KIMMEL, ALEXANDER F. (1823-1868). First sergeant, 5th New York Infantry, Company D. A native New Yorker, Kimmel enlisted at New York City as a first sergeant on April 25, 1861, and mustered into the 5th New York a month later on May 9. A clerk by trade, he was 5′ 10½” with blue eyes and black hair.

Civil War Bio Search

During his military service, he was reduced to sergeant at his own request on November 13, 1861, and asked to be reduced to private on December 13 of that year. The reductions in rank came about after he was arrested for failure to quiet his men who were talking after taps were played. After bouts of sickness at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, in August 1862, and a stay at Craney Island Hospital in Virginia, he was discharged for disability due to chronic hepatitis at Fort Monroe, Virginia, on March 8, 1863. Kimmel last resided at 28 East 128th Street in Manhattan. His death was caused by heart disease. Section 42, lot 2675.

KIMMENS (or KIMMONS), JOHN (1827-1902). Private, 7th Connecticut Infantry, Company B. Kimmens, a native of New York City, was a private in the 7th Connecticut. The details of his service are unknown. He applied for and received an invalid pension in 1891, certificate 976,836. His last residence was 593 6th Street, Brooklyn. Heart disease was the cause of his death. His widow applied for and received a pension, certificate 504,909. Section 206, lot 31139.

KING, EDWARD (1847-1891). First class fireman, United States Navy. Originally from Ireland, King enlisted as a fireman in the United States Navy at Brooklyn in August 1862. He served on the USS Wabash, Magnolia, and Metacomet. He re-enlisted as a second class fireman on September 22, 1863, and served on the USS North Carolina (until November 25), Camelia (until July 15, 1864), Wabash (until August 31) and was discharged from the Princeton on October 30, 1864. Subsequently, he enlisted as a seaman on November 23, 1864, and served on the USS North Carolina (until December 10), Potomac (until December 31), and was discharged from the Metacomet as a first class fireman on August 15, 1865. (His widow’s pension application states that he suffered from fevers and might have been discharged for disability but that is not noted on his pension records.) King received a pension from the Navy, certificate 9,463.

According to his death certificate, he worked as a sailor. He last lived at 340 17th Street in Brooklyn and was originally interred at Cypress Hills Cemetery in Queens, New York, but was removed to Green-Wood in 1916. Sarah King, his widow, applied for a pension in 1893 that was granted under certificate 9,493. Clarinda King, their daughter, appealed to the pension board to continue giving the widow’s pension to her in 1945, attesting to her single status and the fact that she cared for her mother, an invalid for much of her life who died in 1916, and was no longer able to support herself at age 68. Section 202, lot 28285, grave 1.

KING, FRANK (1842-1885). Fire department foreman; Civil War veteran. Born in New York City, King joined Engine 16 of the Volunteer Fire Department at an early age, but enlisted in a New York State regiment at the outbreak of the Civil War, where he served “with credit.” After a time, he joined the Navy and remained in the flagship corps until the war ended.

King rejoined the fire department upon his return, receiving an appointment as a fireman in 1868 and achieving the rank of foreman of Engine 13 by the middle of 1873. King had a slight physique but was renowned for his ability to “withstand more heat and smoke than men more robust in appearance.” Contemporaries also noted King’s attention to the less fortunate, as he frequently cared for the sick and needy despite his own “meager means.”

He died of a kidney ailment, Bright’s disease (known today as acute nephritis); colleagues blamed the malady on “exposure” King suffered during a serious fire on College Place two months before, although this is medically unlikely. King’s fire department comrades attended his funeral procession from his home on MacDougal Street across the Brooklyn Bridge to Green-Wood, where he was interred with Masonic ceremonies. Section 206, lot 21704.

KING, GILBERT SNOWDEN (1839-1908). Private, 83rd New York Infantry, Company C. Born in New York, King enlisted at New York City on May 27, 1861, and mustered into the 83rd New York that day. After being wounded at Antietam, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, he was discharged for disability two months later on November 11 at Frederick, Maryland. His application for an invalid pension was granted, certificate 17,086. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was a member of the Erastus T. Tefft Post #335 of the G.A.R.; members of the organization were invited to attend his funeral. King last lived in Brooklyn but died from Bright’s disease in Los Angeles. His widow, Eunice King, applied for a pension in 1909, application 911,990, but there is no certification number. Section 198, lot 29486, grave 7.

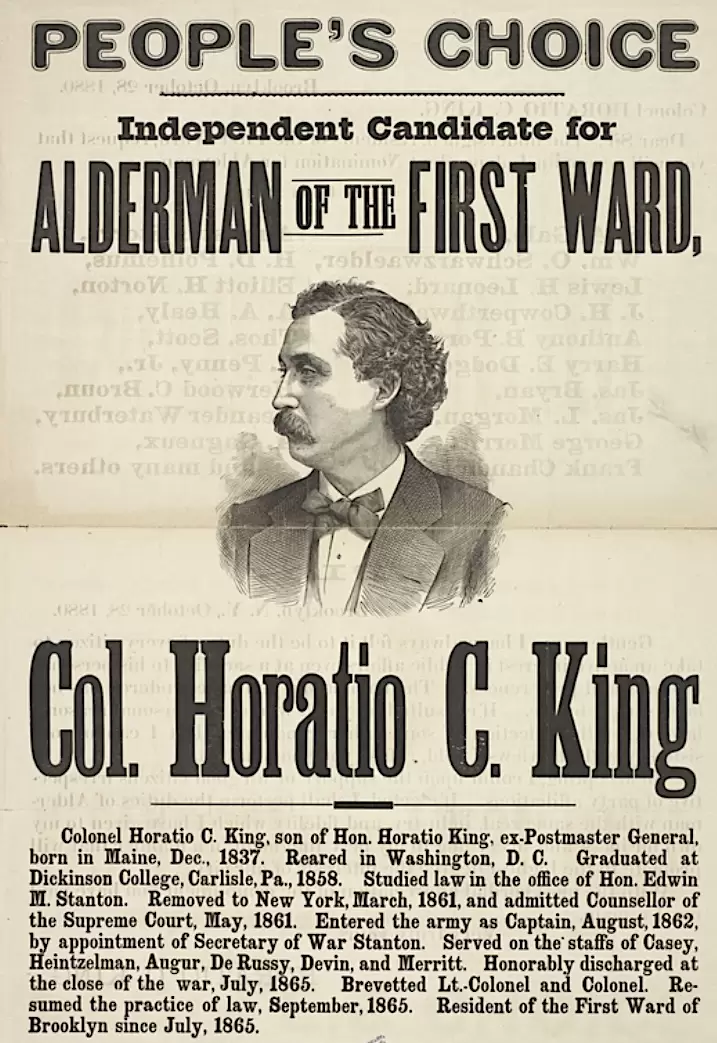

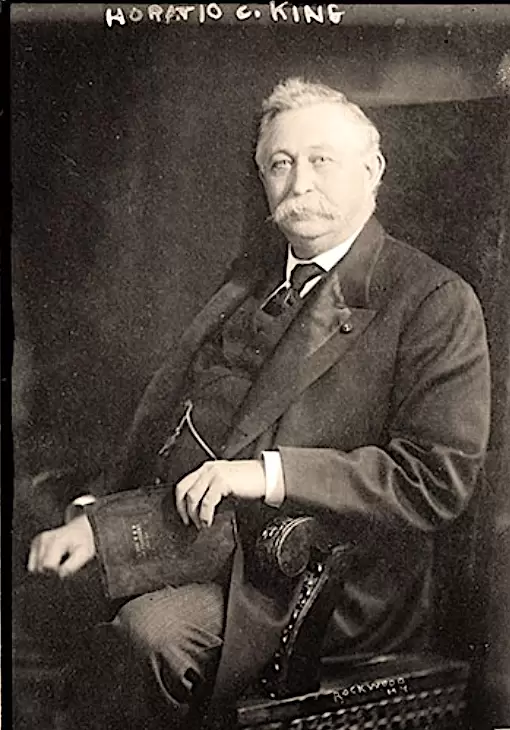

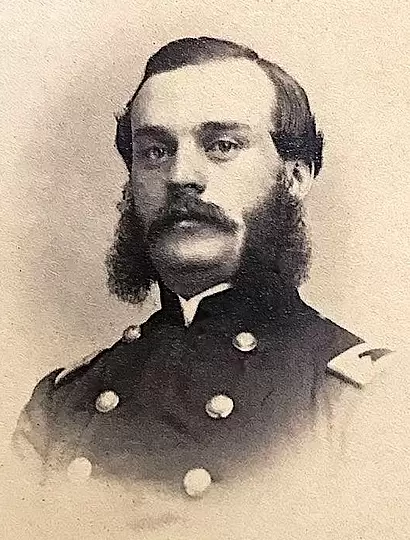

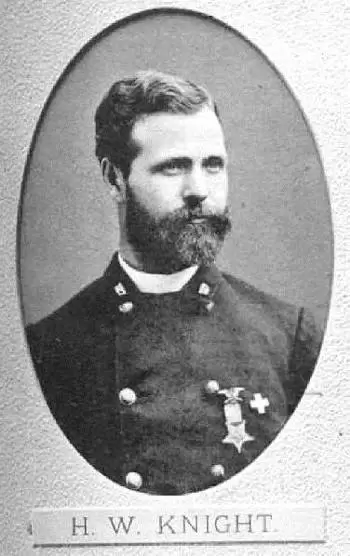

KING, HORATIO COLLINS (1837-1918). Medal of Honor recipient; colonel, lieutenant colonel and major by brevet; major and quartermaster, United States Volunteers. Born in Portland, Maine, King’s father was the Postmaster General of the United States under President Buchanan. He grew up in Washington, D.C., and was an 1858 graduate of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where his uncle Charles Collins was its president. He studied law in the office of Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War in the Lincoln administration), was admitted to the bar in 1861, but shortly thereafter went off to fight in the Civil War, enlisting at Brooklyn as a captain on August 19, 1862, and being commissioned into the United States Army’s Quartermaster’s Department that day. He served in the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the Shenandoah, headed the commissary department of the Army of the Potomac 1864-65 as major and quartermaster of the United States Volunteers, and was brevetted major, lieutenant colonel and colonel in 1865. His brevet to colonel cited his gallantry at the Battle of Five Forks, Virginia.

King was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1897 for his actions near Dinwiddie Courthouse, Virginia, on March 31, 1865. His citation reads: “While serving as a volunteer aide, carried orders to the reserve brigade and participated with it in the charge which repulsed the enemy.” It was from his supplies that were drawn provisions for the Confederates who had surrendered with Lee at Appomattox. Additional information on his Medal of Honor follows (from W. F. Beyer and O. F. Keydel, Deeds of Valor, How America’s Civil War Heroes Won the Congressional Medal of Honor (originally published in 1905):

On the 31st of March, 1865, Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps developed two divisions of Confederate infantry and one of cavalry near Five Forks, Va., and Major Horatio King, chief quartermaster of the first division, feeling that he could safely leave his train in charge of the senior brigade quartermaster, tendered his services to General Devin as a volunteer aide on his staff and was granted permission to accompany him. Owing to the wooded character of the country the cavalry fought dismounted. The ground was stubbornly contested until about four P.M., when a report was brought from the Seventh Pennsylvania Cavalry that the Federal line was driven back. At this time Major King was the only staff officer remaining with General Devin, commanding the division, and he was requested to hunt up the reserve brigade under General Gibbs and hurry them to the aid of the Second Brigade. The reserve was somewhere on the extreme left of the line, so, following the direction of the firing with all possible speed for about three-quarters of a mile, the major found General Gibbs, delivered his orders, and proceeded with him at once to the critical position where the brigade was deployed. They arrived just in time to repel a charge of the Confederate infantry and save the line from serious disaster, Major King accompanying General Gibbs and participating in the charge.

The fighting continued until dark, when, finding that the troops he had were unequal to the task of dislodging the Confederates from their strong works, General Devin withdrew his forces to the neighborhood of Dinwiddie Court House. On the following day, in consequence of the imminent danger of the train, General Sheridan directed Major King to return and resume charge.

He was also active in fund-raising fairs for the Sanitary Commission, a pre-cursor to the Red Cross and the U.S.O., that treated the sick and wounded, worked to improve sanitary conditions in camps, and offered financial help to soldiers. The Brooklyn Fair, held at the Academy of Music on Montague Street in March 1864, raised $400,000, the greatest amount to that date. After the War, King married his second wife, Esther Augusta Howard, whose father, Captain John T. Howard, served with him.

He returned to the practice of law in New York until 1871, commanded the 11th Brigade, New York National Guard in 1876, and was appointed Judge Advocate General of New York in 1883, with the rank of brigadier general. In the 1870s he was associate editor of the New York Star and publisher of the Christian at Work and the Christian Union. He also contributed his work to magazines, and wrote The Brooklyn Congregational Council (1876), King’s Guide to Regimental Courts-Martial (1882), and edited Proceedings of the Army of the Potomac (1879-1887). King served as secretary of the Society of the Army of the Potomac from 1877-1904, and became president of that organization in 1904.

Active in civic and military organizations, he was a member of the G.A.R., where he served as post commander for two years and department judge advocate general for one year, the Freemasons, the Elks, and a charter member of the New York Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion. In addition, he was a member of the Brooklyn Board of Education for 10 years and a member of the Monuments’ Commission. King was defeated when he ran for Secretary of State of New York in 1895 as a Democrat and then ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1896 for the Sound Money Party. King was also. Devoted to his alma mater, Dickinson College, he was a trustee from 1896-1918, and wrote the school song, Noble Dickinsonia. He was a resident of Brooklyn and served as the secretary of Plymouth Church there. His death was caused by myocarditis. Section 93, lot 33, grave 76.

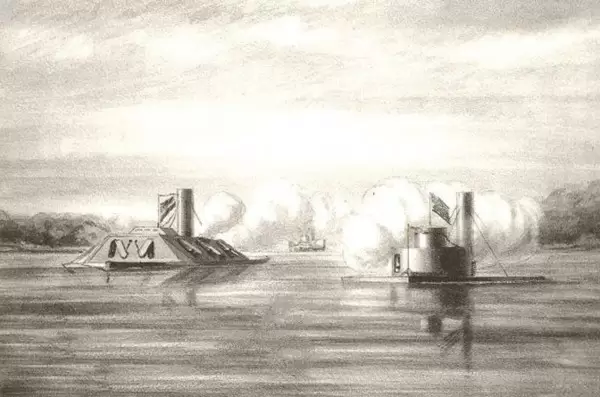

KING, LESLIE G. (or R.) (1841-1919). Second assistant engineer, Confederate States of America Navy; private, 9th Virginia Infantry, Company K, Confederate States of America. Born in Virginia, King resided in Portsmouth, Virginia, and was employed as an engineer’s apprentice at the start of the Civil War. As per military records in the National Archives, he enlisted in the 9th Virginia Infantry on April 20, 1861, at Portsmouth, Virginia, and mustered into service 10 days later. On June 30, 1861, he was mustered into Confederate Navy service. However, his name appeared on the regimental returns of the 9th Virginia Infantry, Company K, for December-February, 1862. On April 26, 1862, by special order of the Confederate Secretary of War, he was transferred to Captain James Mulligan’s signal corps unit.

He first served as a private in the 9th Virginia Infantry, known familiarly as the Old Dominion Guard. Subsequently, he enlisted on April 29, 1862, as a third assistant engineer and was commissioned into the Confederate Navy on that day. From 1862-1863, he served on the CSS Georgia, which was part of the Savannah Squadron, and then was assigned to the CSS Atlanta. The Atlanta had been modified into an armored ship but the modifications made it difficult for her to operate in shallow waters and her armored roof made the interior of the ship turn into a humid oven in hot weather.

Captured while serving aboard the Atlanta by the Union forces on board the USS Weehawken (see image below) on June 17, 1863, King was taken as a prisoner of war, sent to Fort Lafayette, New York Harbor, and then held at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor on July 4, 1863. On June 2, 1864, he was commissioned into the Provisional Confederate Navy as a second assistant engineer. He was paroled on September 28, 1864, at Fort Warren, Massachusetts, and exchanged on October 18 at Cox’s Wharf, Virginia. On April 15, 1865, he was paroled at Richmond, Virginia. King also served on the CSS Tallahassee (1864), and the CSS Columbia (Charleston Station, 1864-1865). After the War, he was employed for twenty-eight years in the Shipbuilding Department of the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a draftsman. He last resided in Slingerlands, New York, where he died of arteriosclerosis. Section 182, lot 11165.

KING, ROBERT (1823-1878). Captain, 133rd New York Infantry, Company D. Of English birth, he enlisted at New York City as a captain on August 29, 1862, mustered into the 133rd the next month on September 24, and was discharged for disability on August 21, 1863, at New Orleans, Louisiana. King last lived at 385 Cumberland Street in Brooklyn. He succumbed to heart disease. Section 143, lot 22361.

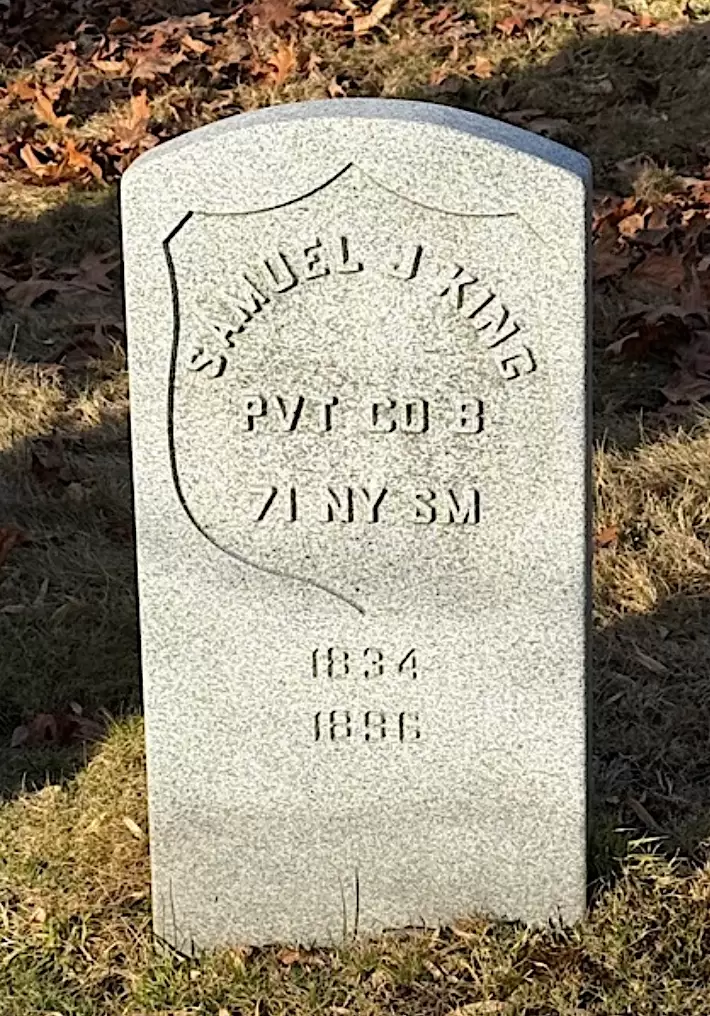

KING, SAMUEL J. (1834-1896). Private, 71st Regiment, New York State Militia, Company B. King enlisted in 1861 as a private for a tour of three months and mustered into Company B of the 71st Regiment. He last lived at 938 Lafayette Avenue in Brooklyn. After his death from pneumonia, Jane G. King, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 448,849. Section 57, lot 28782.

KING, SAMUEL T. (1832-1904). Private, 12th New York Infantry, Companies B and D; 5th New York Veteran Infantry, Company F. He enlisted as a private at New York City on September 4, 1862, mustered immediately into Company B of the 12th New York, was transferred into Company D on June 23, 1863, and was transferred into the 5th New York Veteran Infantry on June 2, 1864. His death was attributed to hemiplegia. Section 114, lot 8999, grave 414.

KING, THEODORE FREDERICK (1843-1917). Captain, 158th New York Infantry, Companies E and C. On August 31, 1862, he enlisted as a first lieutenant at Brooklyn and was commissioned into the 158th on September 3. He was promoted to captain on November 30, 1864, effective upon his transfer to Company C on that day, and was discharged for disability on June 16, 1865. He lived at 14 Central Park West in Manhattan. His death was attributed to apoplexy. Section 35, lot 5120.

KINGHORN, THOMAS (1832-1871). Veterinary surgeon, 6th Ohio Cavalry, Company A. A native of Scotland, Kinghorn enlisted as a farrier on October 18, 1861, and mustered into the 6th Ohio Cavalry on December 6. On December 31 of that month, he was promoted to veterinary surgeon, and was discharged on October 16, 1862. His last residence was 223 9th Avenue in Brooklyn where he died of dropsy. Section A, lot 17244, grave 6.

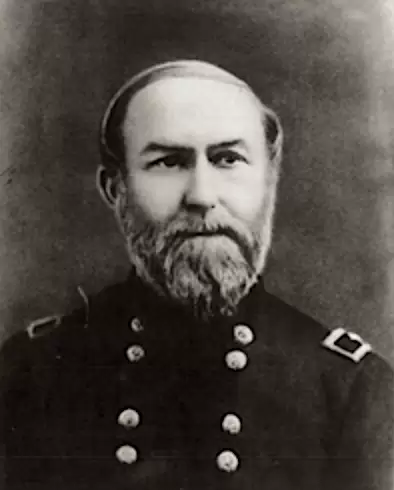

KINGSBURY, CHARLES PEEBLE (1816-1879). Brigadier general, colonel and lieutenant colonel by brevet; major, United States Army Ordnance Department. Born in Clyde, New York, he graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1840 (2nd in a class of 42), and entered the United States Army as a second lieutenant of ordnance. He served in Texas, and fought in the Mexican War as General Wolf’s ordnance officer and on General Taylor’s staff. On February 23, 1847, he was brevetted first lieutenant for “gallant and meritorious conduct in the Battle of Buena Vista, Mexico.” In addition to his military duties, he wrote, Elementary Treatise on Artillery and Infantry (1849), and was a contributor to the American Whig Review, Western Quarterly Review, Putnam’s Monthly, and the Southern Literary Messenger from 1840‑67. After the Mexican War, he served as an inspector of armories and arsenals, was promoted to captain of ordnance on July 1, 1854, in recognition of fourteen years of continuous service, and was principal assistant to the chief of ordnance from March 20, 1861-April 24, 1861.

In April of 1861, Kingsbury was the superintendent of the United States Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, when it was burned to prevent it from falling into Confederate hands. He was chief of ordnance of the Department of the Ohio from June 7, 1861, through August 12, 1861, and the served in that position for the Army of the Potomac from August 12, 1861, through July 15, 1862, during which time he was promoted to colonel and additional aide-de-camp on September 28, 1861.

Kingsbury served in the Peninsula Campaign until he was relieved by reason of sickness at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia. Kingsbury then was on special duty for the War Department aiding Union governors before he became inspector of heavy ordnance at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on November 19, 1862. He was promoted to major on March 3, 1863. He left Pittsburgh on August 1, 1863, for Rock Island, Illinois, where he was in charge of construction of the arsenal there. In 1864-1865, he was engaged in arming and equipping Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota volunteers. He was brevetted lieutenant colonel, colonel and brigadier general on March 13, 1865, commanded the Watertown, Massachusetts, arsenal as of July 19, 1865, and retired from the United States Army with the rank of lieutenant colonel on December 31, 1870. He last resided in Brooklyn. His death was due to heart disease. Section 60, lot 4439.

KINGSLAND, EDWARD W. (1839-1890). Sergeant, 7th Regiment, New York State Militia, Company F. Kingsland enlisted as a sergeant at New York City on April 25, 1861, and mustered into the 7th Regiment. At some point during his service, he was listed as absent on leave. He was a member of the G.A.R. , an organization for Civil War veterans. Kingsland died of phthisis. Section 166, lot 10607.

KINGSLEY, EDWARD (1838-1871). Private, 52nd New York Infantry, Companies H and D. A New Yorker by birth, he enlisted as a private at New York City on September 14, 1863, and mustered immediately into the 52nd New York. After transferring within the regiment to Company D on October 4, 1864, he deserted on October 15. His last residence was 176 Cumberland Street in Brooklyn. His death was caused by consumption. Section 114, lot 17890.

KINGSLEY, HENRY C. (1839-1890). Private, 51st New York Infantry, Company D. A native New Yorker, he enlisted there on October 1, 1861, mustered into the 51st New York that day, and deserted on September 20, 1862, at Antietam, Maryland. He last resided on Smith Street in Brooklyn. Pneumonia was the cause of his death. Section 59, lot 3681.

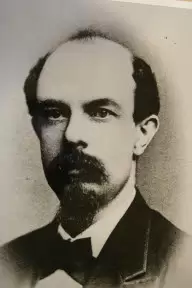

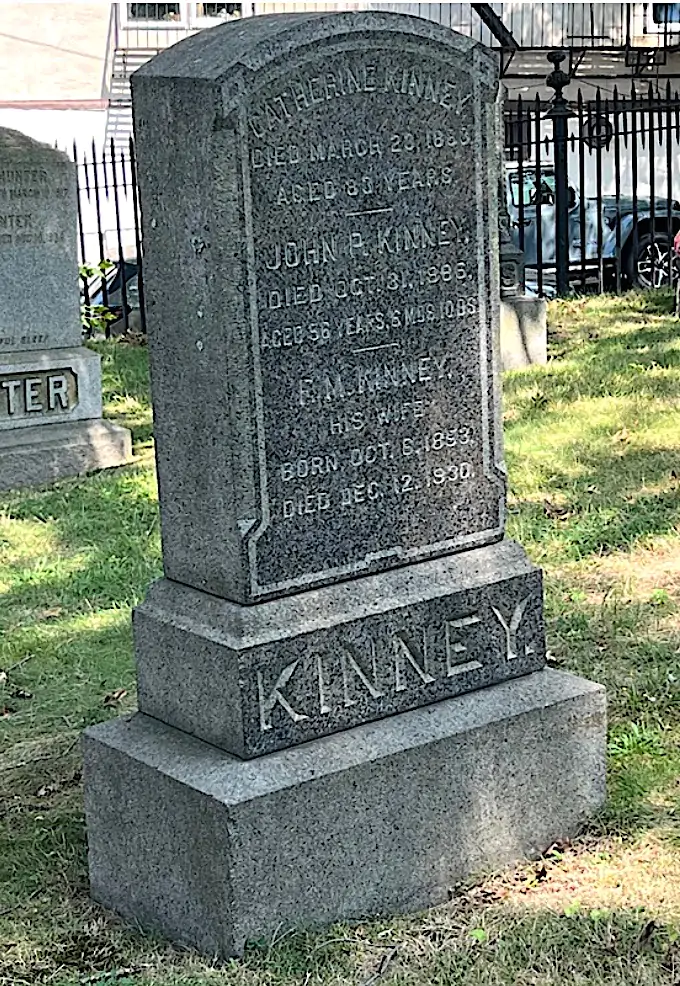

KINNEY, JOHN P. (enlisted as KENNIN, JOHN P.) (1830-1886). Second lieutenant, 145th New York Infantry, Company E. Kinney was born in Ireland. Using the alias John P. Kennin, he enlisted as a first sergeant at New York City on July 21, 1862, and mustered into the 145th New York on September 11. He was promoted to second lieutenant on April 8, 1863, and mustered out on January 6, 1864. In 1886, his application for an invalid pension was granted, certificate 335,791. His last address was 393 State Street in Brooklyn. Shortly after his death from haematemesis, which causes vomiting of blood, Fredericka Kinney, who is interred with him, was granted a widow’s pension, certificate 293,001. Section M, lot 24208.

KINSEY, CHARLES J. (1834-1912). First lieutenant, 15th New York Heavy Artillery, Companies H, B, and E; quartermaster, 2nd Independent Battery, New York Light Artillery. English by birth, Kinsey enlisted at New York City as a private on June 4, 1861, and mustered into the 2nd New York Light Artillery that same day. At some point, he was promoted to quartermaster and then reduced to ranks before his discharge for disability on April 24, 1862. On October 8, 1863, he re-enlisted as a second lieutenant at Washington, D.C, and was commissioned immediately into Company H of the 15th New York Heavy Artillery. On July 20, 1864, he was promoted to first lieutenant and was transferred to Companies B and E before he was discharged on August 22, 1865, at Washington, D.C.

In 1871, Kinsey applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 125,325. According to the census of 1880, he was a carpenter by trade. Kinsey is listed in the 1890 Veterans Schedule for Brooklyn. His obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle confirmed his Civil War service. Kinsey died from nephritis. His last residence was 332 8th Street in Brooklyn. Section 143, lot 27742, grave 2.

KINTZING, MATTHEW RALSTON (1822-1893). Lieutenant colonel, United States Marine Corps. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Kintzing spent 38 years serving his country, 10 years at sea and 28 on shore duty. He was commissioned second lieutenant in the Marine Corps on September 8, 1841, at which time he was assigned to the Vincennes in the Home Squadron through 1845. Kintzing was then at the Marine Barracks at Philadelphia from 1845-46 prior to his return to the Home Squadron. His various engagements included a shipwreck in the Bahamas and being wounded at Tabasco in the Mexican Gulf in 1847, the year of his promotion to first lieutenant on July 16. After shore duty in Massachusetts, he subsequently spent two years fighting pirates in Africa near Benin and along the Congo coast on the sloop Cumberland, and was promoted to captain on August 1, 1860.

When the Civil War broke out, Kintzing was present at the destruction of the Naval Yard in Norfolk, Virginia, served on board the steamship Roanoke in the Atlantic Blockading Squadron in 1861, and participated in engagements with the Merrimac and at the Sewall’s Point Batteries, Virginia. In 1862, he went to Philadelphia for recruiting service. During his assignment to establish marine barracks at Cairo, Illinois, from 1863-64, he was commissioned lieutenant colonel on June 10, 1864. Kintzing was then assigned to the barracks in Philadelphia and the Mare Island Navy Yard in San Francisco. He was commissioned colonel on December 7, 1867, when he served in Philadelphia, a term lasting until 1877. Subsequent service was at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and a short stint at Norfolk prior to retirement. He last lived at 215 Park Place in Brooklyn, his wife being from a family with longtime roots there. Cirrhosis of the liver caused his death. Section 173, lot 21516, grave 1.

KINZY, FREDERICK (1838-1914). Private, 7th West Virginia Infantry, Companies G and D. Of German origin, Kinzy enlisted as a private and mustered into Company G of the West Virginia Infantry. At some point, he was transferred intra-regimentally to Company D. Further details of his service are unknown. His last residence was 289 6th Street in Brooklyn. Kinzy died from cancer. Section 2, lot 5499, grave 1818.

KIP, HENRY (1839-1897). Private, 22nd Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company D. A native of Chicago, Illinois, Kip enlisted at New York City as a private on May 28, 1862, mustered into the 22nd Regiment the same day, and served until he mustered out after three months on September 5 at New York City. He resided in Chicago at the time of his death from dysentery. Section 34, lot 20710.

KIP (or KIPP), LAWRENCE (1836-1899). Lieutenant colonel, major, and captain by brevet; major and aide-de-camp, United States Volunteers; adjutant, 3rd Light Artillery, United States Army. Kip, who was born in New York, attended the United States Military Academy from July 1, 1853-May 31, 1854. Prior to the Civil War, he enlisted and was commissioned as a second lieutenant on June 30, 1857, and served in the 4th Light Artillery of the United States Army until he transferred into the 3rd Light Artillery on August 27 of that year.

At the start of the Civil War, Kip rose to first lieutenant on May 14, 1861, and to adjutant on September 27. On August 20, 1862, he was promoted to major and aide-de-camp and commissioned that day into the United States Volunteers Aide-de-Camp. On October 1, 1862, Major General Edwin V. Sumner, United States Army, wrote in his field report from Harpers Ferry, Virginia, about the Battle of Antietam, Maryland (September 17), praising Kip, his aide, for his “zeal and devotion.” Sumner noted, “These young men behaved in the most gallant manner, and did all that men could do to aid me throughout this trying battle.” Kip served with United States Volunteers until his resignation on August 15, 1863. On June 11, 1864, he was promoted to captain by brevet for his service at Trevillian Station, Virginia. After re-enlisting as lieutenant colonel on July 13, 1864, he was commissioned into the Field and Staff of the 8th New York Heavy Artillery but declined that commission. He was brevetted to major on March 31, 1865, for actions at Dinwiddie Court House, Virginia, and brevetted to lieutenant colonel on April 1, 1865, for service at Five Forks, Virginia. Kip was promoted to captain on August 13, 1866. Kip last lived in New York City. His death was caused by cancer. Section 19, lot 9005, grave 27.

KIP, THOMAS C. (1840-1890). Musician, 61st New York Infantry. A native New Yorker, he enlisted at New York City on August 26, 1861, and mustered into the 61st as a musician the next month on September 5, but was not assigned. His last address was in Jersey City, New Jersey, where he died of cancer. Section 78, lot 2063.

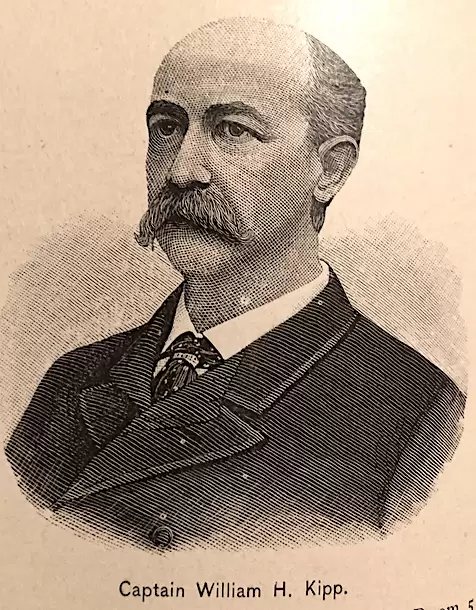

KIPP, WILLIAM HALSTEAD (1839-1918). First lieutenant, 7th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company D. Born in New York City, Kipp enlisted there as a private on April 17, 1861, mustered into the 7th Regiment’s State Militia on April 26, and mustered out with his company on June 3 of that year at New York City. When the 7th Regiment was re-activated on May 25, 1862, and part of the New York State National Guard, he returned to his company as a corporal and mustered out of service after three months on September 5, 1862, at New York City. In 1863, he was commissioned into the 7th Regiment as a first lieutenant and served for 30 days.

After the war, he was a colonel in the 7th Regiment’s Field and Staff where he was brevetted to brigadier general on January 20, 1908, by Governor Hughes in recognition of 50 years of service with the regiment. On November 24, 1884, he was appointed chief clerk of the New York City Police Department and remained on duty until his death from apoplexy in 1918. He was the brother-in-law of Stephen Burdett Hyatt (see). His last residence was 20 West 121st Street in Manhattan. Section 182, lot 9458.

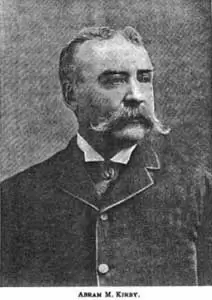

KIRBY, ABRAHAM (or ABRAM) M. (1839-1901). Artificer, 13th Regiment, New York State Militia, Sappers and Miners. Kirby was an artificer with the 13th Regiment for three months in 1861. He last lived at 426 Clinton Street in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to uraemia, a kidney-related disease. Section 205, lot 30155, grave 3.

KIRBY, EDGAR (1836-1912). Second lieutenant, 5th New York Heavy Artillery, Companies H, D, and G. Kirby, a native of New York State, enlisted as a private at New Castle, New York, on September 9, 1862, the same date that he mustered into Company H of the 5th New York Heavy Artillery. He rose to corporal on January 24, 1863, and was commissioned as second lieutenant on June 22, 1863, effective upon his intra-regimental transfer to Company D that day. At some point, he was transferred to Company G. Kirby was dishonorably discharged on or about November 15, 1863. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, he was a Freemason and member of the William McKinley Post #203 of the G.A.R.; members of both organizations were invited to attend his funeral. His last residence was 239 East 238th Street in the Bronx. He succumbed to pneumonia. Section 70, lot 2097.

KIRCHNER, FREDERICK (1827-?). Private, 29th New York Infantry, Company H. He may have been the Frederick Kirchner who, at the age of 34, enlisted at New York City on April 17, 1861, mustered into the 29th New York on June 4, and mustered out at New York City on June 20, 1863. His death was caused by marasmus, a form of severe malnutrition. Section ?, lot ?.

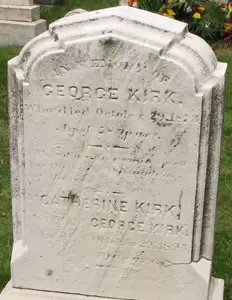

KIRK, GEORGE (1815-1873). Private, 158th New York Infantry, Company B. Of English birth, Kirk enlisted at New York City and served with the 158th New York. Other details are unknown. His last residence was 198 Johnson Street in Brooklyn. The cause of his death was gangrene of the lungs. In 1879, Catherine Kirk, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 307,210. Section 59, lot 1459, grave 26.

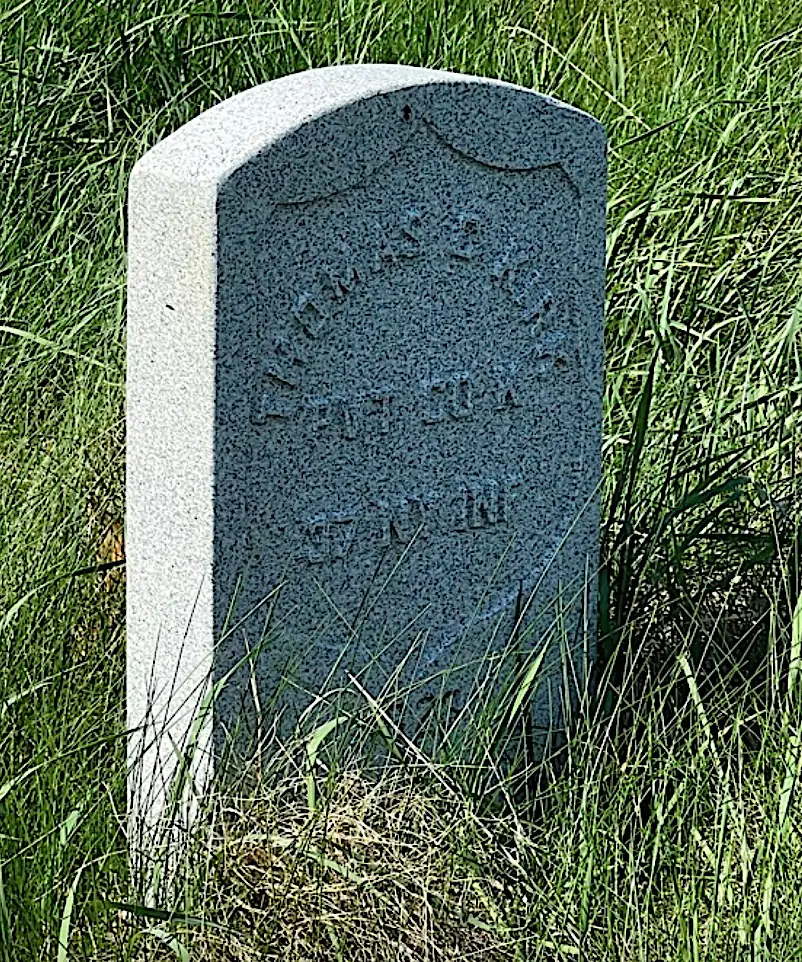

KIRK, THOMAS C. (1823-1868). Private, 37th New York Infantry, Company K. Born in England, he enlisted at New York City as a private on May 25, 1861, and on June 7, 1861, mustered into the 37th New York. He mustered out on June 22, 1863, at New York City. His last residence was 148 Tillary Street in Brooklyn. Section A, lot 8100, grave 963.

KIRKHAM, EDWARD (1834-1904). Corporal, 53rd Pennsylvania Infantry, Company F. Of English birth, he enlisted as a corporal on October 12, 1861, was immediately mustered into the 53rd Pennsylvania Infantry, and was discharged on an unspecified date. In 1864, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 31,894. After the War, he was a chaplain of the G.A.R.’s McPherson-Doane Post #499 and Moses F. O’Dell Post #443 in Brooklyn. Kirkham is listed in the 1890 Brooklyn Veterans Census, a confirmation of his Civil War service. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, members of the Moses F. Odell Post of the G.A.R. were invited to attend his funeral. His last residence was 303 Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn. He died of heart disease. Jane Kirkham applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1905, certificate 603,834. Section 158, lot 17261.

KIRKHAM (or KIRKMAN), THADDEUS (1836-1868). Private, 7th New York Heavy Artillery, Company B. After enlisting as a private at Albany, New York, on August 5, 1862, he mustered into the 7th Heavy Artillery on August 18, and deserted on May 18, 1863, at Fort De Russy in Washington, D.C. He last lived at 11 17th Street in Brooklyn. Section 59, lot 11734, grave 23.

KIRKLAND, CAROLINE MATILDA (1801-1864). Author, organizer of the Brooklyn Sanitary Fair. A native of New York City, Caroline Stansbury Kirkland was a granddaughter of Joseph Stansbury, a Royalist in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during the American Revolution. A student of language and literature, she was educated at her aunt’s girls’ schools in Manhattan and Mamaroneck, New York, and then helped run the school until her marriage in 1828. Her husband, William Kirkland (see), was a professor of classics at Hamilton College in New York. When they moved to Michigan in 1835, the Kirklands were active in the Underground Railroad, shepherding slaves to freedom in Canada. An author, who wrote as Mary Clavers, she specialized in sketches of prairie life. She was the first author to write novels about life on the frontier in A New Home, Who’ll Follow, Or Glimpses of Western Life (1839) based on her experiences. In addition, she wrote Forest Life (1842), and Western Clearings (1845). Kirkland also used the pseudonym Aminadab Peering.

Kirkland’s family returned to New York in 1843 where her husband died accidentally in 1846. After William’s death, she took over his job as editor of the Christian Inquirer and continued to run a girls’ school in her home. Active in literary circles, Edgar Allen Poe wrote a description of her in Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1846, “She is rather above the medium height; eyes and hair dark; features somewhat small, with no marked characteristics but the whole countenance beams with benevolence and intellect.” Her home became a salon for writers including Poe, William Cullen Bryant, Elizabeth Drew Stoddard and others. She traveled to Europe in 1848 and 1850, while working as a writer for Union Magazine, and met Charles Dickens, Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Always interested in the down-trodden, she was on the executive committee of the Home for Discharged Female Convicts. In 1853, she wrote a plea asking for help for these women.

During the Civil War, Kirkland spoke out about the lack of sanitation and supplies for soldiers in the May 1863 issue of the Continental Weekly. She was also an active organizer of the Brooklyn (Long Island) Sanitary Fair and member of its Committee on Arms and Trophies. She spent three months devoting her time to preparation for the event. After her sudden death in April 1864, shortly after the Fair opened, women who worked with her said in tribute, “She was greater than her books, or than any single book.” The Fair raised $1.5 million for the Union. Her son, Joseph Kirkland (see), was a noted writer. Section 163, lot 14793.

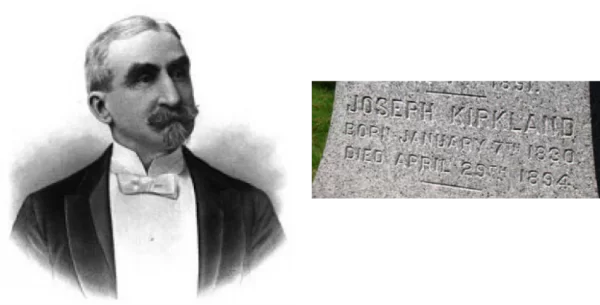

KIRKLAND, JOSEPH (1830-1894). Major by brevet; captain and aide-de-Camp, United States Volunteers; second lieutenant, 12th Illinois Infantry, Company C. Kirkland is not buried at Green-Wood; the cenotaph on his family’s lot honors his memory. Kirkland was born in Geneva, New York. As per his obituary in The New York Times, his father, William Kirkland (see), was a professor of classics at Hamilton College in New York and his mother, Caroline Stansbury Kirkland (see), was a granddaughter of Joseph Stansbury, a Royalist in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during the American Revolution. His grandfather, Joseph Kirkland, was the first mayor of Utica, New York. In 1835, his family moved to Detroit, Michigan, in 1835, where his father directed the Detroit Female Seminary and then lived in Pinckney, Michigan, from 1837-1843, where his mother, who also used the name Mary Clavers, wrote sketches of prairie life. While in Michigan, William Kirkland was active in the Underground Railroad, helping slaves escape to Canada and was a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society there. The family returned to New York in 1843; his father, nearsighted and deaf, died three years later when he accidentally walked off a pier and drowned. Joseph Kirkland then turned to the sea and visited his uncle in England a year later. By 1852, he was a clerk and reader in the offices of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, then moved to Illinois in 1855. A businessman and supervisor of the Tilton [Illinois] Coal Company as of 1858, he was a member of the committee that informed Abraham Lincoln of his nomination for the Presidency in 1860. On January 7, 1861, he wrote to President-elect Abraham Lincoln asking to be considered for the job of private secretary. He wrote:

The post of private secretary seems to be one requiring a rather uncommon combination of literary and business talent. If you have not already selected yours I should like to know it and add one to the number among whom you can take your pick. My own acquaintance with you is not such as would probably recall me to your mind, being confined to the evening you spent at my house in company with Col. Foster, the English Lord Grosvenor and others, but I have many friends among the editorial Fraternity in New York and Chicago (Mr. [William Cullen] Bryant, especially) and many business friends whom you know, and from them I would get letters if you encourage me to do so.

At the onset of the Civil War, he enlisted as a second lieutenant on April 25, 1861, was commissioned into the 12th Illinois on May 2, and mustered out on August 1. When the company was ready to assemble at Cairo, Illinois, Kirkland made sure that the soldiers had blankets, camp kettles and other supplies that the citizens of Chicago had donated to the Union cause. He later wrote that he found it hard to adjust to the realities of war and sought to transfer to an aide-de-camp position. On August 25, 1861, he was commissioned as a full captain into the Aide-de-Camp, U.S. Volunteers, was promoted to full captain and assistant aide-de-camp on August 26, and served as aide-de-camp to General George B. McClellan in the West Virginia campaign before he was assigned to the Adjutant General’s Department on November 1. He served on the staffs of Fitz John Porter (see) during the siege of Yorktown, Virginia, and fought at the Sevens Days Battle. Kirkland came down with jaundice at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, and rejoined the forces prior to the Battle of Antietam, Maryland. He was promoted by brevet to full major on August 20, 1862, He also served under General Ambrose Burnside. During the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862, his horse was shot from under him. He resigned on January 7, 1863, after Porter was relieved of his post.

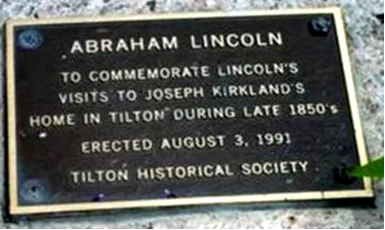

In 1864, Kirkland published the first edition of Prairie Chicken, a Midwestern literary periodical. He went on to study law, scored highest on the exam when he was admitted to the Bar in 1880 and practiced for ten years. Also a novelist and playwright, his works include The Married Flirt (1880); Zury: The Meanest Man in Spring County (1887); The McVeys: An Episode (1888); The Captain of Company K (published serially from 1890-1891 and the winner of a contest sponsored by the Detroit Free Press); The Story of Chicago (1891); and The Chicago Massacre of 1812 (1893). Kirkland became literary editor of the Chicago Tribune in 1889 and co-editor of The History of Chicago in 1893, a work that his daughter took on after his sudden death from a heart attack in 1894. He last lived in Chicago, Illinois. A testimonial by the mayor of Chicago, after Kirkland’s death, said in part, “…Chicago points with pleasure and with pride to the products of his genius in the story of her giant progress, and those other works that have linked his name to hers in a loftier connection. Deservedly classed among her ‘old settlers,’ his whole career has been one of exemplary citizenship.” On August 3, 1991, the Tilton Historical Society dedicated a plaque commemorating Lincoln’s visits to Kirkland’s home in the 1850s. The cenotaph is at section 163, lot 14793; Kirkland is interred at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

KIRKLAND, WILLIAM (1800-1846). Abolitionist. A native of New York, his father, Joseph Kirkland, was the first mayor of Utica, New York. William Kirkland was a professor of classics at Hamilton College in New York and his wife, Caroline Stansbury Kirkland (see), was a granddaughter of Joseph Stansbury, a Royalist in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during the American Revolution. In 1835, the family moved to Detroit, Michigan, where William Kirkland directed the Detroit Female Seminary. He then lived in Pinckney, Michigan, from 1837-1843, where Caroline Kirkland, who wrote under the name Mary Clavers, penned sketches of prairie life. William built a grist mill and tavern in Pinckney and was joined there by two of his brothers. While in Michigan, William Kirkland was active in the Underground Railroad, helping slaves escape to Canada, and was a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society there, serving on the committee to draft the society’s constitution. While rejecting violence, the goal of the Michigan Anti-Slavery Society was “the entire abolition of slavery in the United States of America.” Among its other goals was petitioning Congress to end the slave trade and slavery, extending the right to vote to all men, and helping educate all blacks in Michigan. The family returned to New York City in 1843 and Kirkland was the editor of the New York Evening Mirror and editor and owner of Christian Inquirer. In 1846, nearsighted and deaf, he accidentally walked off a pier and drowned. His wife, who is interred with him, took his place as editor and his son, Joseph Kirkland (see), followed in his footsteps as an author and anti-slavery advocate. He last lived at 143 Green Street in Manhattan. Section 163, lot 14793.

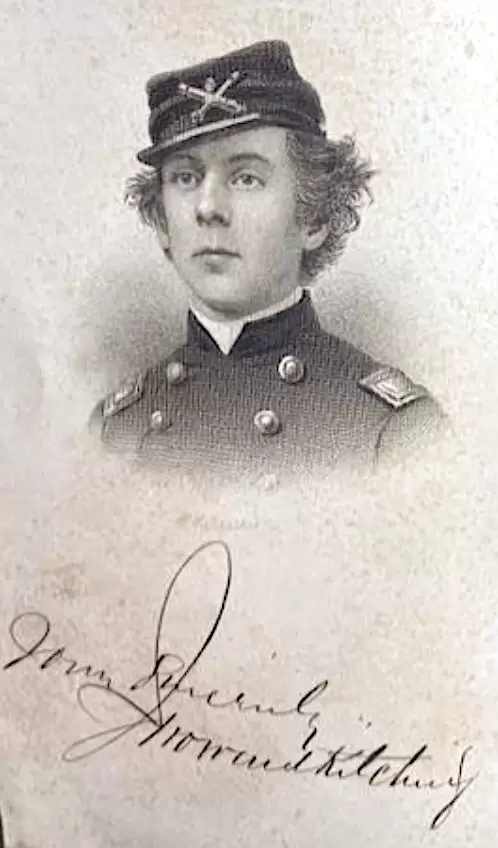

KITCHING, JOHN (or J.) HOWARD (1838-1865). Brigadier general by brevet; colonel, 6th New York Heavy Artillery; captain, 2nd New York Heavy Artillery, Company B. New York City-born, he was, according to the 1850 census, a twelve-year-old living with his teacher and other students in Norwich, Connecticut. He applied for a passport in 1855, at the age of 17, and described himself as 5′ 4″ tall, with gray eyes, a large regular nose, medium mouth, round chin, fair complexion, oval face, and light brown hair. As per the 1860 census, he was living with his parents, John B. and Mary Kitching, in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and was working as a carman.

Howard (as he was called by friends and family and as he signed his many wartime letters home) married Harriette Brittan Ripley in 1860 in an Episcopal Church ceremony at Christ Church in Brooklyn; he had attended Sunday school there. Their son, John Howard Kitching Jr., was born in 1861; their daughter, Edith, was born in 1864.

At the age of 22, and a resident of Dobbs Ferry, New York, where he worked as a merchant and was active in his local church, Kitching enlisted as a captain at New York City on August 19, 1861, and was commissioned into the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery on September 18. However, according to a posthumous tribute to him in the Brooklyn Independent of February 2, 1865, when he arrived with the 2nd in Washington, D.C., and found out it have been assigned to garrison duty, he transferred to the 2nd United States Artillery, Battery D, was given command of a section, and served at the front during the entire Peninsula Campaign. As per that report, “He was with the regulars who covered the retreat of the army from the Chickahominy to Harrison’s Landing. During that terrible conflict of seven days, he scarcely slept or ate.” As per the account of then-Colonel (and later Major General) Emory Upton, as printed in “More than Conqueror,” or Memorials of Col. J. Howard Kitching (published in 1873), at Gaines Mills Kitching’s battery

. . . was exposed to the full view of the enemy, and received much more than its proportion of fire. During the entire battle, he served his guns with great coolness, and was a brilliant example to his men. He received in the breast a most painful contusion from a fragment of a shell, but did not quit his post.

Kitching was discharged from service on July 6, 1862, but, a month later, he re-enlisted and was commissioned into the 6th New York Heavy Artillery as its lieutenant colonel; he was promoted to its colonel on April 1, 1863.

Kitching briefly commanded the Army of the Potomac’s ammunition train in late 1863 and early 1864. He was given command of a brigade in the Army of the Potomac, serving under Generals Gouverneur Warren and U.S. Grant. He led his men at the Battles of the Wilderness (where, according to the Independent, “he fought with great gallantry”), Spotsylvania (where, again according to the Independent, “his brigade held an important post for several hours, against the whole of [Confederate General Richard S.] Ewell’s corps,” and was complimented by Major General George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, for “the gallant manner” that his brigade of 3,000 men, fighting as infantry, “met and checked the persistent attacks of a corps of the enemy, led by one of the ablest generals . . . .” Kitching then led his men at Cold Harbor and Petersburg, Virginia (at The Crater, they were poised to support the assault, but were not ordered in). By mid-August, 1864, he and his brigade had been ordered to Washington, D.C. where he was given command of 13 forts and their garrisons, protecting an eight-mile section of the defenses of the nation’s capital. He took part in the Battle of Fort Stevens in support of those defenses.

On October 2, 1864, Kitching wrote to his father, telling him that he had applied for an honorable discharge, based on his three years of service. That application had been granted and he would be heading home the next day. However, two days later, he wrote again to his “Papa,” telling him that the Secretary of War had revoked the discharge order, and that he was to report immediately to the Army of the Shenandoah under General Phil Sheridan. When Kitching arrived in Harpers Ferry, he was given command of all troops who were joining Sheridan’s army. He soon was given command of a division and his men rejoined him; he now commanded 7,000 men.

In the early morning hours of October 19, 1864, Confederate Major General Jubal Early and his men surprised Sheridan’s Union Army at Cedar Creek, Virginia. The Independent describes Kitching at Cedar Creek:

Encamped by Cedar Creek, at early dawn, the light so dim they could scarce distinguish between friend and foe, the rebels startled them from their slumbers, sweeping down upon them, with their fiendish yell, in overwhelming numbers. The surprise was complete. Having only one battalion of his own regiment, Col. K. rallied his men, and held an important road for several hours, until nine of eleven of his officers were either killed or wounded. One color-sergeant after another was shot down, and they were giving way before a wild onslaught, when Major Jones, who was greatly beloved by the regiment, fell, mortally wounded. Col. K. called out, “Stop, men, you will not let Jones be made a prisoner!” They rallied to a man, and stood their ground until their major was safely carried to the rear. We have heard the colonel tell with tears how many brave young fellows lost their lives in the rescue of an officer they loved so well.

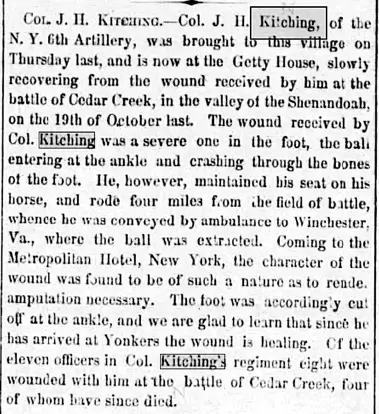

Before the Confederates reached Kitching’s men, who then numbered about 1,000, they too, began to retreat. At that time, Kitching, desperately trying to rally the troops, was severely wounded in the ankle by a Minie ball. He continued to urge his men to stand and fight, though many urged him to leave the field to have his ankle treated. It was only after Major General Sheridan arrived at the battle, and dramatically rallied his army, that Kitching agreed to seek treatment. This report in the Yonkers Statesman, published on December 8, 1864, describes Kitching’s mortal wound:

Kitching, wounded, rode on horseback for four miles before he and a captain accompanying him found an assistant surgeon, who advised Kitching to immediately find an ambulance to transport him for treatment. When a vacant ambulance could not be found, a stretcher made of tent fabric and poles was fashioned and stragglers carried him to the rear. Finally, an ambulance carrying a dead soldier was found, Kitching was placed beside the deceased and was driven to Winchester. Word reached him there of Sheridan’s triumph; Kitching’s response: “If this be true, I should be willing to lose another leg.”

Howard telegraphed home that he had been slightly wounded. He was brought back to New York City by railroad and stayed at the Metropolitan Hotel on Broadway. His daughter was born on November 14, in Yonkers. That same day, his doctors informed him that an amputation of his ankle was necessary. After the amputation, his fever grew worse. On December 1, he was taken to Yonkers. Suffering in pain and fever, and with a racking cough, he rallied for a while, but died on January 10, 1865.

Kitching returned home to Dobbs Ferry, in the hopes of recovery. He received many messages of encouragement from those who had served under him, and just a week before his death, he wrote to his regiment that “as soon as he could mount his horse he would be with them, to lead them in the anticipated assault” to end the war. But that was not to be; he died from his wounds on January 11, 1865. J. Howard Kitching was just 26 years old. The Independent memorialized him as “frank, generous warm-hearted, with a face beaming with intelligence.” Posthumously, he was brevetted to brigadier general dating from August 1, 1864, for “meritorious and distinguished service during the campaign of 1864 before Richmond.” Six days after his death, the officers of the Sixth Regiment, New York Heavy Artillery, adopted a resolution that read, in part:

Resolved, That the character of General Kitching as an officer and a gentleman, was such as commanded our highest respect and esteem. His qualities as a soldier and a leader, whether displayed in the quiet of camp or in the storm of battle always secured the earnest confidence of all. We feel that no one can supply his place with us. He died for his country, but his memory will ever live in our hearts as that of a good man, a true soldier, and a gallant officer.

On January 13, 1865, as reported in the Brooklyn Eagle, nearly 300 members of the 23rd Regiment of New York State’s National Guard marched beside Kitching’s remains as they were transported to Green-Wood. Members of Company A fired a rifle salute over his grave. In 1865, Harriette Kitching, received a widow’s pension, application 98,207.

The Brooklyn Independent, on February 2, 1865, eulogized Kitching:

The noble army of martyrs is gathering its recruits, beyond the river, day by day; the brave and the beautiful, those who were the light and the joy of happy households, are giving up their young lives for their country, and should not those who love that country remember and record the memory of the noble dead? These are the things that make the glory of any land.

Among the noblest of those who have died for their country during this wicked rebellion was Col. J. Howard Kitching . . . .

Section 132, lot 362.

KITSON, GEORGE (1841-1865). Private, New York Marine Light Artillery, Company F. Originally from Ireland, Kitson enlisted at New York City as a private on February 9, 1862, the same day that he mustered into the New York Marine Light Artillery. He was discharged at New Berne, North Carolina, on January 17, 1863. His last residence was 2097 Wooster Street in Manhattan. Section 114, lot 16491.

KLEE, HENRY (1842-1914). Private, 1st New York Light Artillery, Battery I. Of German birth, he enlisted as a private at Buffalo, New York, on October 28, 1861, mustered into the 1st New York Light Artillery on January 6, 1862, and mustered out on June 23, 1865, at Buffalo. He last resided at 471 13th Street in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to septicaemia. Section 200, lot 23807, grave 2.

KLEEMANN, ERNST (or ERNEST) (1843-1899). Private, 15th New York Heavy Artillery, Company B. After Kleeman, who was born in Germany, enlisted at New York City as a private on December 31, 1863, he mustered into Company B of the 15th New York Heavy Artillery the same day. He served the remainder of the Civil War, was taken prisoner on an unknown date, and was discharged at Mower Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 26, 1865. He last lived in Patchogue, Long Island. Uraemia was the cause of his death. Section 296, lot 31244, grave 2.

KLEIN, HENRY (1827-1896). Captain, 52nd New York Infantry, Company B. After enlisting as a captain at New York City on August 9, 1861, he was commissioned into the 52nd on November 1, and discharged on October 27, 1862. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, he last lived at 9 St. Luke’s Street and was a Freemason. Klein died of Bright’s disease. Section 14, lot 12052.

KLEIN, HENRY (1843-1883). Private, 55th New York Infantry, Company B; 38th New York Infantry, Company K. Of German birth, he enlisted at New York City on February 10, 1862, mustered into the 55th New York that day, and transferred into the 38th New York on December 21, 1862. After the Civil War, he lived in New York City where he died of cystitis. Section 7, lot 22123.

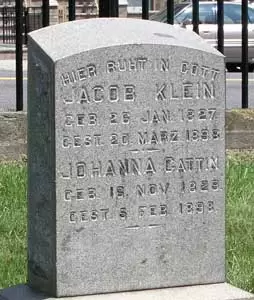

KLEIN, JACOB (1827-1898). Private, 39th New York Infantry, Company B. Originally from Germany, he enlisted as a private at New York City on May 10, 1861, mustered into the 39th on May 28, and was discharged for disability on October 30, 1862, at Chicago, Illinois. Klein last resided at 505 Third Avenue in Brooklyn. His death was caused by pleurisy. Section 143, lot 29136, grave 3.

KLEIN, JACOB B. (also known as SNYDER, JOHN) (1838-1913). Private, 48th New York Infantry, Company H. Klein, also known as John Snyder, enlisted at Brooklyn on October 21, 1863. He immediately mustered into the 48th New York, and mustered out on September 1, 1865, at Raleigh, North Carolina. Klein lived at 228 West 121st Street in Manhattan at the time of his death from pneumonia. Section 114, lot 8999.

KLENOW (or KLINOW), HENRY (or HEINRICH) (1829-1878). First lieutenant, 28th Regiment, Company K, New York State National Guard. Klenow, who was born in Germany, immigrated to the United States in 1850 from Hamburg, arriving in New York on August 16 of that year. His online family tree and the federal census show that he was living in Brooklyn as of 1860. The 1857-1862 Brooklyn Directory identifies him as a window shade manufacturer at 23 Court Street.

As per his military service card, a register of national guard officers prior to 1916, Klenow was a first lieutenant in the 28th Regiment of the New York State National Guard, as recorded by the adjutant general in 1861. That card notes that the 28th was part of Division 2 of the 5th Brigade. Soldier records show that he enlisted as a second lieutenant at Brooklyn on April 23, 1861, was commissioned into Company K of the 28th Regiment on May 11, and mustered out at Brooklyn on August 5, 1861. He was promoted to first lieutenant on June 16, 1863, returned to his regiment and company and mustered out at Brooklyn on July 22, 1863.

The 1863 and 1864 Brooklyn Directories list Klenow as a shade painter at 23 Court Street. According to the 1865 Brooklyn Directory, Klenow was still in the window shade business at 345 Fulton Street. The 1869, 1871 and 1873 Brooklyn Directories report that Klenow was a painter at 345 Fulton Street. According to the 1875 New York State census, he was living in Brooklyn with his wife and two children and was employed as a sign painter. He last lived at 231 Pacific Street in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to heart disease. Catharine (or Catherine) Offerman Klenow, his widow, is interred with him Section 115, lot 8999, grave 277.

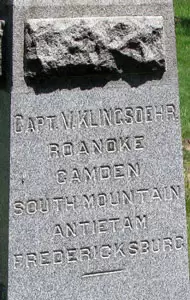

KLINGSOEHR, VICTOR (?- 1913). Captain, 9th New York Infantry, Company A. Klingsoehr is not buried at Green-Wood. His memorial at Green-Wood that lists the battles in which he served is a cenotaph; there is no record of his burial in the cemetery office. After enlisting at Brooklyn as a second lieutenant on April 23, 1861, he was commissioned into Company A of the 9th New York, known familiarly as Hawkins Zouaves, on May 4. On December 24, 1861, he rose to first lieutenant and then was promoted to captain of his company on August 10, 1862. He fought in the following battles: Roanoke, Virginia; Camden Point, Missouri; South Mountain and Antietam, Maryland; and Fredericksburg, Virginia. Klingsoehr mustered out on May 20, 1863. In 1888, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 856,738. According to his pension record, he also served in Company E of the 9th New York. Section 181, lot 10629.

KLINK, FREDERICK (1837 or 1843-1930). Private, 21st New Jersey Infantry, Company A. Klink’s birthplace and birth year are disputed by census data and cemetery records. According to the 1920 census, he was born in Pennsylvania. Green-Wood Cemetery records indicate that he was born in the United States in 1837. However, the 1870 census indicates that he was born in 1843 in Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a private on August 25, 1862, and mustered into Company A of the 21st New Jersey Infantry on September 15. He mustered out on June 19, 1863, at Trenton, New Jersey. The 1880 census states that he had a furniture store. Klink’s application for an invalid pension was approved in 1896, certificate 1,046,554. The 1920 census reports that he was a furniture salesman living on Nostrand Avenue in Brooklyn. He last lived at 86 Halsey Street in Brooklyn. His death was recorded as “genectus.” Section 119, lot 37091, grave 1.

KLOER, CHARLES J. (1844-1898). Private, 133rd Indiana Infantry, Company I. Of German birth and a resident of Vigo County, Indiana, Kloer enlisted as a private on May 17, 1864. On that date, he mustered into the 133rd Indiana, and mustered out of service on September 5, 1864, at Indianapolis. In 1885, he applied for and received an invalid pension, certificate 951,573. His last residence was 63 Clifton Place in Brooklyn. Matilda Kloer, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension after his death from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1898, certificate 502,944. Section 135, lot 34967.

KNAPP, GEORGE F. (1843-1912). Rank unknown, 13th Regiment, New York State Militia. According to his obituary in The New York Times, Knapp, who was born in Pennsylvania, served in the 13th New York State Militia during the Civil War. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was a member of the Veterans’ Association of the 13th Regiment; his comrades were invited to attend his funeral. No further details are available related to his military service. He last lived at 109 Kingston Avenue in Brooklyn. His death was caused by heart disease. Section 194, lot 29221, grave 2.

KNAPP, JAMES EDGAR (1846-1894). Coal handler, United States Navy. A New Yorker by birth, Knapp served on the USS North Carolina from April 7 to April 16, 1864, on the USS San Jacinto from April, 1864 to February 14, 1865, and on the USS Proteus from April 11, 1865 until his discharge from the USS Kineo on May 5, 1865. A manufacturer in civilian life, he last resided at 641 Palisade Avenue in Jersey City, New Jersey. He died on November 11, 1894, of locomotor ataxia and was interred at the present location at Green-Wood on May 23, 1895. Mary Knapp received a widow’s pension from the Navy after his death. Section 204, lot 29052.

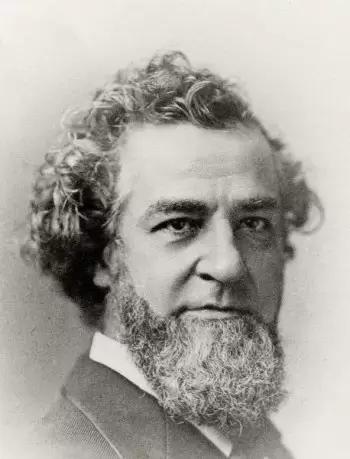

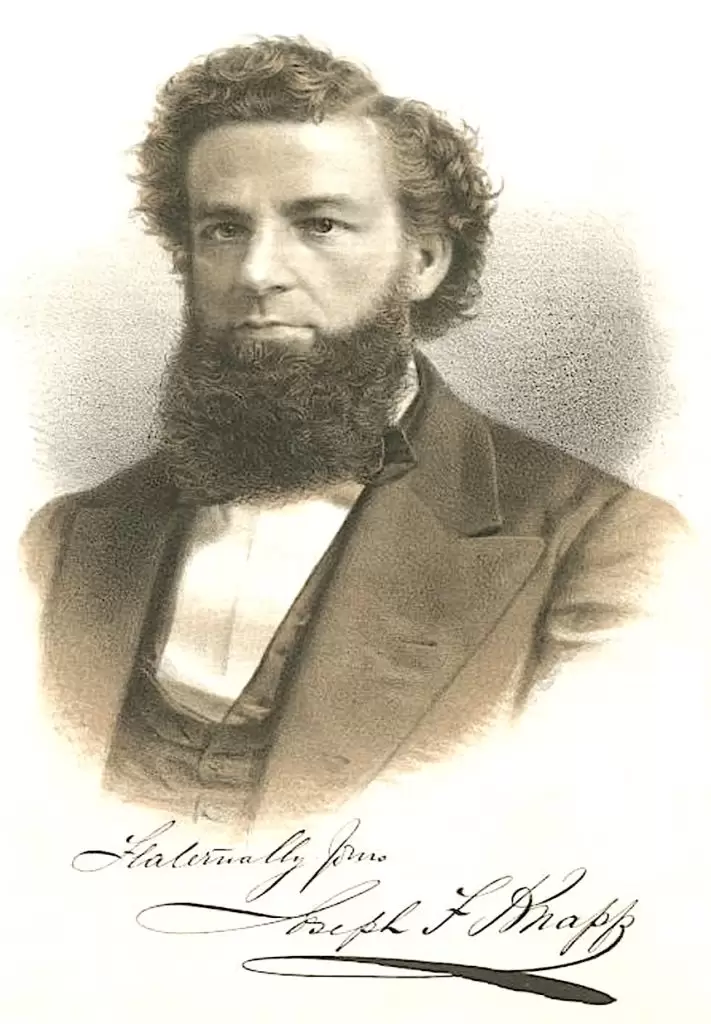

KNAPP, JOSEPH FAIRCHILD (1832-1891). Businessman. At age 16, Knapp, who was born in New York City, apprenticed as a lithographer to Frances (Fanny) Flora Bond Palmer (see), who later became Currier & Ives most prolific artist. As per an unpublished history of lithography written by the lithographer Charles Hart in 1902 and cited in Fanny Palmer: The Life and Works of a Currier & Ives Artist, by Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, Knapp learned the technique of using rubbing stuff, or tint ink, in printing to create background color. Knapp became a partner in Sarony & Major at the age of twenty-two. That establishment, a major lithographic firm, later known as Major & Knapp, made him a very wealthy man. A prominent Brooklyn businessman, Knapp lived in an elegant house on Bedford Avenue and Ross Street where he held receptions for leading artists and citizens. He began investing in and serving on the board of several insurance companies, among them Union Life.

During the Civil War, Knapp offered soldiers life and other insurances, being the first to do so. Originally called National Union Life and Limb Insurance Company in 1863, Metropolitan Life was started in 1868 to protect Union soldiers and sailors against wartime disabilities due to wounds, accidents, and sickness. He was second president of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company for twenty years from 1871-1891. According to Philip Lehpamer, who worked as an accountant for Met Life and researched Knapp’s life, Knapp’s mastery of the insurance business enabled Metropolitan Life to survive the Depression of 1873, when scores of insurance companies that started after the Civil War folded. Knapp introduced the idea of selling life insurance in small amounts and collecting weekly premiums in 1879, the same year that F. W. Woolworth introduced its 5 and 10 cent stores. According to Lehpamer, Knapp went to England where this policy was practiced and induced 544 men and their families to immigrate to the United States, eventually selling record numbers of policies from 1880-1885. Although the company experienced some financial difficulties from 1883 to 1886 during its expansion, Knapp put in over $650,000 of his own money and by 1891 the company was financially strong. In addition, he recognized talented employees and nurtured them as they attained leadership positions at Metropolitan Life.

He was honorably mentioned in the History of the Ulysses S. Grant Post #327 for his commitment to veterans and to the Grand Army of the Republic. Though he was encouraged to run for mayor and comptroller of Brooklyn, and the State Legislature, he declined to do so. Before he died, Knapp purchased the land where the MetLife building was erected in 1909 at Madison Avenue and East 23rd Street, at the time the tallest building in the world at 700 feet. A philanthropist with an interest in the arts and music, he last lived at 554 Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn where he and his wife hosted five presidents: Grant, Garfield, Arthur, Cleveland, and Benjamin Harrison. (Harrison spent Memorial Day of 1889 at Knapp’s house.) He died aboard a steamer, La Champagne, after spending time in Europe to restore his health. His son was the head of the lithography business at the time of his father’s death. It is interesting to note that his wife, Phoebe, who is interred with him, is credited with writing over 500 hymns, including the enduring “Blessed Assurance.” Section 176, lot 27752.

KNAPP, WILLIAM A. (1841-1927). Private, 70th New York Infantry, Company K. Knapp enlisted at Newark, New Jersey, on April 20, 1861, and mustered into the 70th New York on June 21. On July 2, 1863, he was wounded at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and was later discharged for disability on June 24, 1864, at Newark, New Jersey. He last resided on West 109th Street in Manhattan. Knapp succumbed to heart disease. Section 153, lot 20496.

KNAUSE, BENJAMIN FRANKLIN (or FRANK B.) (1843-1914). Private, 6th Michigan Infantry, Company E. According to his obituary, Knause was born in Waterloo, New York; however, the 1870 census states that he was originally from Michigan. During the Civil War, he was a resident of Calhoun County, Michigan, when he enlisted as a private on July 1, 1861, at Fort Wayne, Michigan. He mustered into the 6th Michigan, also known as the Wolverine Rifle Rangers, on August 20. In this exchange of letters, Knause tells his family how a comrade was killed accidentally and the response of his fellow soldiers.

Holyoke November 24, 1861

Dear Brother Frank,

What on earth is the matter with your pen. I have written over a week ago to you and no answer yet. I feel uneasy about you. Don’t delay to answer this immediately. I fear you have been sick. If I don’t hear from you by next Saturday, I shall write to the Capt. of your company.

I am going into business for myself with one of the best workmen I ever met with. Think we shall meet with success. Our folks are all well as far as I can learn.

Yours in haste. From your affectionate brother, — John W. Knause, Holyoke, Mass.

Baltimore, Md. December 1861

Dear Sisters, Libbie & Lou,

I received your kind letter and was (as usual) tickled almost to death to hear from you & I will answer your anxious inquiries. Relating to my cough, the first thing, my cough died a natural death without the help of Doctor or medicine & I am now as tough & healthy as I could wish to be. I eat all of the rations that Uncle Sam allows and sometimes wish for more. I have just returned from a three weeks tramp up on the Peninsula & I will try and give you a graphic description of all that I have seen & done.

Four weeks ago next Thursday we received marching orders and the following day (Friday) we started at 7 P.M. on the steamer Georgia for — we did not know where. It was a dismal, wet, rainy night but our company had comfortable quarters aboard of the boat. We went down the Chesapeake till we come to a place called the Muds and there we entered the Pokomoke river. The boat run up this river about 50 miles to a little town called Newtown & there we landed. We were in camp at Newtown till Sunday morning when we struck our tents and marched all day. We marched 15 miles that day, took one Rebel Battery without shooting a single gun, & encamped at Oak Hall. There we met with a sad accident.

One of the men that was on guard went to pick up his gun & in picking the gun up, it went off and killed another man in Co. H. His name was Allen Baer. The ball entered his neck just below the ear & cut the jugular vein. It killed him instantly.This cast a sad gloom over the camp. The next day he was buried — the whole regiment went to his funeral. Poor fellow. He is buried far, far from friends & home. He had a brother in Co. H & his brother felt awfully about his death.

Capt. [Smith W.] Fowler was searching for arms & ammunition in a secesh house & the lady of the house opposed him. Says she to him, “Sir, I’m a Lady of Virginia, I would have you to know, & I am for Jeff Davis.” Fowler replied sarcastically, “Madam, I am a gentleman of the U. S. of A. & I am for Abe Lincoln & I am going to search this house” & he searched and found a Rebel Capt, concealed in the garret & he took the Virginia Lady’s husband a prisoner & made him swear allegiance to the U. S. Wasn’t that rich? From Oak Hall we marched to Drummondtown — 23 miles in one day. This time we took two batteries without fighting.

In this letter, Knause discusses his family and his hope for more correspondence. He is also grateful for the water tumbler that he received as a gift.

Baltimore [Maryland]

January 9, 1862

Dear Father,

I received your kind letter today and I was glad to hear from you. I thought you had quite forgotten me, it was so long before I received an answer to my letter. Please write oftener to me. We have not received any pay yet, and when we do get paid, I am going to send what I can spare to [brother] John. He wrote to me to send him all I could spare. He says he has got to raise some money & I think that Karstadt can wait 2 months longer without feeling it and I know that John needs the money & he shall have it — all that I can raise.

I received a letter from [sister] Mary yesterday. She and [her husband] Harlie is well. I suppose you heard that Harlie has bought out his father and gone into business for himself? Mary sent me a New Year’s present for which I am very thankful. It was a pretty Gutta Percha tumbler which shuts together. I carry it around in my pocket and when I want a drink of water, all I have to do is to take it out and pull it just as you would a telescope & drink.

I am glad you told me where [sister] Libbie is stationed for I have wanted to write to her but could not for I did not know where to direct. I suppose you got the package I sent to you with the letters. I thought I could save postage and I did not have a cent or a postage stamp. When I heard from John last, he was visiting at Frankfort. He wrote that all of the folks were well but Aunt Lucy. She was quite unwell. Uncle Lambert is keeping tavern in Frankfort. I wrote a long letter to Grandpa Wyant today. I got to thinking of him and I thought I would write. Maybe he would be pleased to hear from me. Do you remember Angeline’s husband? …. [end of letter missing]

In this letter to his sister from New Orleans in January 1863, Knause thanked her for the food gifts that he received. He described his poor health at that moment and his reflections about his family and the changing of the guard in Louisiana when Major General Benjamin F. Butler was replaced there.

Camp Dudley New Orleans, La. January 28, 1863

My Dear Sister,

The box you had the kindness to send to me I received yesterday and for the things, accept my grateful thanks. I cannot do more to pay you now but perchance the time may come when I can return in some way your kindnesses. You don’t know how much good those things are doing me. Everything (but the doughnuts in that cunning little teapot) kept nice. The doughnuts got musty. The large cake kept nicely and was not bruised a particle. And the housewife you made for me is handsome and I think a great deal of it. Mary’s peaches were splendid and the jelly, cake & cookies were tip top. The dried beef and butter are not a bit behind. The tea came very acceptable as I cannot go the coffee that they make here. The apples and popcorn made me think of home. I am very thankful for that Testament from Coz. Mary. It was just what I wanted. You don’t know how thankful I am to you all.

You see I have been so sick that I could not stomach the things they cook here. If I did eat a piece of fried pork or drink a cup of coffee, I would have to throw it up again. But now a little tea and some crackers and butter go first rate. Indeed, I thank you ever so much. But enough of this.

My health continues to grow no better very fast and sometimes I feel so weak and feeble that I can scarcely raise myself. I have got a bad cough. I caught cold and it settled on my lungs and I just cough sometimes so that I cannot sleep. I feel a good deal better today than I have felt in a good while, and I hope I will soon get well. The Doctor wanted me to go to the hospital but I did not want to go. I was afraid I would get low-spirited if I went there. As long as I can keep my spirits up, there is a prospect of my getting through. But just as soon as I allow myself to get low-spirited, why I will get down sick.

When I get so that I cannot write for myself, I will find some way of communicating the same to you immediately. But don’t worry about me till you hear that I am sick abed and in the hospital. I will write as often as once in 2 weeks to you & Mary or John. I would write oftener but it so unhandy to write here that I almost hate to write.

We were all sorry to part with our old commander, Major General Benjamin F. Butler. I think he has done better than any other General in the field. The people of New Orleans feared Old Ben but they loved him, and while he was here the citizens kept a civil tongue in their heads. Now it is different. Since the arrival of Banks, the citizens are as saucy and independent as though we were not here. When Butler was here, they did not dare to come out in the street and hurrah for “Jeff Davis.” If they did, they knew that they would go to Fort Jackson for 3 years, and that was serving them just right. I wish he was coming back to take command of the Department of the Gulf.

I got a letter from Father with his and Mother’s and the baby’s picture in it. He was getting along finely then and his health may continue good and may he enjoy many years of happiness yet on earth. I do love him so much for he has been a good and noble Father to us. When I hear some of the boys tell how they have been whipped and abused at home by a drunken Father and deprived of the privilege of going to school or to Church, I always think of what a kind Father we had and then my thoughts will wander off and sometimes grow very bitter when I think of how I repaid his love and kindness by being as ugly as sin could make me. Ah, Libbie, if I could only have those younger days to live over again with my experience. I would lead a far different life. It is with me as with a certain writer — “experience has made me a sadder but yet a wiser man” — and during the remainder of Father’s life, I shall strive to make it pleasant and render him happy as I can. “Man proposes and God disposes.”…

Knause wrote this letter to his parents from Camp Kenner in Louisiana on March 31, 1863. The property, listed on his letter as the Sherman Plantation, had formerly belonged to Duncan Ferrar Kenner, a sugar planter, politician and chief diplomat from the Confederate States of America to England and France in 1864. After the capture of New Orleans in 1862, most of Kenner’s land was confiscated and his slaves were freed.

Camp Sherman

Kenner’s Plantation March 31, 1863

My Dear Folks at Home,

Tonight I again find myself seated to write you a few lines. I have just finished a letter to Libbie and I have got one more postage stamp left and I have come to the conclusion that you want to hear from me worse than anyone else and so I am going to try and tell you how I am getting along. I am pretty well and in good spirits and seeing that I can’t get my discharge, I am going to get well and do the best that I can. I hope that you will get along all right. I am doing first rate but I must close for tonight. — Frank

[April] 1st. I had to close my letter rather abrupt last night for my candle went out and left me in the dark. Today I have been fishing but I did not catch any fish. I left the Hospital on the 29th and came up to camp. Our present encampment is located 13 miles from New Orleans at a small place called Kenner. The railroad lays on one side of our camp and the Mississippi river on the other side. The cars go to the city twice a day and boats are going up and down all the while on the river, but notwithstanding all of these things, it is very lonesome here.

All of our regiment have gone up to Manchac Bayou on an expedition (all except a few sick ones left here in camp). They have had a fight with the rebels and the latest news we got from them was rather dubious. Two companies of the 177th New York Regt. were captured by the rebels and one of our iron-clad gunboats. Our Colonel is in command of the expedition and if he don’t look out he will get captured with his whole Brigade.

Blackberries are plenty and as big as a good sized plum. We can buy a quart of them from the Niggers for a piece of bread or a piece of meat and I tell you, they do good. I wish that I could send you some for your supper, but of course that is an impossibility. Alligators are plenty and the boys go out hunting them every day. I myself have eaten a piece of alligator tail but I must confess to you that it is not a very desirable dish. Our boys killed one last week and eat him. Corn is up a foot high and Irish potatoes are as high as the corn.

We are camped in a field where the white clover is up to my knees. All the rose bushes are in blossom and in fact, it is just like summer here now. There are 5 large plantations here in a row that have been confiscated and they are now worked by free darkies and Uncle Sam pockets the profits. This is as it should be and I like to see them go into it in this style.

The Inspector General says that he is going to move the Michigan 6th Regiment down to the city of New Orleans when they come back. I for one think that it would be healthier for us all if they would keep us here in the country where we could get all of the fresh air that is stirring. Still if we go to the city, we will have good warm quarters and we will get better living and have a better chance to get our letters and to send letters home.

Give my respects to Mr. Grant’s people. I want you and Mother to write to me real often for a letter from home is a cheering thing to the poor soldier and there is no one on earth that I love to hear from so much as I love to hear from you. You must not look for a letter from me again very soon for my postage stamps are gone and I can’t say when I will get any more. We have not got our pay yet and we don’t expect it till we get our 4 months pay. I guess I will have some then to send home to you. Butter is 50 cents a pound. Eggs 75 cts. per dozen. Cheese 30 cents a pound. Potatoes 8 cents a pound. Apples 5 cents apiece and every thing accordingly.

Well as it is getting late I will close. Give my love to all with a good share for ourself and Mother and little sister Carrie. You must write to me as often as you can. Tell Frank Sweet that I have written twice to him and he has not answered me. My love to you & Mother. Kiss little sister Carrie for me and please do write to your affectionate son, — Frank B. Knause

On June 8, 1863, Knause wrote to his sister from Baton Rouge, Louisiana:

My Dear Sister Libbie,

Your kind letter with Mary’s enclosed came duly to hand, and I was very glad to hear from you once more. I am still at Baton Rouge — not very well — but in the best of spirits. Our regiment is at Port Hudson fighting Rebels but I don’t think they will stay there much longer. I think Port Hudson will fall long before you get this letter and then I think all of the Western Regiments in this Department will join Gen. Grant’s Army leaving the Department of the Gulf for General Banks and his Eastern men to take care of it.

There is nothing to be seen in Baton Rouge but sick and wounded soldiers and paroled Rebels. I hope this war won’t last much longer for I want to come home. Won’t we have such fun? You & Louise & Frank Sweet & Frank Knause. We will have our boating parties, hunting, fishing &c. etc.

I don’t know but I think I would like to go North of Marshall 20 or 30 miles and buy me a place and build a nice house and settle down near to Father. You know he is getting old and will need someone to take care of him in his old age. We must always help one another and try to do as we would be done by. I feel as though I would get through this war all right and get home all right and if I do, what a great benefit it will be to me. Now since I have been out into the world and learned to think unselfishly, I can see many places in my life where I have done very wrong, and I find upon sober reflection that in many places where I have blamed others for doing wrong, it was me that done the wrong. The more I think of my past life, the more fault I have to find with myself. I have done wrong all my life and now while I live, I must try to rectify my many faults. I have read my Testament most through and when I finish that, then I shall take the whole Bible and study it. I think every man had ought to study the Bible and live as near right as he can and not pick it to pieces to patch up a doctrine that will suit him. I believe in the whole Bible though there is some parts that I can’t understand and I believe that those parts which we can’t understand were not made for us to quarrel about. But enough sermonizing.

Baton Rouge is not so healthy as it used to be last year. The Small Pox has made its appearance here but I think the doctors will get that stopped. I don’t fear it much for I have been vaccinated. There is not much fever here and I guess we will have a pretty healthy summer if nothing happens.

You talk just as though you thought I was crazy to get married but you don’t know Frank Knause if you think he is anxious to get married. Why how in the world could I get married? I have no way to support a wife and then again, even if I had a way to support a wife, I know of no one who would suit me. I like Jennie Beecher very well (or at least I used to) but she is too much of a doll and then she is too gay to mate with a person of my moody disposition. Such a woman as I would have — one who would make me happy — would have to be possessed of the following qualities. She would have to be amiable (no scolding allowed), Lady-like, gentle (not tame, a little spirited), a good singer, well educated (not a regular blue), neat in person and about the house. A good cook and a smart worker. Always happy (one that don’t know what the blues are) and a good Christian &c, &c.

You see I would be hard to suit and you can make up your mind that Frank Knause, like his illustrious brother John W., would be glad to get married if he could ever find one who suited his taste exactly. But he may live until he is 40 years old before he can find such an one. And when I do find one of that kind, I will immediately begin the siege and if she ever surrenders to me, I will invite all of my friends up to see me spliced. Don’t fear for me Libbie. I will let you know always in good time and listen to any suggestions you may make and we will drop the subject of marriage till next time.