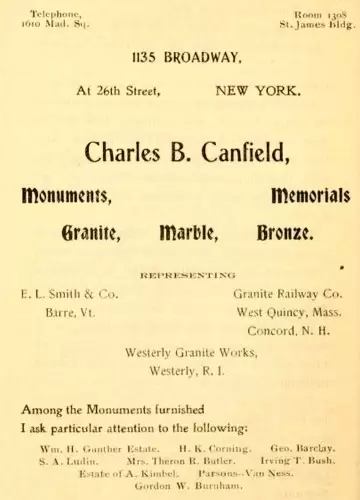

And here’s another advertisement for a monument maker:

Canfield’s work at Green-Wood includes this monument for Gordon W. Burnham, of Westerly granite:

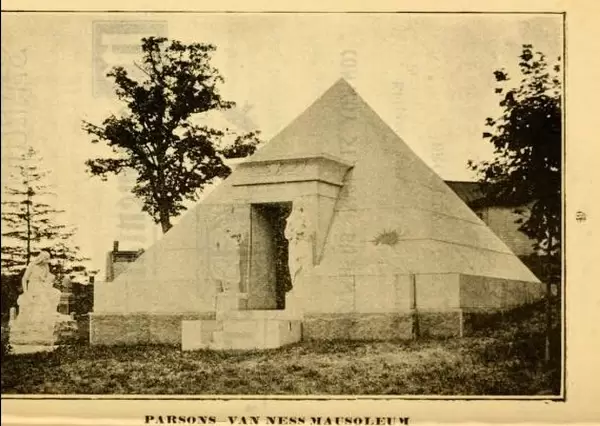

Here’s is the image of Canfield’s Van Ness/Parsons Pyramid which appears in the guide:

What is wonderful here is that this is the first image I have ever seen of the bronze of the Sun God Ra that formerly hung on this tombs’s exterior. Ra appears in the image above on the front right wall of the pyramid. Note that, in the image below, the bronze of Ra, which had been above the sphinx, is missing. I first came to Green-Wood in 1987; that bronze was long gone by then. But the wonderful irony is that the sun itself has burnt the image of the bronze of the Sun God onto the wall of the Pyramid.

I will conclude with one final note concerning Ms. Richardson. She names “Charles Linley Breebe Morse” as the inventor of the telegraph. Not quite; she has really outdone herself here with the challenge she faced of spelling. “Charles Linley Breebe Morse” was, in fact, Samuel Finley Breese Morse. Not very close . . .

In any event, great thanks to Ms. Richardson, somewhat after the fact, for preserving some of Green-Wood’s history. Her guide is a good source of information, preserved for us and those who follow.

Might it not be that the criticism of Ms. Richardson’s spelling is misplaced, and that the fault lies with the printer, who misread what she had written out in longhand?

No, I don’t think so. Based on personal experience, one of the responsibilities of a writer is to proofread text before publishing and sending it out into the world. A few things may slip by, but a large number of gross misspellings of names in a tour guide is not good.