Driving around Green-Wood a few years ago, I noticed a small obelisk along Central Avenue that seemed to have some sort of ship carved into it. It took me a while to get back to that monument to take a closer look, and here’s what I saw:

This is the detail that caught my eye:

But this monument was still a mystery. A mystery which we have now solved.

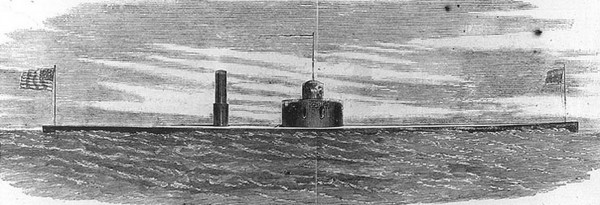

The image above looks like an ironclad Civil War monitor! And, indeed it was.

The monument is inscribed on its front to Third Assistant Engineers Augustus Mitchell , Henry W. Merian, George W. McGowan, and Charles Sponberg.

So how did these four Navy men wind up in the same lot at Green-Wood? What is their story?

Green-Wood’s records, and the inscriptions on the monument, tell us a great deal. According to Green-Wood’s records, lot 2207 was purchased by Mrs. Frances S. Mitchell. A native of England, she was a widow who last lived at 219 East 59th Street in Manhattan and was interred in that same lot on April 25, 1884, at the age of 85. Given this information, she likely was Augustus Mitchell’s mother. The monument, as is carved on its front, was erected by Frances Mitchell and J.J. Merian (likely Henry W. Merian’s father).

This inscription is carved on one of the monument’s sides: “SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF FOUR OFFICERS OF THE U.S. NAVY WHO LOST THEIR LIVES BY BEING DROWNED ON THE U.S. MONITOR WEEHAWKEN TO WHICH THEY WERE ATTACHED WHEN SHE FOUNDERED OFF CHARLESTON, S.C. DECEMBER 6, 1863.”

On the opposite side of this monument appears this inscription: “THE REMAINS WERE EXHUMED FROM THE ENGINE ROOM OF THE WRECKED MONITOR WHERE THEY NOBLY FELL AT THEIR POST OF DUTY. SEPTEMBER 26, 1871.”

These four Navy men had all served on the U.S.S. Weehawken, an iron-clad monitor, which had been commissioned at Jersey City, New Jersey, in mid-January 1863. According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of December 13, 1863, the officers and crew of the Weehawken “were mostly residents of Brooklyn.” Arriving at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 7, 1863, the Weehawken was struck by over 50 enemy cannon balls, but remained afloat.

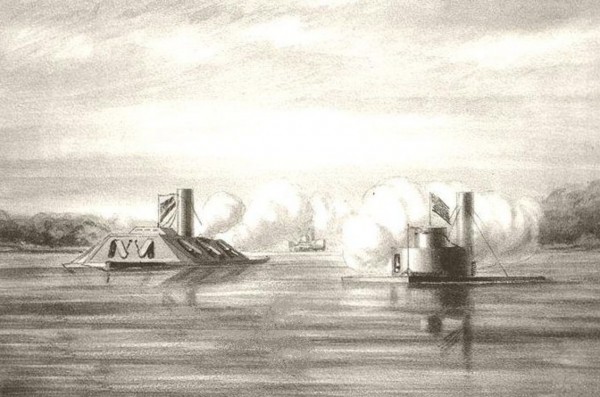

After repairs, the Weehawken steamed off to Wassaw Sound, Georgia, where on June 17, 1863, firing just five shots, she captured the CSS Atlanta, a Confederate ram.

Two of the captured Confederate officers on the Atlanta, Major Reid Sanders (1837-1864) and Second Assistant Engineer Leslie King (1841-1919), were imprisoned at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor; they both would ultimately be interred at Green-Wood.

In August of 1864, Reid Sanders’s mother, Anna J. Sanders (who also is interred at Green-Wood; her father was Samuel Chester Reid, War of 1812 hero who is credited with the idea of changing the number of stars, but not the 13 stripes, on the American flag as new states were admitted to the Union), wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis imploring him to secure her son’s release, but she soon was notified by Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon that that was not possible. Davis subsequently saw to it that Mrs. Sanders received her son’s pay. But Reid Sanders died, still a prisoner at Fort Warren, from dysentery on September 3, 1864. It was not until months later that his mother learned of his death. Assistant Engineer Leslie King survived his captivity and the war to work for twenty-eight years in the Shipbuilding Department of the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a draftsman.

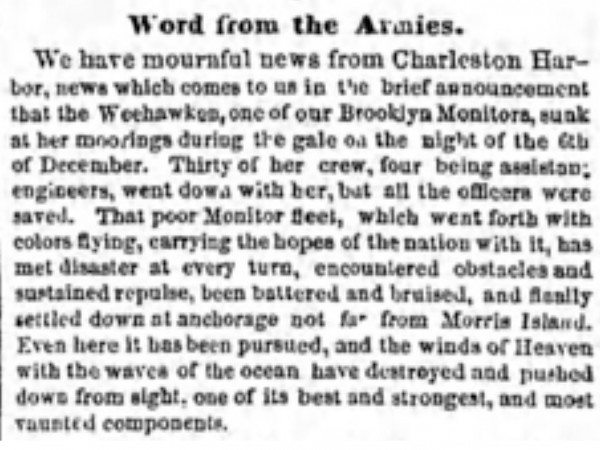

Returning to the harbor at Charleston, South Carolina, the Weehawken assisted in the bombardments of Forts Wagner and Sumter there. After running aground on September 7, the Weehawken again was repaired and became part of the naval blockade of Charleston that October. But, on December 6, the Weehawken suddenly sank in a gale while at anchor off Morris Island. Four engineers and 27 other crewmen, trapped below decks, drowned.

Here is the Brooklyn Eagle’s announcement of the tragedy:

So what had happened to cause the Weehawken to sink? According to one admiral, “the injuries that the vessel had received in service particularly while aground under the fire of the Sullivan’s Island batteries (assisted, perhaps, by the straining produced by being beached at Port Royal) had so strained her that the rivets were loose on some of her bottom plates, and the rough sea that was running at the time of the disaster must have been sufficient to open the plates and admit the water.” Not surprisingly, John Ericcson, who had pioneered ironclad construction, and was responsible for the Weehawken‘s design, was convinced that no such fundamental failure of design had occurred; he attributed the sinking to water entering through the anchor hoister hatch after it had mistakenly been left open by a crew member during a gale. Ultimately, the court of inquiry concluded that a heavy load of ammunition, open hatches, and failures to level the ship once water started to accumulate, resulted in the sinking.

As early as December, 1863, divers were summoned from Port Royal, South Carolina. Upon arrival, they dove and determined that the hull was still in one piece. Pumps and hoses were requested to pump out the Weehawken and then raise it. It was not in deep water; at low water, its pilot house was a foot out of the water. However, it would be almost 8 years later that the Weekhawken, and her crew members who had drowned, would be brought back up.

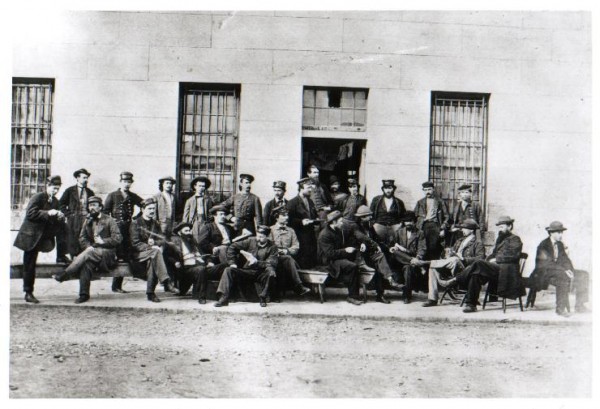

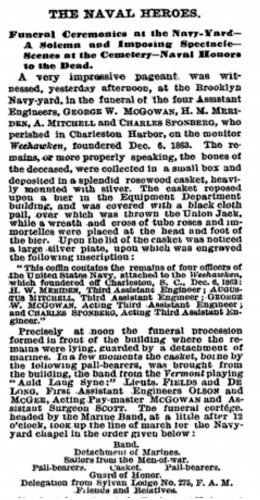

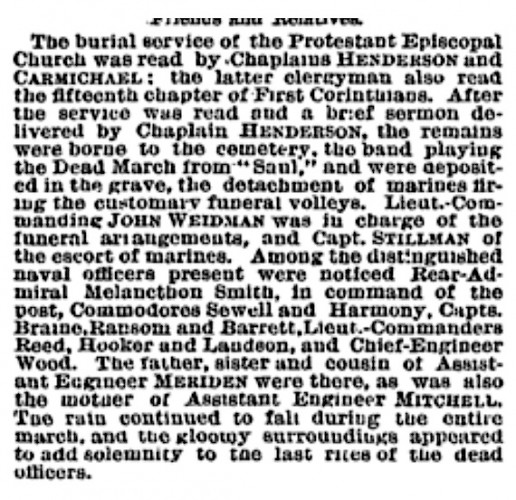

The remains of these men lay in the sunken ship until 1871, when they were recovered. On September 27, 1871, The New York Times reported that the funeral at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for the four assistant engineers was “a solemn and imposing spectacle . . . a very impressive pageant.” The bones of the 4 men had been gathered and placed in a rosewood casket. A silver plate on the casket identified them by name and rank. The Marine Band played. A funeral service was held at the Navy Yard Chapel, then the procession proceeded to Green-Wood, where a band played, Naval officers gathered to pay tribute, and Marines fired volleys in salute.

Here is the full Times account:

Note that Augustus Mitchell’s mother and Henry W. Meriden’s father, sister, and cousin are reported to have been present at the funeral. Mitchell’s mother is likely the Frances Mitchell who purchased the lot at Green-Wood for the burial of her son and his three comrades. And John J. Meriden is likely Henry’s father–who, with Frances Mitchell, erected the monument at Green-Wood.

What of each of the four men interred here? What are their individual stories? Though there is little biographical information available on two of these men–Augustus Mitchell and George W. McGowan (they were likely young men when they died, though we can’t be certain; Green-Wood typically recorded age at time of death for those about to be buried, but it did not do so when remains were being transferred, as here, from another cemetery–they had briefly been buried at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Cemeter), there is a good deal of information available on Henry Walter Merian. A native New Yorker, according to the 1855 census, he was 16 years old and living with his father, a native of Switzerland, in Brooklyn. Henry went on to graduate from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, on July 1, 1858, as a civil engineer. Each year after his graduation, until his death, R.P.I. issued an update on him and his classmates. In 1860, Henry was working as an assistant engineer at the Brooklyn Water Works, and continued working there in 1861. However, he took time off from his civilian career during 1861, early in the Civil War, to serve three months as a corporal with the Engineers Company of the 12th New York State Militia. By 1862 he had moved to New Jersey and was working at a draughtsman at the Trenton Locomotive and Steam Works. He enlisted in the United States Navy on August 25, 1862, and was assigned as an assistant engineer aboard the U.S.S. Weekhawken.

Further, Henry’s father seems to have been John J. (J.J.) Merian, a wealthy resident of Brooklyn Heights. According to IRS records for 1865, the J.J. Merian Company was a wholesale liquor dealer at 76 Beaver Street in Manhattan. An IRS assessment list for 1865 records John J. Merian as living at 22 Pierrepont Street in Brooklyn. His income was $21,969, a very large sum for that time. His gold watch was valued at $100, his pianoforte at $200, and his silver plate at $1495.The 1875 census lists J.J. Merian as 70 years old, a native of Switzerland and a retired commission merchant living at 22 Pierrepont Street, Brooklyn, with his son-in-law (a watch importer), his daughter, and two female Irish servants.

We also know some information about Carl Magnus Spangburg, memorialized on the Weehawken Monument as Charles Sponberg. Anna Sophia Spangburg, mother of 3rd Assistant Engineer Carl Magnus Spangburg of the Weehawken, applied in 1866 for a pension, based on her son’s service and death. According to a letter from the Navy Department, Charles was appointed on April 28, 1863, and ordered to the U.S. S. Mercedita, from which he transferred to the Weehawken on August 15. A letter from the Legation of Sweden and Norway, in support of her pension application, states that his mother was a Swedish citizen and Carl was her only child. However, his mother’s application was rejected on the grounds that her husband was “not physically incapable of supporting his wife.”

This monument has stood along Green-Wood’s Central Avenue for 144 years. Few have been aware of its existence, let alone the story behind it. Hopefully the above will call attention to it, honoring the ultimate sacrifice that these four men made in the service of their country.

Dear Mr. Richman,

Fortuitously, I stumbled upon your Green-Wood blog entry concerning the grave site of the USS Weehawken engineers. While working several years ago on a project to document the archaeological vestiges from the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield, I had attempted to track down the whereabouts of the remains recovered from Weehawken. As mentioned in the New York Daily Tribune article of the funeral it appeared that the remains were buried at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Cemetery. Then I found a recent news article online reporting the removal and re-internment of the graves at the BNYC in the mid-1920s to Cypress Hill National Cemetery. I contacted the office there requesting any information about the Weehawken engineers but they did not have any information. I then assumed perhaps they were lost from memory. So today I was happy to find and read your blog article with information and pictures about the grave site commemorating those four engineers at the Green-Wood Cemetery.

Concerning the wreck itself, it is buried under several feet of overburden with substantial amount of structure still remaining, most likely only the lower hull with the major components, that is the turret, engines, boilers, armored deck, etc. recovered during the 1870s salvage operations.

We dove on the other Passaic-class monitor sunk at Charleston Harbor, the USS Patapsco struck by a mine in early 1865, that caused a substantial loss of life. The remains recovered during 1870s salvage operations at this monitor were buried at Ft. Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, again under a monument. All that remains of Patapsco is the lower hull, with the forward berth deck iron beams still intact, but everything from the turret area to the stern is badly broken up. They did quite a thorough job of recovering the valuable metal components of the monitor, although there are a few 15-in balls lying around here and there.

In any event, I am glad to see that a grave site still exists for these casualties from the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield, and quite happy to find the fruits of your inquisitiveness to help fill in the history surrounding the sinking of the USS Weehawken.

Sincerely,

Jim Spirek

State Underwater Archaeologist

South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology

University of South Carolina, Columbia

Thanks, Jim, for sharing this fascinating update.