MORROW, THOMAS (1837-1881). Private, 84th New York (14th Brooklyn) Infantry, Company A. Originally from Ireland, Morrow enlisted at Brooklyn as a private on April 18, 1861. He mustered into the 14th Brooklyn on May 23, 1861, and deserted from an Army Field Hospital, place unknown, on March 1, 1863. His last residence was 152 Forsyth Street in Manhattan. He died from Bright’s disease. Section 121, lot 7639, grave 132.

Civil War Bio Search

MORSE, CHARLES (1840-1886). Private, 9th New York Infantry, Company A. Morse was a native of Bradford, New Hampshire. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a private at New York City on May 6, 1861, mustered into Company A of the 9th New York that same day, and mustered out on May 20, 1863. (His admission papers at the Togus Soldiers’ Home list May 2, 1861, through May 25, 1863, as his service dates.)

After the Civil War, he lived in St. Joseph, Missouri. On June 10, 1885, he was admitted to the Soldiers’ Home in Togus, Maine, suffering from intermittent fever. His admission record notes that he had $255 in personal effects which were sold. He died six months later from tuberculosis at the hospital associated with the Soldiers’ Home. His mother, Caroline Morse, who is interred with him and who died in 1881, left these instructions for her burial and for the burial of Charles, who was unmarried, in her last will and testament:

…First, I direct that my body shall be decently interred by the side of my late husband in my quarter lot No. 22092 in Greenwood (sic) Cemetery and that a headstone be erected over my grave of the same size and design as that now over my said husband’s grave. Second, I direct that in case I survive my son hereinafter name that he shall also be decently buried in said lot and have a headstone erected over his grave of a similar size and design to that above mentioned and the bodies of my said husband, myself and said son be buried side by side and, that no other bodies be interred in said lot….

Section 147, lot 22092.

MORSE, JAMES EDWARD (or EDWARDS) FINLEY (1825-1914). Private, 51st New York Infantry, Company H. James Edward Finley Morse was a son of Samuel F. B. Morse (see), the famed inventor of the telegraph and artist, and they are buried in the same lot. His birth place is unclear: although the 1860 census says Connecticut, where he was baptized, an obituary indicates South Carolina as his birthplace and his records from the Home for Incurables notes New York as his place of birth. During the 1820s, his family relocated to New York City. As per the census of 1860, he was labeled “idiot,” a term that most likely means mentally challenged.

Despite any disability, Morse enlisted as a private at New York City on July 31, 1861, mustered into the 51st New York three days later, and was discharged at Annapolis, Maryland, on December 20, 1861. In April 1910, he entered the Home for Incurables in the Bronx where he resided until his death. The cause of his death was nephritis. The Home for Incurables, now known as St. Barnabas Hospital, was founded in 1866 as a haven to bring hope and medical care to those who had neither. Dr. P. C. Pease, the Home’s first physician, said in 1867, “…where the faintest hope exists, no efforts are spared nor are any new remedies left untried….” Section 25, lot 5761.

MORSE, JOSEPH W. (1812-1895). Unknown soldier history. Originally from Massachusetts, the details of Morse’s service are not known. He was a member of the G.A.R., an association for veterans of the Civil War. He last lived at 268 West 12th Street in Manhattan. His death was attributed to “age.” Section 192, lot 23649, grave 2.

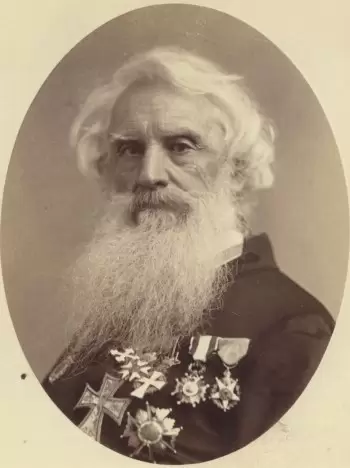

MORSE, SAMUEL FINLEY BREESE (1791-1872). Painter, photography pioneer, and inventor of the telegraph. Born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, he graduated from Yale College in 1810 with honors as a Phi Beta Kappa. The next year he went to England to study painting with expatriate Americans Washington Allston and Benjamin West. Returning to the United States, he developed a reputation as one of the best portrait artists of his era and was also well-known for his panoramic interiors such as The House of Representatives (1821-22) and The Gallery of the Louvre (1831-1832). Though he had only limited commercial success as a painter, he was one of the leading painters of the romantic school in the United States and was perhaps its leading portraitist. He was elected the first president of the National Academy of Design in 1826 and served in that position until 1845, then 1861-1862. Under his leadership, the National Academy, run by artists, established lectures, a course of study, and annual exhibitions to train American painters and sculptors and to promote their work.

Morse was also known for his political views. Under the pen name “Brutus” he wrote a series of anti-Catholic articles in the early 1830s, which made him the founding father of Nativism. He ran as the unsuccessful anti-immigration candidate (ironically, it was his father, Jedidiah Morse, who coined the phrase “immigrant,” to replace the more traditional “emigrants,” to emphasize that new Americans were entering a new land, rather than leaving their old country) for New York City mayor in 1836. During the 1850s, Morse supported slavery, considering it to be sanctioned by God and was strongly opposed to the abolitionists of which he said, “…a more wretched, disgusting, hypocritical crew, have not appeared on the face of the earth since the times of Robespierre.”

Morse’s other interests, which ultimately brought him world renown, were in the sciences and technology. As the 1830s progressed he painted less and less as he turned his attention to experiments with electricity. He applied for a patent for his revolutionary telegraph in 1837, introduced photography (which he learned from France’s Louis Daguerre in March of 1839) to the United States in 1839, took the first daguerreotype group portrait in 1840 (capturing the image of the reunion of the Yale Class of 1810), trained several of America’s first photographers (including Mathew Brady and Edward Anthony) (see), created the Morse Code, established the first underwater telegraph, and sent his famous message “What hath God wrought” from Washington to Baltimore on May 24, 1844. The telegraph, together with the rapid expansion of newspapers after the invention of the rotary press, revolutionized communication and provided the public with access to news happening hundreds of miles away.

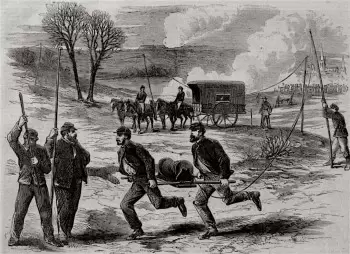

Although first used during the Mexican-American War, 1846-1848, the telegraph was transformative during the Civil War. President Lincoln, realizing the value of this new technology, was a fixture in the War Department building, adjacent to the White House. He waited for the messages from the battlefield each day and learned the latest news from the front from his telegraphers, one of whom, Charles A. Tinker (see), is buried at Green-Wood. The telegraph enabled President Lincoln to have “eyes and ears” on the battlefield and to communicate rapidly with his generals. Telegraph systems, constructed portably with wires and poles, were set up by men, horses, and wagons. (See photo below.) Most cipher operators worked from wagons although some were in buildings. Telegraph operators had a dangerous job and more than 300 suffered casualties during the Civil War from disease, injury, battlefield death, or capture. Because there was an additional danger that the messages could be read by the enemy, new, secret codes were repeatedly invented and used.

Although he was one of the organizers of the American Society for Promoting National Unity in early 1861, Morse was an active Peace Democrat critical of Lincoln during the Civil War. He also was a founder of Vassar College (1861). His last public appearance was on January 17, 1872, when he and Horace Greeley (see) unveiled a statue of Benjamin Franklin, which still stands on Park Row in New York City. Though he purchased a lot at Mount Auburn Cemetery in his native Massachusetts, he ultimately chose Green-Wood as his final resting place. One of his sons, James E.F. Morse (see), was with the 51st New York during the Civil War. An article in The New York Times on July 30, 1982, notes that Morse’s painting, The Gallery of the Louvre, was purchased for $3.25 million by Daniel Terra, founder of the Terra Museum of American Art in Evanston, Illinois, for display there and for touring throughout the United States; it was the highest price paid for an American work of art at that time. Section 25, lot 5761.

MORTIMER, RICHARD (1842-1920). Private, 13th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company D. A New York City native, Mortimer enlisted as a private at Brooklyn on May 28, 1862, mustered into the 13th Regiment that same day, and mustered out with his company at Brooklyn on September 12, 1862. In 1902, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 1,068,778. As per the 1910 census, he was single, lived with his brother on Edgecombe Avenue in the Bronx, worked as a bookkeeper, and could read and write. He last lived in the Bronx at 950 East 225th Street. The cause of his death was tuberculosis. Section 161, lot 15607.

MORTIMER, SAMUEL (1812-1890). Fireman second class, United States Navy. Born in England, Mortimer enlisted as a fireman second class in the United States Navy on November 24, 1862, and served aboard the USS Princeton, a receiving ship. The Princeton was stationed at the Navy Yard in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was used by new recruits or for men in transit between stations. He was discharged on December 31, 1863. The Brooklyn Directory for 1878 lists Mortimer as a laborer; the 1889 Brooklyn Directory lists him as a grocer. He last lived at 72 4th Street in Brooklyn. In April 1939, the Honor Legion of the Police Department applied for a government-issued headstone for Mortimer, citing his Civil War service. Section 135/6, lot 28307, grave 490.

MORTON, ELLISON M. (1845-1919). First lieutenant, 6th New York Cavalry, Company B; second lieutenant, 18th New York Cavalry, Company I. After enlisting as a second lieutenant at Fort Columbus, New York, on December 2, 1862, he mustered into the 18th Cavalry that day, and was promoted to second lieutenant on November 25, 1863. He re-enlisted as a first lieutenant at Winchester, Virginia, on February 4, 1865, mustered immediately into the 6th Cavalry, and mustered out at Cloud’s Mills, Virginia, on June 28, 1865. Remaining interested in military affairs, Morton was a member of the G.A.R. Section 6, lot 20118, grave 21.

MOSELEY (or MOSELY, MOSAELEY), JACOB HERRICK (1839-1911). First sergeant, 80th New York Infantry, Company A. Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, Moseley enlisted as a private on September 26, 1861, at Kingston, New York, having served previously in the 20th New York State Militia, and mustered into the 80th New York that same day. The 80th New York, also known as the Ulster Guard, was formed by the reorganization of the 20th New York Militia, one of the oldest militia regiments in New York State. As per his muster roll, he was absent and sick in the hospital in July 1862. Rising through the ranks, he was promoted to corporal and first sergeant before being discharged on September 26, 1864.

In civilian life, Moseley was a dentist in Brooklyn; his dental practice was in his home. In 1898, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 980,237. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Standard Union, which confirms his Civil War service, he lived in Brooklyn for forty-five years and was a member of Ulysses S. Grant Post #327; the Grant Post officiated at burial services with full military honors. One obituary reports that the flag at Grant Post headquarters was flown at half-staff upon news of his death. He last lived at 206 Clermont Avenue in Brooklyn. His widow, Margaret Moseley, received a pension in 1912, certificate 1,739,113. Section 140, lot 24174, grave 2.

MOSHER (or MOSHIER), THEODORE GORDON (1842-1905). Private, 83rd New York Infantry, Company D; 97th New York Infantry, Company D. A native of New York City, Mosher enlisted there as a private on February 25, 1862, and mustered into the 83rd New York that day. On December 13, 1862, he was captured at Fredericksburg, Virginia, and released on an unspecified date. He was transferred into the 97th New York on June 7, 1864, and mustered out at Ball’s Cross Roads, Virginia, on July 18, 1865.

The 1880 census reports that he was living in New York City with his mother and worked as a clerk in the hat business. On April 14, 1884, he mustered into the Abel Smith Post #45 of the G.A.R.; at that time, he was working as a clerk. The 1900 census notes that he was married with a son and working as a clerk. In 1902, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 1,058,899. As per his obituary in The New York Times, members of the Abel Smith Post and members of the 83rd Veterans’ Association were invited to attend his funeral. That obituary also noted that he died “after a lingering illness endured with patient fortitude.” His last address was 369 West 123rd Street, Manhattan. Mosher’s funeral was held at the Sixteenth Baptist Church at West 16th Street and Eighth Avenue in Manhattan. Shortly after his death in 1905, Anna Mosher, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 660,869. Section 57, lot 2158, grave 1.

MOSS, HENRY (1830-1875). Private, 1st New York Infantry, Company H. Born in London, England, he enlisted as a private on March 18, 1862, mustered into the 1st New York that day, and was listed as “missing on the march” on November 13, 1862. His muster roll notes that an investigation into his disappearance failed to elicit further information. The 1872 New York City Directory lists him as living at 459 Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn and working as a broker at 41 South Street in Manhattan. As per his obituary in The New York Times, he was a ship broker at 32 South Street in Manhattan with the firm Moss & Ward for many years. Moss was a member of the Maritime Exchange and was a Freemason; members of his lodge were asked to gather at their Masonic Temple before attending his funeral. His last residence was 415 Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn. The cause of his death was consumption. Section 119, lot 10898.

MOSS, JR., JOHN R. (1819-1887). Principal musician, 9th New York Infantry, Band. Of English origin, Moss enlisted as a private at New York City on August 30, 1861, and mustered into the Band of the 9th New York that same day as a principal musician. On April 19, 1862, he was taken as a prisoner of war at the Battle of Camden, North Carolina, and was discharged by order of the War Department on May 21, 1862, as a paroled prisoner at Washington, D.C.

Moss is listed as a tuner in the 1867 and 1879 New York City Directories; the 1870 census lists him as a pianist. According to the 1880 census, he was working as a piano tuner; his wife, Eliza, a homemaker with six children, was partially paralyzed. His last residence was 205 East 41st Street in Manhattan. He death was caused by apoplexy. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, his funeral was private. In 1890, Eliza Moss applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 364,466. That same year, she confirmed his service in the Civil War for the 1890 Veterans Schedule. Section 15, lot 17263, grave 2000.

MOSSCROP, THOMAS DERBYSHIRE (or DARBYSHIRE, DERBISHIRE) (1839-1912). Major by brevet; captain, 10th New York Infantry, Companies F and K. A native of Manchester, England, he was baptized as Thomas Darbyshire Mosscrop at St. George’s Church in Lancashire. He immigrated to the United States from Liverpool when he was six years old and his family first settled in Hartford, Connecticut, before moving to New York City six years later. His family moved to Brooklyn in 1850.

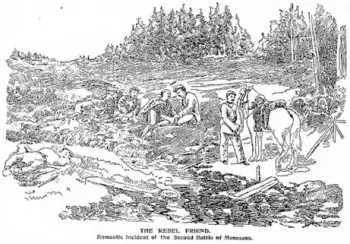

During the Civil War, Mosscrop enlisted as a second lieutenant at New York City on April 26, 1861, and was commissioned into Company F of the 10th New York that day. His appointment to first lieutenant was made on October 4, 1861. After being wounded and left for dead at the Battle of Second Bull Run, Virginia, on August 30, 1862, he was cited for gallantry by his commanding officer, Colonel Gouverneur K. Warren, who led the 5th and 10th New York Regiments there. Warren wrote from headquarters on September 6, “…We assisted from the field 77 wounded of the Fifth and 8 of the Tenth. The remainder fell into the hands of the enemy. Among these was…Lieutenant Mosscrop…of the Tenth. Braver men than those who fought and fell that day could not be found. It was impossible for us to do more, and, as is well known, all the efforts of our army barely checked this advance.”

According to his obituary in The New York Times, Mosscrop was saved at Bull Run by a Confederate officer, Captain Hugh Barr of the 5th Regiment of Virginia Riflemen, who recognized a Masonic pin worn by Mosscrop. This action was confirmed by Daniel N. Rolph in My Brother’s Keeper: Union and Confederate Soldiers’ Acts of Mercy During the Civil War and other sources. According to Rolph, upon discovering that Mosscrop was a Mason and exchanging a few words, Barr summoned a surgeon who dressed his wounds, then took Mosscrop and two soldiers found with him to the Van Pelt house, a makeshift hospital where they remained until their wounds healed. Later, the three soldiers were taken to Washington, D.C., rather than a prison camp, and paroled. Years later, the Union soldiers remembered the Virginia Mason who “regarding a fallen foe as a friend in need, did all in his power to save their lives.” This act of mercy was also recorded by Michael Halleran in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Freemasonry in the American Civil War.

Mosscrop was promoted to captain on October 1, 1862, transferred that day to Company K, and resigned from service on January 1, 1863. His soldier history indicates that he also served at Fort Monroe and Norfolk, Virginia, and was in the Peninsula and Pope’s Campaigns. In 1866, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 117,693. On November 16, 1867, he was brevetted to major “for gallant and meritorious services in the late War.”

The 1870 census and the 1878 Brooklyn Directory note that he worked for U.S. Customs. In 1878, he married Sarah Millon (or Milton), the sister of his first wife, Emma, who had died. The 1880 census and the 1883 Brooklyn Directory record that he lived in Brooklyn and worked as a deputy tax collector. On April 14, 1882, the Wheeling Register [of West Virginia] reported the reunion of the three soldiers with their Confederate savior, “How Three Grateful Union Soldiers of Brooklyn Have Rewarded the Noble Act of a Confederate Soldier on the Battlefield.” That article recounts how Hugh Barr of Moorhead, West Virginia, was feted in Brooklyn on August 30, 1881, by Mosscrop and the two men who were with him at Bull Run when Barr helped assist them on the battlefield after seeing Mosscrop’s Masonic emblem on his shirt. Barr was presented with a picture of the battlefield and an engraved resolution recognizing and remembering his “brotherly love and humanity” and assuring him of “their heartfelt wishes for his future welfare and happiness.” The resolutions and picture were bequeathed to the grand lodge of Masons of Virginia upon Barr’s death.

As per his obituaries in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, The New York Times and the Brooklyn Standard Union, which confirm his Civil War service and note his rescue at Bull Run, Mosscrop was the superintendent of the Office of the Commissioner of Records at the time of his death. Previously, he had been an internal revenue collector, a registrar of arrears, and tax collector in Brooklyn. According to his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was active in Republican Party politics and used his status as a veteran to prevent his removal as superintendent of the Records office when John K. Neal tried to remove him from his position; Mosscrop reiterated that he had had been an efficient public servant and was entitled to remain in his job. An article in the New York Tribune on May 23, 1899, states that Mosscrop was retained as superintendent for the new Commissioner of Records; that article said that George Waldo, the new commissioner, did not want to antagonize Republicans and that Mosscrop was well-suited for the position.

He joined the G.A.R. in May 1882 and was a member of Brooklyn’s Winchester Post #197. An article in the May 16, 1900, edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle notes that Mosscrop weighed in on the Barbara Fritchie controversy as to whether Fritchie (spelled Frietchie in the famous poem) actually waved the Union flag that was taken from her window in Frederick, Maryland. Mosscrop, who cited his friendship with Hugh Barr, the Virginian Mason who saved his life at the Battle of Run, was at Frederick when he saw men take a flag from a woman and were “about to roll it in the gutter and then drag it through the streets.” Barr considered this to be cowardly and said, “The first one who dares to soil this lady’s banner will receive a bullet through his heart,” before returning it to its owner. Mosscrop by citing this story in a letter from Barr dated June 20, 1879, placed himself on the side of those who believed the Barbara Fritchie story to be true and not the poet John Greenleaf Whittier’s fancy.

In addition, Mosscrop was active in Republican Party politics and belonged to the Military Order of the Loyal Legion, Brooklyn Masonic Veterans, Union League and Invincible Club. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on June 6, 1905, that Mosscrop, R.A. Dimick and Edward Dubey (who was in the Color Guard) went to Dugan’s Farm, the site where they were rescued because of their Masonic membership at invitation of the Society of the Army of the Potomac at Manassas (the Confederate name for Bull Run), and placed at plaque at the spot where they were saved by Hugh Barr; Barr had died in the mid 1890s but Dubey still helped support his widow.

In May 1907, Mosscrop’s 29-year-old daughter, Emma, took her life in Montreal, Canada, where she worked for a publisher; an article about her death in the Boston Globe noted that her father said that she had previous mental health problems. The 1910 census reports that Mosscrop was superintendent of the Office of Commercial Deed. According to his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was a Freemason; members of his lodge were invited to participate in funeral rites for him. Mosscrop’s obituary in The New York Times indicates that he had lived in Brooklyn for more than 60 years. His last address was 220 Brooklyn Avenue in Brooklyn. Section 21, lot 16232, grave 1.

MOSSMAN, WILLIAM (1822-1872). Private, 170th New York Infantry, Company B; 2nd Battalion, Veteran Reserve Corps. Originally from Edinburgh, Scotland, he enlisted on August 11, 1862, at New York City, and mustered into the 170th on October 7. As per his muster roll, he was a watch and clock maker who was 5′ 7½” tall with grey eyes, brown hair and a light complexion. His muster roll also notes that he was the company cook in August 1863. Mossman was wounded on June 22, 1864, at Weldon Railroad, Virginia, and discharged for disability on an unstated date. Mossman’s pension index card reports additional service in the 38th Company of the 2nd Battalion, Veteran Reserve Corps. On May 23, 1865, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 62,328.

Mossman became a naturalized citizen on October 27, 1865; at that time, he listed his occupation as watchmaker. He last lived at 62 Fulton Street in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to “congestion of the brain.” His widow and three children, who lived in Montreal, Canada, were awarded the $200 of his personal estate from the Surrogate Court of Brooklyn; he left no will. Sarah Mossman applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1890, certificate 346,500. Section 156, lot 20591.

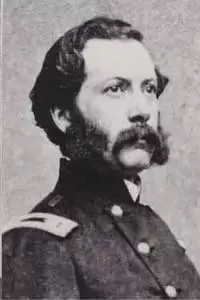

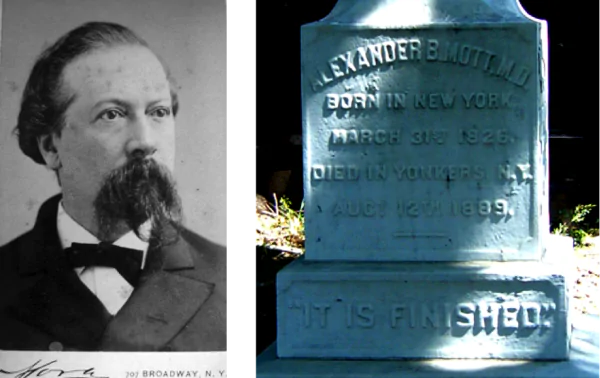

MOTT, ALEXANDER BROWN (1826-1889). Lieutenant colonel by brevet; chief surgeon, United States Volunteers Medical Staff. Born in New York City and the son of the renowned surgeon Dr. Valentine Mott (see), he traveled to Europe at age ten to receive a classical education before returning home to study medicine, first in his father’s office and then at the University Medical College and the Vermont Academy of Medicine from which he graduated with honors in 1850. Mott married in 1850 and then returned to New York City to practice medicine. He became a surgeon, working at Bellevue, St. Vincent’s, Jewish, Charity, and Mt. Sinai Hospitals in New York City. According to his obituary in the New York Herald, which confirms his Civil War service, he was appointed attending surgeon at Bellevue Hospital in 1859, and subsequently consulting surgeon to the Bureau of Medicine and Surgical Relief to the Out Door Poor of New York.

Mott’s service to the Union began at the onset of the Civil War. As per Camp and Field Life of the Fifth New York Volunteer Infantry (Duryee Zouaves), Mott examined the men on May 9, 1861, before they set out for Virginia, rejected a few and said that “a finer body of men could not be found in Christendom.” He enlisted as a surgeon on November 7, 1862, and was immediately commissioned into the Medical Staff of the United States Volunteers. Mott was named Medical Director of the Department of the East, organized the United States Army General Hospital in New York City, and was its chief surgeon with the rank of major. In 1864, he became medical inspector of the Department of Virginia where he was attached to the staff of General Edward O. C. Ord, and was at the conference between Grant and Lee at Appomattox where the terms of surrender were arranged. On June 1, 1865, he was brevetted to lieutenant colonel for “faithful and meritorious service.” He mustered out on July 27, 1865.

Dr. Alexander Mott was a founder of Bellevue Medical College, was a professor of clinical and operative surgery there, and retired from the chair of surgical anatomy in 1872. Among his special interests were hydrophobia, and surgeries of the carotid artery, hip joint and jaw. Known as “genial and gentle,” he was held in high esteem by colleagues and acquaintances. According to his obituary in the New York Herald, he was a member of many fraternal organizations, including the Freemasons, of which he was a 33rd degree Mason, and the Old Guard Veteran Battalion. He held the positions of surgeon and junior vice commander of the James C. Rice Post #29 of the G.A.R.

The New York Tribune reported on his funeral at Trinity Chapel on August 16, 1899, and noted that a large number of guests were from the medical profession and from the various civil and military organizations of which he was a member. The procession was led by members of the Mott family followed by the faculty of Bellevue Hospital Medical College, faculty of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Old Guard, Loyal Legion (a patriotic association of officers of the Civil War), Grand Army posts, and Masonic bodies. A resident of New York City, he died at his country home in Yonkers, New York. His obituary in the New York Herald noted that he died two days after he contracted pneumonia. Section 98, lot 6035.

MOTT, VALENTINE (1785-1865). Pioneer surgeon. The son of a distinguished doctor, he was born in Glen Cove, New York. Mott received a classical education at a seminary in Newtown, Long Island. After graduating from Columbia College in 1806, he traveled to Europe where he studied anatomy and surgery in London and Edinburgh with the greatest teachers of the day. He returned to New York in 1809, and was soon named a professor of surgery at his alma mater. Subsequently, he taught at the College of Physicians and Surgeons and Rutgers Medical College (which he helped to found), and was a founder of the medical department of the University of the City of New York (later New York University Medical College). For many years he held positions of senior consulting surgeon at Bellevue, St. Luke’s, Hebrew, St. Vincent’s, and Women’s Hospitals, and earned the reputation as America’s greatest surgeon.

Dr. Valentine Mott had world-wide renown as a pioneer of new surgeries, including amputation at the hip joint (he amputated over 1,000 limbs during his career), excising the jaw for necrosis, and surgery of the veins. Operating in an era before anesthetics, he was very quick and ambidextrous. He long maintained his practice of trying out these new operations on cadavers before operating on patients and was said to have performed more of the great operations than any other man in the world up to his time. His reputation was so widespread that he was summoned, while traveling abroad, to operate on the Sultan of Turkey. He also invented many surgical and obstetrical implements.

After surgical anesthesia was introduced in 1846, Mott became an authority on the subject, and wrote Pain and Anesthetics (1862) at the request of the Sanitary Commission for use by Civil War surgeons. His support of the work of the Sanitary Commission, an organization on which he served as a board member, gave the women’s relief organization a more powerful voice. Dr. Mott edited Surgical and Medical Essays (1863) for physicians in the Union Army. He served as president of the New York Academy of Medicine and the New York Inebriate Asylum. According to one report, he grew so agitated upon hearing of Lincoln’s death that he took to bed and died twelve days later on April 26, 1865. His son, Alexander Brown Mott (see), was a chief surgeon at the United States Army General Hospital in New York City. Section 98, lot 6035.

MOTTRAM, MATTHEW (enlisted as MIDDLETON, WILLIAM) (1814-1862). Private, 36th New York Infantry, Company K. A native of England, Mottram was borne on the rolls as William Middleton. He enlisted as a private at New York City on June 19, 1861, and mustered into the 36th New York on June 24. His muster roll reports that he was paid by the State from May 19 through June 23, 1861, for one month and five days, the sum of $12.50 for his service. On February 18, 1862, he died of typhoid fever at the Camp Hospital in Brightwood, District of Columbia. His name, under his alias of William Middleton, appeared in the Bodies in Transit List as passing through New York on March 27, 1862; he was interred the next day. Mary Mottram, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension on February 4, 1864, certificate 40,038. Section 94, lot 589.

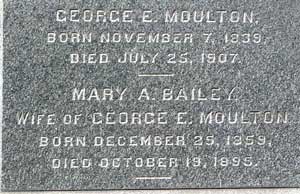

MOULTON, GEORGE EDWIN (1839-1907). Captain, 13th Maine Infantry, Company A; 30th Maine Infantry, Company B. A native of Piscataquis, Maine, Moulton was educated at Westbrook Seminary and entered Tufts College in 1852. In 1859, he entered Bowdoin College, but enlisted in the Civil War before completing his studies. Moulton enlisted as a private at Augusta, Maine, on October 7, 1861, mustered into the 13th Maine, and was promoted to second lieutenant on November 20. The 13th Maine was in Ship Island, Louisiana, from March-July 1862, and then occupied Fort Jackson in that state.

Subsequently, his unit was part of the expedition to Texas in October 1863, took Brownsville on November 5 of that year, Point Isabel the next day, and Mustang Island on November 15. In 1864, the 13th Maine was engaged in the Red River Expedition from March 10-May 22, including skirmishes in Louisiana at Sabine Cross Roads on April 8; Pleasant Hill on April 9; and Mansura on May 16. Moulton became a first lieutenant on October 14, 1864, and rose to captain on an unspecified date. When the 13th was consolidated into the 30th Maine, he joined the 30th as a captain on December 27, 1864, and was detached to guard supply trains during the Shenandoah Campaign under General Sheridan in 1864-1865. He was discharged at Savannah, Georgia, on August 20, 1865, where he had been at headquarters beginning on June 7.

After his service, he completed his studies and received his degree. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which confirms the details of his service in the Civil War, Moulton moved to Chicago, Illinois, after the War and was in the lumber business there. He settled in Brooklyn in the mid 1870s and was active in church and political life. He was superintendent of All Souls Sunday School in Brooklyn’s Eastern District and was grand marshal of its anniversary parade on numerous occasions. In addition, he had served as treasurer of the Eastern District Sabbath School Association and the Homeopathic Dispensary on South 3rd Street. The New York Tribune reported on May 22, 1895, that Mayor Charles A. Schieren (who is also buried at Green-Wood) had appointed four men, one of whom was Moulton, as Election Commissioners; the term was five years at a salary of $4,000 per year. That article indicated that Moulton had been president of the Thirteenth Ward Republican association for ten years, was a member of the Union League Club, was president of the Kings County Building and Loan Association, and has been connected for twenty years with the Bradstreet Company. An article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on October 19, 1895, reported that Moulton, then president of the Board of Elections, faced the sudden death of his 36-year-old wife, May (Mary) Bailey Moulton, who is interred with him, due to an internal hemorrhage; Mrs. Moulton was a lifelong member of the All Souls Universalist Church.

On April 21, 1896, the New York Tribune reported that Moulton, an expert fisherman, and Election Commissioner Benjamin Blair went on a fishing trip to Massapequa, Long Island. Blair and a young boy, his guide, were on a raft when the raft overturned, sending the two into the stream. Blair, a non-swimmer, was saved by Moulton who dove into the waters and helped bring Blair back to the raft; the young boy swam safely to shore. Blair praised Moulton for saving his life. An article in The New York Times on March 9, 1902, reported that Moulton had married a second time, in December 1901, at the First Methodist Episcopal Church on Manhattan Avenue in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle also notes that Moulton was a member of the Board of Education. A member of the Henry M. Lee Post #21 of the G.A.R., Moulton held several offices including chaplain. In 1905, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 1,104,774. He last lived at 929 Greene Avenue in Brooklyn. His death was caused by cancer. In 1924, his second wife, Eliza Brower, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 959,911. Section 197, lot 29336, grave 5.

MOULTON, WILLIAM S. (1827-1885). First lieutenant, 4th New York Infantry, Companies E and G. Moulton enlisted at New York City as a first lieutenant on April 22, 1861, was commissioned into Company E of the 4th New York on May 2, and resigned on July 6 of that year. Upon his second enlistment on December 17, 1861, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant into Company G of the same regiment, and resigned on February 26, 1862. His last residence was 158 East 118th Street, New York City where he died of pneumonia. Section 44, lot 5367.

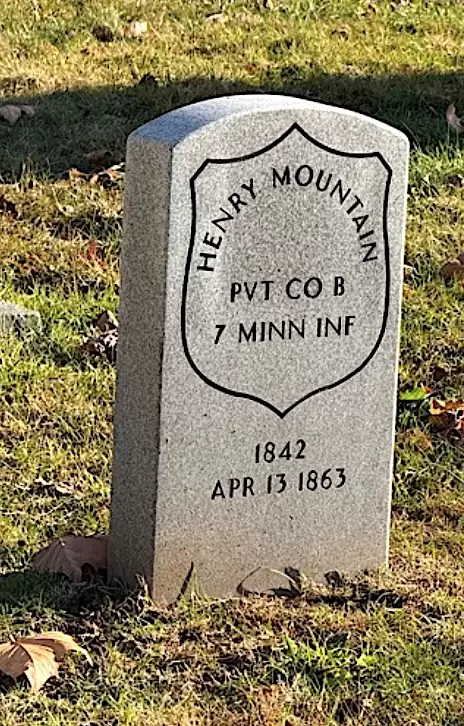

MOUNTAIN, HENRY (1842-1863). Private, 7th Minnesota Infantry, Company B. Mountain was born in England and then resided in Brooklyn before he went West and enlisted and mustered into the 7th Minnesota Infantry on August 17, 1862. He died from lung disease at Fort Tivoli Barracks, Minnesota, on April 13, 1863. An article in the May 28, 1890, edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle relates that when he died during the War a memorial inscription that was etched on a cracker box by a comrade was placed over his body. Mountain was then interred at Green-Wood along with the pen-knifed memorial homage. This account in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the placement of tributes to veterans on Decoration Day by Joseph Woodward (see), a G.A.R. member. Section 22, lot 8363.

MOUNTFORT (or MOUNTFORD, MONTFORD), STUYVESANT S. (1833-1875). Private, 71st Regiment, New York State Militia, Company E. Born in New York City, his parents were from Massachusetts; his father’s family settled in Boston in colonial times and were prominent merchants there. The census of 1850 and the 1855 New York State census report that he was living with his parents in New York City; Mountfort was working as a clerk in 1855. A son of Judge Napoleon B. Mountfort of the New York City Police Court, Stuyvesant Mountfort was one of three brothers who fought in the Civil War. Stuyvesant served alongside his brother, William Mountfort (see), in the 71st Regiment from April 21, 1861, when the unit headed for Washington, D.C., until he mustered out with his company after three months on July 31, 1861. Details about the third brother, Joseph Mountfort who also served in the Civil War, are not known.

The New York State census of 1865 indicates that he was a boarder living in New York City. The 1875 New York State Directory lists Mountfort as a clerk. As per his death certificate, he was single and worked as a salesman. On September 5, 1875, an article about Mountford’s (sic) death was published in the New York Herald; that article attributed his death to suicide; an almost-empty bottle of laudanum (a tincture of opium) was found near his body. The New York Times reported that same day that Mountfort (spelled Montford in the report) was a photographer who had not been regularly employed; the article noted that his body was found swollen beyond recognition. An article in the Daily Tribune on September 6, 1875, noted that the coroner held an inquest on Mountfort’s body (again spelled Montford in the article). He last lived at 112 East 22nd Street in Manhattan. Section 164, lot 16332.

MOUNTFORT, WILLIAM H. (1836-1896). Private, 71st Regiment, New York State Militia, Companies E and H. A native New Yorker, Mountfort’s father, Napoleon Bonaparte Mountfort, a New York City judge of the Police Court, traced his roots to a prominent Boston family that settled there in colonial times. As per the 1850 census and the 1855 New York State census, William was living with his parents and working as a druggist. An article in The New York Times on June 11, 1860 reports that Mountfort was elected chairman of the Garibaldi League, a group that was founded to raise money to support Giuseppe Garibaldi’s efforts to unify Italy.

During the Civil War, Mountfort enlisted at New York City as a private on April 21, 1861, mustered into Company E of the 71st New York State Militia, fought at Bull Run, Virginia, on July 21, and was discharged at New York City after three months on July 30. When he returned to the 71st Regiment’s National Guard on June 17, 1863, he served with Company H for 30 days before mustering out on July 20. His brother, Stuyvesant Mountfort (see), served in the same unit; another brother, Joseph Mountfort, also fought during the Civil War.

Mountfort married Sarah Frances Houghton on September 16, 1863; his marriage was announced in The New York Times and newspapers in Boston and Newburgh, New York. According to an article in the New York Tribune on May 7, 1870, he had just been elected secretary of the Union Republican County Convention. The census of 1870 notes that he lived in New York City and worked as an assistant agent at the Internal Revenue Service; at that time, he was a wealthy man: his real estate was worth $30,000 and his personal estate was valued at $10,000. The New York City Directory for 1872 lists him as an assistant assessor whose home address was at Broadway and West 26th Street. The 1880 census and the 1884 Brooklyn Directory report that he was a druggist living in Brooklyn. A member of the Henry M. Lee Post #21 of the G.A.R. as of October 23, 1879, he served as its surgeon from 1884-87. The G.A.R. Annual of 1897 confirms his military service. His obituary in the New York Herald notes that members of the Henry M. Lee Post were invited to attend his funeral; newspapers in Boston and Philadelphia were asked to post news of his death. He last lived at 126 Penn Street in Brooklyn. His death was caused by myelitis. Section 164, lot 16322, grave 8.

MOWBRAY (or MOUBRAY), ROBERT C. (1846-1895). Seaman, United States Navy. Mowbray was born in Ulster County, New York, and lived in Kingston, New York, at the time of the census of 1850 and the 1855 New York State census. After enlisting on August 12, 1863, he first served on the USS North Carolina, a receiving ship at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and then transferred to the USS New Hampshire at Port Royal, South Carolina, joining the South Atlantic Squadron, before being transferred to the Oleander. He returned to the New Hampshire before his last assignment on the Constitution School Ship at the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, from which he was discharged on August 14, 1866.

The 1875 New York State census reports that Mowbray lived in Brooklyn with his mother and siblings and was employed as an engineer. The Brooklyn Directories for 1878 and 1891 list him as a pilot (ship pilot). He received an invalid pension in 1891, based on total deafness in the left ear, certificate 22,187, but was dropped in 1895 as not “ratably disabled” because he supported himself by manual labor. His death certificate indicates that he worked as a pilot. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Mowbray was a member of the National Provident Union, a fraternal organization founded in 1883 that provided sick and death benefits to its members; members of his lodge were invited to attend his funeral. He last lived at 456½ 7th Avenue in Brooklyn. Mowbray’s cause of death was listed as asthenia, a loss of strength. Section 142, lot 22397, grave 4.

MUELLER (or MULLER), WILHELM (1834-1897). Private, 7th New York Infantry, Company C. A native of Germany, he enlisted as a private on April 23, 1861, at New York City, and mustered in the same day. He was taken as a prisoner of war on July 1, 1862, at White Oak Swamp, Virginia, was paroled on September 13, 1862, at a place not specified, and was discharged for disability on February 25, 1863, at Camp Banks, Virginia. His last residence was at 202 East 36th Street, New York City. Mueller died from heart disease. Section 135, lot 27263, grave 1471.

MUIR, JOHN (1841-1920). Private, 79th New York Infantry, Companies H, B, C, and F. Born in New York City, Muir enlisted there as a private on May 28, 1861. On September 5, 1862, he re-enlisted in the 79th and mustered into Company H. On October 18, 1862, he was transferred into Company F at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. He mustered out on May 30, 1865. According to his pension record, he also saw service in Companies B and C, dates unknown.

According to the 1870 census, Muir lived in Brooklyn and worked as a bank clerk. The 1885 Brooklyn Directory lists Muir as a broker; the 1904 Brooklyn Directory lists him as a real estate broker whose home address was 823 Beverley Road. In 1908, he applied for and was granted an invalid pension, certificate 1,150,744. At the time of the 1910 census, Muir lived in Brooklyn and worked in real estate; the 1920 census indicates that he lived with his son and had his own business in real estate. His obituary in The New York Times, which confirms his Civil War service, reports that he was a real estate agent; he died suddenly at the elevated subway stop at Adams Street. Muir’s death certificate notes that he was single and worked as an insurance agent. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, his funeral took place at the First Christian Church at 241 Park Place in Brooklyn. His last residence was at 162 68th Street in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. Section 69, lot 11510.

MUIR, JOHN (1842-1925). Private, 79th New York Infantry, Company C. Of Scottish origin, Muir immigrated to the United States in 1858. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a private at New York City on May 13, 1861, and mustered into the 79th New York Infantry—composed mainly of Scots and known as the Highlanders–on May 28, 1861. He was taken as a prisoner of war at Bull Run, Virginia, on July 21, 1861, and was discharged on May 24, 1862, at Washington, D.C.

The 1880 census reports that Muir was a plumber and the 1900 census indicates that he was a master plumber; he lived in Manhattan at the time of those censuses. He filed for a pension in 1907, certificate 1,133,375. The 1910 census indicates that he had his own plumbing business. As per his death certificate, he was a widower and worked as a plumber. His last residence was at 2332 University Avenue in the Bronx. He succumbed to lobar pneumonia. Section 181, lot 11868, graves 4 and 5.

MULDOON, JOHN (1841-1873). First lieutenant, 6th New York Cavalry, Companies I and L; 2nd New York Provisional Cavalry, Company L. As per the 1860 census, Muldoon, a native of New York, lived in Caneadea, New York. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a sergeant at Angelica, New York, on November 3, 1861, and mustered into the 6th New York Cavalry on November 15. His muster roll notes that he had blue eyes; no other physical characteristics were indicated. Wounded in battle, he was taken as a prisoner of war on August 20, 1862, at Culpeper, Virginia, and paroled the next month on September 13.

After Muldoon re-enlisted as a veteran on December 16, 1863, he was promoted to first sergeant that day. The Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War states that he received a bounty of $300 when he re-enlisted—that is the equivalent of $5,628.10 in 2017. According to his muster roll, he was absent and sick from wounds at Baltimore, Maryland, on October 31, 1864; the muster roll reports “the date and place of wounds not stated.” Muldoon was promoted to first lieutenant on November 1, 1864, effective upon his transfer to Company L on December 1. On June 17, 1865, he was transferred into the 2nd New York Provisional Cavalry where he served until he mustered out at Louisville, Kentucky, on August 9.

As per the New York City Directories for 1869, 1872, and his death certificate, Muldoon was a grocer. Although he applied for an invalid pension in August 1872, application 177,320, it was never certified. He last lived at 172 South 3rd Street in Brooklyn. His death was caused by a brain tumor. Jemima Muldoon, who is interred with him, applied for a widow’s pension in July 1873, application 210,276, but it was never certified. Section 156, lot 20894.

MULHOLLAND, THOMAS HENRY (1846-1916). First lieutenant, 176th New York Infantry, Companies G and H. Born in Bermuda, he came to New York as a child. The 1860 census indicates that he lived with his family in New York City and was an apprentice to a wheelwright. During the Civil War, Mulholland enlisted as a private at New York City on September 13, 1862, mustered into Company G of the 176th New York on December 18, and was promoted to first lieutenant on December 21, 1863. On October 19, 1864, he was wounded at the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia. On December 22, 1864, he mustered out as a first lieutenant with a disability discharge as per Special Order #462 of the War Department. In 1867, his application for an invalid pension was granted, certificate 89,385.

Mulholland lived in Manhattan after the Civil War and then moved to Evergreen (North Brooklyn) in the mid 1880s. At the time of the 1880 census, he lived in Manhattan with his mother and siblings, and worked as a car builder. The Veterans Census of 1890 confirms his Civil War service; he is listed on that document as living in Evergreen, Long Island. An article in the Newtown Register (Queens, New York) on October 1, 1891, indicates that he was a member of the Board of Education there. Another article in the Newtown Register on September 28, 1893, notes that he was the chairman of the Newtown Republican Town Committee and was a delegate at the Town Convention. A subsequent article in the Newtown Register on September 15, 1898, reports that the Second Ward Republican Association met to endorse Theodore Roosevelt for governor of New York; Mulholland was selected as a delegate to the County Convention.

The Newtown Register reported on May 11, 1905, that Mulholland announced that real estate in the Evergreen community was “booming” and that he had sold several homes and lots there; he was listed as a real estate broker in the 1910 census. As per his obituary in the Newtown Register, which confirms his Civil War service, he worked for nearly fifty years at the Stevenson car manufactory (coach and street-car builders) in Manhattan where he held the position of foreman; he also carried on a real estate business in Ridgewood. His obituaries in the Brooklyn Daily Star and The New York Times confirm his Civil War service and note that he was a retired real estate agent. The New York Times obituary reports that he was a Freemason and a member of the Janes Methodist Episcopal Church for 30 years. He last lived at 1626 Decatur Street in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to arteriosclerosis. Mary Mulholland, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1916, certificate 818,124. Section 13, lot 19694, grave 179.

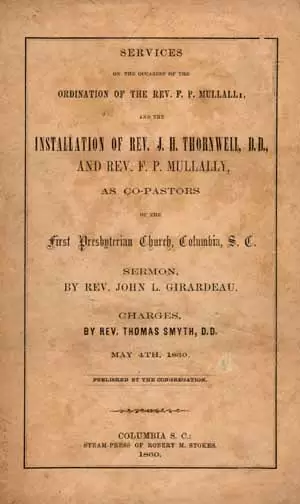

MULLALLY, FRANCIS PATRICK (1834-1904). Chaplain, 1st South Carolina Infantry, Company F, Confederate States of America. Born in Tipperary, Ireland, to a mother who was a daughter of Lord Mandeville, he was educated as a Presbyterian. He served as secretary to Smith O’Brien who was imprisoned in Dublin after leading an unsuccessful uprising in Tipperary. After his estate was confiscated and a price was put on his head, Mullally fled to the United States and settled in Georgia. He was educated at Washington and Lee University Law School and Columbia Theological Seminary before his ordination as a Presbyterian minister in Columbia, South Carolina, on May 4, 1860. In addition to his ministry, he wrote on religious subjects for church and secular publications.

Mullally enlisted as a private in the Confederate Army where he served as a chaplain with the 1st South Carolina, Company F, also known as Orr’s Rifles. According to his obituary in The New York Times, he was also a colonel with the regiment, a rank he achieved by promotions “for gallantry in action” and was known “…as the chaplain who fought as hard as he prayed.” In addition to ministering to the Confederacy, he preached to Union soldiers and conducted funeral services for federal officers.

After the Civil War, Mullally returned to the Presbyterian Church, serving in ten different locales. According to a descendant, he lived in Kentucky in 1870 and in Virginia in 1880 before moving to Manhattan in 1898. He last lived on Ely Avenue in Pelham Manor, New York. His death was attributed to oedema of the lungs. Section 196, lot 30319, graves 8 and 9.

MULLEN, JOHN (1847-1923). Private, 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery, Companies L and G. Mullen was born in Ireland. As per census data, his family immigrated to the United States in 1851 or 1852. According to a descendant, he enlisted at New Haven, Connecticut, when he was a teen-ager, served with the 2nd Connecticut Artillery, and fought at the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, at Little Roundtop on July 2, 1863, and at the stonewall on July 3.

Mullen is listed on the National Park Service website as being part of the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery. His soldier record indicates that he was a resident of Bridgeport, Connecticut, when he enlisted as a private on February 2, 1864, and mustered into the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery that same day. That unit was reorganized in November 1863, and joined the Army of the Potomac where it engaged in many of the battles of the Civil War including but not limited to these in Virginia: Petersburg (1864 and 1865), Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna River, Hanover Court House, Cold Harbor, Snicker’s Gap, Winchester, Opequan, Cedar Creek, Strasburg, and Hatcher’s Run. After an intra-regimental transfer to Company G on July 20, 1865, he mustered out a month later on August 18 at Fort Ethan Allen, Washington, D.C.

The 1900 census reports that Mullen lived in the Bronx in a rental with his wife and two sons, had been married for 19 years, was a naturalized citizen and worked as a fireman. In 1904, Mullen’s application for a pension was approved, certificate 1,103,192. The 1905 New York State census reports that he lived in Brooklyn with his wife and a twenty-year old son. The 1910 census states that he was living on St. Mark’s Place in Brooklyn with his wife of 29 years and adult son, was a Union Army veteran, and a retired firefighter. The 1915 New York State census reports that he still lived in Brooklyn with his wife and son. At the time of the 1920 census, he lived on St. Mark’s Place in Brooklyn with his wife. He was survived by his wife, Annie, who is interred with him. In 1926, Annie Mullen applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 940,138. Section 131, lot 33434, grave 2.

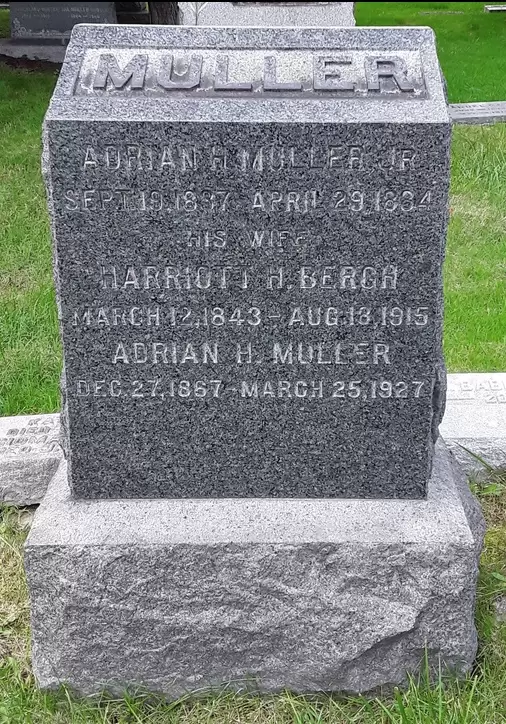

MULLER, JR., ADRIAN HERMAN (1837-1884). Private 7th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company H. Adrian was born in Geneva, New York, on September 15, 1837. His birth in Geneva was documented in Dutch Reformed Church Membership Records. His Ancestry family tree names his parents as Adrian Sr. and Catherine Schermerhorn Abeel. North American Family Histories detail his mother’s marriage to Adrian Muller and name five siblings of Adrian: William, Margaret, Elizabeth, Joanna, Mary; Kate (Cate) and Julia, who are named on the 1855 census, are not listed in this document.

As per his family tree, the Mullers were living in New York City by 1855. The New York State census of 1855 lists Adrian as a child (17) living with his parents in New York City with siblings: Kate, Margaret, Joanna, Mary, Julia, William and Elizabeth, and three others, relationship unknown. Adrian’s name is listed in the Class of 1856 of the New York City Free Academy. At the time of the 1860 census, Adrian was living with his parents, siblings and two unrelated adults surnamed Loftus; siblings, Kate and William, are not listed.

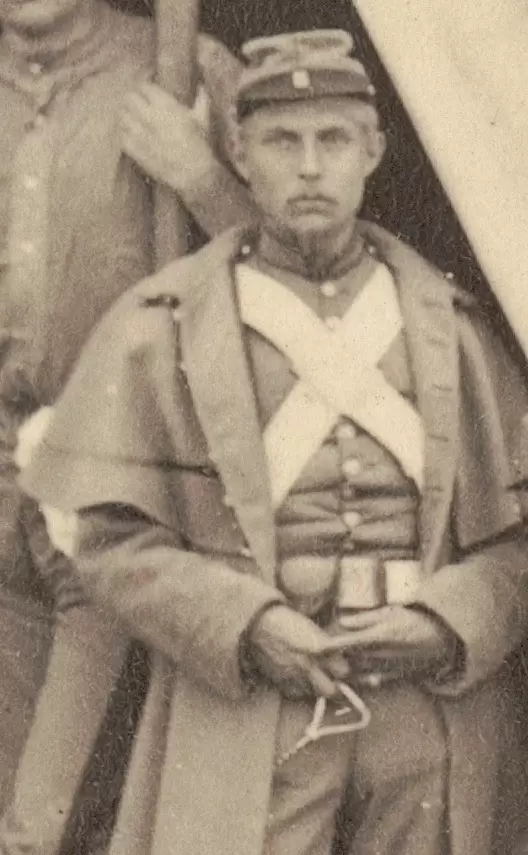

During the Civil War, Muller served during two activations of the 7th Regiment. According to the History of the Seventh Regiment of New York, 1806-1889, by Colonel Emmons Clark, Muller is named with other soldiers in Company H of the 7th Regiment in 1861. He re-enlisted at New York City as a private on May 25, 1862, and mustered immediately into Company H of the 7th New York National Guard, for its second activation. He mustered out with his company on September 5 at New York City.

On September 23, 1863, Adrian married Harriet Hoadley Bergh at the South Dutch Church in New York City. The couple had four children, one of whom died young: Julia (1865-1920), Adrian III (1867-1927), Joanna (1867-1868), and Charles (born 1867-no death date given). Their marriage is included in Dutch Reformed Church Records. The 1880 census shows Adrian and Harriet living at 58 East 36th Street in New York City with children Julia (16) and Charles (12); Adrian III is not listed.

Adrian worked with his father as an auctioneer. Both are listed as being in the auction business at 7 Pine Street in the 1884 New York City Directory. As per an advertisement in The New York Times on April 8, 1884, Adrian H. Muller and son were holding a real estate auction. The ad noted that the two were holding an executor’s sale for a building and lot on Sullivan Street and for numerous lots on Tenth Avenue and West 139th and West 140th Streets.

Adrian died in New York City on April 25, 1884; his death was attributed to phthisis (tuberculosis). His last address was 58 West 36th Street in New York City. Muller is buried in an underground vault at Green-Wood with no marker. His will was probated in New York City on May 13, 1884. Names listed on the will were: Harriet Muller (wife); Mary Muller (aunt); Charles (son); and Charles Isham (brother-in-law). A cenotaph honoring his memory is at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Section 7, lot 14210.

MULLER, ANTON (1826-1876). Corporal, 54th New York Infantry, Companies G and K. Originally from Germany, Muller enlisted as a private at Hudson City, New Jersey, on September 17, 1861, mustered into Company G of the 54th New York and then transferred to Company K on the same day. During his service, he was promoted to corporal at some point only to be reduced in rank to private at a later date. He mustered out on October 24, 1864, at New York City. Muller last lived at 245 State Street in Brooklyn. The cause of his death was pneumonia. Section 121, lot 7639, grave 267.

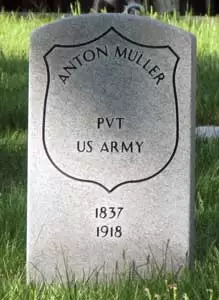

MÜLLER (or MILLER), ANTON (1837-1918). Sergeant, 158th New York Infantry, Company E. Born in Germany, he immigrated to the United States in 1854. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a private at Brooklyn on August 22, 1862, and mustered into Company E of the 158th New York nine days later. He was promoted to corporal on January 15, 1864, and to sergeant on January 1, 1865. Müller mustered out on June 30, 1865, at Richmond, Virginia. According to his muster roll, he was also borne on the rolls as Anton Miller. He was a baker by trade who was 5′ 8″ tall with blue eyes, dark hair and a fair complexion. Müller’s muster roll notes that he was hospitalized in New Berne, North Carolina, in June 1863, and returned to the rolls in August. He was promoted to corporal on January 15, 1864, and to sergeant on January 1, 1865. Müller mustered out with his company on June 30, 1865, at Richmond, Virginia. According to the Veterans Schedule of 1890, a census of Civil War veterans, he stated that he had dislocated his shoulder during his service.

The census of 1880 reports that Müller was married, lived in Brooklyn, and worked as a baker; the Brooklyn Directory for 1883 listed him as a baker at 303 Graham Avenue. In 1890, he filed for and received an invalid pension, certificate 900,991. The 1904 Brooklyn Directory lists him as a baker. As per the 1910 census, Müller was a widower who lived on Russell Street in Brooklyn, was a naturalized citizen, worked as a laborer at the Navy Yard, and could read and write. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Standard Union, which confirms his Civil War service, he was a member of the Barbara Frietchie G.A.R. Post #11 of Greenpoint, Brooklyn. His last residence was at 56 Russell Street in Brooklyn, where he died of senility. As per his will, filed in Brooklyn, he left no descendants and his estate totaled about $4,000, the equivalent of about $65,000 in 2017. An article about his estate in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on June 20, 1918, reports that he bequeathed his step-daughter his household furniture, piano, and silverware; his two grandchildren were bequeathed the remainder of his estate. Section 14, lot 19438, grave 165.

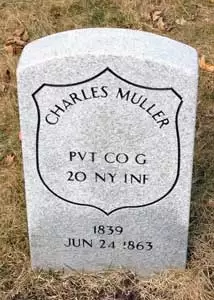

MULLER, CHARLES (1839-1863). Private, 20th New York Infantry, Company G. A native of Germany, he enlisted as a private at New York City on July 5, 1861, mustered into the 20th that day, and mustered out at New York City on June 1, 1863. He lived for less than a month at 90 Chrystie Street in Manhattan where he died from typhoid fever on June 24. Section 115, lot 13536 (Soldiers’ Lot), grave 64.

MÜLLER, JACOB (1826-1891). First lieutenant, 55th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company F. Of German birth, Müller at some point served in the Prussian Army. He enlisted as a first lieutenant at New York City on June 24, 1863, and was commissioned into the 55th Regiment’s National Guard that same day. He mustered out with his company after 30 days on July 27 at New York City.

The 1875 New York State Census and the 1880 census report that Müller was a “liquor barkeeper”; the 1878 Brooklyn Directory reports that he was in the liquor business at 116 Sackett Street. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was a Freemason and member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows; members of both organizations were invited to attend his funeral. He last resided at 18 Tompkins Place in Brooklyn. His death was caused by nephritis. Section 199, lot 25007, grave 25.

MULLIGAN, JAMES BRECKINRIDGE (1833-1912). Lieutenant colonel and major by brevet; captain, United States Volunteers Aide-de-Camp; 19th Infantry, United States Army. Born in New Hampshire, Mulligan enlisted as a captain on April 30, 1861, and was commissioned that day into the United States Volunteers as captain and aide-de-camp for the New Jersey Militia. He mustered out on July 30 and became a captain in the 19th Infantry of the United States Army on October 26, 1861.

An article in the Philadelphia Inquirer on October 28, 1862, headlined “Important From Tennessee,” reported that Mulligan was appointed by General James S. Negley to command all the non-commissioned officers of the 15th, 16th, 18th and 19th Infantries and those members of Terrill’s and Mendenhall’s Batteries not assigned to special duty. He was tasked with the job of impressing “all the wagons and negroes he could find for the purpose of working on the fortifications.” Between 200-300 black men were involuntarily impressed into service in about two hours. The article described some of the scenes that occurred during this impressment: a black man dressed for his wedding was seized on his way to his bride’s house; one man was shot while trying to escape; black men were seized from barber shops and while playing or serving as attendants for a faro card game; and servants at hotels were grabbed up. The article noted that many of the black men who were seized, whether Confederates or Union, were not happy about being forced to perform hard labor near Fort St. Cloud.

Mulligan was brevetted to major on September 20, 1863, for his leadership at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and Chickamauga, Georgia. A year later, he was brevetted to lieutenant colonel on September 1, 1864, for his service in the Atlanta Campaign and the Battle of Jonesboro, Georgia. He resigned from the United States Army on August 31, 1869.

In civilian life, he was associated with a business firm in Manhattan. The 1880 census indicates that he was living with his wife and children in Elizabeth, New Jersey, at the residence of his brother-in-law, Robert Stockton Green (who was governor of New Jersey from 1887 through 1890); no occupation is listed for Mulligan. The 1889 New York City Directory notes that he was a deputy collector living in Elizabeth, New Jersey; at that time, the Internal Revenue Service reported his income as $1,400 per year. The 1894 New York City Directory reports that he was still a deputy collector living at 201 West 13th Street in Manhattan.

An article in the Duluth Evening Herald on May 2, 1902, brought to light a controversial incident in Mulligan’s past. Apparently, Mulligan was married and had a young daughter named Minnie when he was stationed at Fort Smith, Arkansas, after the Civil War. About 1870, when he was ordered East with his regiment, he left his wife and daughter behind and never saw them again. According to the newspaper feature, Minnie, a mother of three young daughters, recalled that her mother remarried after receiving a letter that her husband was dead; Minnie was reared by her step-father and was known as Minnie Roberts by the Cherokee nation. Minnie asked a friend in the Tahlequah Indian Territory to investigate whether her father ever left an estate in New York and when she discovered that her father was alive, hoped to have a reunion with him after thirty-two years; Mulligan was then living at the same address on West 13th Street.

In 1905, Mulligan’s application for a pension was approved, certificate 1,110,657. His obituaries in the New York Herald and the New York Press confirm his Civil War service and note that he was the brother-in-law of the late Robert S. Green, a former governor of New Jersey. (Green and his wife are interred in the same lot at Green-Wood as Mulligan.) His last residence was at 1129 East Jersey Street in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Arteriosclerosis was the cause of his death. Mary E. Mulligan, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1912, certificate 770,990. Section 13, lot 8951.

MULVEY, ROBERT A. (1844-1886). First sergeant, 1st New York Infantry, Company A. Of Irish birth, Mulvey enlisted as a private at New York City on April 22, 1861, mustered into the 1st New York the next day, and was simultaneously promoted to sergeant. On October 27, 1862, he was promoted to first sergeant and mustered out of service on May 25, 1863, at New York City.

The 1867 New York City Directory and the 1870 census list Mulvey as an engineer. As per the 1874 New York City Directory and the 1880 census, he was a horse carman; the 1877 New York City Directory indicates that he was a conductor. According to his death certificate, he was widowed and had been a horsecar driver. His last residence was 854 8th Avenue in Manhattan. The cause of his death was pneumonia. In 1890, an application for a minor’s pension was approved, certificate 383,631. Section 15, lot 17263, grave 1305.

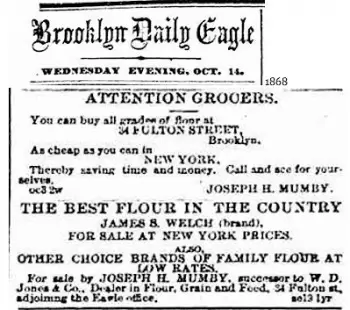

MUMBY, JOSEPH HAMILTON (1828-1918). Regimental quartermaster, 13th Regiment, New York State Militia Heavy Artillery. Born in Georgetown, D.C., Mumby’s family moved to Brooklyn when he was a youngster. Robert Mumby, his father, along with Abbott Low, founded the First Unitarian Church on Pierrepont Street in Brooklyn Heights. Mumby was among those who traveled to California in 1849 hoping to become wealthy in the Gold Rush. As per his passport application of 1849, he was 5′ 8″ tall with grey eyes, black hair, dark complexion, short chin, large nose, large mouth, low forehead and full face. He traveled to California by way Mexico and rode on horseback from Vera Cruz to San Francisco. After maintaining a trading post in California for a few years, he returned to Brooklyn in 1852. He married Tabitha Tagg in 1854; their marriage was recorded in The Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy. The 1860 census notes that he was a master baker; his personal estate was valued at $12,000.

An article in the New York Daily Tribune on August 8, 1861, reported that the officers of the 13th Regiment exchanged harsh words that resulted in a melee at the Law Office of General Crooke. Mumby was in the thick of it and after a warrant was issued for his arrest, he counter-sued Colonel Abel Smith; the result of the investigation into the disturbance was not given but the article noted that the event “created almost as much excitement in Brooklyn as the Battle of Bull Run.” The New York Daily Tribune reported on April 24, 1862, that the 13th Regiment held a parade celebrating the first anniversary of their departure to Baltimore and carried a flag given to them by the ladies of that city. About 120 men marched in the parade; Mumby was listed as the quartermaster of the regiment.

One month later, Mumby enlisted at Brooklyn as a quartermaster on May 28, 1862, and was commissioned into the Field and Staff as regimental quartermaster of the 13th New York State Militia Heavy Artillery. He mustered out at Brooklyn after three months on September 12. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which confirms his Civil War service, reports that he was on the staff of General Benjamin Butler at New Orleans.

In civilian life, Mumby was employed in the flour, grain and feed business, and also was an assessor in Brooklyn for ten years. His first grain business was in a building shared with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle; his business later moved to the corner of Columbia Heights and Fulton Streets when the newspaper needed more space. The 1870 census lists him as in the flour and grain business; his real estate was valued at $25,000 and his personal estate was worth $13,000. Among his remembrances of Brooklyn that were noted in his obituary were the old Brooklyn City Railroad, a horsecar line, and the successful opposition of members of the Plymouth Church to the expansion of a large market on Fulton Street. He lived on Willow Street in Brooklyn before moving to Baldwin, Long Island, in the mid 1890s and where he owned many properties. The Veterans Census of 1890 confirms his Civil War service. The 1900 census notes that he lived in Hempstead, New York, and was a retired produce dealer.

A Democrat, Mumby was active in the civic and political life of his Long Island community. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that he kept up with the news and world affairs until his last days; he was proud that he had lived through three wars and hoped to see the United States and the Allies victorious in the World War. He reportedly told his daughter that it looked as though “America was going to whip the stuffing out of the Huns.” He last resided in Freeport, Long Island, prior to his death at age 91. His death was attributed to arteriosclerosis. Section 166, lot 24263.

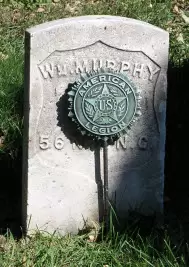

MUNDELL, CHARLES WILLIAM (1845-1865). Second lieutenant, 56th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company F. A New York native, Mundell lived with his parents in Brooklyn at the time of the censuses of 1850 and 1860. On June 18, 1863, he enlisted at Brooklyn and was commissioned the same day into Company F of the 56th Regiment as a second lieutenant. The 56th Regiment was ordered to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to meet the invasion by General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, and served in the Third Brigade, 1st Division, Department of the Susquehanna. On July 24, 1863, he mustered out at Brooklyn at the expiration of his 30 day enlistment. The 1864 Brooklyn Directory lists him as a clerk; his home address was 151 Sands Street in Brooklyn. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, friends and relatives were invited to attend his funeral at his parents’ home at 321 Bridge Street, Brooklyn. Mundell died of pleuritis. Section 95, lot 5525.

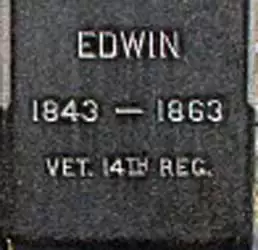

MUNKENBECK (or MOUNKENBICK), EDWIN (1843-1863). Private, 84th New York (14th Brooklyn) Infantry, Company K. Originally from England, Munkenbeck immigrated to the United States from London on the passenger ship Mediator, arriving in New York on April 7, 1847. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a private at Brooklyn on August 19, 1862, and mustered into the 14th Brooklyn the next day. As per his muster roll, Munkenbeck was a clerk who was 5′ 5½” tall with blue eyes, dark hair and a dark complexion. He was discharged for disability on February 14, 1863, at Convalescent Camp, Virginia. Two months later, he succumbed to typhoid fever, which he had contracted while in the line of duty. His obituary in the New York Herald, which confirms his Civil War service, notes that his funeral was held at the home of his parents at 109 Madison Avenue in Manhattan. Section 146, lot 25128.

MUNN, JOHN (1842-1918). Corporal, 28th New Jersey Infantry, Company F. Originally from New Jersey, Munn enlisted as a corporal at Freehold, New Jersey, on August 30, 1862. On September 22, he mustered into Company F of the 28th New Jersey from which he mustered out on July 6, 1863 at Freehold. The 1870 census indicates that he was a dock worker; the 1880 census notes that he was a laborer. In 1908, he applied for an invalid pension that was granted under certificate 1,147,954. According to the 1910 census, he was a laborer at a warehouse. His obituary in the Brooklyn Standard Union, which confirms his Civil War service, reports that he had lived in the Erie Basin (Red Hook) section of Brooklyn for fifty years and had worked for the New York Dock Company. As per his death certificate, he was retired and was a widower. His last residence was 25 Wolcott Street in Brooklyn. The cause of his death was carditis. Section 2, lot 5499, grave 420.

MUNRO (or MUNROE), JOHN DICK (1837-1908). Private, 79th New York Infantry, Company C. Munro, who was born in Scotland, immigrated to the United States in 1855. On May 13, 1861, he enlisted at New York City and mustered into the 79th New York, also called the “Highlanders,” on May 28. He fought at First and Second Bull Run, Virginia; Antietam, Maryland; and Spotsylvania, Virginia. As per his muster roll, which lists him as John Munroe, he was a civil engineer who was 5′ 9″ tall with blue eyes, light hair and a light complexion. His muster roll notes that he was sick and hospitalized at Mound City, Illinois, on unknown dates and served on extra duty as a regimental armorer; he returned to his regiment from extra duty on October 18, 1863. He mustered out on May 31, 1864, at New York City.

In 1892, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 880,294. The 1900 census and the 1905 New York State census note that he lived at 484 13th Street in Brooklyn; the 1906 Brooklyn Directory lists him at the same address and reports that he worked as a clerk. As per his death certificate, he was retired. Maria Munro, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1908, certificate 660,868. Section 147, lot 21981.

MUNROE, BENJAMIN FRANKLIN (1831-1904). Acting assistant paymaster, United States Navy. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, and a resident of that city in his early years, Munroe’s service in the United States Navy was recorded in the New York Herald on October 15, 1893, in an article headlined, “War Veterans of Wall Street.” He began his service in May 1861, as a clerk to Captain William Mervine, the flag officer of the USS Colorado in the Gulf Blockading Squadron, and remained in that position until after the capture of New Orleans, Louisiana (which occurred on May 1, 1862). He re-enlisted as an acting assistant paymaster on September 7, 1863, was commissioned into the Navy that day and assigned to the USS Supply, a storeship stationed off Charleston, South Carolina, where he was the paymaster and in charge of the ship’s stores (supplies). In November 1864, he was transferred to the USS Nereus on special service and took part in Naval assaults on Fort Fisher, North Carolina, as part of the South Atlantic Squadron. The Nereus was assigned to the West Indies at the close of the Civil War. He mustered out on August 27, 1865.

When Munroe applied for a passport on March 24, 1878, he was 5′ 7¾” tall with hazel eyes, gray hair, a sallow complexion, square chin and oval face. Munroe was listed as a broker in the New York City Directories for 1879, 1885, and 1890. His wife, Elizabeth Boggs Munroe, who died in 1895 and who is interred with him, had been the president of the Packer Institute alumnae; the Packer Institute, which was founded in 1843 as The Brooklyn Female Academy and renamed in 1853 after a fire, was a highly regarded school for women in Brooklyn Heights (the school became co-ed in 1972). The Veterans Schedule of 1890 confirms his Civil War service. Munroe is listed as a stock broker living at 207 Lincoln Place in Brooklyn on the 1900 census; his seat on the Stock Exchange was sold in 1904. According to a family genealogy, he was a banker and member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion, a patriotic organization of former Civil War officers. As per his death certificate, he was widowed and was a retired banker. His last residence was 207 Lincoln Place in Brooklyn. His cause of his death was a tumor. His last will and testament, as filed in the Brooklyn Surrogate’s Court shortly after his death, indicates that his real property was valued at $5,000 ($120,716 in 2017) and his personal property was worth about $100,000 ($2,414,320 in 2017). Section 173, lot 21869.

MUNROE (or MONROE), JOHN (1846-1918). Commissary sergeant, 35th United States Colored Infantry (USCT), Company A. Listed as John Monroe on his soldier records, he was an African-American born in Beaufort, North Carolina. A house servant at the time of his enlistment, he was 5′ 11″ tall with black hair and eyes and a light complexion. Munroe entered service as a private at Beaufort on May 23, 1863, and received his first promotion to sergeant on June 5. According to the Company Descriptive Book for the 35th USCT, he enlisted for a term of three years, was present at the South Carolina engagements at John’s Island on July 9, 1864, and at Honey Hill on November 30 of that year.

The 35th was organized at New Berne, North Carolina, then was attached to Montgomery’s Brigade, District of Florida, Department of the South. As per the recruitment of newly emancipated slaves, General Benjamin Butler of the Union Army set out this policy regarding the freedmen: “The recruitment of colored troops has become the settled purpose of the Government. It is therefore the duty of every officer and soldier to aid in carrying out that purpose.” Posters in New Berne offered an expected bounty of $602 and a cash down payment of $350. Historians today conclude that the recruitment of freedmen added to their autonomy, advancement toward literacy and self-worth. The 35th went on to serve in South Carolina, Georgia and Olustee, Florida; although the freedmen fought gallantly at Olustee, a battle where Union soldiers were forced to retreat to Jacksonville, Southerners regarded “the negro troops, or at least a large portion of them, as ‘fugitives’ from the Carolinas and Georgia.” Confederate President Jefferson Davis referred to the African American soldiers as “robbers and criminals deserving death,” and ordered former enslaved men fighting with the Union to be “turned over to civil authorities in their home states, where slave rebellion whether suspected, plotted, or actively pursued, was uniformly a hanging offense.” Historians have noted that African American soldiers who were taken as prisoners of war, and their white officers, after the Battle of Olustee were subject to hatred, mistreatment, and even summary execution.

Although it cannot be determined if Munroe was a slave or a free black before his enlistment, he was literate, since that ability was a key factor (as well as skin tone) in granting promotions to non-commissioned officers in the USCT. Research on black recruitment in the Civil War indicates that he was taking care of the paperwork for his company by 1864 and was a witness in the issuing of clothing. He mustered out as a quartermaster sergeant, a promotion he received on May 1, 1865, at Charleston, South Carolina, as per Regimental Special Order No. 27.

The 1899 Brooklyn Directory lists him as a laborer; his wife, Margaret (Maggie) Munroe was listed in the same directory as a dressmaker; they lived at 94 Willoughby Avenue. In 1890, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 671,746. Active in his community, he was part of the committee of the Rosewood Club of the A.M.E. Church on Bridge Street in Brooklyn that organized an old-fashioned Southern concert to benefit the church’s building fund. Munroe, who lived in Brooklyn for more than half a century, was a member of the A.M.E. Bridge Street Church for forty-seven years and a trustee for seventeen years; his wife was a deaconess at the church. The 1900 census and the 1905 New York State census list the Munroes as living in Brooklyn with their two sons at the Willoughby Street address; he is listed as a carpenter and she as a dressmaker.