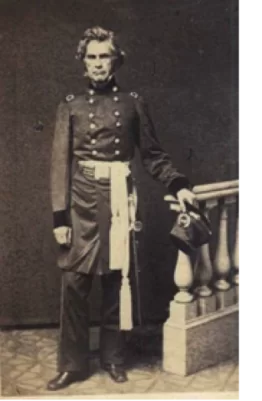

MITCHEL, EDWIN WILLIAM (1838-1873). Captain and assistant quartermaster, United States Volunteers Quartermaster’s Department; second lieutenant, 4th Ohio Cavalry. Originally from Ohio, he and his brother, Frederick Augustus (see), and father, Ormsby McKnight Mitchel (see), served together for part of the Civil War. He enlisted as a second lieutenant on January 11, 1862, and was commissioned into the Field and Staff of the 4th Ohio that same day. Upon his promotion to captain and assistant quartermaster on June 9, 1862, he was commissioned into the United States Volunteers Quartermaster’s Department where he served as a brigade quartermaster on his father’s staff. Along with his brother, Frederick, he was with his father when he died. He resigned on December 6, 1862. His last residence was in Bloomfield, New Jersey. Section 149, lot 13045.

Civil War Bio Search

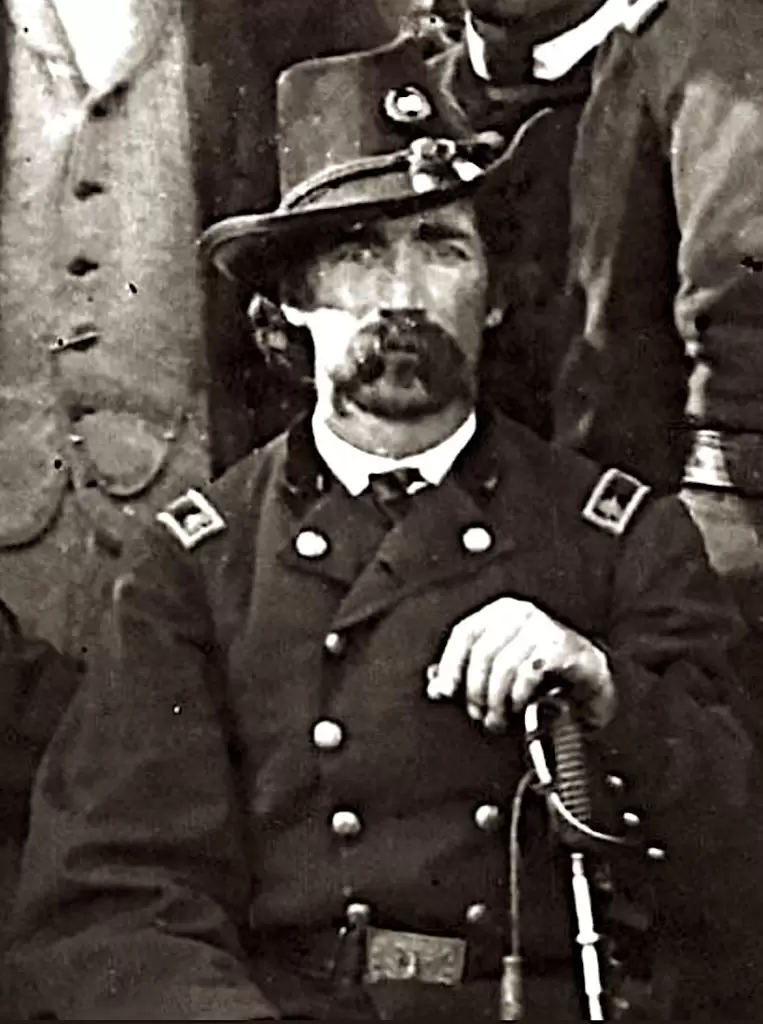

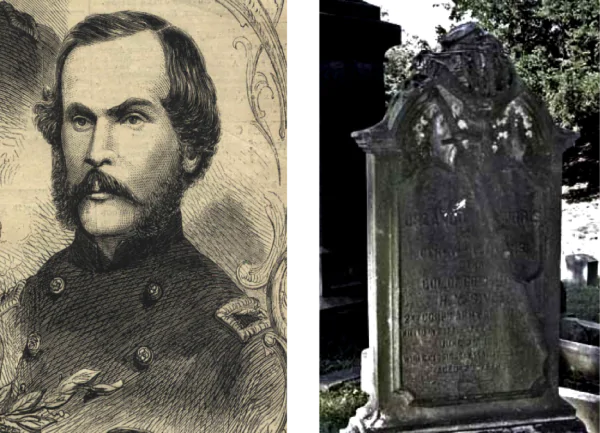

MITCHEL, FREDERICK AUGUSTUS (1839-1918). Captain and aide-de-camp, United States Volunteers; second lieutenant, 21st New York Infantry, Company A; 16th Infantry, United States Army. A native of Cincinnati, Ohio, Mitchel was the son of Ormsby McKnight Mitchel (see) and brother of Edwin William Mitchel (see). As per the Semicentennial Biographical Catalogue of the Zeta Psi Fraternity, he was educated in Cincinnati and then at Brown from 1856-60. During the Civil War, Mitchel enlisted as a second lieutenant on August 27, 1861, at Washington, D.C., was commissioned into the 21st New York that same day and served there until he was discharged for promotion to captain and aide-de-camp of United States Volunteers on September 3, 1862. Serving with his father, he was with him in South Carolina when he died, and left Volunteers when his term expired on November 7 of that year. He was commissioned into the 16th Infantry of the United States Army as a second lieutenant on March 25, 1863, and resigned on August 17, 1863.

In 1881, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 1,072,709. The Zeta Psi biographical sketch and The Reader’s Dictionary of Authors (H. M. Ayres, ed., 1917) indicate that Mitchel was a novelist and biographer. Among his works were an account about his father, Ormsby McKnight Mitchel, Astronomer and General, a Biographical Narrative (1887) and Chattanooga (1891) and Chickamauga (1892), two romances of the American Civil War. Mitchel also wrote magazine articles. One for Lippincott’s titled Confessions of an Aide-de-Camp, was described as a “rattling tale” of the Civil War in which the hero and heroine have surprising adventures. An article in the Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey) on May 29, 1896 (just before Decoration Day), noted that General O. M. Mitchel’s burial place was at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn and that F. A. Mitchel was interested in the care of the grave.

He was living in East Orange, New Jersey, and working as an author at the time of the census of 1900. When he applied for a passport in 1909, he indicated that he pursued the occupation of literature. He was 5′ 4″ tall with brown eyes, a Roman nose, grizzled gray hair, a square forehead, narrow mouth, pointed chin, and small and narrow face. The 1916 Orange, New Jersey City Directory lists Mitchel as a writer. He last lived at 140 Prospect Street in East Orange, New Jersey. His causes of death are listed as endocarditis and arteriosclerosis. Shortly after his death in 1918, Maria G. Mitchel applied for a widow’s pension that was granted under certificate 870,000. Section 149, lot 13045.

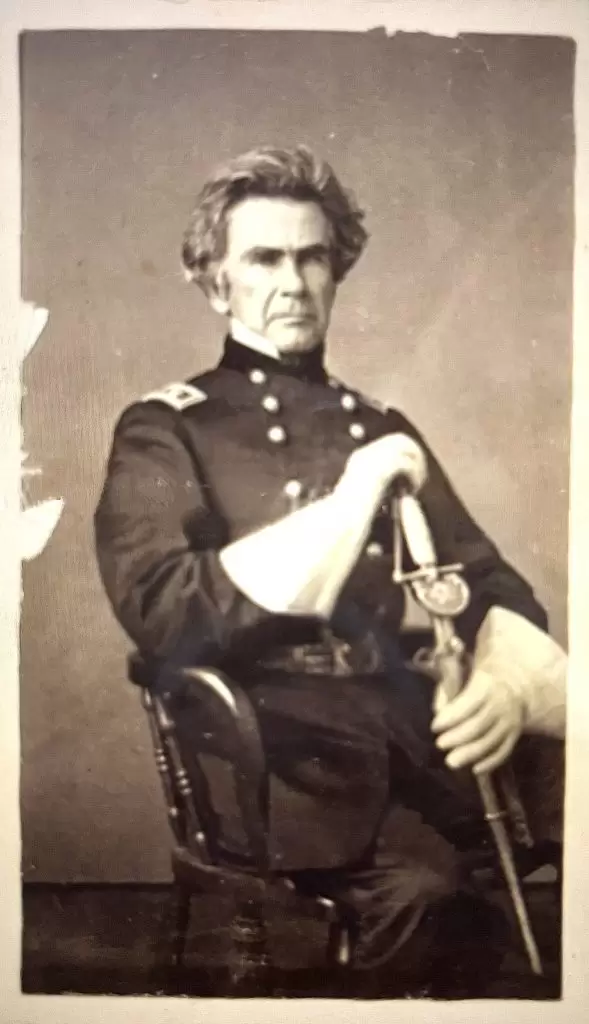

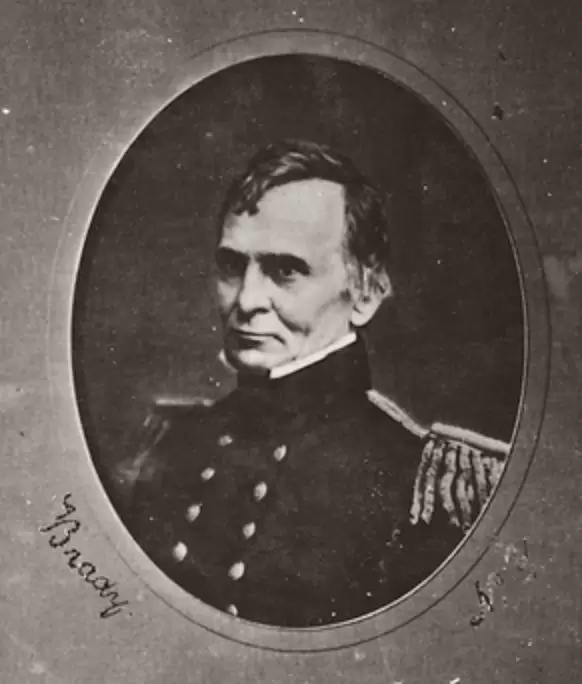

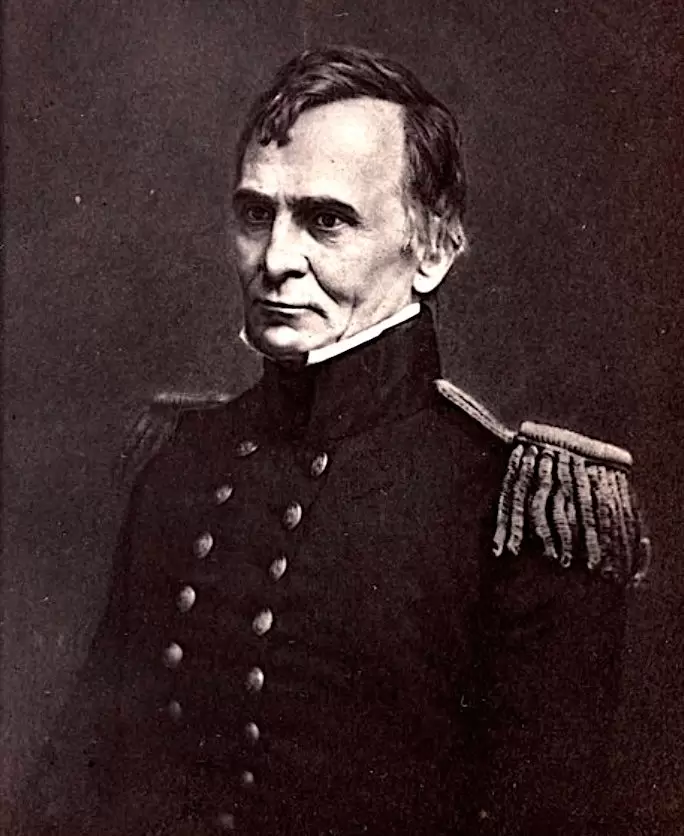

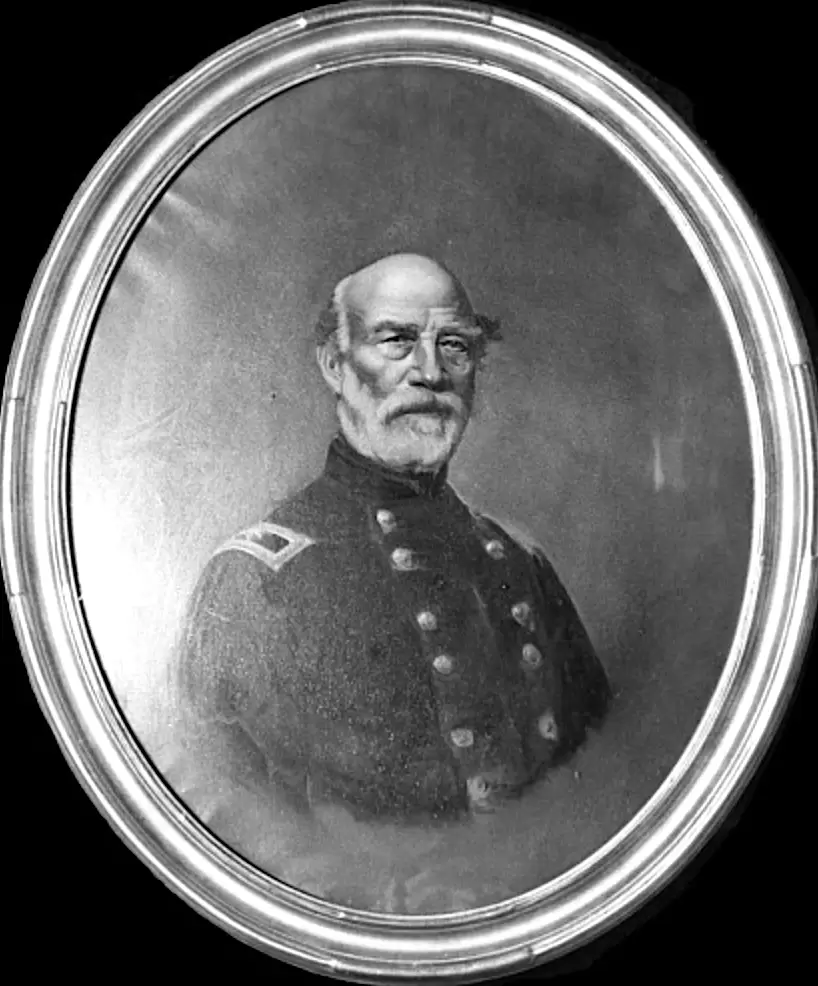

MITCHEL, ORMSBY McKNIGHT (1810-1862). Major general, Department of the South; brigadier general, United States Volunteers; Department and Army of Ohio and Cumberland. Born in Morganfield, Kentucky, his family relocated to Ohio after his father’s death. Mitchel was a 1829 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point (ranking 15 in a class of 46), and served as assistant professor of mathematics there from August 30, 1829, through August 28, 1831. After serving on garrison duty until September 30, 1832, he resigned, was admitted to the bar, practiced law for two years in Cincinnati, Ohio, was chief engineer of the Little Miami Railroad, 1836-37, and professor of mathematics, astronomy and philosophy at Cincinnati College, 1834-44. During his time as a professor, he traveled to Munich, Germany, in 1842 where he procured a 12 inch glass for an equatorial telescope, then studied at the Greenwich Observatory in England before heading back to the United States. A renowned lecturer of astronomy whose personal magnetism helped fuel an interest in his subject to all audiences, he was instrumental in building the refractory telescope in Cincinnati and helped establish the Dudley Observatory in Albany, the Naval Observatory, and the Harvard Observatory. A member of various scientific associations, he wrote Popular Astronomy in 1860.

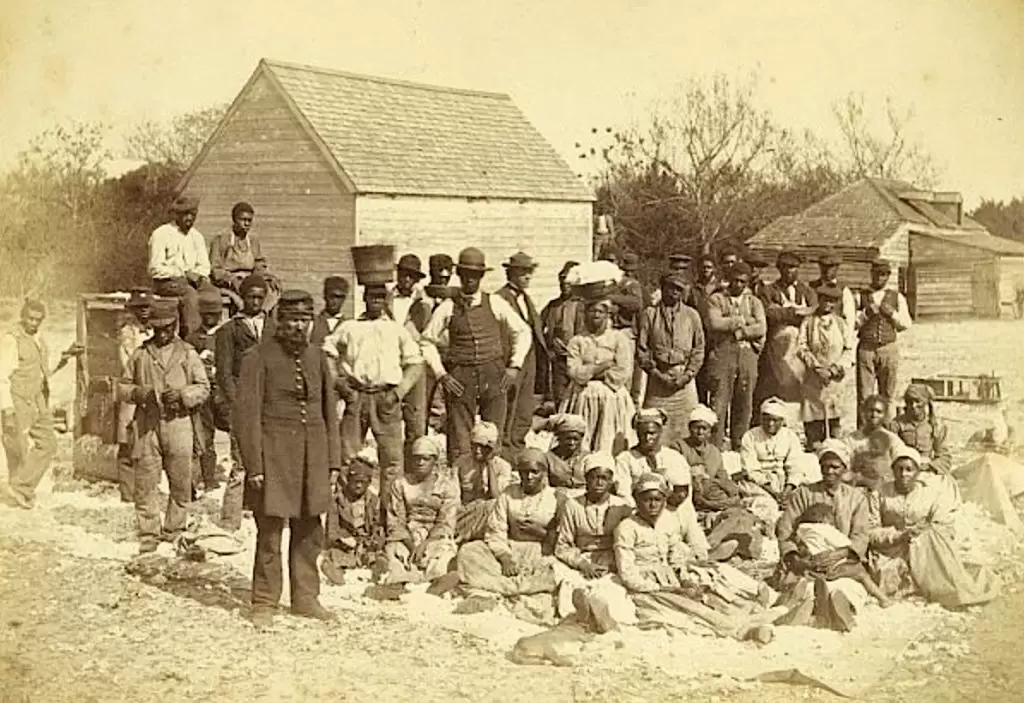

At the start of the Civil War, Mitchel was commissioned brigadier general of United States Volunteers on August 9, 1861, and at first reported to General McClellan, who assigned him the command of General William B. Franklin’s brigade in the Army of the Potomac; but at the request of the citizens of Cincinnati he was transferred to that city and commanded the Department of the Ohio from September 19 to November 13, 1861. He served with the Army of the Ohio during the campaigns of the winter of 1861-62 in Tennessee and northern Alabama. He was engaged in the occupations of Bowling Green, Kentucky, and Nashville, Tennessee, the march to Huntsville, Alabama, the action near Bridgeport, Alabama, April 30, 1862, and was promoted major general of volunteers to date from April 11, 1862. He took possession of the railroad from Decatur to Stephenson, securing the control of northern Alabama to the Federal authorities. Eager to advance into the heart of the South, he was restrained by his superior officer, General Buell. As a result of his dispute with Buell, he tendered his resignation to the secretary of war and was transferred to the command of the Department of the South, headquartered at Hilton Head, South Carolina, as of September 17, 1862. In Hilton Head, the Union had liberated the sea islands and Ormsby gave the order freeing the enslaved people there and providing them with a land for a town and a plot on which they could grow crops.

According to Jack D. Welsh, M.D., in Medical Histories of Union Generals (1996, p. 232), the steamer Delaware, which had docked at Hilton Head on August 26, was quarantined there for ten days because of yellow fever in Key West, Florida, a port visited by the vessel. After members of the 7th New Hampshire, who were on the Delaware, were let ashore at Hilton Head, yellow fever broke out three days later in the camp. Mitchel contracted the disease on October 27, gave up his command, and died three days later at Beaufort, South Carolina. Two of his sons, Edwin William (see) and Frederick Augustus (see) served with him, and a third son, Ormsby McKnight Jr., was a 1865 West Point graduate who served with the 17th Infantry as an adjutant until 1867, then joined the 4th Artillery until 1871. His nickname in the Army, “Old Stars,” was a reference to his fascination with astronomy, an interest that is marked by a star on his gravestone. Originally interred at Beaufort, South Carolina, his remains were moved to Green-Wood on January 16, 1863. The inventor of the declinometer (an instrument for measuring magnetic angles) and other astronomical apparatus, his work, Astronomy of the Bible, was published in 1863, a year after his death. Section 149, lot 13045.

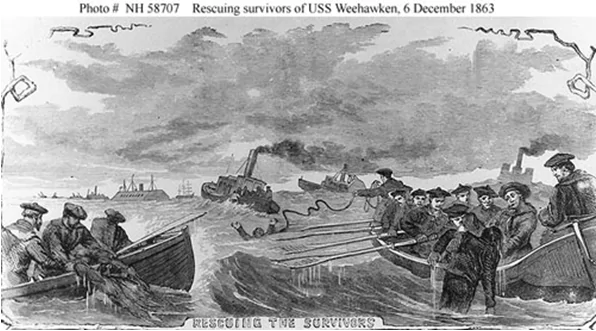

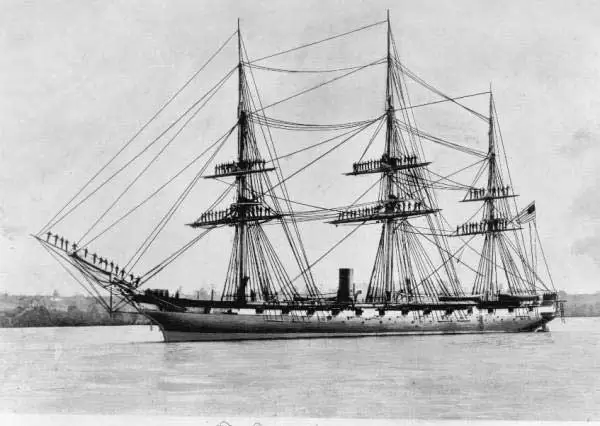

MITCHELL, AUGUSTUS (?-1863). Third assistant engineer, United States Navy. Mitchell first enlisted in the Navy as a third assistant engineer on July 1, 1861, and resigned on May 1, 1862. He re-enlisted as a third assistant engineer on October 6, 1862, and served aboard the USS Weehawken. That vessel, an iron-clad monitor, was commissioned at Jersey City, New Jersey, in mid-January 1863. Serving in Charleston Harbor, near Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 7, 1863, she was struck by over 50 enemy cannons. After repairs, she was in waters off Georgia and on June 17, 1863, and captured the CSS Atlanta and Confederate Major Reid Sanders (see) and Leslie King (see), a second assistant engineer. Returning to Charleston, South Carolina, the Weehawken assisted in the bombardments of Fort Wagner and Fort Sumter. After being grounded on September 7, she was repaired and became part of the blockade off Charleston that October. The Weehawken suddenly sunk in a gale while at anchor off Charleston on December 6. Four engineers who couldn’t escape the flood and 27 other crewmen perished. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on this tragedy on December 12:

…That poor Monitor fleet, which went forth with colors flying, carrying the hopes of the nation with it, has met disaster at every turn, encountered obstacles and sustained repulse, been battered and bruised, and finally settled down at anchorage not far from Morris Island. Even here it has been pursued, and the winds of Heaven with the waves of the ocean have destroyed and pushed down from sight, one of its best and strongest, and most vaunted components.

There was much speculation as to the cause of the Weehawken’s sinking. One admiral attributed it to damage suffered while aground under fire of the Sullivan Island batteries that strained the rivets on its bottom plates. John Ericcson, who pioneered ironclad construction, attributed the sinking to water entering the anchor hoister hatch after it had been accidentally left open by a crew member. Ultimately, the inquiry concluded that a heavy load of ammunition, open hatches and a failure to level the ship after it had taken on water caused the sinking. Although crews attempted to bring up the Weehawken as early as December 1863, it took eight years before the ship and her crew members who perished there were brought back up. The remains of the men were then recovered and given proper burial.

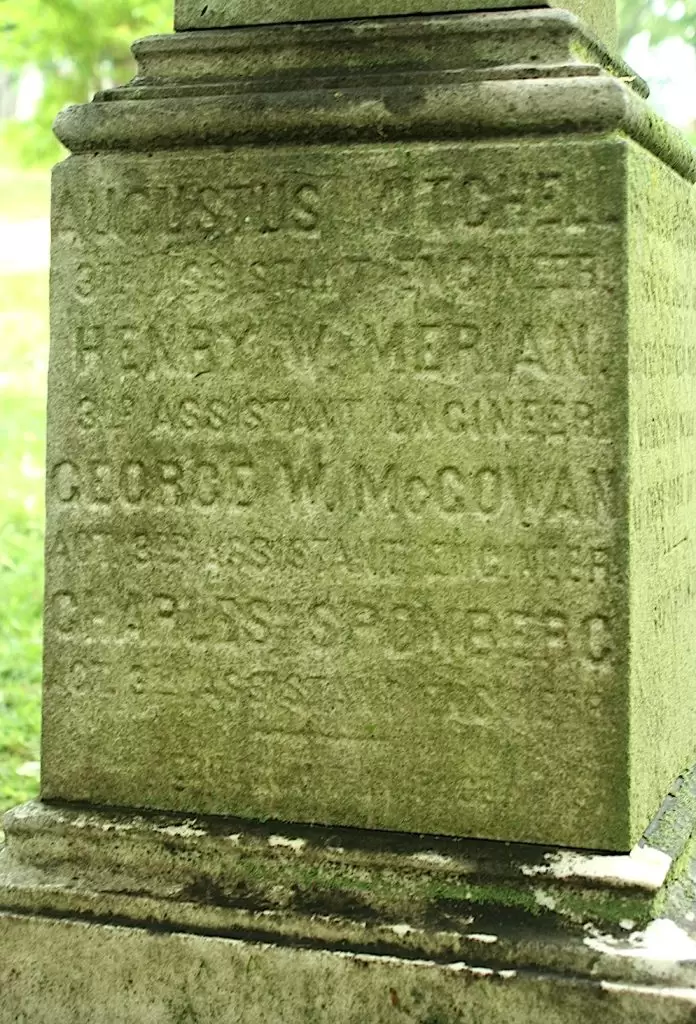

The funeral ceremony was detailed in an article in The New York Times on September 27, 1871. As per that account, the pageant began at the Brooklyn Navy Yard when a small box, containing the bones of the four deceased men, was deposited into a beautiful rosewood casket decorated with silver. A large silver plate which was placed upon the casket read, “This coffin contains the remains of four officers of the United States Navy, attached to the Weehawken, which foundered off Charleston, S.C., Dec. 6, 1863: H. W. MERIDEN (sic), Third Assistant Engineer; AUGUSTUS MITCHELL, Third Assistant Engineer; GEORGE W. MCGOWAN, Acting Third Assistant Engineer; and CHARLES SPONBERG, Acting Third Assistant Engineer.” The funeral procession began at noon with a detachment from the Vermont playing Auld Lang Syne. The cortege was led by the Band, followed by a detachment of Marines, sailors from the Man-of-War, the casket flanked by pall-bearers, a delegation from the Freemasons, and friends and relatives. The detachment of marines fired the customary funeral volleys at the gravesite. The Times noted that rain fell during the cortege and graveside ceremony adding a note of solemnity to the occasion.

Henry W. Merian (see), Augustus Mitchell, George N. McGowan (see), and Charles Sponberg (see) are remembered in a monument at Green-Wood erected in 1871 and dedicated to their valiant efforts. The monument has a carving on its front that states it was erected by Frances Mitchell, who is likely the mother of Augustus Mitchell and who purchased the lot at Green-Wood for the burial of her son and his three comrades, and J. J. Merian, likely the father of Henry Merian. On one side the inscription reads: “SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF FOUR OFFICERS OF THE U.S. NAVY WHO LOST THEIR LIVES BY BEING DROWNED ON THE U.S. MONITOR WEEHAWKEN TO WHICH THEY WERE ATTACHED WHEN SHE FOUNDERED OFF CHARLESTON, S. C. DECEMBER 6, 1863.” The opposite side of the monument is inscribed: , “THE REMAINS WERE EXHUMED FROM THE ENGINE ROOM OF THE WRECKED MONITOR WHERE THEY NOBLY FELL AT THEIR POST OF DUTY. SEPTEMBER 26, 1871. Frances Mitchell, an English-born widow who last lived at 219 East 59th Street in Manhattan, was interred in the same lot as Augustus Mitchell on April 25, 1884. Section 82, lot 20207.

Inscription on the back of memorial: “The remains were exhumed from the Engine Room of the wrecked Monitor where they nobly fell at their post of duty.

MITCHELL, EDWARD LEWIS (1840-1862). Captain by brevet; first lieutenant, 16th Infantry, United States Army, Company F. A New Yorker by birth who resided at 782 Greenwich Avenue in Manhattan, Mitchell, a Columbia Law School student, enlisted as a first lieutenant on May 14, 1861, and was immediately commissioned into the 16th Infantry, United States Army. Captain Edwin F. Townsend of the 16th wrote a few days after the Battle of Shiloh from the battlefield of the heavy fighting on April 7th and Mitchell’s death: he “was instantly killed by a ball through the brain while delivering an order from me…” On April 7, 1862, the same day that Mitchell was killed in action, he was brevetted to captain “for gallantry and meritorious service at the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee.” When he was transported to New York, he was mistakenly listed in the Bodies in Transit database as Edward Lewis. As per his obituary in the New York Daily Tribune, the funeral took place at the home of his father, John F. Mitchell, at 734 Greenwich Street; friends and family and the students and professors of Columbia Law School were invited to attend his funeral. He was interred at Green-Wood on May 5. On May 7, 1862, the New York Daily Tribune published this resolution from his law school classmates:

Whereas, Lieut. Edward L. Mitchell, late a member of the Senior Class in Columbia College Law School, was killed in the battle of Pittsburg Landing,

Resolved, That we respectfully offer to the friends and members of his family our deepest sympathy in their bereavement, trusting that his unselfish life, his strict regard for duty, and his devoted patriotism, may in some slight degree alleviate their sorrow.

Resolved, That the foregoing resolutions be published in the daily papers.

Although his mother, Ann Mitchell, applied for a survivor’s pension on May 9, 1895, application 613,850, it was never certified. Section 25, lot 2980.

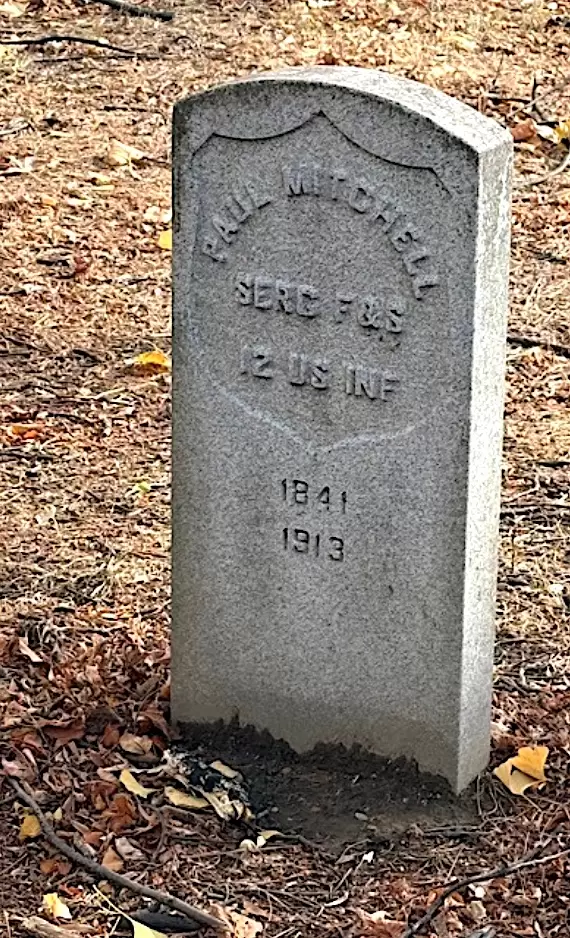

MITCHELL, PAUL (1841-1913). Musician, 12th Infantry, United States Army, Company I; private, 6th Regiment, New York State Militia, Company B. A native of Messina on Sicily in Italy, Mitchell immigrated to the United States in 1845. During the Civil War, he enlisted at New York City as a private on June 20, 1861, mustered into the 6th New York Militia ten days later, and was discharged after three months on October 15 at New York City. On November 29, 1861, Mitchell mustered into Company I of the 12th Infantry, United States Army, as a musician. He served in this unit until the end of the Civil War, was promoted to sergeant on April 4, 1867, and was discharged from military service on December 2, 1867.

In civilian life, he was a musician, composer and teacher. In civilian life, he was a musician, composer and teacher. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which confirms his Civil War service and refers to him as “Professor Mitchell,” reports that he was a member of Gilmore’s, Conterno’s and Sousa’s bands, and was in the Park Theater orchestra during the management of Colonel Sinn. As per the census of 1880, Mitchell was living in Brooklyn and was employed as a music teacher. In 1890, his application for an invalid pension was granted, certificate 828,844. The censuses of 1900 and 1910 indicate that he was a music teacher and that he lived in Brooklyn. He became a member of the Brooklyn Grand Army of the Republic’s Winchester Post #197 in 1907. Among the other organizations to which he belonged were the Brooklyn Italian Mutual Benefit Society of which he had been a president at one time, the Long Island Council of the Royal Arcanum, the Musical Mutual Benefit Association, the Freemasons, and the Brooklyn Masonic Veterans Association. His last residence was 274 Van Buren Street in Brooklyn; he lived in Brooklyn for the last fifty-six years of his life. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that he died after a lingering illness; members of the Brooklyn Masonic Veterans were invited to attend his funeral. Shortly after his death, Sarah Mitchell, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 756,717. Section 164, lot 15771, grave 2.

MITCHELL (or MITCHEL), ROBERT (1839-1913). Private, 14th New York Heavy Artillery, Company A. Originally from Ogdensburgh, New York, he enlisted there as a private on July 24, 1863, and mustered into the 14th Heavy Artillery on August 29. As per his muster roll, he was a painter who was 5′ 5 5/8″ tall with blue eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion. He was discharged on August 28, 1865, at New York City as Robert Mitchel.

The 1880 census lists him (Mitchel with one “l” in surname) as living in Brooklyn and employed as a printer and proofer; Mitchell (with two “ls” in surname) is listed as a printer living at 299 Hewes Street in Lain’s Brooklyn Directories of 1889 and 1897. The 1890 Veterans Schedule confirms Mitchell’s Civil War service. In 1904, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 1,096,619. He became a member of the G.A.R.’s Ulysses S. Grant Post #327 in Brooklyn in 1910. He last resided at 5712 14th Avenue in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to “softening of the brain.” Section 173, lot 15637, grave 1.

MITCHELL, ROBERT (1839-1880). Unknown soldier history. Born in Ireland, the specifics of his military career are unknown. He last resided in Brooklyn. Mitchell succumbed to nephritis. Section 115, lot 13536 (Soldiers’ Lot), grave 80.

MITCHELL, ROLAND GREENE (1841-1906). Private, 7th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company K. Mitchell was born in New York State. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was a descendant of General Nathaniel Greene, who fought in the Revolutionary War, Providence Plantation-founder Roger Williams and Benedict Arnold, the second royal governor of Rhode Island. His great-grandfather, William Minturn, was a partner of Governor Gibbs of Newport, Rhode Island, and his grandfather, Henry Post, founded the shipping firm of Grinnell, Minturn & Company.

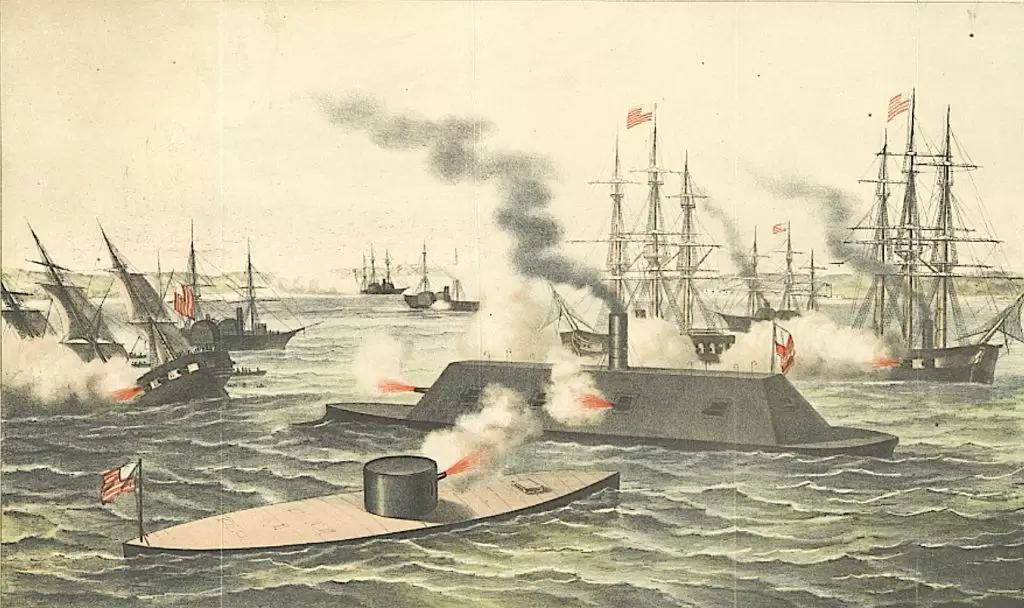

During the Civil War, Mitchell served with the 7th Regiment when it was activated for 30 days in 1863. Letters written by Mitchell appeared in Camp, Battle-Field and Prison by Lydia Minturn Post, published for the United States Sanitary Commission (Bunce & Huntington, Publishers) in 1865. One letter, written from Baltimore on March 11, 1862, describes his impression of the CSS Merrimac; the letter was written two days after the Battle of Hampton Roads. Considering the date of the letter, he may also have served in the 7th Regiment in 1862. He wrote, in part:

…But where is the Merrimac? Directly before us we saw something that looked very much like the peaked roof of a house drifting silently across the bay, and this was the famed craft. Its singular appearance-its still progress- its gloomy blackness, impressed one with a feeling of awe, and one forgot that it was fashioned by hands, and thought it some terrible monster, whose dread power none could foretell.

…With what intense interest we watched the ensuing conflict, you well can imagine.

How at first a belt of fire flashing ‘long the broadside; then dark sulphurous clouds eddied slowly away; and then, so quickly following, the rumbling roar of the explosion would come booming over the water.

How the balls went skipping over the bay, wide of the mark, sending sparkling jets high into the air.

How, when a better range was obtained, shot aimed point blank at the Merrimac, glancing from her sloping side, dashed the water into foam almost a right-angle from the direction in which it was fired.

How, as the firing became more and more rapid, the volume of sound swelled momentarily, until the ground trembled under our feet with the intermingling concussions.

And then how, when the shades of evening gathered round us, the view grew very grand, for at every discharge there issued from the vessel a sheet of flame—a perfect torrent of fire.

Truly it was a gallant sight, once seen never to be forgotten!

As the day wore on, however, the affair became more tragic, and sorrowfully we heard the sinking [USS] Cumberland fire her last shot at the foe, and saw the white flag flutter on the mast of the [USS] Congress.

At last the Merrimac drew off, and delivering a parting shot, moved slowly away.

Thus ended an engagement that has no precedent in history, and from which dates a new era in naval warfare. Long will its stirring scenes live in story and in song.

He wrote from the Baltimore Club-house in July of 1863:

You will, doubtless, be surprised when you see the stamp upon this paper. This morning our company was ordered to “pack up,” and get ourselves in marching order. We were marched into this city to take possession of the Maryland Club-house, which has been seized by the order of General Schenck. So here we are, having full possession of a most splendid house, furnished luxuriously, and situated in the most fashionable part of the town. Our sentries at the front-door sit in splendidly carved chairs, and the rest of us pass in and out at our pleasure. We are having a most enjoyable time, though I think it will be short lived, as we expect to return in a few days.

They have got up a story here, within a few hours, that the expelled members are going to try to retake their club-house, so we have to keep a strong guard. In looking over the visitor’s book, I see numerous names, even as late as the beginning of the week with C.S.A. and C.S.N. opposite, written in full; also the name of the one who introduced them to the club.

I am writing on a large library table, around which we are gathered, some ten or twelve fellows, while the rest are playing billiards in a room adjoining, which contains three fine tables—so you see we have some relaxation to “temper the stern realities of war.”

The census of 1880 indicates that he lived in Great Neck; no occupation is listed. An article in The New York Times on July 5, 1882, reported that his three-story candle factory at First Avenue and 4th Street was destroyed in a major fire. The article said that it is likely that a firecracker, thrown by a mischief-maker, started the conflagration; neighbors were unhappy about the noxious fumes that had emanated from the factory for a decade. Eleven engine companies reported to the scene of the conflagration. It was estimated that 20,000 people watched the scene on the Fourth of July. The article noted that the losses were most likely in the $80,000-$85,000 range; of that, the loss to the property was $25,000. After the fire was put out, there were an estimated 250-350 tons of tallow floating on the water; the estimate of the loss of this salvage was one to three cents per pound. This was the second major fire to the factory; a previous fire had occurred twenty years earlier. The 1883 and 1888 New York City Directories report that he was in the candle business at 141 Water Street; his home was 8 West 19th Street in Manhattan. His died at his country residence, Wildwood, in Great Neck, Long Island. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, he died from pneumonia. His funeral took place at the Church of the Ascension at Fifth Avenue and 10th Street in Manhattan. Section 139, lot 26623.

MITCHILL, JOHN GREENOAK (1840-1911). First lieutenant, 101st New York Infantry, Company D; private, 71st Regiment, New York State Militia, Company A. Mitchill was born in New York City. After serving three months in the 71st Regiment’s State Militia in 1861, he re-enlisted on November 1, 1861, at Hancock, New York, as a first lieutenant, and was commissioned into the 101st New York that same day. He was 5′ 9″ tall with blue eyes. Mitchill saw action in Virginia at the Battles of Oak Grove, White Oak Swamp, Savage’s Station, Glendale and Malvern Hill. He was discharged for disability on September 9, 1862, due to sciatica.

His pension index card, which uses the spelling “Mitchell,” reports that his application for an invalid pension was approved in 1880, certificate 858,694. The 1880 census notes that he was living in Brooklyn and working as a clerk in an oil refinery; the Brooklyn Directory for 1888 lists him as a clerk. He was living in Staten Island at the time of the 1900 and 1910 censuses. His last address was 109 St. Marks Place in Staten Island. An identification disc for Mitchill (below) is included in Identification Discs of Union Soldiers in the Civil War: A Complete Classification Guide and Illustrated History by Larry B. Maier and Joseph W. Stahl (2009). Section 95, lot 2634, grave 3.

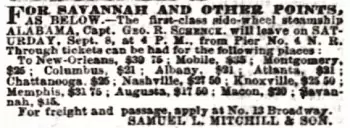

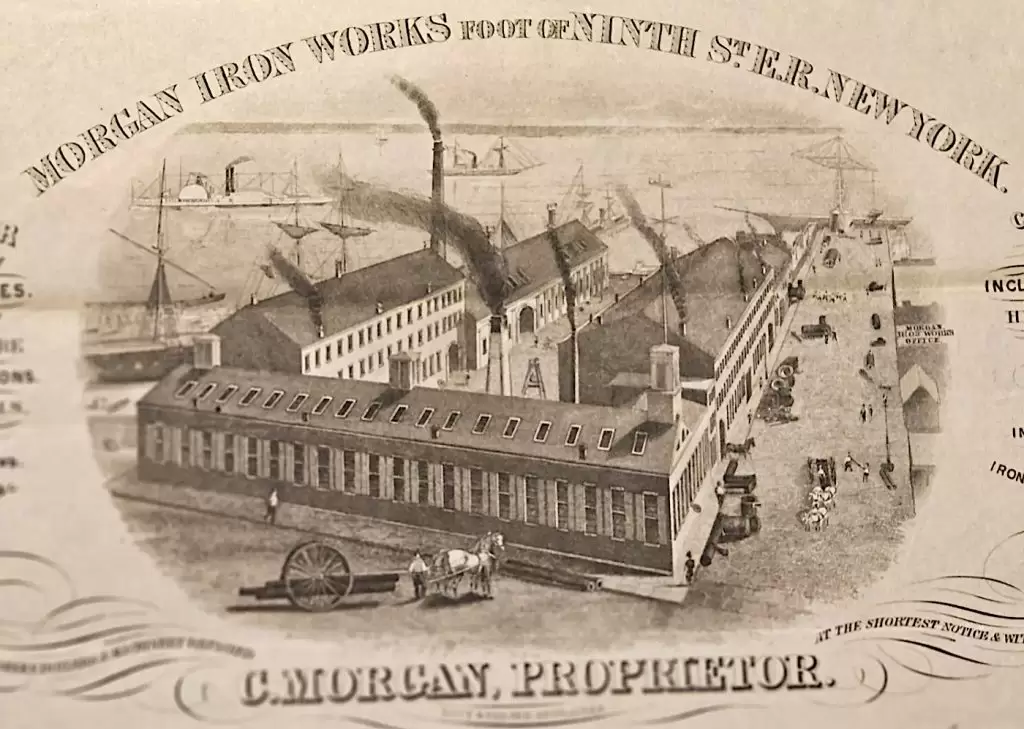

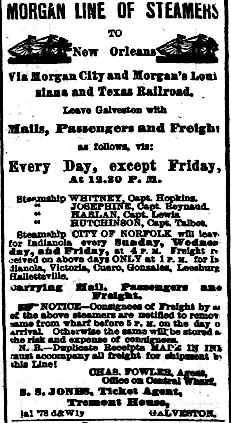

MITCHILL (or MITCHELL), JR., SAMUEL LATHAM (1833-1881). Major, 101st New York Infantry, Company D. A New York City native, Mitchill graduated from Columbia University, class of 1852. A news article about his commencement, which included his name as a recipient of a Bachelor of Arts degree, appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on July 29, 1852. He and his father, who had the same name and is interred in the same lot, owned a side-wheel steamship company. An ad from their company is below.

During the Civil War, he enlisted as a captain at Hancock, New York, on October 27, 1861, and was commissioned into Company D of the 101st New York on that day. As per his muster roll, he was a merchant who was 5′ 10″ tall with gray eyes, black hair and a dark complexion. His muster roll indicates that he was also borne on the rolls as Mitchell. On November 11, 1862, he was promoted to the rank of major and transferred to the Field and Staff. He mustered out the next month on December 24 when his regiment was consolidated. Mitchill’s passport application of January 1863 added further details to his physical description. He noted that he was 5′ 10½” tall with a high forehead, oval face, medium mouth, regular nose and square chin. The 1867 New York City Directory and the 1880 census report that he was a merchant. He last lived at 202 West 34th Street, New York City. The cause of his death was phthisis. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, his funeral was held at the house of his mother at 56 West 56th Street in Manhattan. Section 66, lot 1029.

MITTNACHT, DANIEL (1842-1877). First lieutenant, 62nd New York Infantry, Companies E, C, and F. Born in New York City, he was living there at the time of the census of 1850. During the Civil War, Mittnacht enlisted at New York City as a private on May 15, 1861, mustered into Company E of the 62nd New York on July 3, and transferred to Company C on July 15. As per his muster roll, he was a compositor who was 5′ 7″ tall with gray eyes, dark hair and a fair complexion. On November 2, 1861, he was promoted to corporal of his company and was subsequently promoted to sergeant on October 20, 1862. After re-enlisting on January 1, 1864, he was wounded in action at the Battle of Petersburg, Virginia, on June 18, 1864. He received a promotion to first sergeant on July 10, 1864. On May 17, 1865, he was commissioned as a first lieutenant effective upon his transfer into Company F on June 20. Mittnacht mustered out on August 30, 1865, at Fort Schuyler, New York Harbor.

He is listed as a printer on the census of 1870. In 1876, his application for an invalid pension was approved under certificate 143,971. Mittnacht’s last residence was 85 Varick Street, Manhattan. He succumbed to consumption. In 1882, John Fincken, guardian, applied for a pension for a minor, application 290,581, but it was not certified.

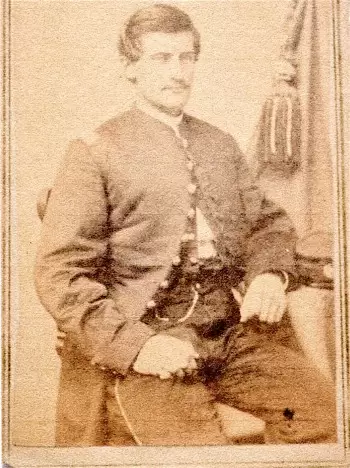

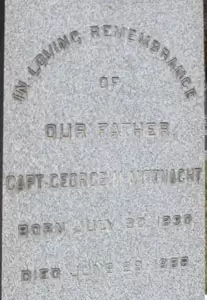

MITTNACHT, GEORGE M. (1830-1889). Captain, 6th Regiment, New York State Militia, Company E; 103rd New York Infantry, Company H. Born in Bavaria, Germany, Mittnacht immigrated to the United States in 1849. His obituary in his local newspaper, the Newtown Register, indicates that he arrived in this country in the same period as other German political refugees including Generals Franz Sigel and Carl Schurz. That obituary also reports that Mittnacht joined the 11th Regiment, New York State Militia, in 1855.

During the Civil War, he served with both the 6th and 103rd Regiments. He was commissioned into the 6th Regiment as a captain on April 19, 1861, and mustered out after three months on July 31, 1861. He then re-enlisted on February 19, 1862, was commissioned into the 103rd New York, also known as the Seward Infantry, and was discharged on June 30, 1862. He returned to the 6th on June 22, 1863, when it was part of the New York State National Guard, was commissioned into Company E, and mustered out after 30 days on July 22, 1863.

In civilian life, Mittnacht was in the safe and iron business on Spring Street in Manhattan; he remained active in the business for forty years. He is listed as a safe manufacturer at the time of the census of 1870 at which time he lived in New York City; the 1874 New York City Directory also lists him in the safe business. The 1880 census and the 1888 New York City Directory note that he was a resident of Long Island City and was a safe manufacturer. An article in The New York Times on March 31, 1882, describes a failed attempt by burglars to open a safe in Mittnacht’s factory at 24 Spring Street. Hook & Ladder Co. #9 was called to the scene because of smoke emanating from a smoldering pile of wood near the safes. When the police questioned Mittnacht, he refused to give any information about the break-in. The motive for the fire, which had been quickly extinguished, was never determined. A Letter to the Editor written by George M. Mittnacht, which he signed as late captain of Company H, was published in The New York Times on December 2, 1883, to correct and clarify the history of the 103rd New York Regiment. The major part of his letter follows:

The statement in your issue of Nov. 25 about the Colonel of the One Hundred and Third New York Volunteers is an error. We never had Charles Miller or A. J. B. Miller (who appears on the roll of the One Hundred and Third as a sergeant) as a Colonel. The regiment was raised after the expiration of the time of service of the Sixth Regiment, New York State Militia, about the latter part of 1861, from officers and men of the Sixth Regiment—namely Capt. C. Schneider, George M. Mittnacht…

The regiment, or rather a part of it, re-enlisted during the war, under Capt. William Redlich and was mustered out in 1865. While under Capt. Redlich’s command the regiment never was up to the requisite number to grant Capt. Redlich a promotion. Capt. Redlich was Sergeant of Company H (my company) when the regiment left New York. It was owing to his good deeds and name that the remnant of the regiment was not consolidated with other regiments and we have to thank him that the regiment was brought home with its original name—Seward Infantry, One hundred and Third New York Volunteers—of which we have all reason to be proud.

His last residence was 57 Camelia Street in Astoria, New York. The cause of his death was Bright’s disease. As per Mittnacht’s obituary in the New York Herald, which confirms his Civil War service, news of his death was sent to Maryland newspapers; his wife Mary, who is interred with him, was born Maryland. His gravestone is inscribed with his service as captain. Section 163, lot 14715, graves 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14.

MIX, EUGENE (1841-1910). Private, 7th Regiment, New York State Militia, Company B. Mix, who was born in New York, served for 30 days in 1861 with the 7th Regiment. The census of 1880 indicates that he was living in Newark, New Jersey, and employed as a railroad clerk; the 1900 census notes that he was still living in Newark and was working as a railroad baggage master. In 1905, his pension application was approved, certificate 1,113,531. According to his obituary in the New York Herald, he was a member of the 7th Regiment Veteran Association; members of the organization were invited to attend his funeral. Mix was not working at the time of the 1910 census. He last lived at 69 Wright Street in Newark, New Jersey. He died from nephritis. Sarah Mix applied for and received a widow’s pension after his death in 1910, certificate 715,790. Section 119, lot 7437.

MOAT, LOUIS S. (1841-1902). Commissary sergeant, 1st New York Engineers, Companies F and L. As per his online family tree on Ancestry.com, Louis was born in New York to parents Horatio Shepherd Moat and Martha Maria née Troke. He lived in New York City at the time of 1855 New York State census and in Brooklyn in 1860. The 1860 census details that Louis lived with his parents in Brooklyn and was employed as a clerk. Also in the household were older sisters Martha (age 23), Harriett (age 20), and younger brother Benjamin (age 12).

During the Civil war, Louis enlisted as a private at Brooklyn on December 23, 1861 and mustered immediately into Company F of the 1st New York Engineers. Louis was described on the muster roll as being 5′ 9½” tall with grey eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion. His occupation was listed as soldier. His muster roll details that he re-enlisted on March 1, 1864 (listed as February 29 on another source) and that he transferred that day into Company L. Subsequently, he transferred into the Field and Staff on January 7, 1865, with the rank of commissary sergeant. At some point he was an artificer before the aforementioned transfer. He mustered out on June 30, 1865, with non-commissioned staff on June 30, 1865, at Richmond, Virginia. As per the 1890 Veterans Census, Louis served two years, one month and 11 days.

As per the 1865 New York State census, Louis was living at home with his parents, older sisters and younger brother. Four boarders were named as being part of the household.

He married Virginia Smith on November 25, 1867, in Brooklyn. As per the online family tree, the couple had three children, two of whom died young: Horatio (Harry) (1868-1877); Louis Sheppard (1872-1922); and Frank (1879-1880). According to the 1875 New York State census, Louis and Virginia lived in Brooklyn with their two sons, Horatio, age 6, and Louis, age 2. The Moats lived at 176 Duffield Street at the time of the 1880 census. That census shows Louis, age 7, and Frank, age 1, as members of the household. Louis, the father, was then employed as a bookkeeper.

Although Moat applied for an invalid pension in 1893, application 1,114,178, no certificate number is listed. The 1900 census reports that he lived at 78 St. Marks Avenue with his wife and a 34-year-old servant named Maggie Jeffers. Louis rented his home, had been married for 33 years, and could read and write. The Veterans Census of 1890 confirms his service during the Civil War and lists his rank as commissary sergeant. The 1902 Brooklyn Directory records Louis Moat as a bookkeeper.

His death certificate notes his death at age 60 in New York City. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Louis died suddenly. Cemetery records attribute his death to apoplexy. His funeral took place at his residence on St. Marks Avenue. Shortly after his death in 1902, Virginia Moat applied for and was awarded a widow’s pension, certificate 550,692. Section 180, lot 15116, grave 3.

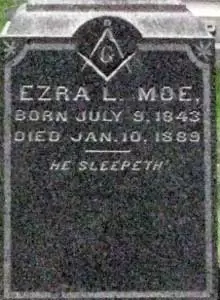

MOE, EZRA L. (1843-1889). Private, 120th New York Infantry, Company A; 19th Regiment, Veteran Reserve Corps, Company F. Moe was born in Greene County, New York. The 1860 census reports that he was living in Hurley, New York, and working as a laborer. After Moe enlisted as a private on August 6, 1862, at Hurley, New York, he mustered into the 120th New York, also known as the Washington Guards, on August 22. His muster roll notes that he was a farmer who was 5′ 6″ tall with gray eyes, dark hair and a light complexion.

The 120th New York saw action in nearly every major battle after Fredericksburg in December 1862, and was on duty when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865. Just before its final engagements in March 1865, the regiment received a new flag which was inscribed with the names of the 16 battles in which it had fought. Moe’s muster roll also reports that he was absent and sick as of May 10, 1864, hadn’t been heard from in six months, and was discharged on April 28, 1865, as per General Order #77. In June 1865, the regiment was welcomed home at Rondout, New York, with a lavish reception. Rev. Henry Hopkins, the 120th Regiment’s chaplain, said, “We were crowned with flowers, every soldier had a bouquet in the muzzle of his gun.” On June 3, 1865, Moe transferred into Company F of the 19th Regiment, Veteran Reserve Corps. He was discharged from military service on November 15, 1865, at Elmira, New York.

The 1870 census notes that he was a farm laborer living in Tioga, New York. Moe is listed as a carman in the 1884 Brooklyn Directory. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, friends and relatives were invited to attend his funeral. He last lived at 197 Nassau Street in Brooklyn. He died from pneumonia. In 1890, Adelia Moe for a widow’s pension, application 468,986, but no certificate number is listed. Section 200, lot 26862.

MOESLEIN (or MOSHIER), SEBASTIAN (1832-1901). Sergeant, 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, Company H; musician, 41st New York Infantry; United States Volunteers Brigade Band. Originally from Bavaria, Germany, Moeslein enlisted as a musician at New York City on June 26, 1861, mustered into the Band of the 41st New York that same day, and was discharged on June 30, 1862, at Middletown, Virginia. A resident of Fairfield, Connecticut, he then re-enlisted as a private and mustered into Company H of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery on November 4, 1862. He was promoted to sergeant on November 4, 1862, and was transferred to the United States Volunteers Brigade Band on March 26, 1863. In 1891, he successfully applied for an invalid pension, certificate 975,570. He last resided in New York City. Interment at Green-Wood took place on May 23, 1903. Section 206, lot 21347, grave 615.

MOFFETT (or MOFFITT), STEWART R. (1844-1892). Private, 3rd New Jersey Infantry, Company B; 12th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company I. A New Jersey native, Moffett lived with his parents and siblings in Rahway, New Jersey, at the time of the census of 1860. After enlisting as a private on April 22, 1822, Moffett mustered into the 3rd New Jersey Infantry on April 27, and mustered out on July 31, 1861, at Trenton, New Jersey. As per his pension index, he last served in Company I of the 12th New York Regiment and had additional service in Company B of the 9th New Jersey Infantry; there are no additional details about those enlistments.

The City Directory for Newark, New Jersey, lists him as a photographer with Logan & Moffett at 299 Broad Street in 1865; his company had a gross income of $4,679 in 1867. The 1870 census indicates that Moffett was living in Newark and employed in a photograph gallery; he is also listed as a photographer in the Newark Directory for 1870 and in the 1880 census. Moffett relocated to New York City where he is listed in the 1884 New York City Directory; he lived at 174 Sixth Avenue and continued his profession as a photographer. He last lived at 432 7th Street in Brooklyn. His death was caused by an aortic aneurysm. Shortly after his death in 1892, Anna Moffett applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 367,638. Section 77, lot 8354.

MOGK, WILLIAM JACOB (or JACOB W.) (1836-1915). Unknown rank, 1st United States Artillery, Battery M; private, 15th New York Heavy Artillery, Company E. Originally from Germany, Mogk immigrated to the United States in 1862. He used the name Jacob Mogk on his soldier and census records. As per his pension index card, Mogk served in the 1st United States Artillery, Battery M; details of that service are unknown. He re- enlisted as a private at New York City on February 3, 1864, and mustered into the 15th New York Heavy Artillery that same day. As per his muster roll, he was a sign maker who was 5′ 5″ tall with gray eyes, light hair and a light complexion. Mogk mustered out with his company on August 22, 1865, at Washington, D.C.

In 1897, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 937,852. As per the census of 1910, he was a widower who was a naturalized citizen, was able to read and write and was a survivor of the Union Army; he then lived on 20th Street in Brooklyn as a boarder. He last lived at 83 20th Street in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to bronchitis. Section 131, lot 34213.

MOHR, HENRY (1841-1881). Corporal, 54th New York Infantry, Companies B and C. Born in Hessen, Germany, Mohr enlisted on September 5, 1861, at Hudson City, New Jersey, as a private, and mustered into Company B of the 54th New York Infantry that same day. At some point, he had an intra-regimental transfer to Company C. Although his soldier record reports that he deserted at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on June 20, 1863, that appears to be incorrect; on December 11, 1874, he mustered into Frank Head Post #16 of the G.A.R., an organization of Civil War veterans that did not consider deserters for membership. Mohr indicated in the G.A.R. sketchbook that he was discharged as a corporal from the 54th on September 15, 1864.

Mohr was listed as a saloonkeeper in the Brooklyn Directories for 1868 and 1870, and in the G.A.R. sketchbook. An article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on August 2, 1872, lists Mohr as one of saloonkeepers who met and organized to resist the enforcement of the excise tax law. He was working as a saloonkeeper at the time of the 1880 census; he was living in Brooklyn with his wife and seven children. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle of January 16, 1881, noted that Mohr was elected as delegate to the State Encampment from Frank Head Post of the G.A.R. His last residence was 54 Rapelyea Street, Brooklyn, New York. His death was attributed to enlargement of the liver. As per his wife’s petition to King’s County Surrogate Court, he died without a will and had personal property worth $400. Eliza Mohr, his widow, took over his lager beer saloon at the Rapelyea Street address. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle on November 21, 1881, reported that the saloon was broken into and that three bottles of whisky and fifty cigars were stolen. Section 122, lot 17806, grave 236.

MOLLER, CHARLES A. (1834-1888). Private, 72nd New York Infantry, Company A; 73rd New York Infantry. Of German origin, Moller enlisted as a private at New York City on June 3, 1861, and mustered into Company A of the 72nd New York on June 21. On July 23, 1861, he was transferred into the 73rd New York. He died in Brooklyn but last lived at 234 Hudson Street in Hoboken, New Jersey. The cause of his death was senile gangrene (insufficient blood flow caused by degeneration of the walls of the arteries). Section 83, lot 3349.

MOLLOY, ALFRED C. (1843-1889). Landsman, United States Navy. Of Irish origin, Molloy enlisted as a landsman in the United States Navy at New York City on August 8, 1863, for a term of one year. At that time, he was an upholsterer who was 5′ 10½” tall with grey eyes, brown hair and a light complexion. It was noted that he had scars on his right arm and right cheek. Molloy served on the USS Quaker City as of August 14. He was admitted to the Naval Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on October 3, 1863, suffering from vulnus contusum (crush wounds). He was discharged from the hospital on November 4. He subsequently served on the USS Princess Royal as of June 16, 1864, and was discharged on October 29, 1864.

On May 26, 1873, Molloy became a naturalized citizen; at that time, he was a clerk who lived at 1 Christopher Street in New York City. His death certificate notes that he had been employed as a clerk and that he died in Kearny, New Jersey. As of July 1890, Hannah Molloy, whom he married in 1870, received a widow’s pension, certificate 5,438, of $8 per month and an additional $2 per month for each of her two minor children.

MOLLOY, JOHN COOK (1829-1873). First lieutenant, 63rd New York Infantry, Company B. Of Irish birth, he enlisted and was commissioned into the 63rd New York at Washington, D.C., on December 7, 1861, and mustered out on February 13, 1862. He last lived in Hoboken, New Jersey. Section 116, lot 11522.

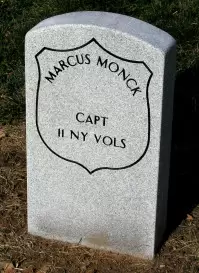

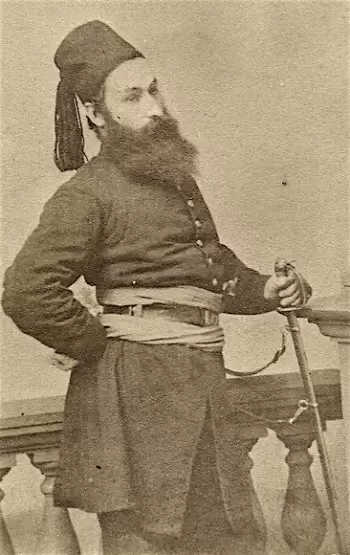

MONCK, MARCUS (1832-1862). Captain, 11th New York Volunteers. Although Monck’s naturalization papers state he was of English origin, his muster roll, family tree and death certificate indicate that his birthplace was in Banagher, Ireland. The New York City Directory for 1854 lists him as an editor for M. B. Monck & Co., publishers at 216 Pearl Street; the 1857 New York City Directory lists him as a publisher whose office was at 71 Nassau Street in Manhattan; he lived on Henry Street in Brooklyn. After filing a petition for naturalization at the Court of Common Pleas in New York City on September 17, 1855, Monck became a naturalized citizen on September 3, 1859.

During the Civil War, it appears that Monck served with the 11th Regiment-the First Fire Zouaves. His muster roll states that he was borne on the Inspection Roll in Company B of Scott’s Rifles, dated August 27, 1861, and had no service as captain in the 51st Infantry (the regiment formed by consolidation of Scott, Union and Shepard Rifles on October 11, 1861). The records of the New York State Adjutant General’s Office confirm that Monck was in Company B of Scott’s Rifles from August 27, 1861, through October 11, 1861 and New York Veteran Burial Cards state that he was a captain in the 11th Regiment, New York Volunteers.

The 1862 New York City Directory reports that Monck was an editor at 19 Beekman Street and lived in Brooklyn. An article in The New York Times on August 13, 1862, reports that Captain Munck was severely burned on August 6, 1862 in the fire at the Rainbow Hotel on the corner of William and Beekman Streets in Manhattan. He died at the New-York Hospital five days later. An inquest into his death by Coroner Wildey (see) concluded that his death was caused by accidental burns. His funeral was held at City Hospital and his remains were accompanied for burial by two companies of the Stanton Legion. The photograph of Monck (below) notes that lost his life trying to save people in a burning house in New York. Section 115, lot 13536 (Soldiers’ Lot), grave 33.

MONCRIEFF, GEORGE S. (1814-1869). Quartermaster sergeant, 5th Light Artillery, United States Army; sergeant, 3rd Infantry, United States Army, Companies I and F. A native of Scotland, he served as a sergeant in Companies I and F of the 3rd Infantry, U.S. Army. Subsequently, he re-enlisted as a quartermaster sergeant and served with the 5th Light Artillery, U.S. Army. There is no further information about his military record. His last address was in New York City and his death was caused by kidney disease. Section D, lot 7078, grave 55.

MONEYPENNY (or MONTGOMERY), WILLIAM C. (1832-1878). First lieutenant, 14th New York Cavalry, Company C; 8th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company D. A New Yorker by birth, Moneypenny was listed as living in New York City and working as a dyer in the census of 1850. During the Civil War, he enlisted at New York City on May 29, 1862, mustered into the 8th Regiment that day, and mustered out with his company after three months on September 10 at New York City. He then re-enlisted at New York City as a first lieutenant on December 12, 1862, was immediately commissioned into the 14th New York Cavalry, and was discharged on July 13, 1863. His muster roll for the 14th Cavalry notes that he was also known as William Montgomery.

The New York City Directories for 1870 and 1875 list him as a dyer. He last lived on State Street in Albany, New York. His obituary in The Albany Daily Evening Times of October 30, 1878, reported that his remains were taken to New York for interment. Eliza Moneypenny applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1892, certificate 362,610. Section 161, lot 12578.

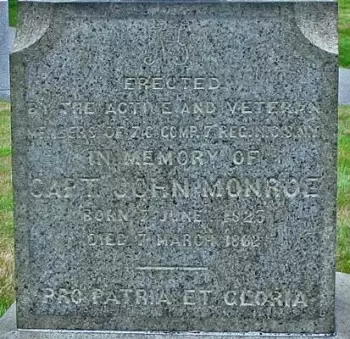

MONROE, JOHN (1823-1862). Captain, 7th Regiment, New York State Militia, Company G. As per a biography about Monroe written in 1858, he was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and came to New York City when he was two years old. His military interests started early when he became a guide boy for the Third Company National Guard when he was just nine years old. In 1843, he joined the Seventh National Guard becoming a first lieutenant on August 15, 1850, and was elected captain on March 13, 1851. When he was elected captain, his company had only eighteen men but it soon numbered nearly one hundred due to his perseverance and the respect in which his command held him. In civilian life, he was a bookkeeper.

During the Civil War, Monroe enlisted as a captain at New York City in April 1861, was commissioned into the 7th Regiment, served for 30 days and mustered out at New York City on June 3. Known as a tactician, he compiled “Manual of Arms” which was introduced at Camp Cameron in 1861. As per his obituary in the New York Tribune, his funeral was held at the New-England Church on South 9th Street in Brooklyn; members of the 7th Regiment were invited to attend in civilian dress. After his death, members of the 7th adopted resolutions of condolence and wrote, “He was an able, reliable, laborious, and intelligent officer…Of rather an unsoldierly figure, and without the personal attractions which sometime win favor, Captain Monroe achieved distinction by modest merit, and ranked high among the distinguished company commandments of the period.” An impressive monument in his honor was erected by the active and veteran members of Company A of the 7th Regiment and bears the Latin inscription, Pro Patria Et Gloria (For Country and Glory). Section 55, lot 6388.

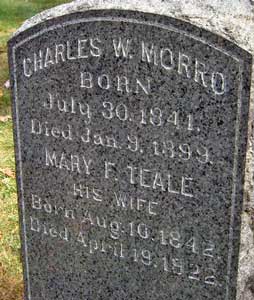

MONROE (or MUNRO), ROBERT (1831 or 1842-1922). Private, 9th New York Infantry, Company K. Monroe, or Munro, as his named is spelled on many records, was born in Scotland as per the New York State census of 1892. The year of Monroe’s birth is uncertain; although the inscription on his gravestone indicates that he died at 91 years of age, that information may not be correct. Other records indicate his birth year as 1841 or 1842. He immigrated to the United States in the 1850s; the 1910 census reports the year as 1854 whereas the 1920 census records the year as 1858.

During the Civil War, he enlisted as a private at New York City on May 3, 1861, and mustered into Company K of the 9th New York, also known as Hawkins’ Zouaves, the next day. Company K was equipped as an artillery unit. The regiment, composed of mainly New Yorkers, headed for Fortress Monroe, Virginia, on June 6, and was then quartered at Newport News, Virginia, where Monroe was discharged for disability on August 14, 1861.

He became a naturalized citizen in 1864. The 1877 and 1885 Brooklyn Directories list Robert Munro as a machinist whose home was on 41st Street and Seventh Avenue. In 1888, he applied for and received an invalid pension, using the surname of Munro, certificate 851,805. The Brooklyn Directory for 1897, using the spelling “Monroe,” lists him as a machinist at 363 41st Street. At the time of the 1905 New York State census, he was a machinist living with his daughter and son at 665 41st Street in Brooklyn. As per the census of 1910, he was still living at 665 41st Street, working as a machinist in a factory, and living with his daughter. The 1920 census indicates that he was widowed and no longer employed. According to papers filed in Kings County Surrogate Court by his daughter, the executrix of his will, on July 18, 1922, he left real estate valued at about $6,000 (about $85,000 in 2016 money) and personal property valued at about $50. His daughter, Elizabeth, was still living at the same address on 41st Street at the time of the 1940 census. Section 3, lot 21025.

MONTEITH, WILLIAM (1827-1869). Colonel, 28th Massachusetts Infantry; second lieutenant, 12th Regiment, New York State Militia, Company C. Born in Ireland, Monteith was a hatter according to the 1850 census and a builder as per the 1855 New York State census and the 1857 New York City Directory. He entered service with the 12th Regiment on April 19, 1861, and mustered out on August 5, 1861.

He then was appointed colonel of the 28th Massachusetts on October 7, 1861. The 28th had been raised as the second Irish regiment, building on the large Irish population in Massachusetts and was known familiarly as the Faugh-A-Ballaugh (clear the way) Regiment. Among the patrons of the 28th was Patrick Donahue, the owner of The Pilot, a major Irish-American Catholic newspaper and a friend of Montieth, who despite unknown military ability, was able to secure the commission as colonel from Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrews because of his connection to Donahue. Among others who sought to raise men for the Irish regiments was the Irish nationalist, Thomas Meagher (see), who used his oratorical skills to whip the crowd into a frenzy; Meagher did not receive a commission in Massachusetts but ultimately was acting major of the 69th New York and rose to command of the Irish Brigade—which included the 28th.

As per the 28th Massachusetts Regimental History for 1862 Colonel Monteith and his men received their first two flags after training at Camp Cameron that January in an emotional ceremony led by Governor Andrew, the Boston mayor, and members of the Boston City Council. Eight days later, Monteith chose to forego the third standard state flag for a flag that featured patriotic and Irish symbols on a field of green. The Regimental History went on to say that the 28th performed well despite feuding between Colonel Monteith’s Irish New Yorkers and the locals from Boston. The 28th left for Hilton Head, South Carolina, on February 14, 1862, from Fort Columbus in New York Harbor. One of Monteith’s men, John J. MacDonald, a sergeant in Company K, wrote to The Pilot that while the Regiment lacked a chaplain, they were well cared for, had good sanitary facilities, and had become well-disciplined. In addition, MacDonald wrote about the “Monteith Literary and Aid Society,” an association of which Monteith was the patron. The objective was the well-being of the families of the soldiers. Each month, the members of the association were assessed an unstated amount for the widow and family of members who lost their lives in the discharge of their duty; it also provided for the forwarding of the remains of the deceased to their family or friends, rare benefits at the time.

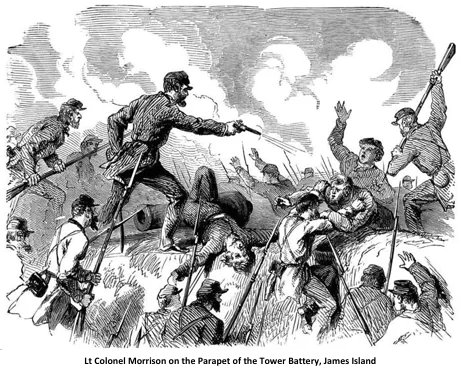

Once the 28th arrived in South Carolina, it was then assigned to General T. W. Sherman’s expeditionary corps until June 1 when it was at James Island for the attack on Fort Johnson near Secessionville. However, on May 20, Montieth was dismissed for “neglect of duty” and “conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman-drinking in his tent with privates of the 76th Pennsylvania regiment.” After he submitted his resignation on August 3, 1862, he was court-martialed at Newport News, Virginia, and was discharged from the Army on August 12.

After the Civil War, he was a hatter. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, which confirms his Civil War service as colonel of the 28th Massachusetts, he died from disease contracted in South Carolina; friends and relatives were invited to attend his funeral. He last lived at 215 West 24th Street in New York City. In 1870, Eunice Monteith applied for a widow’s pension, application 184,939, but there is no evidence that it was certified. Section 33, lot 4800.

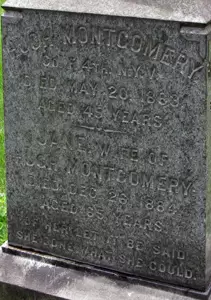

MONTGOMERY, HUGH (1818-1863). Private, 4th New York Infantry, Company F. An Irish native, the 1855 census reports that Montgomery was a grocer; Smith’s Brooklyn Directory for 1856 lists him as a grocer who lived and worked at 13 James Street. After enlisting as a private at New York City on April 22, 1861, Montgomery mustered into Company F of the 4th New York, also known as the First Scott Life Guard, on May 2. His muster roll indicates that he was absent without leave for eighty-two days from December 20, 1862 through March 12, 1863, and returned to duty under the President’s Proclamation of March 13, 1863. As per the aforementioned proclamation, soldiers who were absent without leave were allowed to return to their regiments without punishment by April 1 of that year; soldiers who returned would not be subject to arrest but would lose their pay and any allowances during the period they were away from their unit. He died of disease in New York City on May 20, 1863, just a few days before the regiment mustered out there.

As per his obituary in the New York Herald, which confirms his service in the Civil War, he was a member of the American Protestant Association, an organization comprised mainly of Irish Protestants; members were invited to attend his funeral. Newspapers in Belfast, Ireland, were forwarded information about his death. Montgomery’s funeral was at the home of his brother at 338 Greenwich Street in Manhattan. On July 2, 1863, Jane Montgomery, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 207,364. Section 177, lot 13872.

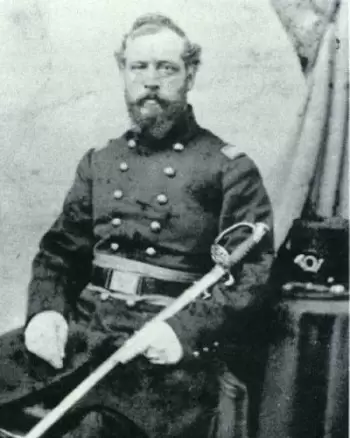

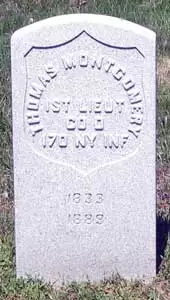

MONTGOMERY, THOMAS (1833-1889). First lieutenant, 170th New York Infantry, Company D. Born in Ireland, Montgomery first served in Company A of the 69th Regiment in 1861. His name was listed in “News of the Rebellion” in The New York Times on July 25, 1861, as among the wounded on July 23 at the Battle of Bull Run, the first major battle of the Civil War. Captain James Kelly wrote about the battle in his report to Headquarters on July 24:

Sir: I have the honor, in the absence of Col. Corcoran, missing, and Acting Lieut.-Col. Haggerty, killed in action, to report to you that on Sunday morning, July 21, at 3:30 a.m., under orders of Maj.c. Gen. McDowell, and the immediate command of Brig.-Gen. Tyler, the Sixty-ninth Regiment New York State Militia moved forward from their camp at Centreville, and proceeded by steady march to within a mile and a half of the enemy’s battery, situated on the south bank of the creek or ravine known as Bull Run. At this point we halted, Col. Corcoran commanding, Lieut.-Col. Haggerty being second in command, Capt. Thomas Francis Meager acting as major, and Capt. John Nugent as adjutant. The regiment numbered one thousand muskets, and was attended by one ambulance only, the other having broken down. The sixty-ninth had good reason to complain that whilst regiments of other divisions were permitted to have baggage and provision wagons, immediately in the rear, the regiment I have to honor to command was peremptorily denied any facilities of the sort. The consequence was that the Sixty-ninth arrived in the field of action greatly fatigued and harassed, and but their high sense of duty and military spirit would not have been adequate to the terrible duties of the day….

Kelly went on to describe the situation as the battle progressed:

…After sustaining and repelling a continuous fire of musketry and artillery, directed on us from the masked positions of the enemy, our regiment formed into line directly in front of the enemy’s battery, charged upon it twice, were finally driven off, owing principally to the panic of the regiment which we had advanced on the battery, and then endeavored to reform. The panic was too general, and the Sixty-ninth had to retreat with the great mass of the Federals.

In this action I have to record, with deep regret, the loss of Col. Corcoran (supposed to be wounded and a prisoner), Acting Lieut.-Col. Haggerty, and others, of whom a corrected list will be speedily forwarded.

Montgomery re-enlisted at New York City as a private on September 3, 1862, mustered into the 170th New York on October 7, and was promoted to first sergeant at some point. As per his muster roll, he was a carpenter (listed at “carpenter 4th”) who was 5′ 11″ tall with hazel eyes, dark hair and a florid complexion. On February 1, 1863, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant and was subsequently promoted to first lieutenant on March 15, 1864. After he was severely wounded in the left elbow at Reams Station, Virginia, on August 25, 1864, he was discharged from military service on October 18, 1864, as a result of his injury. His discharge papers, as per Special Order #327, dated October 1, 1864, noted that he would not receive any pay until “he satisfied the Pay Department that he is not indebted to the Government.” On November 3, 1864, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 38,374. His last residence was on Jefferson Street in Manhattan. His death was caused by cellulitis, a skin infection. In 1905, Margaret Montgomery applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 604,848. Section 126, lot 2458, grave 831.

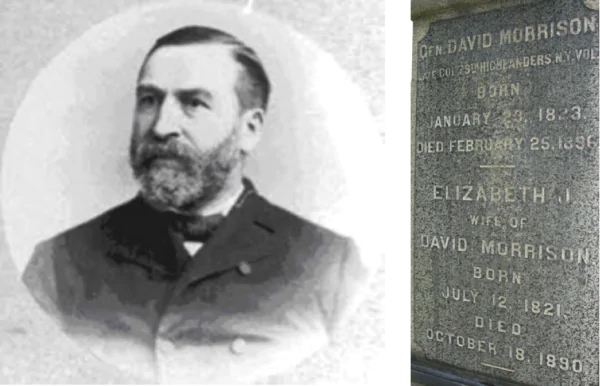

MONTGOMERY, WILLIAM S. (1830-1872). Captain, 79th New York Infantry, Companies F and D. Born in Scotland, Montgomery enlisted as a sergeant at New York City on May 27, 1861, and mustered immediately into Company F of the 79th New York, known familiarly as the Highlanders and composed mainly of men of Scottish heritage. He was promoted to first lieutenant on March 1, 1862, effective upon his transfer to Company D that day. He returned to Company F when he was promoted to captain on October 16, 1862, and served in that rank until he mustered out at New York City on May 31, 1864. Active in organizations that promoted Scottish culture and heritage, Montgomery was an active member of the Scotia Lodge of the Freemasons. His obituary in the New York Herald reported that veterans of the 79th were requested to meet at the Caledonian Club in civilian dress to attend his funeral. He last resided at 31 Sixth Avenue in Manhattan. His death was attributed to sun stroke; the World included his name as among those who succumbed to the heat on that day. The Commercial Adviser reported on August 16, 1872, that Montgomery took sick on Pier No. 20, where he worked on the Anchor line of steamers which traveled to Scotland; he succumbed in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. At the time of his death, he was a widower whose only son was in Scotland.

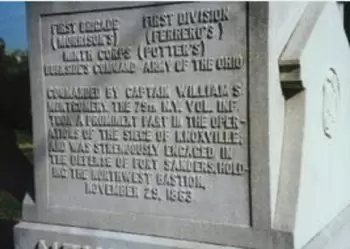

In September 1918, a monument was erected in Knoxville, Tennessee, commemorating the services of the 79th New York Highlanders and the prominent part that the regiment played in the defense of Fort Sanders there. The New York State Legislature, in its 1919 records, indicates that the legislature appropriated $5,000 in 1917 for the monument pursuant to a bill introduced by Alfred J. Gilchrist, a state senator whose father was in the 79th Regiment. The monument, pictured below, is made from Knoxville pink marble and contains many symbols of Scotland such as St. Andrew’s cross and the Scottish emblem of thistles and shields; the coat of arms of the State of New York is also on the monument, and, as a symbol of unity, the figures of a Confederate and Federal soldier clasp hands under an American flag are inscribed. Montgomery’s name is prominent on the plaque (below) which reads:

79TH NEW YORK INFANTRY

(HIGHLANDERS)

1ST BRIGADE 1ST DIVISION

(MORRISON’S) (FERRERO’S)

BURNSIDE’S COMMAND ARMY OF THE OHIO

COMMANDED BY CAPTAIN WILLIAM S. MONTGOMERY, THE 79TH NEW YORK VOLUNTEER INFANTRY TOOK A PROMINENT PART IN THE OPERATIONS OF THE SIEGE OF KNOXVILLE; AND WAS STRENUOUSLY ENGAGED IN THE DEFENSE OF FORT SANDERS, HOLDING THE NORTHWEST BASTION, NOVEMBER 29, 1863.

Section 189, lot 18701.

MOOD, JAMES B. OAKLEY (1842-1864). Sergeant, 13th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company D. Mood was born in New York. In 1855, he was a student at the New-York Conference Seminary in Charlottesville, Schoharie County, New York; that same year, his family was living in New York City. Mood’s father, Peter, who is buried in the same family lot, was a renowned silversmith who learned his craft from his father in Charleston, South Carolina, and subsequently had a partnership with his brother John Mood in Charleston, then, starting in 1841, worked as a silversmith in New York City; Peter Mood was listed as a dealer of fancy goods in the 1857 New York City Directory.

At the start of the Civil War, James Mood resided on Morton Street in Manhattan. After enlisting as a sergeant to serve for three months on May 28, 1862, and mustering into Company D of the 13th Regiment (an Artillery Regiment) on that date, he mustered out on September 12 with his company at Brooklyn. He returned to service as a private when the 13th was reactivated for 30 days in 1863 and died of typhoid in Baltimore, Maryland, on November 17, 1864. As per his obituary in The New York Times, his funeral was held at his parents’ home at 81 Morton Street in Baltimore. Section 12, lot 7656.

MOODY, MATTHEW HENRY (1845-1911). Captain, 23rd Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company C. Moody was born in New York and educated in Brooklyn. As per his obituary in the New York Tribune, Moody was a captain of Company C in the 23rd Regiment during the Civil War. No further details of his service are known. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) records for 1866 report that he had earned $600 that year; the 1867 Brooklyn Directory indicates that he was working as a clerk. As per the 1870 census, Moody lived in Brooklyn with his mother, siblings, and others; he was single, and worked as a leather dealer. The 1880 census indicates that he was married with one child, lived in Brooklyn, and was in the leather manufacturing business. The 1906 New York City Directory reports that he lived at 91 Gold Street. He died in a runaway accident in Parkdale, Oregon, on June 19, 1911. His obituary notes that before relocating to Oregon, Moody had been a longtime Brooklyn resident. Section 70, lot 363.

MOORE, ALFRED (1837-1910). Private, 84th New York (14th Brooklyn) Infantry, Company H. Born in London, England, he immigrated to the United States in 1858. The 1860 census reports that he lived with the family of William Payne; Moore was not a relative of Payne’s but was his apprentice upholsterer. During the Civil War, he enlisted at Brooklyn on April 18, 1861, and mustered into the 14th Brooklyn on May 23. Moore’s muster roll indicates that he was an upholsterer. During his service, he was captured in action and taken as a prisoner of war on August 28, 1862, at Groveton, Virginia, and exchanged on October 15, 1862. One biography indicates that he appeared before a court-martial on February 1, 1864, for being absent (AWOL) for six weeks but he received no punishment. He mustered out on June 6, 1864, at New York City. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which confirms his Civil War service, Moore re-enlisted in the 14th Regiment, New York State National Guard, and served until 1888.

The censuses of 1870 and 1880 list Moore’s occupation as upholsterer; he had an upholstery business in a two-story building in Brooklyn that employed seven people. After leaving the National Guard in 1888, he became a member of the War Veterans Association of the Fourteenth Regiment. An article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on January 19, 1896, about the funeral of Brigadier General Edward Brush Fowler (see), reports that Moore was part of the honor guard when Fowler lay in state at Brooklyn’s City Hall. The census of 1900 notes that Moore was a naturalized citizen. In 1908, his application for an invalid pension was granted, certificate 1,150,862. His last residence was at 211 Schenectady Avenue in Brooklyn. His death was caused by gastroenteritis. He bequeathed $4,000 to one of his daughters; the rest of his estate, consisting of real and personal property, was left to his two sons and two other daughters. Section 4, lot 32956, grave 2.

MOORE, AUGUSTUS G. (1843-1865). Private, 145th New York Infantry, Company D. Born in New York, Moore enlisted at New York City as a private on August 19, 1862, and mustered immediately into the 145th. Other details of his service are not known. His last residence was on 62nd Street and Second Avenue in Manhattan where he died from chronic diarrhea. Section 80, lot 10822.

MOORE, CHARLES A. (1828-1918). Captain, 47th New York Infantry, Company G. Born in New York City, Moore was working as a clerk at the time of the 1850 census. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a captain on August 15, 1861, at East New York, and mustered into the 47th New York. The Veterans Census of 1890 indicates that he was wounded at James Island, South Carolina, in October 1861. He was discharged on September 10, 1864. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which confirms his Civil War service, notes that he was acting colonel of the 47th for four months, commanding the regiment before the Battle of Petersburg, Virginia. The obituary also notes that he earned numerous Congressional medals for distinguished service in many battles and that he always wore them.

The 1870 and 1880 censuses report that Moore was a clerk in a bonded warehouse. Moore was also active in the Volunteer Fire Department for fourteen years. His last residence was 95 Ross Street in Brooklyn. His obituary reports that he died shortly before his 60th wedding anniversary. In 1918, Josephine Moore, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 870,514.Section 199, lot 36015, grave 1560.

MOORE, EDWIN M. (1839-1926). Private, 71st Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company G. A New Yorker by birth, Moore enlisted there as a private on May 28, 1862, mustered into the 71st that day, and mustered out after three months on September 2 at New York City. The census of 1900 reports that he was a bookkeeper for a physician; the census of 1910 reports that he was a bill collector. He was not working at the time of the 1920 census. Moore’s obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle notes that he last lived at 45 Hopkinson Avenue in Brooklyn; as per census records, he had lived there for thirty years. He died from pneumonia. Section 201, lot 24916, grave 3.

MOORE, JOHN P. (1799-1881). Gun supplier to Union Army. Moore, a native of New York City, was educated in the public schools before he dropped out and became an apprentice to Benjamin Cooper, a gun smith. His sporting goods store was one of the first established in New York City in 1822 or 1823 at 206 Broadway; the business later moved next door to 204 Broadway. A balance sheet, published by the New York State Legislature in 1838, notes a purchase of flints for $1.00 from Moore & Baker. Moore was also allied with Samuel Colt, the inventor of pistols which bore his name. In Transactions of the American Institute of the City of New York (1852) it is reported that Moore was a judge in a firearms competition that awarded Colt a gold medal and diploma for “the best revolving pistols of superior workmanship.” In 1855, Colt (who manufactured his revolvers in Hartford, Connecticut) presented Moore with a custom Pocket Percussion Revolver, now part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection, the handle of which was carved from the Charter Oak, an ancient tree revered as a symbol of Connecticut’s struggle for liberty. After his sons, George and Henry T., joined the firm in 1855, the business became known as John P. Moore & Sons. As of January 31, 1860, when he retired, the firm’s name was changed to John P. Moore’s Sons.

During the Civil War, John P. Moore’s Sons, was a major supplier of rifles for the Union Army. As per the IRS Tax Assessments for 1862, the business was valued at $10,859, a substantial sum for that time, and owed taxes of $325.77. In 1863, the business relocated to 208 Broadway. After the Civil War, the store began to offer an extensive line of fishing tackle. The 1878 New York City Directory lists John P. Moore’s Sons as a gun business at 808 Broadway in Manhattan. As per his obituary in The New York Times, he was very active after he retired from his business. For many years, Moore was the president of the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, and took pride in the success of its Apprentices’ Library. He was also Director of the Jefferson Fire Insurance Company, a position he held for 25 years, and a director of the Mechanics’ Bank. That obituary notes that he well-known for his integrity and honesty in business. In 1885, the business was at 302 Broadway and specialized in guns and rifles, pistols, sporting goods, fishing tackle, ammunition and other gunsmen’s supplies. Ads from the business in the 1880s are below. He last lived at 124 Madison Avenue in Manhattan. Section 161, lot 13280.

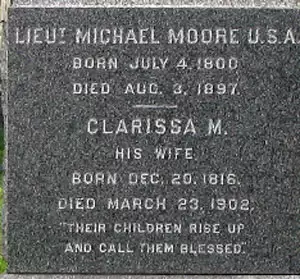

MOORE, MICHAEL (1800-1897). Second lieutenant, United States Army. A native of New York City, Moore grew up in the Canal Street area of Manhattan. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle notes that his father fought in the American Revolution and took part in the surprise attack on the Hessians at Trenton, New Jersey. Michael Moore had a long career of military service dating back to 1812, including an enlistment as a sergeant on May 4, 1841, in the United States Army General Services, and continuing through December 15, 1870. His obituary in The New York Times, August 4, 1897, cited, “Moore’s first appointment was as a drummer boy in the Company of Captain John Sproull. With an older brother he made his way to Albany just at the breaking out of the War of 1812 and enlisted. His regiment participated in the assault and capture of Fort George, Canada, May 27, 1813. He fought the battle of Stony Creek, and later in the campaign at Sackett’s Harbor and on the St. Lawrence River.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reports that he immediately re-enlisted in the Army after the end of the War of 1812 and became a member of the 2nd Regiment of Infantry. In 1821, he was detailed to Sault Ste. Marie and in 1826, was a member of Governor Lewis Cass’s expedition to negotiate a peace treaty with the Indians. (Cass was governor of the Michigan Territory.) Moore served against the Indians in the West and South and fought in the Black Hawk and Seminole Wars. In 1841 he was stationed at the recruiting office at Bedloe’s Island, and remained on active duty there until 1869, when he received his commission as 2nd Lieutenant.”

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reports that although on the retired list as of 1872, he continued his interest in military affairs. He was a charter member of the Military Society of the War of 1812 and an honorary member of the Military Order of Foreign Wars. He had been married for sixty-three years. Moore last resided at 20 Seventh Avenue in Brooklyn. His obituary notes that he died from “extreme old age,” but he had been incapacitated after breaking his hip a few years before his death. As per an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on August 5, 1897, Moore’s funeral, at his late residence, was very simple and limited to family and a few intimate friends. The article reports that in accordance with his widow’s wishes, there were no military displays or tributes at his services. He was laid to rest in a plain black casket; a medal of the Society of the War of 1812 and the button of the Military Order of Foreign Wars were placed on his heart. In 1899, Clarissa C. Moore, applied for a widow’s pension, application 662,622, but there is no certificate number. Section 138, lot 27103, graves 7 and 8.

MOORE, WALLACE L. (1839-1862). Private, 12th New York Infantry, Company E. A New Yorker by birth, the 1860 census reports that he was a clerk. During the Civil War, Moore enlisted as a private at New York City on January 2, 1862, and mustered into the 12th New York on January 16. He died of typhoid fever on April 23 of that year at Chesapeake General Hospital near Fortress Monroe, Virginia, and was interred at Green-Wood four days later. His death was announced in the New York Tribune on April 26 and in The New York Times in its quarterly report of deaths in the Old Point area on July 27, 1862. In 1891, Harriet Moore, his mother, applied for and received a pension, certificate 339,590. Section 16, lot 11096.

MOORE, WALTER (1842-1912). Corporal, 90th New York Infantry, Companies G and D. A native of England, his family immigrated to the United States in 1852. As per his obituary in The New York Times, which confirms his Civil War service, he first served in the 14th Brooklyn Regiment. He enlisted as a private and mustered into Company G of the 90th New York on August 23, 1862, at New York City. Transferred to Company D on November 28, 1864, he was promoted to corporal on March 4, 1865, and mustered out on June 3, 1865, at Washington, D.C.

Moore was a member of the Stephen H. Thatford (see) Post #3 of the G.A.R. The 1870 and 1880 censuses and the 1878 Brooklyn Directory report that was employed as a stair-builder. In 1871, Moore’s application for an invalid pension was granted, certificate 721,843. The Veterans Schedule of 1890 confirms his Civil War service. As per the census of 1900, he was a carpenter; he was not working at the time of the 1910 census. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reports that he belonged to several fraternal organizations and had lived in Brooklyn for more than sixty years. That obituary indicates that Moore died after a protracted illness that was linked to the hardships he had endured during his Civil War service. His last residence was 476 16th Street in Brooklyn. Shortly after his death in 1912, Hannah Moore, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 744,850. Section 132, lot 33587.

MOORE, WILLIAM H. (1826-1883). Private, 87th New York Infantry, Company B; 173rd New York Infantry, Company B. A New Yorker by birth, he enlisted at Brooklyn on August 28, 1862, mustered immediately into the 87th, and was transferred into the 173rd New York on September 11. Further details are unknown. His death was attributed to paralysis. Section H, lot 17648.

MOORE, WILLIAM J. (?-?). Unknown soldier history. A Civil War veteran’s gravestone was ordered for him in 1895 to be placed at Green-Wood. His soldier history and his interment location at Green-Wood are unknown. Section ?, lot ?.

MOORES, JR., FREDERICK WASHINGTON (or FRANCIS, F. W.) (1842-1882). Acting third assistant engineer, United States Navy. Moores, the son of a Navy master, was born in Wethersfield, Connecticut, in 1842, although cemetery records incorrectly list his birth year as 1852 and his given name as Francis, similar to his mother’s name (Frances Stillman Moores). He was educated in Boston, Massachusetts, and attended Norwich University from 1861 through 1863, where he was a member of the Pi Kappa Alpha Freshman Fraternity.