PABST (or PAPST), JACOB (1832-1881). Private, 52nd New York Infantry, Company I. Of German birth, he enlisted at New York City on October 5, 1861, and mustered into the 52nd on November 1. As per his muster roll, which used the name “Papst,” and the Report of the Adjutant General, he deserted at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, on an unspecified date.

On April 28, 1866, Pabst became a naturalized citizen; his documentation states that he was in the restaurant business and lived at 172 Eldridge Street in Manhattan. Pabst is listed as working in beer at 308 Broadway in the 1867 New York City Directory. As per the 1870 census and the 1870 New York City Directory, he was a saloon keeper at the same Eldridge Street address. The 1876 New York City Directory lists him working in beer and living at 58 Lispenard Street. As per the 1880 census, he lived with his wife and daughter in Manhattan at the same Lispenard Street address and was in the restaurant business. His last residence was 58 Lispenard Street, New York City. His death was attributed to pyemia, a form of blood poisoning. Section 165, lot 16943.

Civil War Bio Search

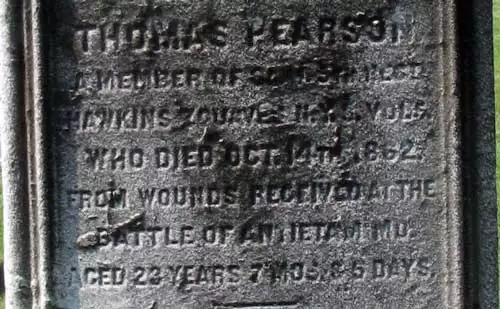

PABST (or PAPST), JACOB (1835-1862). First lieutenant, 20th New York Infantry, Companies G and D. A native of Dürkheim in Bavaria, Germany, Pabst married Caroline Leonhardt on July 1, 1858, at the United German Church in New York City. During the Civil War, he enlisted at New York City as a second lieutenant on May 3, 1861, and was commissioned into the 20th New York’s Company G three days later. Pabst was promoted to first lieutenant on May 1, 1862, and was transferred that day to Company D. On September 17, 1862, he was killed in battle at Antietam, Maryland. His death was attributed to a gunshot wound (vulnus sclopet). Originally interred at Antietam National Cemetery, gravesite 652, Pabst’s name was later noted on the Bodies in Transit List for shipment through New York City for re-interment at Green-Wood. His name is listed on the Register of Deaths of Volunteers from New York, 1861-1865. On October 20, 1862, Caroline Pabst applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 11,050. Caroline and her son, Jacob Pabst, who are buried at Lutheran All Faiths Cemetery in Queens, have their headstone inscribed, “Civil War Widow & Orphan.” Section 115, lot 13536 (Soldiers’ Lot), grave 18.

PACKARD, HENRY O. (1845-1872). Corporal, 13th New York Heavy Artillery, Company F. Packard was born in Saratoga, New York. The 1860 census reports that he lived in Ballston in Sarasota County with his parents and siblings. As per his soldier record, Packard enlisted as a private on January 6, 1864, at Stillwater, New York, was promoted to corporal on January 15, and mustered into Company F of the 13th New York Heavy Artillery on January 31. The “Town Clerk’s Register of Men Who Served in the Civil War” from Saratoga, New York, notes that Packard received a bounty of $300 after his enlistment. His muster roll, which reports February 18 as the date he mustered into his company, indicates that he was a clerk who was 5′ 6″ tall with grey eyes, brown hair and light complexion. On July 18, 1865, Packard mustered out at Norfolk, Virginia.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that Packard married Ida Bassford at her home on January 3, 1868. At the time of the 1870 census, he lived with his wife and daughter in Caroline, Tompkins County, New York, and worked as a clerk in a butter factory. That same year, he was listed as a clerk in the Brooklyn Directory for 1870; his home address was 231 Schermerhorn Street. Packard’s death certificate notes that he was a clerk. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, newspapers in Tompkins and Saratoga Counties were asked to print notices of his death. His last residence was 484 Adelphi Street in Brooklyn. His obituaries in the New York Herald and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle state that he died “after a long and painful illness” (consumption). Ida Packard applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1880, certificate 235,957. The Veterans Census of 1890 for Caroline in Tompkins County was completed by Ida Packard as his widow; it was noted that his discharge papers had been mislaid. Section 92, lot 4135.

PADDOCK, CHARLES HENRY (1843-1923). First lieutenant, 157th New York Infantry, Companies C and D. A native of Hamilton, New York, in Madison County, the censuses of 1850 and 1860 report that Paddock lived there with his parents and siblings. The 1850 census reports that Hiram Paddock, his father, was a farmer whose real estate was valued at $6,900; the 1860 census reports that Hiram Paddock was a merchant whose real estate was worth $5,000 and whose personal estate was valued at $1,500. During the Civil War, Charles Paddock enlisted at Hamilton, New York, as a first sergeant on August 22, 1862, and mustered into the 157th New York on September 19, 1862. The “Town Clerk’s Register of Men Who Served in the Civil War from Hamilton, New York,” notes that Paddock received a bounty of $50 after his enlistment and that he participated at the Battles of Chancellorsville, Virginia, and Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

In these series of letters, Paddock describes his involvement in the Gettsyburg Campaign and its aftermath. Paddock wrote this letter to his brother from Littlestown, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1863.

DEAR BROTHER GENE:

It is some time since I have written you. I am very sorry so long a time has elapsed, and…an apology, I will try to give you an account of my travels. Saturday, at 2 P.M., about 1,000 men from all Corps left…Camp Distribution with happy hearts, and went down to Alexandria and took the boat for Washington, where we arrived about dusk. Sunday morning we took the cars and passed the Relay House at noon, and Monday morning we were in Frederick. When I got down in the city I found the army passing through, and that the 11th Corps was about half an hour ahead. So I pressed on with vigor and by noon had left the 12th A. C. far behind, and had got far up into the 3rd A. C., when to my great dismay I found the 11th A.C. had turned off on another road to the left, and after weighing the matter well, I concluded to keep on with this Corps, thinking the roads would meet again. So I continued on to Torrey Town, where we halted that night. I had a nice bed in a barn, which I assure you I improved to the best possible advantage, for I had marched 25 miles and was footsore and lame. In the morning I awoke much refreshed, and found the 12th A. C. took the advance.—So I kept in front with them to Littlestown, (9 miles) and having arrived there we found considerable excitement existing, from the fact that the rebel cavalry were two miles out of town in the woods, and that they had fired on our cavalry killing a number of them. However we came on as far as here [2 miles] and halted. Last night I slept on the ground. But the signal has been given to fall in, so I must close by saying that my health is excellent, and that such nice weather for marching we have never had. If I have an opportunity to-day I will mail this. The country we are marching through is beautiful, and seems like home compared with old Virginia.

Wednesday 2 P.M.…I am now 2 miles from Gettysburg. They are fighting very…I left the 12th A. C. 2 miles back, and have just stopped and eat dinner by a …picket in the road here. About…rebel prisoners have just gone by, and…are a lot more coming. Our Corps…splendid thing in taking them. It is…advance now, and I shall see fighting. It is now 5 P.M., and what I have…through in the last two hours it will…much longer to relate.

Paddock went on to relate his experience in battle:

Thursday, July 2nd, 8 A.M. I was …to stop last night, for the robs or-…us on to this place, where we lay tonight. Yesterday, after writing, I left…picket and came through the town and…the 157th supporting the Brigade…ry. I had just got there when we were ordered forward. The battery was…ing finely, and we went to the front a little to the left, when we saw they were flanking us on the right and rear. So…changed front and went forward to…t them in that direction, and were…right up in a wheat-field. There was a single brigade against the 157th at a very short distance. Several different boys fell by my side. It was here that Lieutenant Col. Arrowsmith fell, and died immediately, hit in the head and chest. By. Fitch was wounded, and Lieut. Coffin fell, wounded in the back. Seeing that it was useless to…d against such odds, we were ordered to retreat, and we fell back out of immediate range. I got pretty near the town, where I was helping carry Adj. Henry, when a ball came hitting two of us, and we were obliged to leave him in the edge of town. The Reg’t rallied for some time, but the rebels did not advance there, but were rushing around to cut off our rear. There were but six men of my Co. left including officers. The Col[onel] was there and the colors all right. I was so tired that I could not stand up. Seeing the rebels were getting in the south part of the town we were ordered to retreat in that direction, and such a confusion and hubbub it is hard to imagine. When we got into the center of the town the bullets commenced whistling up and down the streets, and we were ordered to take to the houses. In a few minutes the streets were full of rebels. I was in a garden with a lot of the 1st Corps boys, and the first thing I knew a grey back was ordering us to take off our cartridge boxes, stack guns, & c.—Then they marched us to the rear, where I was writing last night, and not far from the wheat field. Lieut. Coffin came up last night; he said a ball passed through his blanket-roll across his back, coat and belt, and made a hole in his pants large enough for me to put three fingers through, but did not break the skin, though he supposed the ball was in him until a short time before he got here. He washed the blood off from Arrowsmith’s face and brought away his sabre and scabbard and belt, &c. He begged the rebs to let him stay but they would not. The last I saw of Col[onel] Brown, he was going up the street with the colors by his side as fast as possible.—There must be 4,000 of us here. We moved a mile further from town this morning. There they offered to parole us and keep the officers. Most of the Reg’ts accepted it, and while we were disputing about it, a heavy fire opened about three miles off on our right, which hits kept coming nearer and nearer, and now there is a battery opened on us not more than a half a mile off. The rebs scatter to the rear like sheep, but some are wounded.

Friday, 5 P.M. I have just passed through a fiery ordeal. That parole our officers did not like at all. But they were all separated from us yesterday. Well, today the question came to each Reg’t in turn. All the boys wanted to know what I was going to do; for you see I am the ranking non-commissioned officer, and have them all to see to.

Paddock goes on to relate his hardships as a prisoner of war:

July 5th. Yesterday was the Fourth. We marched a long distance and it rained a perfect flood. It was awful but not very cold. When we halted last night we cooked up a few flour cakes and roasted some beef on sticks, after disposing of which and putting on some dry clothing, which I was so extremely fortunate as to have in my knapsack. I laid down; but I was soon waked up by one of the boys to draw the rations. After waiting about two hours I obtained a pint and a half of flour per man, but the 1st, 3rd and 5th Corps boys got all the beef. The officers march just in front of us, and come back occasionally to see how we are getting on.

Monday morn. I can’t realize yesterday was communion at home, for we suffered the hardest marching we have ever had to endure. We started about 8 A.M. The order came before most of us were up. My breakfast consisted of one flour cake the size of my hand, my dinner of hard tack, my supper one canteen of water. We marched until 11 P.M., and are now up on a mountain. Lieut. Coffin is sick. Capt. Place looks as haggard as a ghost. There is a heavy fog and mist wetting us through and making it impossible to look three rods ahead.

Tuesday, P.M. We marched down the mountain several miles in a south-westerly direction to Waterloo and drew rations. At 5 0’clock we were on the march again but something kept halting the column every few rods, so that at one time we made only one mile in two hours. We passed through Waynesboro at 9 p.m., and no signs of camp. We were then marching tolerably fast, but at 11 we commenced that halting again, and finally they made a halt of half an hour, and in a jiff every man was in a snooze. I never suffered so much from mere sleepiness as last night.—At half past twelve we passed Hagerstown. I did not believe they would march us all night, until it began to grow light this morning. It was moonlight and fine marching. The guards are rough as Indians generally, but they divide their last ration with the prisoners. We arrived here—two miles from the river—at 1 p.m.

Thursday, July 9th. It is a beautiful morning. I did not write yesterday, but will try to do so more regularly hereafter. Yesterday we drew no rations until evening, and we were getting pretty hungry I assure you. The boys exchange all kinds of clothing and trinkets for bread. A cake of bread the size of a round pie can hardly be bought for a dollar. I exchanged my wallet for a piece. My shoes are most gone, and I shall be obliged to go barefoot soon. We expect to cross the river today; we should have crossed yesterday but their pontoons were burned.

Friday morn. Once more have I enjoyed the peculiar bliss of resting my weary limbs on the sacred soil of Virginia. We crossed the river at 10 P.M. yesterday.—It was a slow process, having nothing but ferry boats to use. There are some of the boys behind yet, A lady gave me a shortcake in Williamsport just before we crossed. I found a man from the 90th P[ennsylvani]a. V[olunteers], that took off the Lieut[enant] Col[onel]’s shoulder straps. He obtained them just before the rebs came up searching the dead. He would not part with them at first, but finally consented to take a dollar for his trouble and let me have them. The Col[onel] will value them highly, for there is a bullet hole in one of them, cutting off half the leaf.

Saturday Morn. We are on the march again without any thing to eat. It is 60 hours since we have drawn rations. We then drew 6 oz. flour and one lb. of beef per man. We started yesterday at 12 M. and arrived at this camp, two miles beyond Martinsburg after dark; being a distance of 15 miles. I am getting very weak. I have a bad diarrhea, the result of eating beef without salt, and these heavy flour cakes, & c. Yesterday as we came thro’ Martinsburg, the ladies cheered us, and hoped us back again soon, all right &c. They would have brought us out bread, but the guards would not let us go and get it, nor allow them to come and bring it to us. But finally they commenced handing it to us between the guards.

Twelve miles from Winchester, 3 P.M. Dear Bro. I was sick this morning, and after marching a while, sat down by the fence with a severe cramp in my bowels, feeling pretty blue. Soon a guard came along and after looking well into my face, handed me a piece of bread, hoping it would help me. I devoured it greedily and soon caught up, feeling much refreshed. We arrived here about 12 M., and for dinner obtained a small piece of bread and beef each.

After Paddock was captured at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863 (the date on his soldier record, which was the first day of that three-day battle), he was sent to Belle Island in the James River opposite Richmond, Virginia, for three months as a prisoner of war until he was paroled on September 24, 1863, and then was sent to the front at Charleston, South Carolina. On December 17, 1863, he was promoted to first lieutenant. His hometown records indicate that he served at Fernandina, Florida, and was in charge of prisoners at Fort Pulaski, Georgia. According to his pension record, he was transferred intra-regimentally to Company D on June 24, 1864. He mustered out on July 10, 1865, at Charleston, South Carolina.

As per his passport application of April 7, 1883, for a trip to Europe, he was 5′ 10″ tall with a high forehead, rather large mouth, hazel brown eyes, medium nose, slightly receding chin, dark hair, dark complexion and oval face. On April 17, 1883, Paddock married Ella Louise Murphy. The 1890 Veterans Schedule confirms his Civil War service. The 1891 New York City Directory lists Paddock as working in dry goods at 340 Broadway; his home address was 141 West 70th Street. The federal census of 1900 and the 1905 New York State census report that he lived with his wife, children and three servants (cook, maid, waitress) at 141 West 70th Street and worked in dry goods. The 1910 census notes that he was living on West 72nd Street with his sister-in-law and her family. Paddock applied for and received a pension in 1913, certificate 1,171,834. As per his obituaries in The New York Times and the Evening Telegram, which confirm his Civil War service, he was a retired wholesale dry goods merchant. A trustee of the Park Avenue Baptist Church, he was also a charter member of the Old Settlers’ Association of the West Side and a member of the Loyal Legion, a patriotic organization of men who served as officers in the Civil War. His death certificate indicates that he was a widower and a dry goods merchant; his wife died in 1918. He last lived at 149 West 72nd Street, in New York City. His death was attributed to pneumonia. On November 22, 1923, a listing in The New York Times states that Paddock left an estate valued at $31,988 to his two sons and two daughters. In 2009, a collection of his property, including a drill rifle, printed correspondence, and photos, was sold on eBay. Section 56, lot 5849.

PADLEY, WILLIAM H. (1832-1870). Private, 134th New York Infantry, Company H; 10th Veteran Reserve Corps. Padley, who was born in England, enlisted on August 25, 1862, at Schenectady, New York, as a private, and mustered into Company H of the 134th New York on September 22. As per his muster roll, he was a farmer who was 5′ 5″ tall with blue eyes, brown hair and a florid complexion. Padley’s muster roll notes that he was absent and hospitalized at Central Park, New York, on April 10, 1863. On July 1, 1863, he was transferred into the 10th Veteran Reserve Corps. He was discharged on June 29, 1865, at Washington, D.C. As per the census of 1870, he lived in Brooklyn with his wife and son and worked as a porter; he was also listed as a porter in the 1870 Brooklyn Directory. His last residence was 520 Court Street in Brooklyn. He died from congestion of the brain. Lot 17931, grave 260.

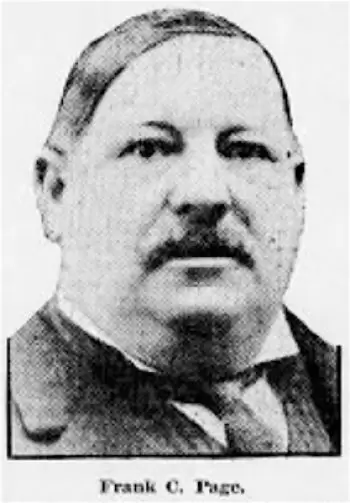

PAGE, FRANK C. (1849-1915). Musician, 169th New York Infantry, Company F. A native of Worchester, Massachusetts, his birth record indicates that his first name was Christopher, his father’s name. Page said he was 15 at the time of his enlistment as a musician at New York City on July 15, 1862, but was only 13 years old when he mustered into the 119th New York on September 4; his obituaries in the New York Sun and the Brooklyn Standard Union incorrectly state that he served in the 169th New York. As per his muster roll, he was a laborer who was 4′ 7″ tall with gray eyes, light hair and a light complexion. He served as a drummer boy and, according to his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was at the Seven Days Battle in Virginia. During that engagement, Page received a hand wound that left him with a permanent scar. Although his soldier record indicates that he was discharged for disability on January 7, 1863, he either re-enlisted or exaggerated his service history because his obituaries in the New York Sun and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle note that Page was presented with a medal for bravery at the Battle of Gettysburg and served throughout the Civil War—both of which would have been impossible if he last served on January 7, 1863.

As per the 1865 New York State census, Page lived in Brooklyn with his parents and sibling and was not employed. He studied architecture and became a pioneer hotel builder in Rockaway Beach, New York, beginning in 1876. The 1880 census notes that Frank Page and his father were living in Brooklyn with his sister and her family; all of the men in the family were listed as carpenters. On October 4, 1883, he married Elizabeth Myers, the daughter of Samuel Myers (see), a United States marshal during the Civil War and New York City alderman; Myers and Page were both involved in the hotel industry in Rockaway. Page was the owner of the Pier Hotel, Iron Pier, and Vienna Hotel, and several stores in Rockaway. The Brooklyn Directories for 1889 and 1890 list him as a hotelier in Rockaway Beach and the 1892 New York State census lists him as a carpenter. He was also a charter member of the Sam Myers Hook and Ladder Company and the Veteran Volunteer Fire Department of Rockaway Beach. His obituaries in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the Brooklyn Standard Union, which confirm his Civil War service, note that he was also a member of Rockaway Beach Aerie, Order of Eagles, a fraternal organization that provided sick benefits, life insurance, etc. On June 7, 1884, he mustered into the Mansfield Post #35 of the G.A.R.; he listed his occupation as hotel keeper and attributed his service to the 119th New York. In addition, he was an attendant at the Universalist Church of Our Father at Grand Avenue and Lefferts Place in Brooklyn.

Page received an invalid pension in 1900, certificate 1,078,569. As per the census of 1910, he was a carpenter and house builder. Page’s death certificate notes that he was married and was a proprietor. He last resided in Brooklyn at 691 Nostrand Avenue; his obituary in the New York Herald indicates that he lived there for 45 years. His obituary in the Sun attributes his death to pneumonia resulting from a compilation of diseases. There is a G.A.R. ribbon carved into his gravestone attesting to his membership in the Mansfield Post #65. His widow, Elizabeth Page, who is interred with him, received a widow’s pension in 1915, certificate 794,127.

As per an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on April 24, 1915, Page left the bulk of his estate to his son, Samuel, the executor of his will. Samuel Page was left his father’s personal estate and the Iron Pier and all of the buildings and the contents therein on that property; the property would then be left to Samuel’s heirs. His wife, Elizabeth, was bequeathed $500, the same sum bequeathed to his sister; his daughter, Idella Koeschel, was left $1,200 and her grandfather’s gold watch. Apparently, Elizabeth Page had a share of her husband’s property because an article in the Rockaway Beach Wave on November 5, 1915, notes that she leased the Vienna Hotel in Rockaway for three years for $1,800 per year; her son, Samuel, leased a storage building on the Iron Pier for three years at $1,800 per year. (Samuel Page died in 1917.) Section 137, lot 29103.

PAGE, JOHN MILTON (1840-1931). Corporal, 40th New York Infantry, Companies E and D. He enlisted as a private at Yonkers, New York, on June 14, 1861, and mustered into Company E of the 40th New York, known familiarly as the Mozart Regiment, on that date. Page was promoted to corporal on June 1, 1862, wounded at Chantilly, Virginia, on September 1, 1862, transferred to Company E on May 25, 1863, and discharged for disability on April 30, 1864, at Washington, D.C. According to his obituary in the Hempstead Sentinel, he was, at the time of his death, Long Island’s oldest veteran of the Civil War. That obituary noted that Page fought in many engagements of the Civil War, was wounded at Second Bull Run, Virginia, but returned to service after his injury. A purchasing agent by trade, he last lived with his son at 166 Cleveland Avenue in Rockville Centre, Long Island. His cause of death was pulmonary edema (excess fluid in the lungs). Section 90, lot 12040.

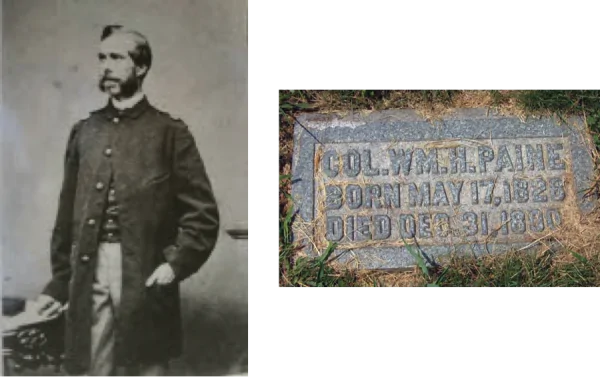

PAINE, WILLIAM HENRY (1828-1890). Colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major by brevet; captain and additional aide-de-camp, United States Volunteers. Born in Chester, New Hampshire, to an old New England family, Paine studied engineering and first worked at age twenty as a land surveyor in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. He then ventured to California at the time of the Gold Rush, where he introduced new engineering techniques while engaged in the mining industry. In 1849, he surveyed a road across the Rockies and, in 1853, surveyed a road for a Pacific railroad traversing the Nevada Mountains from Sacramento, California, to Utah. As per his biography for his papers at the New-York Historical Society, he returned to Sheboygan in 1856 where he invented steel surveyor’s measuring tape, a product he patented in 1860.

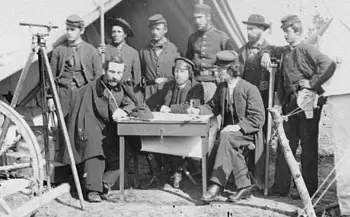

As per his obituary in The New York Times, Paine raised several regiments of Wisconsin troops during the Civil War, accompanied the 4th Wisconsin to Washington, D.C., then entered the Engineer Corps. His biography for the New-York Historical Society reports that he worked as a topographical engineer for the Union Army in 1861, mapping projects in Washington, D.C., and in Virginia. Paine enlisted as a captain on April 28, 1862, and was commissioned that day into the United States Volunteers as a captain and additional aide-de-camp. The Times obituary notes that he was more than once thanked by President Abraham Lincoln for the valuable information he obtained regarding the dimensions of the railway bridges linking Washington and Richmond, Virginia, many of which had been destroyed by Confederate rebels; these dimensions were necessary to secure the movement of Army materiel in advance of their reconstruction. As per Earl B. McElfresh in Maps and Mapmakers of the Civil War, Paine attracted President Lincoln’s attention when he risked his life to help the War Department secure information about status of the aforementioned bridges by donning civilian attire and making his way to northern Virginia and back to scout the area.

Paine, who had been the assistant to General Amiel W. Whipple, the chief topographical engineer to the Federal Army of Northern Virginia, was appointed a captain of engineers by the President, a rare appointment for a non-West Point soldier. He was appointed captain on the staff of General Irvin McDowell and commended for his superior knowledge of topographical engineering and unequalled skill at drafting military maps. According to McElfresh, topographical engineers were well trained and very artistic, exhibiting an understanding of color and composition as well as fine technical skill. Paine’s pencil maps were considered exemplary for their accuracy and reliability. His New York Times obituary notes that he furnished maps to Generals Ulysses S. Grant, Andrew Humphreys, and John W. dePeyster, and to Horace Greeley and other writers. Major General Pope, United States Volunteers, in his report on January 27, 1863, describing the recent campaign in Virginia, gave honorable mention to his staff and to Captain Paine, who was “zealous, untiring, and efficient” in executing duties that were particularly arduous.

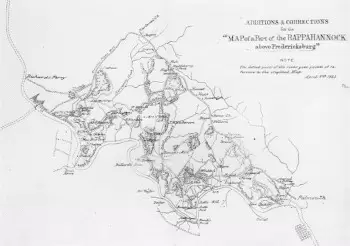

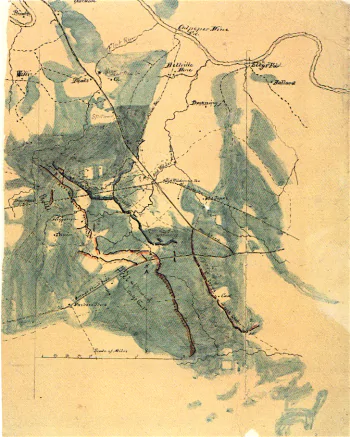

Paine’s obituary in Engineering News relates a story that Paine was assisted by his “colored body-servant,” Darney Walker. Walker, who had a topographical “instinct,” relayed information from a Confederate camp across the Rappahannock, near Fredericksburg, Virginia, through his association with a washerwoman. That woman would relay signals to Walker by arranging clothes in different colors and positions on a clothesline; the secret code was known to the two, and the information then relayed to Paine. This topographical map (below) on April 3, 1863, drawn quickly by Paine of the bank of the Rappahannock above Fredericksburg, Virginia, helped Union General Joseph Hooker “steal a march on General Robert E. Lee” three weeks later. Hooker was able to cross upstream at Kelly’s Ford and came down on the flank of Lee’s Army, and advance closer to Richmond than Lee.

On June 4, 1863, Paine teamed with another topographical engineer and non-West Point graduate, Washington Roebling, in riding in an observation balloon across the Rappahannock River, reporting on the first stirrings of the Confederates signaling the onset of the Gettysburg campaign. The two recognized that the Union was caught ‘flat-footed” in respect to maps when the Confederates began its second invasion of the North. McElfresh contends that part of the problem was caused by changes in the Union command and “complacency at the army’s map headquarters” (p. 253). Paine later assisted Major General George G. Meade, a former topographical engineer who had just been elevated to command of the Army of the Potomac, in preparation for the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. At midnight, on July 1, 1863, Paine escorted Meade on a tour of the battlefield to acquaint the general with the locale and to prepare to map it. On May 5-6, 1864, Paine’s map of the Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia, (below) was significant because it documents the first contact between General Ulysses S. Grant, commanding Union forces, and General Robert E. Lee, leading the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Paine highlighted the positions of different Confederate corps and drew in a broken arching line that marked the unfinished railroad. Lee wanted to fight in this area because the tangle of woods neutralized the numeric advantage of the Union Army, especially the artillery. McElfresh stated that Paine obtained data for this sketch (the first of three) from notes taken on the region in the late 1820s by R.C. Taylor, an employee of the State Geological Survey of Virginia.

Paine’s maps of the Richmond area detailed woods, riverbanks and road services and included annotations. On August 1, 1864, he was brevetted major of United States Volunteers for “faithful and meritorious services in the field.” His promotions by brevet to lieutenant colonel on March 2, 1865, and to colonel on April 9, 1865, were awarded for “gallantry and meritorious services during the recent operations resulting in the fall of Richmond, Virginia, and the surrender of the insurgent army under General Robert E. Lee.” Paine mustered out on August 5, 1865. In addition to McDowell, Pope, Hooker and Meade, Paine also served on the staff of General John C. Frémont.

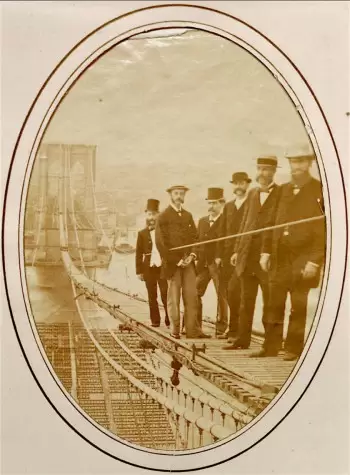

After the Civil War, Paine drew maps for such Civil War history publications as William Swinton’s (see) History of the Army of the Potomac and Horace Greeley’s American Conflict. As per his obituary in The New York Times, Paine was one of the foremost engineers in the country. In the late 1860s, he worked for the Flushing Railroad. In 1869, he was chosen as one of the engineers on the Brooklyn Bridge and assisted John A. Roebling (father of Washington Roebling, with whom he had worked in 1863) in making the original surveys. Paine was working with John Roebling on June 28, 1869, to determine the exact location of the Brooklyn tower when a ferry crashed into a piling where Roebling was standing, crushing Roebling’s toes; tetanus set in after medical help was refused and Roebling died on July 22. His son, Washington, then took over leadership of the project. Paine superintended the placing of the two caissons, built the New York tower, and was in charge of laying the cables that would support the structure. He invented a grip for use on the railroad cars and planned the system of cable traction on the bridge; in all, he received 14 patents for cable railway work during his tenure with the Brooklyn Bridge.

After remaining with the Brooklyn Bridge as an assistant engineer for several years, Paine then opened an office in New York City as a consultant for cable railroad enterprises. He was responsible for the plans for the Tenth Avenue and 125th Street cable roads in New York City and proposed plans for a Third Avenue cable road. Subsequently, he went to Kansas City and Omaha, Nebraska, to superintend construction of cable roads. After laying cables in San Francisco, California, and Denver, Colorado, he came to Cleveland, Ohio, in August 1889 to take charge of the Cleveland City Cable Company’s twenty miles of roadways, a project that was completed one week before his death. In 1889, he applied for an invalid pension, application 325,813, but apparently he died before it was certified. As per his obituary in Engineering News, about 30 members of the American Society of Civil Engineers, of which Paine had been a member since 1875 and a president, attended his funeral at the Church of the Puritans in Harlem. Members of Hamilton Post #182 of the G.A.R., the Harlem Republican Club, and engineering associates who worked with him on the Brooklyn Bridge also attended his funeral. That obituary praised him “as a most useful citizen, valiant soldier and engineer endowed by nature, and quickened by long training, with those qualities that make him eminent in his profession.” He last lived on West 122nd Street in Manhattan. Brooklyn Bridge trustees planned to honor him after his death was announced. Although his obituary notes that he suffered from chronic stomach trouble, he died in Cleveland, Ohio, of heart disease. Catharine Paine applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 777,865. Section 139, lot 27537.

PAISLEY, JOHN (1831-1889). Captain, 10th Ohio Cavalry, Companies B and A; first sergeant, 85th Ohio Infantry, Company F. Born in Ireland, Paisley enlisted on May 29, 1862, as a first sergeant, mustered into Company F of the 85th Ohio on June 10, and mustered out on September 23, 1862, at Camp Chase, Ohio. He then re-enlisted on October 13, 1862, was promoted to first lieutenant of his company on November 7, and was commissioned into Company B of the 10th Ohio Cavalry on February 10, 1863. On March 17, 1864, his promotion to captain became effective upon his transfer to Company A that day. He served in that capacity until his discharge on July 24, 1865, at Lexington, North Carolina. He last resided on Lafayette Street in New Rochelle, New York. His death was attributed to cardiac paralysis. Section 189, lot 17030.

PALMER, FRANCES FLORA BOND PALMER (1812-1876). Civil War artist and lithographer. Born in Leicester, England, Frances (Fanny) Flora Bond was educated there at a private school for women where she learned to draw. She married Edmund Seymour Palmer, a man’s servant, at age 20, and they had two children. The couple fell into financial trouble after Edmund lost his job; Fanny set up a lithography business in Leicester in 1842, where she was the artist and her husband, the printer. The business failed but in 1844, the Palmers immigrated to America and settled in New York City where they set up a lithography business that bore the name F & S Palmer and produced floral prints for The American Flora by A. B. Strong. She also produced lithographs of the Mexican War, demonstrating her ability to draw a variety of subjects. Although the Palmers produced a book in 1849, The New York Drawing Book: Containing a Series of Original Designs and Sketches of American Scenery, No. 1, that sold for only 25 cents, both the book failed to sell and the business failed to flourish. Fanny Palmer then gave singing lessons and worked as a governess while her husband opened a tavern.

However, the family’s fortunes changed in 1851 when Palmer was hired as a staff artist by Nathaniel Currier; in 1857, when James Ives (see), Currier’s brother-in-law, joined the firm, the establishment thereafter was known as Currier & Ives. As per Maggie MacLean in her blog, Civil War Women (2014), Ives, an artist, often redrew the figures on Palmer’s work, but, because she needed the money, she remained in her position at the firm. Palmer distinguished herself as an artist at a time when art was not considered an appropriate profession for a woman and is credited with developing a lithographic crayon. During her years at Currier & Ives, she produced more prints than any other artist, a considerable achievement in that field. At first, she sketched rural and suburban settings in New Jersey and Long Island, traveling there by carriage and using descriptions in books, daguerreotypes and later, other types of photographs, for her subjects. Tragedy struck the family in 1859, when Edmund Palmer, who had relied on Fanny to support the family, died after he drunkenly fell down a flight of stairs in a Brooklyn hotel leaving Fanny as the sole support of her children, grandchild and sister. In 1862, she published Landscape, Fruit and Flowers, highly regarded for its color lithography. She flourished at her work which encompassed landscapes, drawings of railroads, and scenes of sports and marine life. Her skills were recognized as an artist of clipper ships, yachts and steamboats.

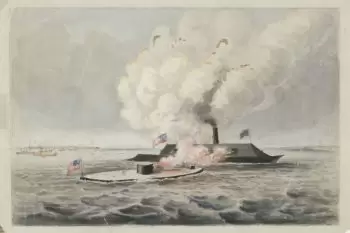

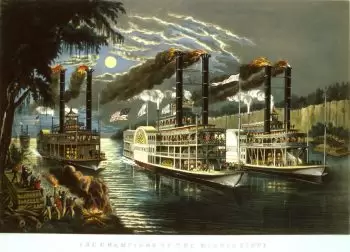

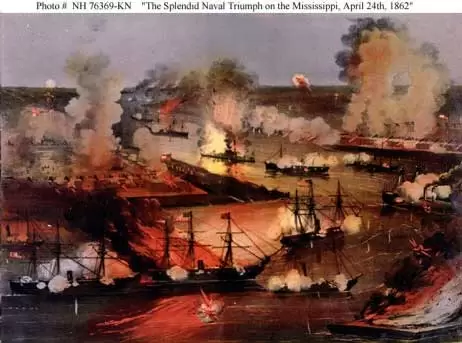

Palmer’s work as a Civil War artist of naval scenes has only recently been recognized and celebrated. Indeed, in the Union Image by Mark Neely and Harold Holzer, they conclude that Fanny Palmer “barely missed becoming the most important image maker of the Civil War” not due to any failure on her part, but rather because Currier & Ives never commissioned her to compose any on-land battle scenes. As per Fanny Palmer: The Life and Work of a Currier & Ives Artist by Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, Palmer’s print, Staten Island and the Narrows (1861) depicted a New York view and an image of the City’s harbor defenses. She was most renowned for her prints of the battle of the Monitor v. Merrimac (1862) at Hampton Roads (see image below). Rubinstein notes that Palmer’s print showed the world that the United States was in the forefront of modern engineering for naval engagements. In 1865, Palmer depicted The Victorious Attack on Fort Fisher, North Carolina (January 15, 1865) when Confederate supply lines were cut off. She also made prints of three Union military camps, The Valley of the Shenandoah (1864), Cumberland Valley, from Bridgeport Heights Opposite Harrisburg, Pa. (1865), and Harrisburg and the Susquehanna, From Bridgeport Heights (1865). Those works, which showed orderly rows of tents, helped ease the worries of soldiers’ families because of their calm panoramas. In the waning months of the Civil War, Palmer created two contrasting image of Mississippi, one in time of peace and the other in time of war (see image of prosperity below).

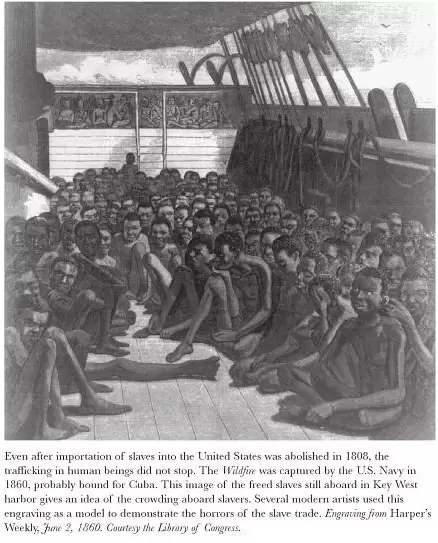

After the Civil War, Palmer collaborated with Ives on lithographs showing images of American life, among them the transcontinental railroad, westward expansion and life on the Mississippi as it was affected by the river’s flooding. Critics debate the reasons why African-Americans in the prints about the Mississippi life appeared in stereotyped images; Palmer’s original drawings were not stereotypical and perhaps the final images were meant to appeal to a mass audience in the South and to Northerners who feared that the freed slaves were gaining too much power. She retired from Currier & Ives in 1868, leaving a legacy of more than 200 lithographs. Many of her prints were unsigned or bore the initials F. F. Palmer. She last lived with her sister; her daughter was also an artist. Palmer’s death was attributed to tuberculosis. Section 58, lot 4659.

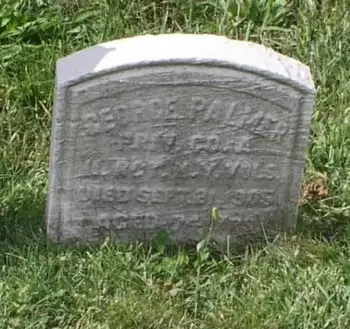

PALMER, GEORGE E. (1831-1905). Sergeant, 4th New York Heavy Artillery, Battery G; private, 11th New York Infantry, Companies A and I. A native of England, Palmer enlisted on April 20, 1861, at New York City, mustered into Company A of the 11th New York on May 7, and transferred to Company I on October 11, 1861. He mustered out at New York City on June 2, 1862. Later that month, on June 13, 1862, Palmer mustered into the 4th New York Heavy Artillery as a sergeant at New York City. As per his muster roll of August 1863, Palmer was found guilty by General Court Martial of violation of the 6th and 9th Articles of War and sentenced to hard labor on Government works for the balance of his term. Article 6 prohibits disrespect toward a commanding officer and Article 9 prohibits violence or threat of violence toward a superior officer. Palmer mustered out at New York City on June 17, 1865; according to a letter from the Department of War dated March 24, 1865, he was to be given a dishonorable discharge.

As per the 1870 federal census and 1875 New York State censuses, he lived in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, with his wife and children and was employed as a plumber. The 1880 census notes that the Palmer family still lived in Greenpoint and that George Palmer and one of his sons worked in plumbing and gas. The 1889 Brooklyn Directory lists him as a plumber at 63 Greenpoint Avenue; his home address was 139 Calyer Street. The Veterans Census of 1890 confirms Palmer’s Civil War service. In spite of the aforementioned court-martial and apparent dishonorable discharge, Palmer applied for and received an invalid pension in 1891, certificate 797,074. According to the 1892 New York State census, he was listed as a plumber living in Brooklyn. In 1901, he was admitted to the Home for Soldiers’ and Sailors’ in Bath, New York, from September 13 through October 15. At that time, he was a widower who identified his occupation as “paper stainer.” He was 5′ 5″ tall with blue eyes, grey hair and a sandy complexion suffering from heart and hearing problems in addition to dementia. As per his death certificate, he was a widower and a machinist by trade. His last residence was at 112 North Elliot Place in Brooklyn. He died from apoplexy. A government-issued gravestone was ordered for him early in the 20th century. Section B, lot 8575, grave 496.

PALMER, HOYT (1819-1879). Second lieutenant, 10th Veteran Reserve Corps, Company A; sergeant, 1st United States Veteran Infantry; corporal, 2nd United States Artillery, Company C. Palmer, a Chittenton, Vermont, native, first served with the United States Army. He enlisted on September 7, 1848, listed his occupation as soldier and described himself as having hazel eyes, black hair and a sallow complexion. Assigned to the 2nd Artillery, Company L, he was discharged on September 24, 1853, at the expiration of his service. The 1850 census notes that he was a Florida resident and a sergeant in the United States Army. As per the 1855 New York State census, he lived in the New Utrecht section of Brooklyn and worked as a druggist. He re-enlisted on September 23, 1859, at Boston, Massachusetts, and identified himself as a 5′ 7¾” soldier with hazel eyes, dark hair and a dark complexion. He was assigned to the 2nd Artillery’s Company C and was discharged for disability as a corporal on May 20, 1860, at Fort Independence, Massachusetts. At the time of the 1860 census, he lived in the New Utrecht area of Brooklyn.

Palmer continued his service during the Civil War, although the specific dates are unknown. After his initial service with the 2nd U.S. Artillery, he enlisted as a sergeant in the 1st U.S. Veterans but mustered out as a private. He also served as a second lieutenant in Company A of the 10th Veteran Reserve Corps. As per the 1865 New York State census, he lived in Brooklyn and worked as a clerk. The 1867 Brooklyn Directory lists Palmer as “u.s.a.,” perhaps an abbreviation for United States Army. A Royal Arch Mason, his companions were invited to attend his funeral. As per his death certificate, which incorrectly indicates his year of death as 1880, he was married and worked as an officer. His last residence was in Warren Township in Somerset County, New Jersey, where his wife was a farmer. His death was attributed to dropsy.

After his death on August 11, 1879, he was buried in New Utrecht Cemetery from which he was removed and re-interred at Green-Wood on October 3, 1893. Anecdotally, Walter Palmer, Hoyt Palmer’s son born in 1868, was the chief electrician for The New York Times who designed the first iron and wood ball lit with one hundred 25-watt bulbs and weighing 700 pounds that was used for the first time at the New Year’s Eve celebration in 1907, creating an annual tradition; although one second late, the ball drop attracted a large crowd of men in silk hats and ladies in fur coats. Section13, lot 19694, grave 431.

PALMER, JAMES M. (1843-1929). Private, 44th Massachusetts Infantry, Company I. Palmer was born in Maine. The 1850 census indicates that he lived in Fayette in Kennebuc County, Maine; the 1860 census lists him living with his parents and siblings in Milo in Piscataquis County, Maine. A resident of Weston, Massachusetts, and a farmer by occupation, Palmer enlisted on August 28, 1862, mustered into the 44th Massachusetts on September 12, and mustered out on June 18, 1863, at Readville, Massachusetts. As per his Draft Registration of 1863, he indicated that he had served with the 44th Massachusetts for nine months, lived in Weston and worked as a laborer. He became associated with the Freemasons in Milo, Maine, in 1866, and subsequently affiliated with other lodges when he moved. As per the 1870 and 1880 censuses, he lived in Milo, Maine, was married with children, and worked as a carpenter.

The 1888 and 1890 Brooklyn Directories indicate that he lived at 387 3rd Street and worked as a carpenter; the 1900 census lists him as a builder. In 1904, his application for a pension was granted, certificate 1,103,367. As per the 1905 New York State census, Palmer was living in Brooklyn with his wife and children and was a house builder. At the time of the 1910 census, he lived in Brooklyn, was married, and worked as a ship joiner at the Brooklyn Navy Yard; his wife died in 1914. As per an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on September 26, 1915, Palmer was among 500 Brooklyn veterans who planned to participate in a major G.A.R. event in Washington, D.C., the Grand Review, marking the 50th anniversary of the return of troops from the Civil War. The Ulysses S. Grant Post #327, of which Palmer was a member and a delegate to that event, was selected as an escort to the commander-in-chief of the G.A.R. Many veterans were accompanied by their wives and daughters; members of the Women’s Relief Corps and other auxiliaries also participated in the event. The veterans headed for the nation’s capitol via the Central Railroad of New Jersey. The event also celebrated the forty-ninth anniversary of the founding of the G.A.R. In addition to his G.A.R. membership, Palmer was a member of the Knights of Pythias. The 1920 census reports that he was living with his daughter and son-in-law, Frank Walford, in Brooklyn and was not employed.

Palmer wintered in Florida where he was a director of the Fruitland Park Water Company. An article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 22, 1922, reported that the Women’s Auxiliary of the Grant Post held their annual banquet which was attended by 300 guests and focused on the theme, “Teach Ten Commandments.” Palmer was unable to attend but sent a large box of oranges from Florida where he was spending time with his son. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which confirms his Civil War service, his funeral took place at 258 13th Street, the home of his daughter and son-in-law, George Sahl; members of his G.A.R. post were requested to attend his funeral in full uniform where the ritual of the Grand Army would be observed. He died at his winter home in Fruitland Park, Florida. His death was attributed to a cardiac condition. The Piscataquis Observer of Dover, Maine, was asked to print his obituary. One of Palmer’s sons, the only heir who lived in Fruitland Park, became the executor of James Palmer’s will; he left personal property in Lake County, Florida. Section 188, lot 34096.

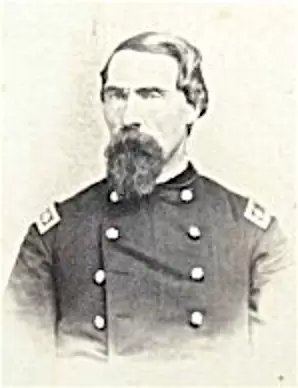

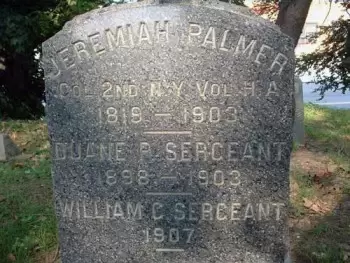

PALMER, JEREMIAH (1819-1903). Colonel, 2nd New York Heavy Artillery. Palmer was born in Herkimer, New York, a village near Utica. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was a contractor who constructed many miles of the New York Central Railroad (completed in 1853) and helped expand the Erie Canal. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a colonel on September 12, 1861, at Utica, New York, and was commissioned into the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery, a unit that he organized, on October 17. An article about the organization of that regiment appeared in the New York Tribune on October 19, 1861, and it was referred to as Palmer’s Battery of Artillery. According to his muster roll, he was a merchant who was 6′ tall with grey eyes, brown hair and a light complexion.

Palmer’s military record was marked by two blemishes. On August 2, 1862, he was dismissed from service for “trying to create a bad feeling amongst the enlisted men against his commanding officer.” Apparently after returning to duty, he was then dismissed again on February 21, 1863, for incompetence because of an unsatisfactory report from the Board of Examination. He soon rejoined the unit as lieutenant colonel and was commissioned in on March 14, 1862. Palmer led the 2nd at the assault on Petersburg, Virginia, where he was wounded in the left shoulder on June 19, 1864; the Brooklyn Daily Eagle incorrectly notes that he was injured at the Battle of the Wilderness. After that injury, in which the bullet came close to his heart and exited his body under his shoulder blade, he was too weak to resume command of his regiment. He was discharged from service on December 7, 1864.

A builder and contractor in civilian life, Palmer lived in Brooklyn for more than thirty-five years. Active in the Republican Party, he was the water registrar in Brooklyn. Among the buildings that he constructed were the Puritan Church at Lafayette and Marcy Avenues and a row of twelve houses on DeKalb Avenue in Brooklyn. The 1870 census listed him as a carpenter. In 1879, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 193,415. As per the 1880 census, he was married, lived at 831½DeKalb Avenue and was a builder. The 1884 Brooklyn Directory lists him as a builder. The Veterans Schedule of 1890 confirms his Civil War service. Melissa Palmer, Jeremiah’s wife, died in 1898, and was buried in Mohawk Cemetery in Herkimer, New York. The 1900 census shows that Palmer was living as a boarder at 831½ DeKalb Avenue, a house that he built, and was working as a carpenter.

An article in the New York Sun in 1902 reported that Palmer, an old veteran of two wars, was a complainant in police court on Gates Avenue seeking the return of jewels that he had given to a young widow, Mamie Murphy, who was 25 years old. Apparently, when the widow’s husband was sick, she and her husband, family friends, lived with Palmer. She needed jewelry to attend a ball and Palmer provided her with several hundred dollars worth of gems. After her husband died, Palmer asked her to marry him but she refused. The magistrate ordered her to give up the jewels, citing that “she should be ashamed of herself”; Palmer was still forlorn that she had rejected his advances.

The circumstances of Palmer’s death are controversial. A widower who boarded with a family at one of his houses at 831½ DeKalb Avenue, he was found dead in his armchair. Although some attributed his death to heart disease, there were gas fumes in the room suggesting that he died from asphyxiation. As per an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 19, 1903, the coroner was called in to investigate his death; suicide was ruled out because Palmer was planning a trip. That article noted that Palmer was survived by a sister who was likely to inherit a large estate. As per an article in the Waterville Times, Mrs. John Carr of Herkimer, whose husband was a bootblack, inherited one-fourth the share of the $100,000 Palmer’s estate (an estate equivalent to $2.7 million in 2018); the Palmers had no children, enumerated nieces and nephews were the other heirs. Section 86, lot 31217, grave 130.

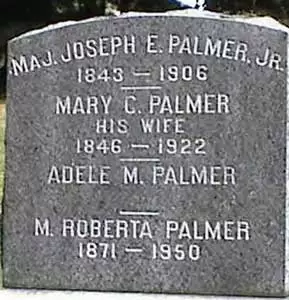

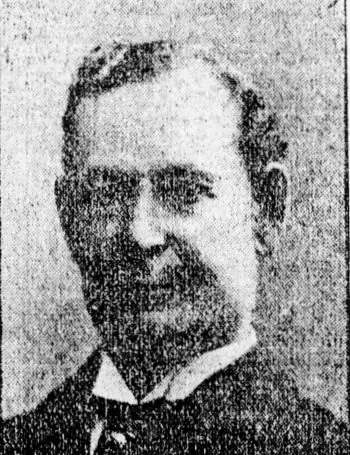

PALMER, JR., JOSEPH E. (1843-1906). Major and captain by brevet; adjutant, 158th New York Infantry, Companies G and C. Palmer was born in New York City. After enlisting at Brooklyn on August 20, 1862, as a sergeant, he mustered into Company G of the 158th New York eight days later. As per his muster roll, Palmer was 5′ 7″ tall with grey eyes, dark hair and a dark complexion. During his service, he rose to sergeant major on December 11, 1862, to second lieutenant on June 6, 1863, effective upon his transfer to Company C, to first lieutenant on September 1, 1863 (with rank from January 5, 1863), and to adjutant on October 31, 1864 (with rank from January 22, 1864). Upon achieving the rank of adjutant he was transferred that day to the regiment’s Field and Staff. An article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1864 noted that while hospitalized at Bermuda Hundred, Palmer learned that his regiment was engaged at the front and thereupon left the hospital to rejoin his regiment. He was brevetted major of United States Volunteers dating from April 9, 1865, “for gallant and meritorious services during the War,” and brevetted captain “for gallant and meritorious services during the campaign of April 1865, against the army of General Lee.” On June 30, 1865, he mustered out at Richmond, Virginia.

As per the New York State census of 1865, Palmer lived with his parents and siblings in Brooklyn and was a bookkeeper for the Army. The 1870 census notes that he lived in Brooklyn with his wife and one-year-old daughter and was a clerk for the Water Board. At the time of the 1875 New York State census, he lived in Brooklyn with his wife, two daughters and a servant and was listed as an oil painter and artist. He was listed as an artist living at 363½ Van Buren Street in the 1877 Brooklyn Directory. Palmer was active in Democratic politics, and was secretary to James Jourdan (see), under whom he had served in the 158th, when Jourdan was president of the Kings County Elevated Railroad Company. On October 28, 1879, the Utica Morning Herald and Daily Gazette reported that Palmer, a former clerk in the Department of the Brooklyn City Works, alleged that William Fowler, while president of the water commissioners, illegally expended $800,000; Fowler denied the accusation and called the charges “old and exploded.” According to the 1880 census, Palmer was listed as a landscape painter who lived in Brooklyn with his wife and children.

Remaining active in military affairs, Palmer served as the national commander of the Union Veteran Legion, a group formed in 1884. That organization was comprised of veterans who had volunteered prior to July 1, 1863, for a term of three years, had served at least two years if discharged for wounds on the battlefield, and were honorably discharged; because of those stiff requirements, the organization was much smaller than the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). An article in the Washington, D.C., newspaper, the Evening Star of August 25, 1892, discussed the planning of a suitable reception for National Commander Palmer, during Grand Army week when Palmer would be headquartered at the Riggs House in the nation’s capitol. Palmer was involved in an unfortunate incident at the Union Veteran Legion Encampment at Indianapolis in the fall of 1892. Apparently, Palmer was in favor of the rejection of the credentials of two of the delegates. Subsequently, another officer, Corporal James Tanner, who lost both of his legs at Second Bull Run, came to the defense of the two men and later confronted Palmer as being a party to the conspiracy to oust the two; Palmer and Tanner nearly came to fisticuffs. Allegedly, the disorder led to a split between the G.A.R. and the Union Veteran Legion. A Pittsburgh newspaper commended Palmer as being “the brainiest” man to lead the organization and work for its good; apparently, others in leadership positions quarreled with past commanders. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on January 7, 1894, that Palmer was awarded a badge by the Union Veteran Legion in recognition of his service to that organization and to the Union for his Civil War service. The badge was made of gold, suspended from a red, white and blue ribbon with a bar inscribed in blue enamel with the name of the organization and a rank bar with three stars, denoting the rank of lieutenant general. That article notes that he was a major on the staff of the 1st Division at the surrender at Appomattox and that President Andrew Johnson later signed his commission as a life major. Further, Palmer was noted as the only Democrat who ever commanded the legion and was a candidate for the post of naval officer of New York.

The 1892 New York State census lists him as retired. He continued with his artwork and was listed as an artist on both the census of 1900 and the 1904 Brooklyn Directory; at that time, he lived at 82 Kingston Avenue. His application for an invalid pension was granted in 1903, certificate 1,059,225. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle confirms his Civil War service and his leadership role in the Union Veteran Legion. His last residence was 82 Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn. His death was attributed to nephritis. Mary Palmer, who is interred with him, applied for and was granted a widow’s pension in 1906, certificate 619,223. As per Mary Palmer’s petition in Kings County Surrogate’s Court, he left an estate valued at less than $50. Section 41, lot 2975.

PALMER, LOWELL M. (1845-1915). First lieutenant, 1st Ohio Light Artillery, Companies C and D; private, 19th Ohio Infantry, Company F. A native of Chester, Ohio, Palmer enlisted as a private on April 24, 1861, mustered into the 19th Ohio three days later, and mustered out on August 30, 1861, at Columbus, Ohio. On October 8, 1861, he re-enlisted as a sergeant and immediately mustered into Battery C of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery. On November 23, 1863, he rose to second lieutenant and was commissioned into Battery D of the regiment. Two months after he was promoted to first lieutenant of his company on October 20, 1864, he mustered out of service on December 29.

His obituary in The New York Times, which confirms his Civil War service, notes that Palmer relocated to Brooklyn in 1866, where he became an important figure in business, philanthropy and the arts. In 1870, he established a terminal for the Erie Railroad called Palmer’s Dock in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. Palmer, a maker of casks and barrels, developed the dock to ship commodities directly to the area and by-pass the congested waterways in Manhattan; the dock closed in 1983. He was the head of the Brooklyn Cooperage Company, an enterprise which made the barrels for the American Sugar Refining Company of which he was a director as of 1899. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which confirms his Civil War service as a teenager, Palmer brought the first railroad to Brooklyn in 1874, and built the first elevated coal pockets there. His interest extended to the arts and was a founder and director of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. In addition, he was president of E. R. Squibb & Sons, the pharmaceutical concern, and vice president of the Palmer Lime and Cement Company. He served as director of trustees to the Franklin Trust Company of Brooklyn, the Manhattan Life Insurance Company of Manhattan, the United States Lloyds Ship Insurance Company, the Market and Fulton National Bank of Manhattan, the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, the Colonial Safe Deposit Company, Colonial Trust Company, New Jersey and New York Zinc Company, and the Union Ferry Company. His application for a pension in 1909 was granted, certificate 1,158,833.

As per his obituary in the New York Herald, he was a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; companions were invited to attend his funeral. Palmer was also a member of the Society of Colonial Wars, the Ohio Society in New York, and was a trustee of the First Presbyterian Church on Henry Street. His last residence was 206 Clinton Avenue in Brooklyn, where he housed a fine art collection and notable private library. Palmer died at his country home, Edgewood, in Stamford, Connecticut. His death was attributed to heart disease. In 1915, Grace Palmer applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 804,650. An article in The New York Times on July 6, 1919, reported that Palmer’s estate was valued at $2,334,311 (about 50 million today). Section 125, lot 26169.

PALMER, NATHANIAL (or NATHANIEL) WILLIAM (1848-1915). Musician, 120th New York Infantry, Company E. Born in England, Palmer immigrated to the United States in 1853. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a private on August 22, 1862, at Kingston, New York, mustered immediately into the 120th New York, and was promoted to musician on December 31, 1863. His muster roll notes that he was detailed as a nurse at Corps Hospital in the summer of 1864 and at the Field Hospital in April 1865. Palmer mustered out with his company on June 3, 1865, at Alexandria, Virginia.

On October 19, 1880, Palmer became a naturalized citizen. The 1882, 1884, and 1886 Brooklyn Directories list him as a driver. In 1887, his application for an invalid pension was granted, certificate 1,092,814. As per the Brooklyn Directory for 1889 and 1890, he was still working as a driver. Remaining active in military affairs, he held leadership positions in the Moses F. Odell Post #443 of the G.A.R., including officer of the guard in 1890 and junior vice commander in 1902. The Veterans Schedule for 1890 confirms his Civil War service. The 1900 census shows that he lived in Brooklyn with his wife and children and was still employed as a driver. The 1904 Brooklyn Directory and the 1905 New York State census report that he was a clerk. As per the 1910 census, he was a watchman for the railroad. Palmer’s obituaries in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and The New York Times, which confirm his Civil War service, indicate that he had been a Brooklyn resident for forty-five years and worked as a foreman for the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company at its sand pit at Rockaway Avenue and Beasley Lane. As per his death certificate, he was a widower who worked as a watchman. He last resided at 394 Rugby Road in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to heart failure. Section 202, lot 32541, grave 4.

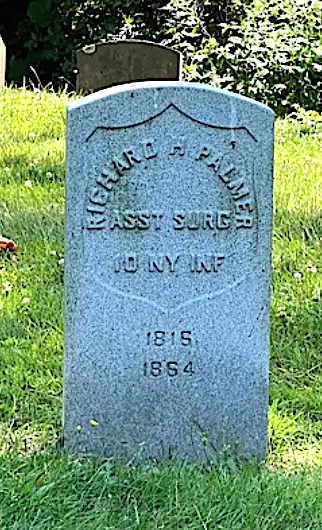

PALMER, RICHARD HENRY (1816-1864). Assistant surgeon, 10th New York Infantry; hospital steward, 170th New York Infantry, Company H. Palmer was born in Ireland. On April 5, 1846, he married Harriet Leslie at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Brooklyn. As per the 1855 New York State census, he lived in Brooklyn with his wife, three young children and a servant; he was listed as a doctor. On July 6, 1857, the New York Tribune and the American Phrenological Journal reported that Harriet Palmer, known as Hattie, the couple’s eight-year-old elder daughter, died in a tragic boating accident at Lake Ronkonkoma, New York. John Leslie, the uncle of the little girl, also perished when the boat capsized; five people survived the accident including John Leslie’s 17 year-old daughter and John W. Palmer, little Hattie’s brother. A lengthy article on the tragedy in the New York Herald of July 9, 1857, noted that the boaters were celebrating the July 4th holiday and that an experienced captain was not onboard as was usual for the family. According to the census of 1860, Palmer lived in Brooklyn with his wife, two sons and a daughter; he was listed as a physician.

During the Civil War, Palmer enlisted on August 11, 1862, and mustered into the 170th New York as a hospital steward on October 7. He was commissioned as an assistant surgeon on April 7, 1864, with rank from March 24, and transferred on April 30, 1864, at Stevensburg, Virginia, into the Field and Staff of the 10th New York. As per his muster roll, he was absent in October 1864. He died of disease at Brooklyn on December 4, 1864, while on furlough. On March 16, 1865, Harriet Palmer applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 74,632; at the time of her application, she lived in St. Claire, Missouri, and had two children under the age of 16. After Harriet Palmer died in 1867, John W. Palmer, guardian and elder son, applied for and received a pension for a minor, his younger brother, St. Leger Palmer, on February 2, 1869, certificate 132,194; his sister, Agnes, had reached the age of majority by that time. Section 42, lot 805.

PALMER, WILLIAM (1831-1904). First lieutenant, 82nd New York Infantry, Companies B, E, and F; 15th Veteran Reserve Corps, Company D. Of Irish birth, Palmer enlisted as a private at New York City on April 17, 1861, and mustered into Company B of the 82nd New York on May 21. He became a first sergeant of Company B and then on April 30, 1862, was commissioned as a second lieutenant, effective upon his transfer to Company E on June 24. Palmer’s promotion to first lieutenant on June 20 became effective upon his transfer to Company F on December 27, 1862. He was severely wounded in the left ankle at Cemetery Ridge at the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 2, 1863, necessitating the amputation of that limb. He was transferred to the 15th Veteran Reserve Corps on June 24, 1864, from which he was discharged on June 30, 1866. His application for an invalid pension was granted on October 22, 1866, certificate 80,927.

Palmer was a member of the G.A.R.’s James C. Rice Post #29 in New York City as of June 18, 1881. A businessman in plumbing and steam-fitting in New York City, he was active in civic organizations such as the Odd Fellows and the Guiding Star Lodge. His military service was noted in his obituary in The New York Times. He died at the home of his niece in Fishkill, New York. His death was attributed to heart failure. His wife applied for and received a widow’s pension shortly after his death, certificate 591,452. Section 174, lot 18375, grave 5.

PALMO, LEOPOLD (1828-1873). Private, New York Union Coast Guard, Company G; 99th New York Infantry, Company C. Originally from Naples, Italy, Palmo was hospitalized for one day at the Charity Hospital in New York City in November 1851 for ptyalism (excessive saliva); he was listed as a barkeeper on his admission data. During the Civil War, Palmo enlisted as a private on May 28, 1861. On June 14, 1861, he mustered into Company G of the New York Union Coast Guard and transferred into the 99th New York on September 1, 1861, as a private. As per his muster roll, Palmo often served as a cook in the Regimental Hospital and was hospitalized at the General Hospital in Fort Monroe, Virginia, in September 1863. He mustered out on July 2, 1864, at New York City. As per his death certificate, he was single and worked as a trader. His last residence was 50 Centre Street in Manhattan. His death was attributed to “debility.” Section 114, lot 8999, grave 728.

PANGBORN, RICHARD E. (1844-1876). Private, 1st New York Sharpshooters, 9th Company. A Brooklynite by birth, Pangborn enlisted as a private at Lebanon, New York, on October 7, 1862, mustered into the 1st Sharpshooters on January 22, 1863, and mustered out on August 5, 1863, at Albany, New York. According to the 1870 census, he was a clerk in a paint factory living in Brooklyn, owned real estate valued at $16,000, and personal property worth $2,000. His last residence was 32 Braxton Street in Brooklyn, where he succumbed to diarrhea. Section 115, lot 20864.

PANIER, FREDERICK ALEXIS (1840-1913). Corporal, 17th New York Infantry, Company D. A native of Paris, France, Panier immigrated to the United States from Hamburg, Germany, aboard the Humboldt on July 16, 1860, and arrived in New York City. As per the passenger manifest, he was a barber. During the Civil War, he enlisted at New York City as a private on May 20, 1861, and mustered into Company D of the 17th New York that same day. His soldier record, which is filed as Frederick Parrier, notes that he was taken as a prisoner of war at the Battle of Second Bull Run on August 29, 1862. As per his muster roll, he was present on October 21, 1862. He was promoted to corporal on January 27, 1863, detached to the Provost Guard until April 1863, and mustered out at with his company at New York City on June 2, 1863.

On October 28, 1864, he became a naturalized citizen; that document uses the spelling “Paniery.” The New York State census of 1865 reports that he lived in Brooklyn and worked as a barber. He is also listed as a barber at 71 Court Street in the 1868 Brooklyn Directory. Articles in the Evening Telegram and Brooklyn Daily Eagle of October 27, 1869, note that Panier’s apartment was burglarized after the thieves scaled a fence and gained entry through a rear window; $68.00 worth of jewelry was taken. Panier’s obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which confirms his Civil War service, notes that he became a costume designer after the Civil War, first on Atlantic Avenue and then on Fulton Street in Brooklyn. The 1875 New York State census lists him as living in Brooklyn with his wife and two children and mother-in-law; he was working as a costumer at that time. Panier is listed as a costumer in the Brooklyn Directories for 1877, 1881, 1888 and 1889 and on the 1892 New York State census. He was the costumer for the Emma Abbott Opera Company at the Park Theater. He then designed costumes and directed carnival tableaux for the Brooklyn Saengerbund, a singing club of which he was an honorary member for forty years, and other German societies. He also directed, costumed and acted in productions of the Ulk Dramatic Club.

The 1890 Veterans Schedule confirms Panier’s Civil War service. In 1897, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 962,651. The 1900 census and the 1910 census report that he lived in Brooklyn with his wife and owned a costume shop. His death certificate indicates that he was a costumer and was married. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Veterans of the 17th Regiment, the Brooklyn Saengerbund and the Ulk Dramatic Club were invited to attend his funeral. His last residence was 55 Ashland Place in Brooklyn; Panier had lived in Brooklyn for fifty-two years. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that his death was attributed to “brain trouble”; the New York Herald, which also confirms his Civil War service, notes that he died from general debility. Shortly after his death in 1913, his wife, Oldina (Ottilie, Delia) Panier, who is interred with him, was granted a widow’s pension, certificate 765,866. Section 16, lot 14888, grave 83.

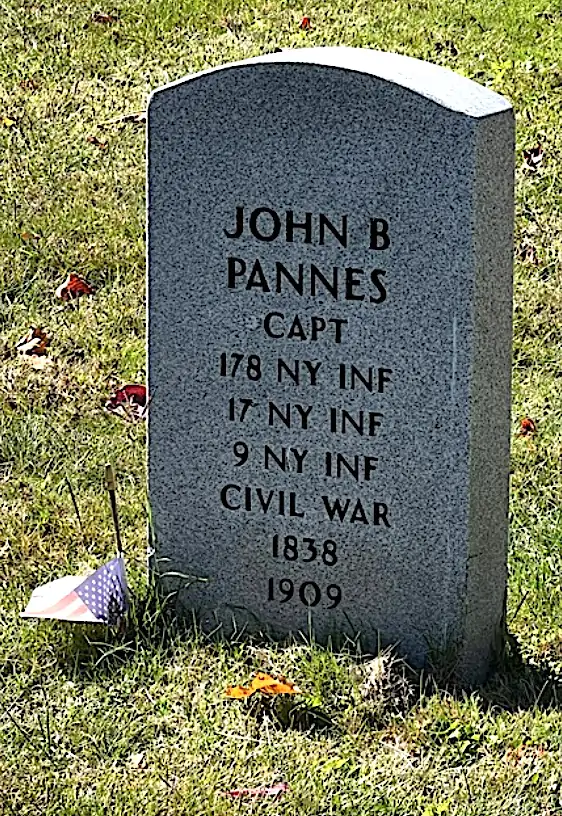

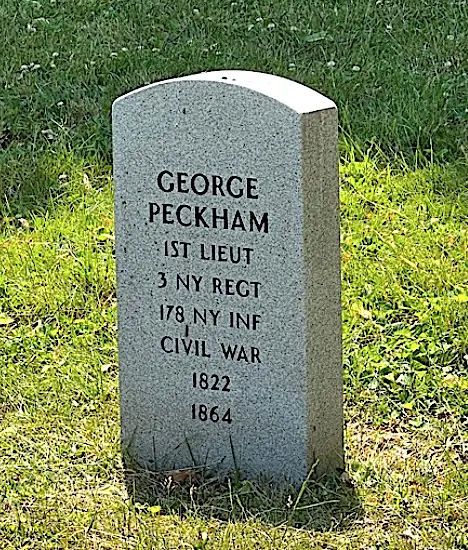

PANNES, JOHN B. (1837-1909). Captain and aide-de-camp, United States Volunteers; captain, 178th New York Infantry; ordnance officer, 17th New York Veteran Infantry, Company I; first lieutenant and adjutant, 9th New York Infantry, Company A. Born in Cologne, Germany, Pannes immigrated to the United States when he was nineteen years old. He filed papers for naturalization on September 6, 1859. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a private at New York City on April 23, 1861, and mustered into Company A of the 9th New York, known familiarly as Hawkins’ Zouaves, on May 4. He was promoted to sergeant on October 14, 861, and to quartermaster sergeant on March 20, 1862, at which time he transferred into the Field and Staff. On May 20, 1863, he mustered out at New York City. Pannes re-enlisted as first lieutenant on June 5, 1863, at New York City, and was commissioned into the Field and Staff of the 9th New York four days later. He was promoted to first lieutenant and adjutant upon his enlistment. On October 14, 1863, he mustered out at New York City when his regiment was consolidated with the 17th New York Veteran Infantry. As per The History of the 9th Regiment by Lieutenant Matthew J. Graham, Pannes was slightly wounded in the neck at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, where he was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Edgar A. Kimball (see), and was one of the men who became an officer when the regiment was consolidated. He was commissioned into Company I of the 17th on December 30, 1863, the same day as his promotion to second lieutenant.

On January 15, 1864, Pannes achieved the rank of acting ordnance officer of the 16th Army Corps in the Mississippi. Major General A. J. Smith, in his report to headquarters describing the operations in Red River, Louisiana, in 1864, commended Pannes for his untiring efforts, and wrote of his staff, “Arms, eyes, and heads seemed their main attributes during the whole campaign.” Subsequently, he served as a captain in the 178th New York, effective after he was commissioned into that regiment on March 14, 1865. He was appointed captain and aide-de-camp of United States Volunteers on March 23, 1865, relieved of military responsibilities on September 4, 1865, as per Special Order no. 43, Extract 14, and mustered out October 12, 1865.

After returning to New York City, Pannes studied law and was admitted to the bar on December 16, 1868. According to his obituary in The New York Times, which confirms his Civil War service, Pannes was a law partner of his former commander, General Rush C. Hawkins, and another comrade, George A. C. Burnett, from the end of the Civil War until 1907, in the firm Hawkins, Barnett & Pannes; subsequently, he was a senior partner at the law firm of Pannes & Blau. The 1870 census indicates that he was a lawyer living in New York City in the household of Caroline Clark. The New York Times reported on February 28, 1877, that Pannes was elected president and treasurer of the New York Dispensary.

Active in German organizations, he was a founding member of the Arion Society, a German-American musical organization, and was twice its president. The New York Times reported on December 21, 1894, that Pannes was elected an officer of the German-American Reform Union, an organization that hoped to become a political party, in the primary held in the Nineteenth Assembly District. Further, it was reported that Pannes, in his role as president of the German-American Citizens Union, addressed the New York State Senate Committee on Taxation and Retrenchment and the Assembly Committee on Excise; he noted that reform was not exclusive to any class or sect of the citizenry. The New York Herald reported on February 28, 1896, that Pannes, representing the German-American Citizens Union, went to Albany with Carl Schurz and other notables of German heritage, bearing a petition with 115,000 signatures asking that New Yorkers be permitted to vote on the sale of beer and other spirits on Sundays between the hours of 1:00 and 10:00 p.m. An article in the New York Tribune on October 1897 noted that Pannes was elected president of the Bürgerbund Executive Committee. In that article, it was noted that the group cooperated with the workers in the Citizens Union, which shared the building, and that although the German members of the Citizens Union were not all Republicans, they favored municipal reform and supported the candidacy of Seth Low. In addition, the German-American Citizens Union believed that Low would support their position on the liquor laws.

On April 19, 1890, when Pannes was president of the Hawkins’ Zouaves, he extended an invitation of “Peace and Good Will” to the 3rd Georgia Volunteers for a reunion with their former foes. As per his passport application of April 30, 1900, for a sailing to Antwerp, Belgium, he was a lawyer who was 6′ tall with a high forehead, light brown eyes, a long nose, grey hair, fair complexion, full face and broad chin. In 1891, Pannes was president of the Liederkranz of New York, a male singing society. In 1900, he was living with the Clark family on Park Avenue in New York City. In 1905, his application for a pension was approved, certificate 1,104,059. According to his death certificate, he was single, a lawyer and was interred at Fresh Pond, Long Island, on March 10, 1909; his Green-Wood burial date is listed as April 24, 1909. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, members of the Hawkins Zouave Association (9th New York) were invited to attend his funeral. He last lived on East 92nd Street in Manhattan. His funeral took place at the Arion Society’s clubhouse on Park Avenue and East 39th Street. Section F, lot 18530.

PARDEE, CHARLES INSLEE (1837-1899). Assistant surgeon, 16th New York Infantry; 4th New York Brigade State Militia. Pardee was born in Romulus, New York, in Seneca County. His ancestry can be traced to William Brewster of the Mayflower settlers. Pardee was a graduate of the Medical Department of the University of the City of New York, class of 1860. During the Civil War, he enlisted on August 30, 1862, at New York City, and was commissioned into the Field and Staff of the 16th New York on September 13, 1862. According to his muster roll, which indicates an incorrect birthplace of New York City, Pardee was a physician who was 5′ 5″ tall with blue eyes, brown hair and a dark complexion. As per his obituary in the resolutions of condolence of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion, a patriotic organization comprised of Civil War officers, and of which he was a member, he was assigned to the hospital at Frederick, Maryland, after the Battle of Antietam. He then was at the front with the 16th at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862, participated in the historic mud march of Burnside’s army, and in the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia. He mustered out on May 22, 1863, at Albany, New York. Subsequently, he served in the Field and Staff of the 4th Brigade, New York State Militia, in 1863.

Pardee returned to his medical practice, serving as an assistant surgeon at the Manhattan Eye and Ear Hospital beginning in 1866 and becoming its director in 1875. He is listed as a physician living in Manhattan in the census of 1870 and in the 1874 and 1877 New York City Directories. Among his other medical affiliations included his service as a contract surgeon to the New York City Asylum for the Insane, lecturer on Diseases of the Eye and Ear at the University of the City of New York, secretary of the Alumni Club at the aforementioned institution from 1870-1876, president of that organization from 1876-1877, professor of otology (anatomy and diseases of the ear) at the University of the City of New York, 1874-1897, and dean of the University Medical College from 1878 through 1897. In 1879, he was a founding member of the American Medico-Psychological Association because of his connection to the Manhattan State Hospital, and served as its secretary throughout his lifetime. On May 15, 1897, The New York Times reported that the New York University Medical College was formed by merging the Bellevue and the University Schools. When the staff was reorganized, Pardee was named professor emeritus of otology. In addition, he was a member of the New York Academy of Medicine and other medical societies.

Proud of his colonial roots, he was a life member of the New England Society. He also was a life member of the Lotos Club, of which he was a vice-president, the Union League and fleet surgeon of the American Yacht Club. His death certificate notes that he was married and a doctor; it also notes that he was cremated at Fresh Pond. In its tribute of condolence, the Loyal Legion noted that Pardee considered his interest in that organization “a valued inheritance of the war, and to wear the button a great distinction.” The Farmer’s Review of Seneca, New York, posted the notice of his death and his birthplace in Romulus. He last lived at 6 East 43rd Street in Manhattan. His death was attributed to apoplexy. Section 101, lot 4734, graves 9 and 10.