GIBBES, EDMUND A. (1819-1876). Surgeon, Confederate States Medical Staff; acting assistant surgeon, General and Staff Officers Corps, Confederate States of America. Gibbes was a native of Charleston, South Carolina. When his attorney applied in 1844 for a passport for Gibbes to travel to Europe for two years, he described him as 5′ 8″ tall with light hair and eyes, a nose “rather inclined to the Grecian form,” with a pale complexion and “general appearance delicate.” According to Three Rivers Form an Ocean…Vignettes of Life in Charleston, SC, by James Funk (2003), Emma Holmes wrote in her diary on October 14, 1861, that the government sequestered the property that belonged to Edmund Gibbes for “refusing to do military service, or pay his fine” and that “…his only good point was that he loved his mother.”

Civil War Bio Search

The 1861 census for Charleston showed that he owned three properties on John Street in the 5th Ward that were occupied, one only by slaves and the others by slaves and free persons. He also owned two properties on Wall Street in Charleston. Other documents note that he desired to obtain $16,000 in funds that he had in New York in 1861. On November 21, 1861, he was in custody of the marshal of the CSA, South Carolina, accused of taking an oath of allegiance to the United States. The next day, he wrote a statement claiming that he had visited New York City after the Civil War began in order to collect a $16,000 debt. He insisted that he was loyal to the Confederacy and denied any oath of allegiance to the Union. To support that statement, he said that in the spring of 1861 he bought $6,000 of Confederate stock, $5,000 of state bonds for the War, and that his real and personal property in South Carolina was worth more than $300,000. He also attested that he was willing to take an oath of allegiance to South Carolina.

Subsequently, Gibbes was an acting assistant surgeon, in the General and Staff Officers Corps, serving in the Number 4 General Hospital at Wilmington, North Carolina, for November 1864, after receiving an appointment on June 6, 1864. As of February 1865, he was assigned to the General Hospital in Wake Forest, North Carolina. Then, Gibbes was a surgeon for the Confederate States Medical Staff. On March 9, 1866, Doctor Gibbes wrote this letter to Lieutenant Jesse Craig of the 35th U.S.C.T. outlining his contract with five freedmen from his plantation in Charleston, South Carolina:

Dear Sir,

Your letter of March 3rd requesting information regarding my plantation near Adam’s Run, &c has been received & in reply I would state, that the lands, premises, & c are leased for one year from Jan 1st 1866 to Samuel Gibbes, Sampson Fenwick, Gainey Singleton, Ancel Guerard & Harry Rivers; Freedmen formerly belonging to me. The terms are Five Bushels of produce to each acre of high land planted to be delivered to me as soon as harvested. I furnish nothing, & have no control over their actions whatever, they being at liberty to contract for labor with who they think proper, irrespective of former owners, & are amenable to the laws, as we all are. I have but little faith in written contracts, as they offer no more security than a verbal understanding between parties disposed to be just, hence this is a verbal contract between persons, who have known each other all their lives, but it was understood, that if the law required one, it must be at their expense. This contract was made as early as the first November 1865, with a reservation on my part, that if the landholders came to any determination, as to what course they would pursue, that I would feel myself bound to c??? with them, but as no such plan was followed, but each has entered upon his own course, I then concluded definitely(?) the terms here named on the 1st January 1866.

I have been repeatedly invited by them to visit the place, but in consequence of the absence of all comforts, I have not ???? done so, but I now contemplate going up there on Saturday by railroad to Edisto River, & by boat to the plantation, where I shall remain until Tuesday & return, I have no mode of conveyance to Adams Run, but if you will call on the place will be happy to see & confer further with you on Monday.

I remain Yours very Respectfully,

E.A. Gibbes

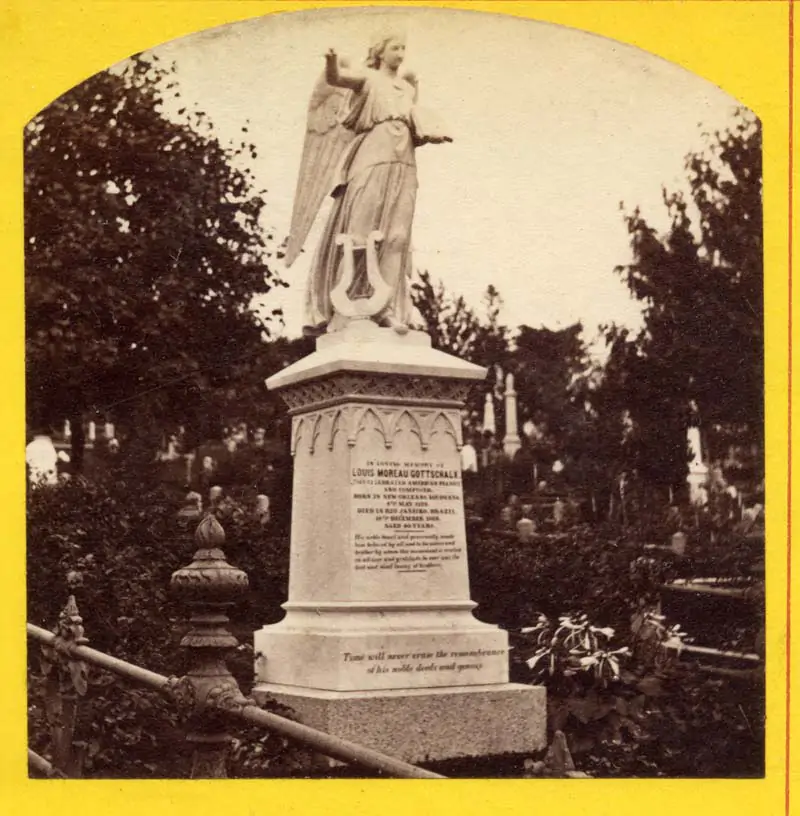

He last lived at 50 Navy Street in Brooklyn. He died of stomach cancer. Section 186, lot 18533.

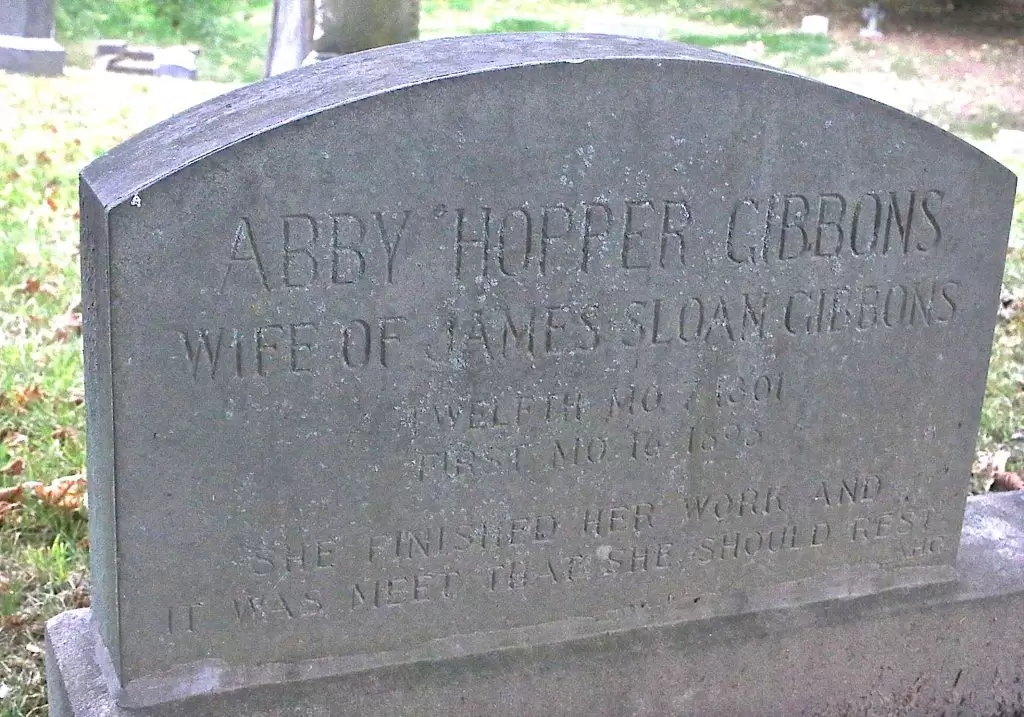

GIBBONS, ABIGAIL HOPPER (1801-1893). Antislavery and prison reformer and Civil War nurse. Gibbons was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Quakers Sarah and Isaac Tatem Hopper (see), educated at home and in Quaker day schools, and reared in an atmosphere in which devotion to good works was a daily concern. In 1821, she established a school for Quaker children in her native city, and ran it for the next decade. She joined her father in New York City in 1830, married James Sloan Gibbons, a Philadelphia Quaker, in 1833, and settled in New York City. Together with her husband, she became an important worker in the Manhattan Anti-Slavery Society, and their house became a haven for escaping slaves. She organized fairs to raise money for abolitionism. When her father and husband were disowned by the Meeting of Friends for their anti-slavery activism, she read her own resignation from the society at its yearly meeting.

She devoted herself to other causes including temperance, aid to the poor, opposition to capital punishment, and the rehabilitation of prisoners. A leader of the Prison Association’s Female Department, she was on the managing committee of the Isaac T. Hopper Home (which offered lodging to women just discharged from prison), and was an important member (and later head) of the Women’s Prison Association and Home. In 1855, when her son’s death at Harvard caused her such depression that she feared she might become insane, she mustered even greater energy to help others. She did welfare work in New York’s tenements, visited prisoners at the Tombs every week, and worked at the Randall’s Island Infant Asylum. In 1859, she was named president of the German Industrial School.

When the Civil War began, she and her daughter Sarah went to Washington, D.C., and worked as nurses for the next three and a half years. At the hospitals, principally the Patent Office Hospital, she and her daughter distributed supplies to the soldiers that were provided by friends and from the Woman’s Central Association of Relief, an organization that was most active in New York. On a visit to a hospital in Fall’s Church, she was implored by a volunteer recruit from Penn Yan, New York, to stay and help. The sight of the emaciated soldier remained with her and she took a room in a nearby saloon for $5 a week and tended to 39 sick men who were most in need. Six weeks later, they were restored to health, including the man from Penn Yan, according to L. P. Brockett, M.D., and Mary C. Vaughan in Woman’s Work in the Civil War (originally published in 1867, page 469). She then traveled to Seminary Hospital where the severely wounded were housed and later was at Strasburg, Virginia, when the enemy took over the facility and the nurses and patients were forced to flee. Gibbons was at Point Lookout, Maryland, when Hammond United States General Hospital opened in July 1862. During her fifteen months there, she and her daughter nursed soldiers who were traumatized by War, barely able to walk, dirty, and malnourished.

During her service she advocated for Negro contrabands and criticized the “ignorant butchery” of army surgeons. Some army officers resented this criticism, but she was protected from retribution by Senators and other prominent officials. She was not so lucky with the mob that sacked her New York home during the Draft Riots of July 1863. Brockett wrote that all the window panes of her house were broken, the furniture destroyed, contents of drawers stolen or ruined, carpets were soaked with water and mud, and her piano burned. Papers and memorabilia from her father and late son were also defaced (pp. 473-474). After a stay in New York, Gibbons and her newly-widowed daughter returned to their work as nurses after the Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia, in May 1864. Shortly thereafter, they opened a make-shift hospital at Fredericksburg, Virginia, readied beds that they filled with straw and prepared food for the sick and injured. Eventually, they accompanied and ministered to the soldiers when Fredericksburg was evacuated. After stays in White House and City Point, Virginia, the two women accepted appointments at a hospital in Beverly, New Jersey, that housed 1,900 patients, and required long hours and arduous labor.

After the War, Gibbons organized the Labor and Aid Society to help veterans find work, and established laundries and nurseries to provide work and help for the widows and orphans of the Union dead. She was a founder in 1873 of the New York Diet Kitchen Association which gave food to the sick who could not otherwise afford it. In her capacity as head of the New York Committee for the Prevention of State Regulation of Vice, she opposed bills in the State Legislature that would have mandated the licensing and examination of prostitutes. She successfully championed a bill which in 1890 created the position of police matron, allowing women to be searched for the first time by female officers. Her greatest achievement, she believed, was the creation of a women’s reformatory in New York City. Elizabeth Cady Stanton said of her, “Though early married, and the mother of several children, her life has been one of constant activity and self-denial for the public good.” Gibbons died from pneumonia. Section 31, lot 5805.

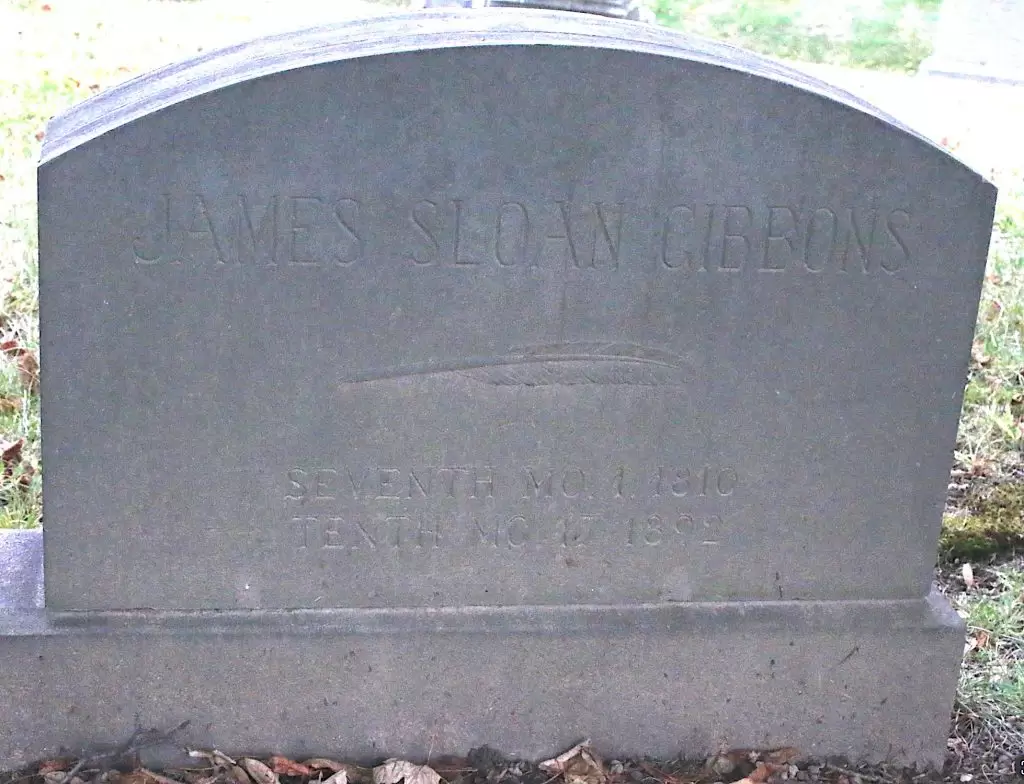

GIBBONS, JAMES SLOAN (1810-1892). Abolitionist and Abigail Hopper Gibbons’s husband. A Quaker abolitionist who had “a reasonable leaning toward wrath in cases of emergency, he wrote a popular recruiting poem that was set to music by Stephen Foster, Luther O. Emerson, and others, “We are Coming, Father Abraham, Three Hundred Thousand More.” His death was due to a hemorrhage. Section 31, lot 5805.

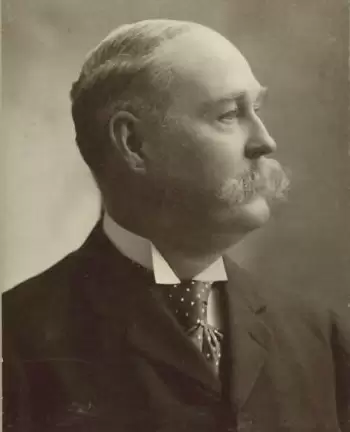

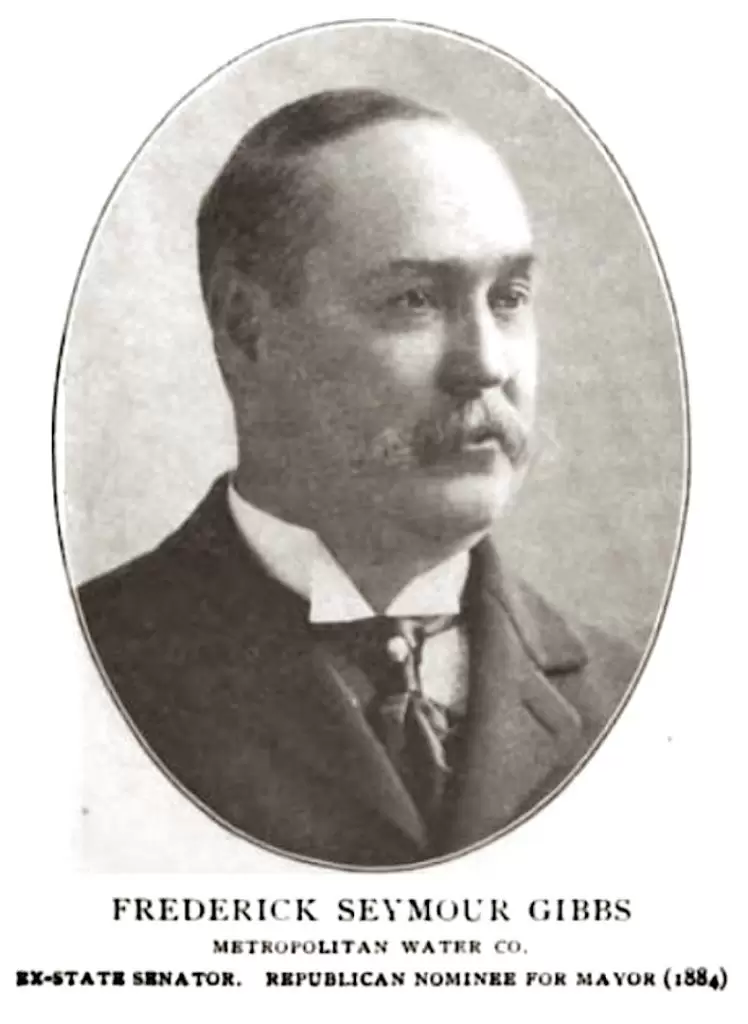

GIBBS, FREDERICK SEYMOUR (1845-1903). First lieutenant by brevet; second lieutenant, 148th New York Infantry, Company A. Gibbs, who was born in New York State, enlisted on July 30, 1862, at Seneca Falls, New York, as a private. On August 8, 1862, he mustered into Company A of the 148th New York, a regiment raised chiefly in Geneva, New York. He became corporal the next month on September 14, and was promoted to sergeant on January 1, 1864. He was wounded in the face on June 3, 1864, at the Battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia. (Later, he grew a heavy moustache to conceal the scar.) Subsequently, he was promoted to sergeant major and transferred into the Field and Staff on March 2, 1865. On April 2, 1865, he was wounded in the leg by a shell at Petersburg, Virginia. He rose to second lieutenant on June 9, 1865, but did not muster in at that rank. Gibbs mustered out on June 22, 1865, at Richmond, Virginia, and returned to Seneca, New York. According to his obituary in The New York Times, he was brevetted to first lieutenant for “gallant and meritorious services.”

In civilian life, Gibbs worked for the Gould Pump Company in Seneca, then came to New York City as that company’s representative. His application for an invalid pension was granted in 1880, certificate 227,252. Active in the Republican Party, he ran for mayor of New York City against William R. Grace, in 1884, while he was a member of the New York State Senate, having won election to that legislative body in 1883 where he was chairman of the Committee on Cities. After losing the mayoralty election, he returned to the State Senate representing the 8th District from 1884-85, then represented the 13th District from 1889-90. A member of the Republican National Committee from New York from 1896 through 1903, he was a delegate to the Republican National Convention from New York in 1900, supporting William McKinley. An art collector, he was the president of the Metropolitan Water Company at the time of his death. Among the civic organizations to which he belonged were the New York Republican Club, the New York Athletic Club, and the Salamander Club. Gibbs last lived at 421 West 22nd Street in Manhattan but died in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Daisy Gibbs, his wife, applied for a widow’s pension in 1903, application 794,631, but there is no certificate number. An application for a minor’s pension in 1913 was approved under certificate 566,298. Section 153, lot 20154, graves 12 and 13.

GIBBS, JAMES (1835-1866). Private, 84th New York (14th Brooklyn) Infantry, Company A; 6th Veteran Reserve Corps, Company G. Of English birth, Gibbs enlisted as a private at Brooklyn on September 3, 1862, mustered into the 14th Brooklyn seven days later, and was wounded at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1863. He transferred into the 6th Veterans on March 16, 1864, from which he was discharged. His last residence was on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to cholera. Section B, lot 11005, grave 112.

GIBERSON, CHARLES H. (1838-1879). Lieutenant and surgeon, United States Navy. Originally from Bath in New Brunswick, Canada, Giberson studied medicine in Fredericton, New Brunswick, and then was a graduate of the Medical College at Burlington, Vermont, from which he graduated with high honors. During the Civil War, he was a New York City resident who was a house doctor at Island Hospital at Blackwell’s Island, New York City, as of July 24, 1861. Subsequently, he was appointed by the Naval Medical Board and served on the USS Susquehanna as an assistant surgeon with the rank of lieutenant in 1862. As per his obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, he was a surgeon on the USS Tennessee and the USS Mississippi where he was attached when the latter vessel captured New Orleans, and then when that ship burned at Port Hudson, Louisiana. He was promoted to surgeon on May 1, 1865.

After the Civil War, Giberson sailed to South America on one of the War vessels and then became a surgeon at the Naval Hospital. After resigning his commission in 1868, he practiced medicine in Brooklyn, built a large practice and gained renown as a surgeon. He was loved and respected by colleagues and patients. A Freemason, he was active in many medical societies including the King’s County Medical Society, Physicians’ Mutual Aid Association, New York Medical Historical Society, and the Brooklyn Pathological Society (of which he was a founding member in 1870 and its secretary and treasurer). An attending surgeon at the Brooklyn City Hospital, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that he completed his rounds despite a severe headache a few days before he took sick with peritonitis, which ultimately caused his death. Giberson last lived at 98 Remsen Street in Brooklyn. His funeral took place at the Reverend Dr. Storr’s Church of which he was a member. He was survived by his wife and four daughters. One of his daughters, Indiana Gyberson, who took her mother’s first name, changed the spelling of her surname and who is interred with him, was a painter who first showed her work at the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1920s. Section 141, lot 23029.

GIBERSON, SAMUEL (1834-1914). Captain, 42nd New York Infantry, Companies I, D, and A; private, 7th Regiment, New York State Militia, Company I. Born in Tom’s River, New Jersey, and a ship carpenter by trade, Giberson enlisted at New York City on April 19, 1861, to serve 30 days. He mustered into the 7th Regiment as a private, and mustered out with his company on June 3, 1861, at New York City. He re-enlisted at New York City as a second lieutenant on May 12, 1861, and mustered into Company I of the 42nd New York on July 6, 1861. On August 23, 1861, he wrote to his mother that he intended to be home for turkey and all the trimmings of New Year’s Day. He noted, “I will be home to eat dinner with you.” He was promoted to first lieutenant (not commissioned) and transferred to Company D on September 13, 1861, then transferred to Company A six days later. On October 21, 1861, he was captured in action at Ball’s Bluff, Virginia, and was promoted to captain the next day. His exact date of parole is not stated. However, he did not spend New Year’s Day with his mother; he was in fact incarcerated at Richmond Virginia’s Liggon Tobacco Factory which had been converted into a prison for Union captives. After his release, he returned to his company as its captain. He was discharged on September 28, 1862. The 1863 Draft Registration lists him as a ship carpenter.

On November 7, 1870, an article to voters of the Twentieth Ward appeared in the Brooklyn Standard Union in support of Giberson’s campaign to be alderman from the Republican Party. That piece, written by ex-collector A. M. Wood, notes that Giberson, his deputy collector of internal revenue for the Second District, was efficient, honest and well-qualified to represent the taxpayers. The two first became acquainted while they were prisoners of war in Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, in 1861. The censuses of 1880, 1900, and 1910 indicate that he was a customs inspector. On October 17, 1884, he mustered into Edward Wade Post #520 of the G.A.R. He applied for and was granted a pension in 1908, certificate 1,057,571. Giberson was a member of the Seventh Regiment War Veterans Association. His obituaries in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the Brooklyn Standard Union confirm his Civil War Service, promotion for bravery, and confinement in Libby Prison. At the time of his death from pneumonia, he was residing at 397 Adelphi Street, Brooklyn. Elizabeth Giberson applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1914, certificate 788,346. Section 33, lot 5519.

GIBSON, ARCHIBALD (1846-1881). Captain, 73rd New York Infantry, Companies I and C. Of Scottish birth, he enlisted at New York City as a first lieutenant on May 3, 1861, and was commissioned into the 73rd New York on August 2. He was promoted to captain on November 10, 1861, effective upon his transfer that day to Company C, and was discharged on June 3, 1863. As per the 1880 census, he was a carpet printer. He last lived at 551 West 51st Street in Manhattan. He died of phthisis. Section 15, lot 17263, grave 1486.

GIBSON, DEWITT J. (1843-1909). Private, 72nd New York Infantry, Company G; 120th New York Infantry, Company I; 73rd New York Infantry, Company G. Gibson was born in Warwick, New York, on November 23, 1843, to David and Elizabeth Gibson. At the time of his birth, he was the youngest of three siblings, including Mary R. Gibson and William H. Gibson. The 1850 federal census locates him in Chester, New York, at age seven with his parents, Mary (12), William (8), and younger siblings Anson (5) and Emily 2.

While an 18-year-old farm laborer, Gibson enlisted on July 17, 1861, and mustered into the 72nd New York Infantry, Company G, in Chester on July 28. On his muster roll, he was described as having gray eyes, dark hair, and light complexion. That muster roll also notes that he was wounded in action in Fredericksburg, Virginia, on December 13, 1862. On December 20, 1863, at the age of 20, he re-enlisted into Company G before again being wounded (no date or location recorded). On July 24, 1864, he transferred into the 120th New York Infantry, Company I. Just short of a year later, on June 1, 1865, he transferred out of the 120th and into 73rd New York Infantry, Company G, where he finished his military service. On July 24, 1865, Gibson mustered out at Washington, D.C. According to the 1865 New York State census, he, at age 22, returned to his parents’ home in Chester.

His pension index card confirms his service in the 72nd, 73rd, and 120th Infantries He applied for an invalid pension in 1871; it was approved, certificate 114,514.

Per Ancestry.com, Gibson married Elizabeth Morgan (1845-1911) in 1867. The 1870 federal census indicates that they lived in Blooming Grove, New York, with two children: Dewitt Jr. (3 years old) and older sibling Melvina (age not given). In the census, Gibson is identified as a 26-year-old farm laborer.

The New York State census of 1875 identifies Gibson as head of household of a residence in Chester with wife Elizabeth, and two additional sons: Eugene A Gibson (5) and Edmond Gibson (1). In 1880 at age 35, DeWitt moved his family to Middletown, New York.

In 1900 federal census lists DeWitt (60), Elizabeth Gibson (59) and their children as living at 249 59th Street in Brooklyn, in the home of his daughter Melvina Moyle (30), who was now married to J. Samuel Moyle (married for three years) with their three children.

Gibson’s last residence was 523 59th Street, Brooklyn, State Hospital Boro of Brooklyn, where he died on April 14, 1909, at the age of 65. The cause of death was “mental disease.”

On May 7, 1909, his widow, Elizabeth Gibson, applied for and received a widow’s pension, certificate 685,438. She died in 1911 and is interred in the lot with him. Lot 27263, grave 2253.

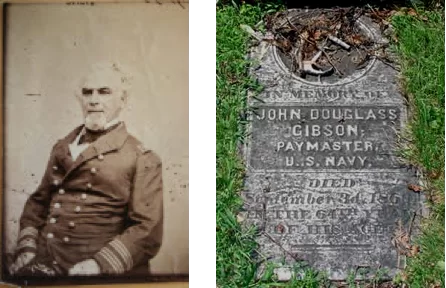

GIBSON, JOHN DOUGLASS (1803-1869). Purser, United States Navy. Gibson enrolled in the Navy as a purser on June 4, 1840, and served until his retirement on December 10, 1867. He last lived at 156 Union Street in Brooklyn. He died from cirrhosis of the liver. Section 171, lot 9218.

GIBSON, ROBERT (1847-1895) Musician, 79th New York Infantry, Company C. A native of New York State, he enlisted at New York City on May 13, 1861, as a musician, and mustered into the 79th New York on May 28. He was discharged for disability on March 26, 1863, at Annapolis, Maryland. As per the census of 1880, he was a skate manufacturer. He joined G.A.R. Post #170, the Addison Farnsworth Post, on September 2, 1892. His last address was in Yonkers, New York. His death was attributed to miliary tuberculosis. Section 52, lot 4344, grave 3.

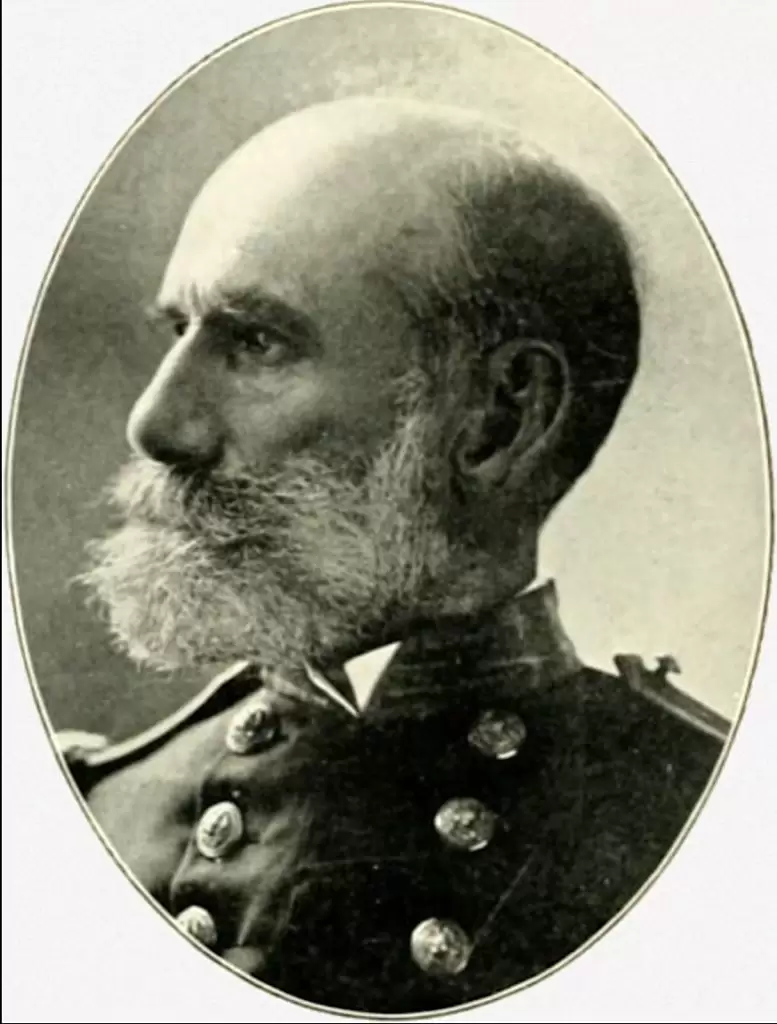

GIBSON, WILLIAM CAMPBELL (1838-1911). Rear admiral, United States Navy. Born in Albany, New York, he entered volunteer service in the Navy on December 15, 1862, and rose through the ranks. During the Civil War, he served in the Potomac flotilla and in the North and South Atlantic Blockading Squadrons. After the War, he was promoted to ensign on March 12, 1868, to master on December 18, 1868, to lieutenant on March 21, 1870, and to lieutenant commander on July 13, 1884. As per his obituary in the New York Herald, he had the distinction of taking the USS Monongahela from San Francisco to New York in 106 days in 1890. Gibson was promoted to commander on July 4, 1893. He was stationed at the Portsmouth Navy Yard in New Hampshire, then was commanding officer of the training ship Adams in the Pacific. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, he was detailed to the City of Peking which brought men to Manila in the Philippines. From October 1898 to February 1890, he was senior member of the board of inspection at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Gibson rose to captain on February 18, 1900, then commanded the USS Texas in the waters off Bermuda. The Utica Herald-Dispatch of May 23, 1900, reported that an incident aboard the Texas, first thought to be a mutiny, occurred when enlisted men, somewhat drunk after returning from shore leave, were given rum to mix with varnish in order to shellac the decks. Allegedly, lemon juice and sugar were added to the concoction which was then drunk. A crazed melee ensued, marines were called in to quell the disturbance, and the participants were put in chains. Captain Gibson denied the mutiny rumors and court-martials were expected when the ship docked in New York; the results of the court-martial are not known. Gibson retired on July 23, 1900, with the rank of rear admiral. He last lived at 1412 Pacific Street in Brooklyn. Section 200, lot 24115, grave 5.

GIERLOFF, JOHN H. (1825-1895). Seaman, United States Navy. Of German birth, Gierloff enlisted on June 30, 1861, at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He served on the USS North Carolina from September through October 12, 1861; the USS Niagara to November 15, 1861; the USS Massachusetts to January 1, 1862; and the USS Colorado from which he was discharged on June 30, 1862. His pension application was granted under certificate 10,523.

Gierloff became a naturalized citizen on October 17, 1876. As per the New York City Directory of 1877, he was a watchman. He last lived at 192 4th Street in Jersey City, New Jersey. A military stone was requested in 1895 and ordered from the Vermont Marble Company. His widow, Catherine Gierloff, who is interred with him, received a pension from the Navy shortly after his death from cardiac rheumatism in 1895, certificate 14,949. Section 135, lot 27263, grave 691.

GIFFIN (or GRIFFIN), HENRY C. (1845-1892). Private, 83rd New York Infantry, Company H. Giffin was born in New York. As per the 1860 census, he was a gas fitter apprentice. During the Civil War, Giffin enlisted as a private at New York City on May 27, 1861, mustered into the 83rd New York that same day, and deserted on December 13, 1862, at Fredericksburg, Virginia.

The 1875 New York City Directory reports that he was a police officer living at 228 West 16th Street in New York City. The 1880 census and the 1886 New York City Directory report that he was a gas fitter; he was living at 458 West 29th Street in New York City in 1886. He last lived at 452 West 31st Street in Manhattan. He died from phthisis (tuberculosis). Although Lillie Giffin applied for a widow’s pension, application 801,402, there is no certificate number. Section 135, lot 27263, grave 2142.

GIFFORD, SAMUEL E. (1842-1904). Sergeant, 173rd New York Infantry, Company A. Born in Brooklyn, he enlisted there as a private on September 5, 1862, and mustered into the 173rd New York on October 30. As per his muster roll, he was a carpenter by trade who was 5′ 6¼” tall with green eyes, black hair and a dark complexion. He was promoted to sergeant on August 10, 1864, and mustered out on October 18, 1865, at Savannah, Georgia. The census of 1880 and the Brooklyn Directory for 1889 list him as a house carpenter. His last address was 99 12th Street in Brooklyn. Gifford died of pneumonia. Section 85, lot 1595, grave 112.

GILBERT, ARTHUR WASHINGTON (1839-1916). Private, 24th Wisconsin Infantry, Company B. A resident of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Gilbert enlisted on August 21, 1862, mustered into Company B of the 24th Wisconsin Infantry that same day, and was discharged for disability on December 17, 1862. The Brooklyn Directory for 1874 reports that Gilbert was a bookkeeper who lived at 92 Ryerson Street; the 1897 Brooklyn Directory reports that he was a superintendent who lived at 64 Downing Street. In 1901, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 1,033,792. The 1890 Veterans Census and his obituary in The New York Times confirm his service in the Civil War. He last lived at 271 9th Street in Brooklyn. Section 116, lot 4073.

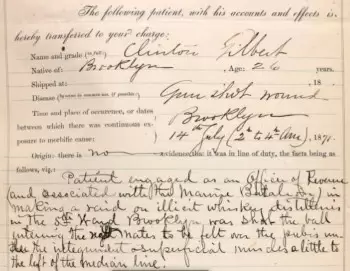

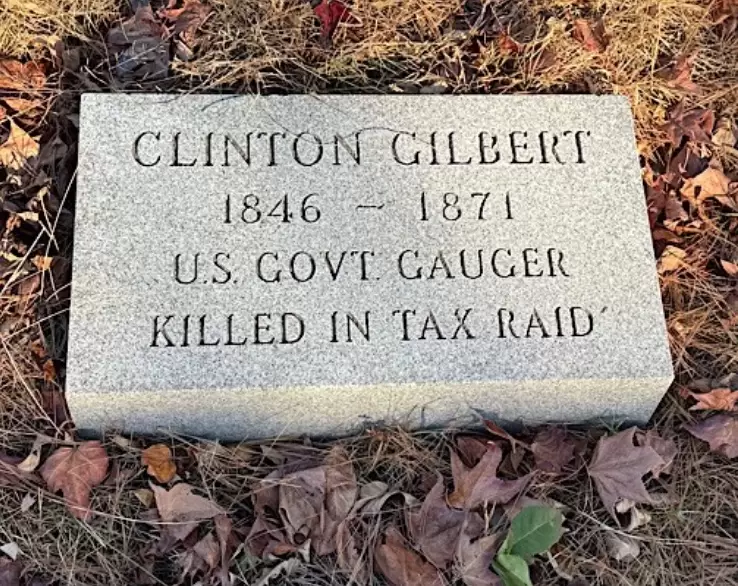

GILBERT, CLINTON (1846-1871). Unknown rank, United States Navy. Gilbert was born in Brooklyn. At the time of the 1860 census, he was a 14-year-old living there with his parents. During the Civil War, he enlisted in the United States Navy at New York City on August 27, 1864. His enlistment record (which incorrectly indicates that he was born in Ireland) states that he was 5′ 6¾” tall with hazel eyes, light hair and a light complexion. As per an article about his death in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on July 18, 1871, he served under Admiral David G. Farragut on the USS Hartford in the Gulf Squadron and participated in the campaigns at Mobile Bay, Alabama, and New Orleans, Louisiana. He was discharged at New York City on September 1, 1865. After the War, he took a clerkship at a grain house, then entered a banking firm on Wall Street. Two days before his death, he became a gauger for the Office of Internal Revenue of the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

As per a memorial biography, Gilbert was shot while he was part of a team of about 40 deputy revenue collectors and deputy United States marshals raiding several stills near the Brooklyn Navy Yard on July 14, 1871. These distilleries manufactured spirits in violation of the revenue laws. The raiding force assembled at the U.S. Marshal’s Office on Montague Street in Brooklyn at 2 a.m., heavily armed with revolvers and clubs; the Marine Corps provided assistance at the Navy Yard. The Treasury officers were fired upon by about 20 “toughs” who were hiding on Hudson Avenue. Gilbert was shot in the lower back and the bullet passed through his abdomen. He died two days later at the Marine Hospital in Brooklyn. Two other agents were injured in the raid. Though the bricks of the distillery were still warm when the raiders got inside, the still was gone.

On July 20, 1871, an article about Gilbert’s funeral, which took place at the Washington Avenue Baptist Church, appeared in The New York Times. That article reported that the offices of the Revenue Department closed at noon and that 60 employees were present at the church along with a detachment of the 14th Regiment who served as a guard of honor, and a large delegation from the War Veterans’ Union Club, of which Gilbert was a member. Gilbert was lauded as one who fell “in the path of duty” and the band played the Dead March from “Saul” as his coffin was carried to the flag-draped hearse. General James Jourdan (see), the United States Assessor and Gilbert’s superior, was one of the pallbearers.

The Internal Revenue Record and Customs Journal, in it issue of July 22, 1871, noted Gilbert’s death and stated: “These attacks upon the bold violators of the revenue laws, located in Irishtown, as it is called, endangers the lives and limbs of those who participate in them, as is proven by the fact that one of the attacking party in this instance, Mr. Clinton Gilbert, a United States gauger, was killed while in the faithful exchange of his duty as an officer of the government.” That publication, which confirms Gilbert’s Civil War service, concluded, in a letter to Assessor Jourdan, a plea to Congress: “In may not be improper to inform your whole force that in view of the growing perils of the civil service, it is my intention to recommend to Congress, through the proper channels, that pensions shall hereafter be granted to those disabled, and to the families of those slain in the internal revenue service, who merit the same consideration as the sailor and soldier maimed or killed on the battlefield.” An article about the inquest related to Gilbert’s death appeared in The New York Times on July 22, 1871. General James Jourdan testified as did several other agents who were at the scene. The inquest jurors determined that Gilbert died in the line of duty and recommended that the civil authorities in Brooklyn offer a reward for the apprehension and conviction of the person responsible for wounding Gilbert. He was a member of Wadsworth Post #4 of the G.A.R. and the War Veterans’ Union of New York City. His office, which after his death was draped in the colors of mourning, issued resolutions attesting to his fine character, integrity, and intelligence. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported later that month that the Treasury Department of the Office of Internal Revenue in Washington, D.C., posted the following message promising a large reward of $5,000 for information leading to the arrest of Gilbert’s assassin. His death was considered “a painful memory with his friends and a sorrow to all law-abiding citizens.” The notice read:

By and with the advice and consent of the Secretary of the Treasury, I do hereby offer, for information that shall lead to the arrest and conviction of the person or persons who, on the 14th inst., at the City of Brooklyn, in the State of New York, mortally wounded Clinton Gilbert, officer of Internal Revenue, then engaged in the discharge of his duty-five thousand dollars. A Pleasonton, Comptroller, Internal Revenue. July 26, 1871

Section 93, lot 2531.

GILBERT, FREDERICK (1836-1897). Private, 71st Regiment, New York State Militia, Company G. Born in New York, Gilbert enlisted in 1861, and served for three months with the 71st Regiment. At the time of the 1863 Draft Registration and the 1870 census, he was working as a policeman. The 1880 census indicates that he was a government contractor, and, according to the 1892 New York State census, he was a bank officer. In 1892, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 859,801. He last lived at 392 10th Street in Brooklyn. Alice Gilbert, who is interred with him, applied for and was awarded a widow’s pension in 1897, certificate 461,483. Section 115, lot 20934, grave 5.

GILBRAITH, JAMES H. (1845-1934). Private, 37th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company G; United States Navy. A machinist by trade, Gilbraith enlisted for 30 days on June 18, 1863, at New York City, and mustered out of the 37th New York on July 22. He then enlisted in the Navy at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in December 1863 and served for one year on the warship State of Georgia until his discharge at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in November 1864. He re-enlisted for another year, served as a coal passer, and was made chief engineer. His pension index card indicates that he also served on the USS Princeton and the USS Vermont.

According to the 1888 New York City Directory, he was a conductor; the 1900 census lists him as a dispatcher. The 1915 and 1925 New York State censuses report that he was a railroad dispatcher. Gilbraith received a pension from the Navy, certificate 41,178. His family later used the spelling “Galbraith.” Section 7, lot 9326, grave M.

GILBY, JOHN R. (1838-1896). Private, 5th New York Heavy Artillery, Company K. A native of Queens, New York, Gilby enlisted at New York City on March 23, 1864, and mustered into the 5th New York on that date. As per his muster roll, he was a boat builder who was 5′ 9″ tall with blue eyes, light hair and a fair complexion. He mustered out at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, on July 19, 1865. The 1880 census states that he was employed as a ship carpenter.

Articles in the Brooklyn Standard Union on May 20 and June 9, 1885, report that Gilby was brought before a judge and charged with insanity. Apparently, this was not the first time that he behaved in an unsound manner although Gilby testified that he worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for 20 years and had never been arrested. He was charged with assaulting his married daughter who lived with him. Gilby’s wife testified that her husband had been acting strangely and talking incoherently for two years but had taken a turn for the worse and was violent. The Charities Commission was set to determine his sanity.

A subsequent article in the New York Tribune on May 21, 1886, reports that Gilby was declared insane and committed to an asylum after taking his wife for a carriage ride during which he lashed at the horse with such fury that it ran away three times causing Mrs. Gilby to suffer from fright. However, he appears to have recovered; he was a member of the Stephen Thatford Post #3 of the G.A.R. and was elected its chaplain for 1892. In 1892, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 838,635. Gilby last lived at 15 Webster Place in Brooklyn. He succumbed to heart disease. Josephine Gilby, who is interred with him, applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1896, certificate 437,906. Section 135, lot 14964, grave 588.

GILCHRIST, GEORGE D. (1841-1885). Private, 2nd Florida Cavalry, Company K, Confederate States of America. A New Yorker by birth, he enlisted at Callahan in East Florida on May 16, 1862, and mustered immediately into the 2nd Florida Cavalry. As per his muster roll on that date, his horse was valued at $150 and the equipment at $15; his muster roll for March-April 1863 showed that the horse was valued at $350. In 1870, he was living in Jacksonville, Florida; that is also where he last lived. His death was caused by a hemorrhage. Section 35, lot 3049.

GILCHRIST, JOHN (1840-1883). Private, 13th Regiment, New York State National Guard, Company A. Originally from Canada, Gilchrist enlisted at Brooklyn on May 28, 1862, as a private. He mustered immediately into the 13th Regiment and mustered out at Brooklyn after three months on September 12. According to the 1880 Brooklyn Directory, he was a carpenter. His last residence was 701 Third Avenue in Brooklyn. He died of phthisis. In 1891, Emma Gilchrist’s application for a widow’s pension was granted, certificate 357,825. Section 15, lot 17263, grave 833.

GILCHRIST, JR., ROBERT (1825-1888). Captain, 2nd New Jersey Infantry, Company F. A Jersey City, New Jersey, native, his father, Robert Gilchrist was clerk of Hudson County from 1840 through 1865 and mayor of Jersey City from 1850-1852. Robert jr. was educated in the private schools, studied law, and was admitted to the New Jersey Bar in 1847; his first work was as an assistant in his father’s office. The 1850 census reports that he lived in Jersey City with his parents and siblings and was a lawyer. In 1859, Gilchrist served in the New Jersey General Assembly.

As per his soldier record, Gilchrist enlisted as a captain early in the Civil War, on May 20, 1861, and was immediately commissioned into Company F of the 2nd New Jersey Infantry. He mustered out on July 31, 1861, at Trenton, New Jersey. Another biography and his obituary note that he served throughout the Civil War—that is apparently incorrect.

Remaining active in politics, he made an unsuccessful bid as a Democrat for the House of Representatives in 1866. As per his biography in Appletons’ Cyclopedia of American Biography, which reports his Civil War service throughout the conflict, he had been a Republican but became a Democrat during Reconstruction. Gilchrist was the attorney general of Jersey City from 1870 through 1875; during that time, he was appointed to a commission to revise the New Jersey State Constitution. Appletons’ Cyclopedia of American Biography notes that his specialty was constitutional law and his interpretation of the 15th Amendment secured suffrage for African-American men in New Jersey. Gilchrist was also instrumental in maintaining funds for public education in his home state. The 1880 census reports that Gilchrist was married with children, lived at 289 Barron Street in Jersey City, and worked as a lawyer.

His obituary in The New York Times notes his gifts as a lawyer, his commanding presence and his powerful voice. That obituary indicates that he was the special counsel for the Matthiessen & Weichers Sugar Company and the Lehigh Valley Railroad, among other corporations, and that he commanded the largest legal income in New Jersey. One of his most famous cases was that of uncovering a conspiracy of forgers, including a fake widow, which attempted to defraud an elderly miser, Joseph L. Lewis, of his millions; Gilchrist was paid $150,000 for his services and more than $600,000 was paid to the National Treasury to reduce the national debt. He last lived at 65 Mercer Street in Jersey City. His death was attributed to heart failure. After his death on July 6, 1888, he was interred at the Bergen Church Vaults; his body was removed and he was interred at Green-Wood on December 31, 1888. His biography in Appletons’ Cyclopedia of American Biography reported that his large law library, with his annotated books, was sold at auction six months after his death. His wife, Fredericka Raymond Beardsley, wrote The True Story of Hamlet and Ophelia (1889). Section 120, lot 17805.

GILDERSLEEVE, BENJAMIN F. (1835-1878). Acting third assistant engineer, United States Navy. A native of New York, he was a clerk as per the census of 1860. Gildersleeve began service in the Navy as an acting third assistant engineer on December 28, 1861, and resigned on June 24, 1862. The 1872 New York City Directory reports that he worked as a clerk. His last residence was 9 West Houston Street in Manhattan. He died of Bright’s disease. Section 168, lot 16378.

GILDERSLEEVE, WILLIAM (1843-1926). Private, 13th New York Heavy Artillery, Company I. A New York native, Gildersleeve’s Draft Registration of July 1, 1863, noted that he was single and lived in Northport, New York. He enlisted as a private at Jamaica, New York, on September 27, 1864, and mustered that day into the 13th New York Heavy Artillery. As per his muster roll, he was a cab driver who was 5′ 7¾” tall with brown eyes, light hair and a light complexion. He mustered out with his company on June 28, 1865, at Norfolk, Virginia.

The 1870 and 1880 censuses report that Gildersleeve was living with his parents in New York City. In 1896, his application for an invalid pension was approved, certificate 1,100,559. The New York State census for 1925 notes that he was living in Brooklyn with his daughter and her husband. He last lived at 665 East 21st Street in Brooklyn. His death was attributed to prostatic hypertrophy. Section 181, lot 11046.

GILFILLAN, JOHN MATHEWS (1835-1890). Captain, 43rd New York Infantry, Companies G and C; 39th New York Infantry, Company I; corporal, 52nd New York Infantry, Company F. Gilfillan was born in New York City in 1835; his soldier record incorrectly indicates that he was 24 when he entered service, suggesting a birth year of 1837. In 1860, he worked as a clerk for the New York City Charity and Small Pox Hospital and Fever Tents. During the Civil War, he enlisted as a first lieutenant at Schenectady, New York, August 29, 1861, and was commissioned into Company G of the 43rd New York on September 16. He was promoted to captain on January 25, 1862, and was transferred to Company C on July 18, 1862. He served with his brother William (see) in the 43rd and is mentioned several times in William’s letters to his mother, Mary Mathews Gilfillan, many of which are in the possession of Daniel Armstrong, direct descendant of Sam Gilfillan, William and John’s brother.

The 43rd New York first arrived at Washington, D.C., then headed to Alexandria, Virginia, where they joined the Army of the Potomac. Among the engagements of the 43rd New York were these in Virginia: Siege of Yorktown and the Battles of Lee’s Mills, Williamsburg, Garnett’s and Golding’s Farm, Savage Station, White Oak Swamp, and Malvern Hill. As of August 15, 1862, the regiment, now consolidated into five companies, fought in Maryland at the Battles of Compton’s Creek, Sugar Loaf Mountain, Crampton Pass and Antietam. As per his brother’s letter home, he submitted his resignation on September 5, ostensibly hoping for a promotion in a new regiment. That resignation was accepted on September 19, 1862.

He was listed as a surveyor on the 1863 New York Draft Registration. As per the research of Daniel Armstrong, Gilfillan re-enlisted as a private on August 24, 1863, and mustered into Company F of the 52nd New York, perhaps awaiting a new commission. He was promoted to corporal on November 1, 1863. The regiment fought in Virginia during that five month period at the Battles of Auburn, Bristoe Station, Mitchell’s Ford, Robertson’s Tavern and the Mine Run Campaign. Although his service is noted on regimental rosters, it is not part of his pension files.

After his brief service with the 52nd Regiment, Gilfillan re-enlisted as a captain at the 14th Congressional District, New York, on January 18, 1864, and was commissioned into Company I of the 39th New York on February 12. On May 12, 1864, while serving in command of Company K of the 39th New York, he was wounded through the left shoulder at the battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia, while leading a charge on the enemy. As a result of his injury, he was hospitalized and then was discharged for disability on September 12, 1864. Re-commissioned as captain of Company I on October 11 of that year, he fought at the Battle of Hatcher’s Run, Virginia, on December 8, 1864, at which time his wound reopened. After an arrest for an unknown reason on December 23, 1864, he was released two days later, and on December 30 was granted a leave of absence for 30 days. The request noted, “This officer has behaved with great gallantry during the campaign and exposed to the storms at Hatcher’s Run for 36 hours on picket duty.”

On March 7, 1865, he tendered his resignation with an accompanying surgeon’s note attesting that his shoulder injury made him unfit for duty. A day before his discharge, Gilfillan was charged with “conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman” for his actions on March 14, 1865, including using abusive language against an officer, being intoxicated, wounding an officer while in a drunken frolic and denying that action, attempting to incite officers and enlisted men to mutiny, and refusing arrest. Despite his record of numerous arrests, Gilfillan was honorably discharged on March 15, 1865, at Petersburg, Virginia.

Apparently a rather unruly soldier and a more colorful character than his brother William, John Gilfillan’s military file contains stories of pub fights, courts-martial, and the like, predating the incidents enumerated above. In one of his brother William’s letters, dated June 19, 1862, he says, “John is getting along finely and I think is changing for the better in his conversation he doesn’t curse so much as he used to.” How much he changed for the better is uncertain, however, because his file indicates that in February 1864, “Captain Gilfillan was put under arrest for drunkenness and absence from dress, parade, and confined to the limits of regimental camp.” The next month, on March 22, he and a second lieutenant were both found intoxicated, after celebrating Gilfillan’s apparent transfer to the Navy. After insulting and using disrespectful language against a lieutenant, the two men were arrested and charged with drunkenness and conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman; the two were ordered to report to the adjutant of the Guard. The examining board did not appoint Gilfillan for a transfer to the Navy and he was released from arrest on March 25. In addition, he was arrested for unspecified infractions in April 1864, released and restored to duty on May 6.

He applied for and received an invalid pension on May 15, 1865, certificate 50,407. In 1867, Gilfillan married Sarah Shipp in Corona, Queens; at that time, he worked as a clerk for the New York City Alms House at Blackwell’s Island. In 1874, he was employed by the New York City Fire Department as a painter and tower watchman. At the time of the 1880 census, he was living in Newtown, Queens, with his wife and son and working as a painter. He last resided in Corona, Queens, where he was a member of the 17th Separate Company, a National Guard Company that drilled at a nearby armory. His wife, Sarah Gilfillan, applied for and received a widow’s pension in 1890, certificate number 299,908. Section 162, lot 14181.

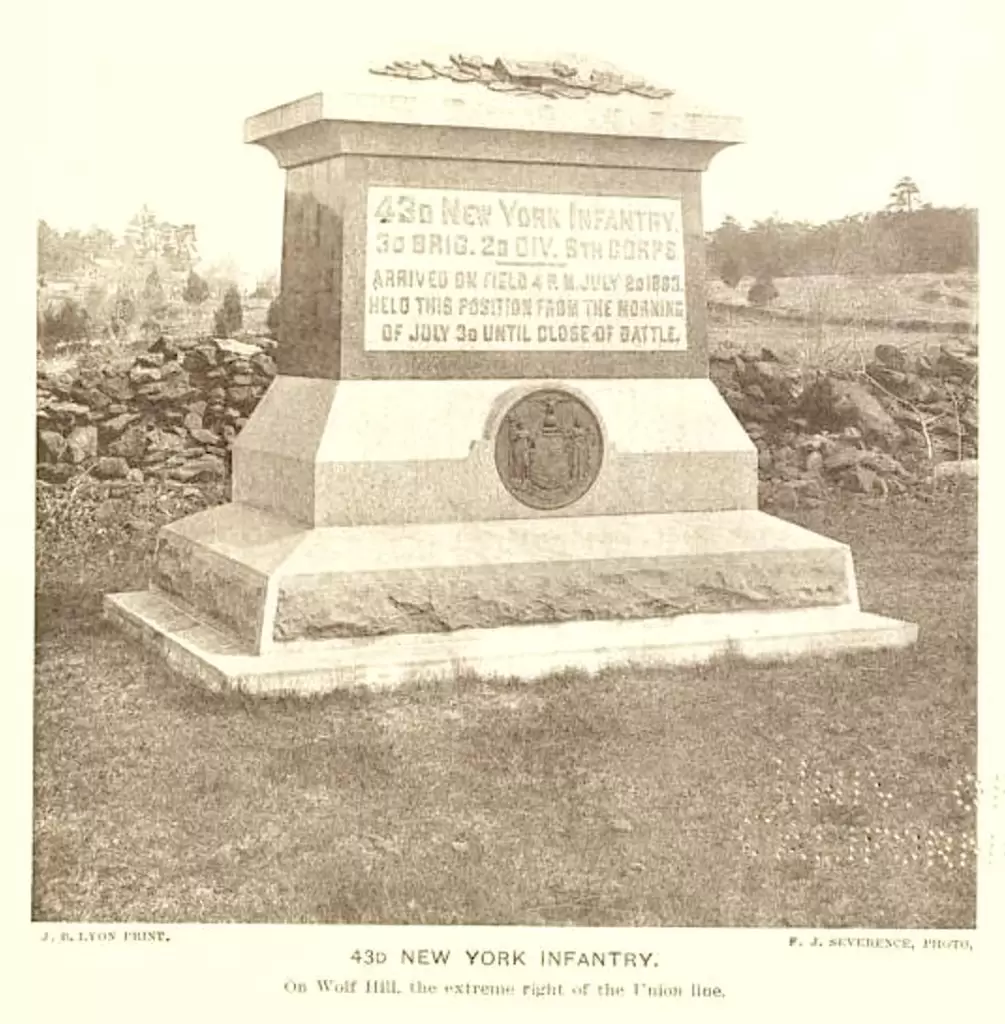

GILFILLAN, WILLIAM H. (1842-1863). Captain, 43rd New York Infantry, Companies G, C, and A. Gilfillan, a native New Yorker and resident of 134 East Broadway in Manhattan, came from a large family of seven children. In September,1853, his father abandoned the family, leaving his mother dependent on financial support from her children. He enlisted as a private on August 14, 1861, at New York City, mustered into Company G of the 43rd New York on September 16, and became a second lieutenant on January 24, 1862. Francis L. Vinton, the colonel and commanding officer of the 43rd Regiment, praised Gilfillan’s conduct in describing the action at Garnett’s Farm, Virginia, on July 10, 1862, when the soldiers, on picket, were under heavy fire at sunset for 45 minutes and 42 men were killed or wounded during the barrage. On July 18, 1862, he was transferred into Company C, was promoted to first lieutenant on September 19, 1862, and then to captain on June 2, 1863, effective upon his transfer to Company A. He was killed in battle at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 3, 1863, on the slope of Wolf’s Hill, the very end of the Union line, while leading Company A in flushing out snipers from the 2nd Virginia who were positioned in the woods there.

Many of Gilfillan’s Civil War letters survive, copies of which have been provided by Dan Armstrong, a direct descendant of Sam, William’s brother, and they provide a rare first-hand account of life on and off the battlefield. The letters show a man whose family was never far from his thoughts, even as he confronted the reality of war. He frequently speaks of his love for his family and his special affection for his mother and worries about her well-being. He often asks for news from and about them and tells of his happiness at receiving letters from home. Almost all of William Gilfillan’s correspondence is addressed to his mother Mary, who lived on East Broadway in New York City, and many conclude with “from your ever loving son.” Only two in the collection of letters are to others: one to his brother Sam, the other to his sister. The excerpts and letters below are in the original words.

Gilfillan’s letters from 1861 describe his thoughts early in the War. Writing from home to his brother Sam on July 26, 1861, he confides that he has to “keep the papers from her [our mother] that have any news” about the fighting, but reports that “Joseph Perly and Jack where [sic] both in the action at Bulls Run but both came out safe.” He adds that “Jack will go out as 1 Lieut of a volunteer Co. under Capt. Bill Mathews who you know is a military man having served under Walker in Nicaragua.” In a letter dated September 13, 1861, Gilfillan writes to his mother from Washington about his mustering: “we started from New York Friday night at 12 oc’lk and did not get into Phil. until 12 o’clock Saturday when we got dinner and then started for Washington passing through Baltimore….We expect to be here about a week before we cross the Potomac.” In this letter, as in many others, he adds that “John [see] is well.”

In the following letter to his mother from Camp Graham in October 1861, he lets his mother know about his life as a soldier:

Dear Mother,

I am well and hope this finds you the same. I am getting along finely as a soldier. My health was never better. We have had 3 days wet weather but my tent is as dry as my old room and I have 2 blankets and plenty of straw to sleep on. I have got acquainted with the surgeon of our regiment doing a little writing for him. He has taken a great fancy to me. I caught cold when we were crossing over the Chain Bridge as we had to stand in the wet about 4 hours and I took some syrup he gave me which cured it__. You can tell Sarah that I have plenty of clothing and that we are to get a new suit in two weeks. But I must close as this paper is a little damp I am afraid you won’t understand what I have wrote. Give my love to Aunt Sally and all kind friends not forgetting yourself. Tell Miss Blakely that I wish I had some of her books here as books are a luxury here. Tell Lizzie she must write to me.

From your loving son,

William

PS I am getting so selfish that I forgot to mention John in either of my letters. He is well and is getting along finely.

Making sure his mother has enough money to live on is a constant concern that he reveals in several of his letters. Writing from Washington on November 7, 1861, he says that he has deposited $15 for her at the Adams Express Company and that “I would like to have send [sic] more but I only receive $17 per month and Government would not pay me for more than 1 month and 3 days which was about $18.” He continues, “Capt. Mathews arrived here with 20 Recruits on Monday.” On November 22, he admonishes his mother not to save for him the money he sent her: “You have always supported me and now that I am of an age able to work and able to send a little money to you I want you to use it.” He boasts of “the cosy [sic] little tent I have with a stove built in the ground” and the bed and mattress that he has constructed.”

It would be several months before he left his camp near Washington, Camp Griffin. “We are still encamped at the same place [Camp Griffin] and I think we will be here for some time,” he writes on December 8, 1861. This letter is also noteworthy for containing a sketch of his uniform stripes. On December 16, Gilfillan tells his mother that the regiment has “been pretty busy building log houses for the winter,” and reports some trouble with the regiment’s sutler who “has been in the habit of charging double prices for everything he sold.”

In a letter dated mid-March 1862, from Flint Hill, near Fairfax Court House, Virginia, he writes his mother that his regiment has finally left Camp Griffin “to meet the enemy but they had left Manassas and retreated. 2 Regs of Cavalry now occupy the Battle ground (Bull Run). We expect to move tomorrow morning.” He also mentions that he has “just been officially notified of my appointment as 2nd Lieut.”

Writing from a camp near Alexandria, Virginia, on March 16, 1862, he remarks to his mother about the “Pretty sight” of the soldiers marching by:

Dear Mother,

I have at last a chance to write to you. We left Camp Griffin last Monday morning and have been strolling through Virginia ever since. The first night we camped near a place called Flint Hill about 1 and a half miles from Fairfax Courthouse. We then shifted about 4 miles the other side of Fairfax and yesterday morning we passed back through Fairfax to here on our way. As we suppose to take transports to go and join Burnside. Our camp is right on the side of a road and it is really a pretty sight to see the soldiers pass by us there must have been 6,000 of them, some going to the same place as we are and some going to take the places we had left in the Army of the Potomac. There is several New York reg[imen]ts going with us among them the 14th of Brooklyn who we cheered as they passed by. Answer this is All perhaps I may wish from you is a pair of military boots and a sash but don’t buy them until I write to you again. John is well and in good spirits.

I must close as mail is waiting.

From your ever loving son,

William PS We have not got paid yet. I have just heard from John that we are to lay here 3 or 4 days and if you answer this as soon as you receive it I may get it. The reason we wait is there is not enough coal for transports.

Gilfillan expresses confidence about impending action in a letter from Camp No. 21 in the field, June 19, 1862: “We have not made any move yet against the enemy but I think we will in a few days. The Enemys [sic] are in greater force than we are and may defeat us though we have all confidence in Gen. McClellan.” In a revealing comment about his brother, he also reports that “John is getting along finely and I think is changing for the better in his conversation he doesn’t curse so much as he used to.”

Writing from a camp near Harrison Landing, Virginia on July 14, 1862, he expresses his concern for his mother’s well-being, makes requests for some personal wants and notes changes in the regiment:

Dear Mother:

The paymaster paid us today for 2 months. I send by Express $150.00 for you. You can use it for what you want it. Uncle Sam still owes me 2 months pay which we expect to be paid in the course of a week and then I will be able to send you $50 more and 100 to put in the bank. Now mother you must stop slaving and more. I have got a chance to do something for you Mother and you must have a servant. I received a letter from Sarah this morning the first one in some time and I was very glad to hear from home and sorry to her that you still fretted about us and that Lizzie’s cough was still bad. I wished I was in a position to render you independent for life. I will try at any rate.

John is well and so am I. He would send you something too but has got to get a new uniform and other things now but will send something the next payday. Enclosed you will find $10 which I wish you would get me a pair of military shoes high uppers size 7 and 2 fine summer Cambric shirts (color red) and also a box of Pomatum [hair grease]. John also want some shirts the same as mine about 3 for him and he will send the amount you pay for them. 11 Officers have resigned but I do not know whether there (sic) resignations will be accepted. They have different ideas about it. Some resign on account of Cannon Fever, some sick of this service, and some to get positions in the new new regt now forming in New York. If they are accepted, it will leave John Senior Captain with the first chance for Major. I perhaps will get the position of Adjutant or Quartermaster. Write on receipt of this and let me know how you are getting along and whether you have let the house (upper part). Inform Aunt Sally that I shall write a letter to her in a day or two and thank her for those papers she sent me. I don’t think we will leave here for a month or two. We are camped right on the bank of the James River. I send the money by Adams Express to you at 134 East Broadway. Remember me to Sam, Lizzie, Aunt Sally and Stewart and all the folks. Hoping to hear from you soon.

I am your baby boy,

Billy

In a letter dated August 1862, from the same camp near Harrison Landing, he mixes small talk about home with war-related news. Captain Mathews, mentioned a few times in earlier letters, appears again here: “I heard that Capt. Mathews is getting up another company in Schenectady. I think he had better stay out of the Service before he becomes disgraced.” In the same letter, Gilfillan expresses the opinion that “I don’t suppose that we will move from here in some time not until the new men called for come here anyhow which will take at least 3 or 4 months.” And he informs his mother that “some of our men who where [sic] taken prisoners have joined us again haveing [sic] been exchanged” and that “our company has been consolidated with Company C.”

Apparently, Gilfillan’s prediction about his stay at Harrison Landing proved incorrect, for he writes again from a camp near Alexandria, Virginia, on September 5, 1862. In this important letter, he tells his mother about the Battle of Second Bull Run:

our Regiment lay near Alexandria, Va. about 2 days when we where [sic] ordered up the road to a place nearer Fairfax Court House where we remained a day and a half while the fighting was going on at Manassas….we where [sic] ordered to the Battle but did not get there before 7 oclk when the fighting was decided and we could do nothing but [illegible] the rear we understood at the time that Stonewall Jackson was surrounded but that McDowell gave way on the left and then the Rebels came in on our Side however the Soldiers have got a Bad Idea of McDowell.

William Gilfillan expresses his opinion about what John, who had recently tendered his resignation, should do, in a letter from a camp near Sharpsburg, Maryland, written September 7, 1862: “John I suppose has got home by this time. I think if he would apply he could get the majorship of this Regiment. I wish he would try and get it.” And once again he looks to the future: “The General of our Brigade thinks that if we move from here we will go to Hagerstown about 10 miles from here where we will winter for the rest of the cold days.” Additional news about the war comes in a letter from a camp near Harpers Ferry, Virginia, on September 16, 1862:

We have not been engaged with the Enemy yet though the Division next to us had a brush yesterday morning and the night before and took about 1000 prisoners. We are [illegible] in a beautiful Valley in the Blue Ridge Mountains (a Place called Pleasant Vale) about 6 miles from Harpers Ferry which we have just heard has surrendered to Stonewall Jackson. Gen. Burnside though who is on our Right has counteracted this and has taken 15000 prisoners. I do not suppose we will be engaged. We are acting as the Reserve Corps and don’t get a shot at the Rebs.

However, two days later, on September 18th, he writes from the battlefield:

our Regiment supported a Battery all day yesterday but we had no body hurt though the enemy hurled grape and canister at us but we lay down and it whent [sic] over us. We beat the Rebels badly killing Gen. Early and several other Rebel Generals the field in front of us is covered with their dead and wounded.

In the last letter in the collection from William, he writes his sister from Fairfax Court House, Virginia, on June 19, 1863. The subsequent letters are from comrades. “We left Fredericksburg Saturday Eve 13 inst and commenced the pursuit of Gen. Lee who we understand has marched into Pennsylvania we have had some severe marching 2 nights and a day without rest as we had to keep up to the wagons. We feel satisfied that Gen. Lee will have some trouble in getting out of Maryland and Pennsylvania.” The next letter, dated July 28, 1863, from a camp near Warrenton, Virginia, was written by a comrade and describes Gilfillan’s death at the Battle of Gettysburg:

I would like to have you know all his movements and will begin at the 1st of July the date of his last letter. On that day we went on picket between Manchester and Westminster about noon – at nine oclock p.m. we moved back and marched from there until about five p.m. July 2 when we reached the battle field of Gettysburg a distance of thirty seven miles. We were all very tired but as the battle was raging we did not get any rest ‘til darkness put a stop to the fighting….I had only lain a few moments when we got the order to fall in…we moved off to the right of our army to drive back the enemy’s skirmishers and establish a picket line. As soon as we approached the place where the enemy were supposed to be the right (Co. A. Billy’s) and left companies were ordered forward…they had only started when the firing commenced and the balls went over our heads as we advanced…. (the left company) had to advance through an open field and though the balls flew thickly past them none were hit. William’s Co. moved forward through a woods the enemy was nearer than they expected and in strong force concealed behind rocks and trees. To enable you to form an idea of how the Regt. was posted I will make this [here the letter writer sketches the battlefield]. You will see that my Co. is some distance from Co. A….William and one man in his company were killed almost immediately….William was struck below the Stomach the ball passing out of his back. He did not suffer much pain I’m sure from his appearance.

His mother applied for a pension in September, 1863, number 32,032. The men of the 43rd felt close to their captain and, when they visited the boulder where Gilfillan was propped against as he lay dying, the veterans placed shards of granite as a memorial to their fallen leader. His name appears on a monument to soldiers and officers from New York who fell at the Battle of Gettysburg. Section 162, lot 14181.

GILFILLAN, WILLIAM J. (1839-1906). Acting assistant surgeon, United States Navy. According to his written answers to Navy Examination Board questions, dated March 27, 1863, he was born in Londonderry, Ireland, and studied “Mathematics, English Grammer, Geography, and a little philosophy . . . and studied Latin and some Greek.” He reported that he had graduated from Queen’s College there, immigrated to Brooklyn in 1855, studied medicine under Dr. Alexander Cochran, then entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia, graduating in 1860. He also wrote to the Examining Board that “I have had one year’s experience, as resident Surgeon in the Brooklyn City Hospital.” In response to a question on the exam about the classification of wounds, he wrote: “Wounds are divided into Incised, Lacerated, Punctured & Poisoned some add Gun shot wounds.”

After he successfully completed his written Naval examination, he served as an acting assistant surgeon in the Navy, aboard the USS Nipsic, from April 17, 1863, through December 27, 1864. After the war, he worked as a doctor at Brooklyn City Hospital, entered Columbia Law School in 1867, and graduated in 1869, but did not practice law. At the time of his death, which was caused by nephritis, he lived at 1905 86th Street in Brooklyn. Section 21, lot 10487.

GILL, ROBERT (1826-1906). Second lieutenant, 6th New York Infantry, Companies C and K. A New Yorker by birth, he served in the Mexican War. The census of 1860 states that he was a machinist. At the start of the Civil War, he enlisted as a sergeant at New York City on April 25, 1861, and mustered into Company C of the 6th New York five days later. He was transferred to Company K, rose through the ranks becoming a sergeant major on May 25, 1861, and transferred into the Field and Staff that day. On August 15, he transferred back into Company C and was promoted to second lieutenant. His commanding officer, Colonel William Wilson, recognized him and two others in his field report from Camp Brown, Florida, on October 14, 1861, noting “…the valuable assistance they rendered me in keeping my men in order, and their good behavior while under fire of the enemy.” Gill applied for and was granted an invalid pension in 1894, certificate 931,204. As per the census of 1900, he was working as a machinist. He last resided at 117 Longwood Avenue in the Bronx. His death was attributed to “old age.” Section 61, lot 3665.

GILLESPIE, BENJAMIN P. (1844-1902). Private, 149th New York Infantry, Company C; 102nd New York Infantry, Company E. Gillespie was born in New York City. After enlisting as a private at Fishkill, New York, on February 8, 1865, he immediately mustered into the 149th New York. As per his muster roll, he was a clerk who was 5′ 6″ tall with hazel eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion. Gillespie transferred into the 102nd New York on June 10, 1865. He mustered out on July 21, 1865, at Alexandria, Virginia. The 1877 New York City Directory and the censuses of 1880 and 1900 indicate that he was in the hardware business. His last address was 2322 Eighth Avenue in Manhattan. Gillespie died of pneumonia. Section 192, lot 27557, grave 3.

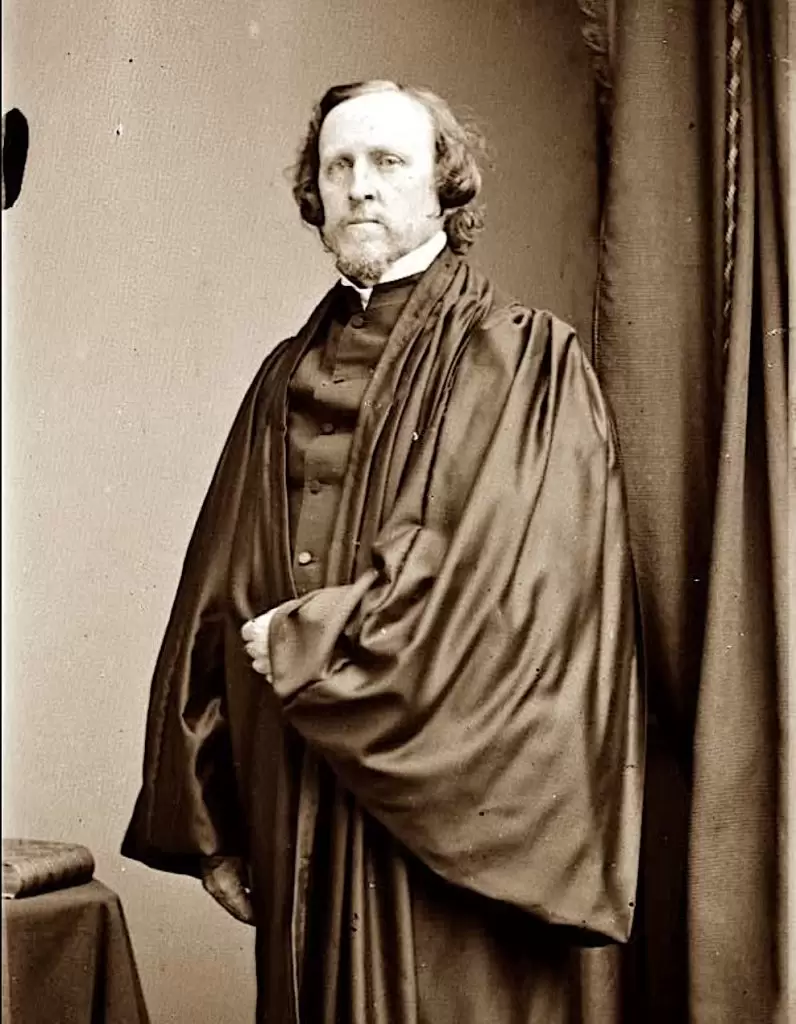

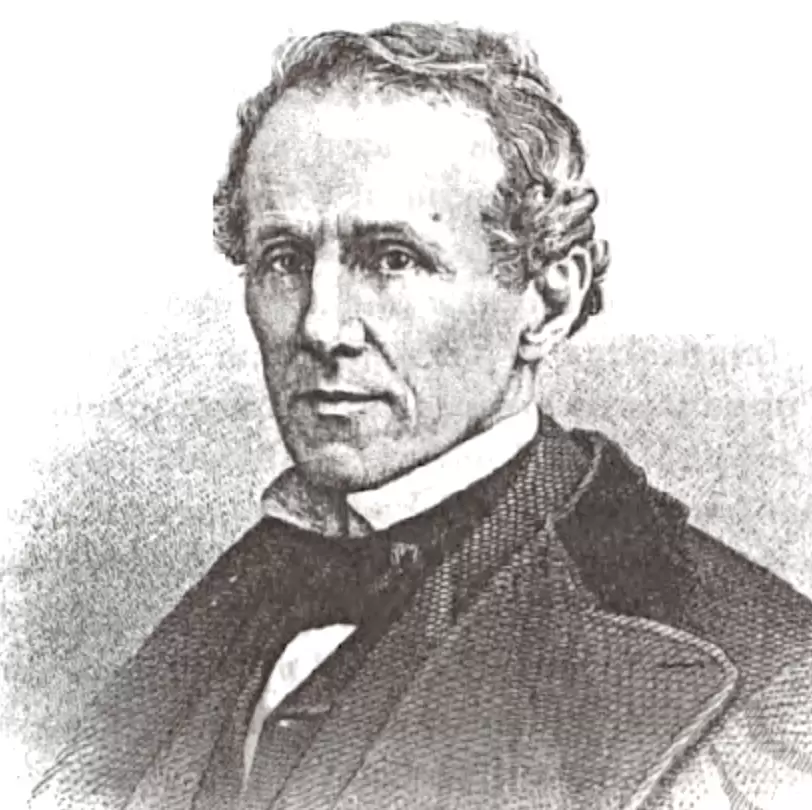

GILLETTE (or GILLET, GILLETT), AVRAM DUNN (1807-1882). Reverend and consoler to Lewis Powell, co-conspirator of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of John Wilkes Booth. The Reverend Dr. Avram Dunn Gillette, who was born in Washington County, New York, was drawn to religion as a teenager and baptized in May 1827. He pursued his higher education at Madison College in Hamilton, New York. From 1831 to 1835, he was pastor of the First Baptist Church in Schenectady, New York, increasing the worshipers from 60 to 600. He then led Baptist congregations in Philadelphia until 1858 where he edited notes about Baptist history in Philadelphia from 1707 through 1807. He relocated to New York City until 1864.

During the Civil War, his sons, Walter (see) William (see), fought for the Union. Reverend Gillette moved to Washington, D.C., in January 1964. On April 25, 1865, his sermon in Washington, D.C., noted the feelings of all people around the world about President Abraham Lincoln’s death. He began:

When the Executive head of a great nation falls, all nations become mourners; for they know that the ruler they look to, to carry them on in improvements and give them desirable perpetuity and stability upon the earth, is also a man, and must ere long die, and may be called to his dread account in a moment least expected, and when they seemed most to need his guiding hand in the affairs which so vitally concern their common and individual good.

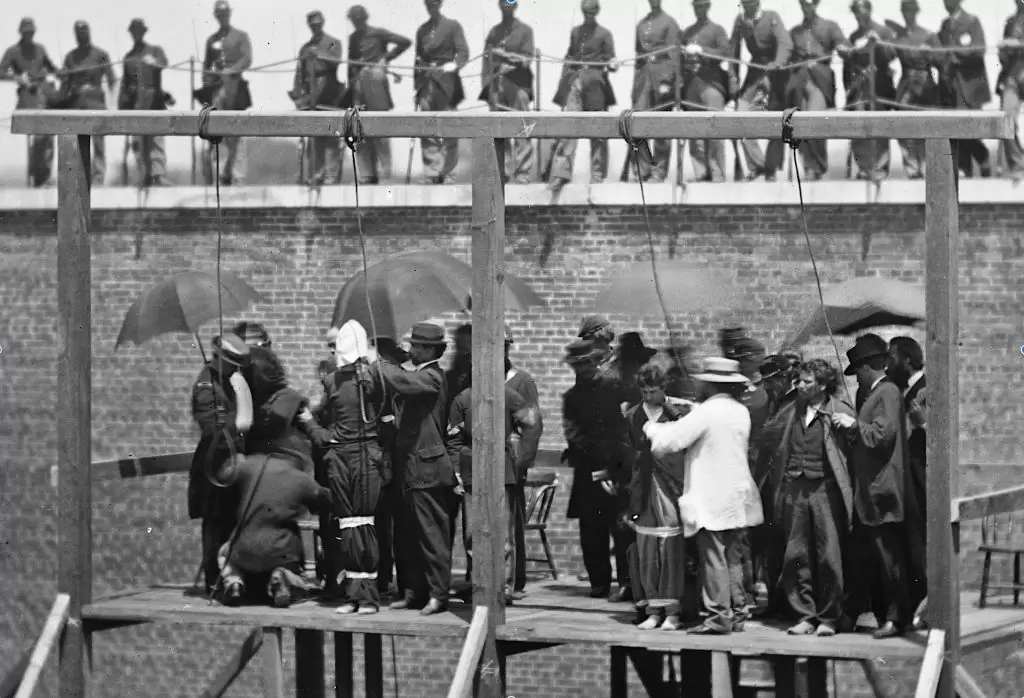

Gillette, however, is best known for his spiritual connection to Lewis Powell, one of the co-conspirators of John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln. Powell’s lawyer, William E. Doster, testified that his client, “at the time had no will of his own, but had surrendered his will completely to Booth.” Powell was found guilty of conspiracy and attempted murder for the knife attack on Secretary of State William Seward and sentenced to hang. Powell first met Gillette, the local Baptist minister, after receiving his sentence and the night before his execution by hanging. The two prayed together and Powell supposedly told Gillette that he had worked with the Confederate secret service in the months before the assassination. Powell reportedly confided to Gillette that his favorite hymn was “The Convert’s Farewell.”

As per “A Knock on Rev. A.D. Gillette’s Front Door” in Alias “Paine” by Betsey Ownsbey, Gillette received a knock on his door on July 6, 1865, by Assistant Secretary of War Thomas T. Eckert with a request for Gillette to visit the arsenal where Powell was being held. The following exchange occurred:

Upon reaching the Arsenal, the perplexed but willing and kindly minister was conducted at once to Powell’s cell. The good clergyman knew nothing of the condemned man and was “much concerned to learn why he had chosen him, a loyalist, in preference to other clergymen of his own faith who were in admitted sympathy with the Southern Cause.”

Powell explained that he had heard him preach not long before:“Do you remember a bitter, sleety Sunday last February, when you preached in the Reverend Dr. Fuller’s church in Baltimore? It was then I heard you. I sat with two ladies in one of the end pews to the right of the pulpit. There were scarcely more than a score of people in the church as the walking was so icy and dangerous. My companions and myself were the only occupants of the end pews on either side of the chancel. I had hoped that perhaps you might remember the circumstances, as you frequently turned towards us as if addressing us.” (According to the “Local Matters” section of the Baltimore Sun for February 13, 1865, this would be Sunday, February 12.)

Powell related to Dr. Gillette that he was the son of a Baptist minister and in conversation pertaining to his mother and family, broke down in tears, weeping bitterly for the first time since his sentence had been pronounced.

In conversation with Powell, Dr. Gillette claimed that the prisoner told him that:“he thought he was doing the right thing in attempting to kill Secretary Seward, as he still claimed to be a Confederate soldier; aside from that, he admitted that he believed it would give peace to the South. He thinks now that it was all wrong, and blames the Rebel leaders for his death, though he did not fear to die. Several times he expressed his thanks for the kind treatment which he received from officers while in the prison. He stated that he was led into the conspiracy by Booth and John Surratt.

Powell continued to agonize over Mrs. Surratt, telling the Reverend Dr. Gillette: “She at least, does not deserve to die with us. If I had no other reason, Doctor – she is a woman, and men do not make war on women.”

Dr. Gillette was impressed with Powell’s intelligence in direct contrast with the newspaper accounts that portrayed him as a coldblooded killer with a moronic mentality. Lewis requested the clergyman to write his parents and tell them he had repented and had his hope of heavenly – if not earthly – pardon. Throughout the long night, the prisoner took special advantage of Dr. Gillette’s ministrations, alternately praying and weeping. His last prayer was, as suggested by his friend, Dr. Gillette, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.” Finally towards dawn, emotionally drained, Powell was able to get about three hours of sleep.

Although Gillette never discussed his conversations with the convicted man, his son wrote that Powell’s death had a profound effect upon his father. Rev. Gillette left Washington, D.C., in 1869, traveled abroad for a year, and settled in Brooklyn in 1870. He later served the Baptist church in Sing Sing, New York, and took sick in 1880. The census of 1880 indicates that Gillette was a “minister of the gospel” in Washington County, New York. He died in Lake George, New York. Section 45, lot 11380.

GILLETTE, WALTER ROBARTS (1841-1908). Surgeon, United States Army. Originally from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he attended medical college, his father was the Rev. Dr. Avram Gillette (see). According to his wife’s obituary in The New York Times, he served as a surgeon during the Civil War. After enlisting in 1861 as a surgeon at Philadelphia, he served the Union Army until his discharge in 1865.

After the War, he worked as vice president of the Mutual Life Insurance Company and was a consulting physician at Bellevue, St. Francis, and the Maternity Hospitals. His last residence was 24 West 40th Street in Manhattan. He died of cancer. He was the brother of William P. Gillette (see). Section 45, lot 11380.

GILLETTE, WILLIAM POST (1846-1902). Rank unknown, United States Volunteers, Commissary Department. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, his father was Rev. Dr. Avram D. Gillette (see). William Gillette was educated in New York City. During the Civil War, he entered the Commissary Department, and later took part in Sherman’s March to the Sea.

In civilian life, Gillette worked for the federal government in Washington, D.C., the Post Office, and then was the manager of the brokerage firm of L. W. Minford & Co. on Wall Street. The 1900 census reports that he was a stock broker. According to his obituaries in The New York Times and the New York Herald, which confirm his Civil War service and note that he was present at many of the great battles of the War, he was a member of the Colonial Club and the New York Athletic Club. According to family history, two of Gillette’s brothers were held in Confederate prisons. His brother, Walter Gillette (see) was a Civil War veteran. He last lived at 240 West 72nd Street in Manhattan. He died of typhoid fever. Section 45, lot 11380, grave 14.

GILLIES, WILLIAM (1834-1916). Private, 20th Infantry, United States Colored Troops, Company G. Gillies, an African-American born in Norfolk, Virginia, was 5′ 8″ with a dark complexion, and black hair and eyes. A farmer by trade, he enlisted at New York City as a private on December 23, 1863, and mustered into the 20th United States Colored Troops (USCT). He was discharged on March 5, 1864, by order of Major General Dix without pay or allowances based on a surgeon’s certificate of disability and disease contracted before entering the service. His name is displayed on the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C., plaque B-37. He last lived on Avenue L in Brooklyn. The cause of his death was Bright’s disease. Section 181, lot 10214.

GILMAN, GEORGE (1832-1901). Private, 170th New York Infantry, Company C. Born in New York City, Gilman enlisted there on September 12, 1862, mustered into the 170th New York on October 7, and was absent and listed as sick when his company mustered out of service at Washington, D.C., on an unknown date. His last residence was 447 Pacific Street in Brooklyn. Gilman died of Bright’s disease. Section 136, lot 28307, grave 108.

GILMAN, HENRY M. (1847-1871). Mate, United States Navy. Gilman entered the Navy as a mate on June 22, 1863, and resigned three months later, on September 30. He was living at 315 Franklin Avenue in Brooklyn when he died of consumption. Section 81, lot 3228.

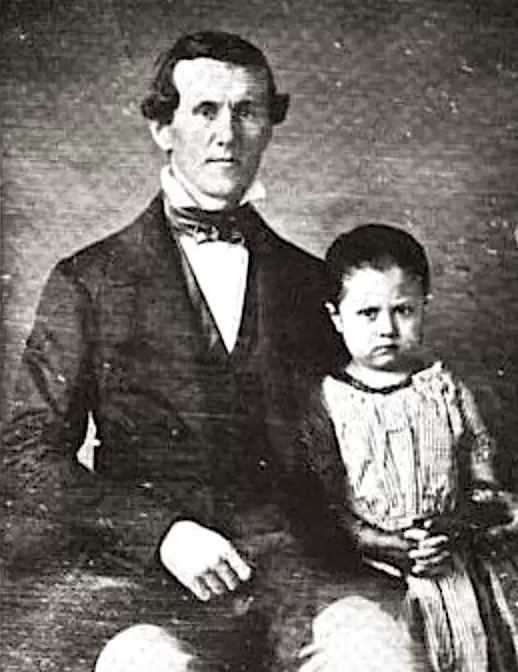

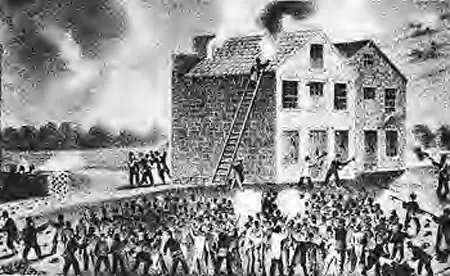

GILMAN, WINTHROP SARGENT (1808-1884). Abolitionist. Born in Marietta, Ohio, his paternal ancestry could be traced to Exeter, New Hampshire, where his father graduated first in his class at the renowned Phillip’s Exeter Academy. According to his obituary in The New York Times, he was educated in New York City and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and returned to the West in 1830, opening a wholesale grocery business in St. Louis, Missouri. He was known as an “original abolitionist,” but was not an outspoken one. In 1837, Gilman allowed the abolitionist newspaperman Elijah Parish Lovejoy to hide his printing press in one of Gilman’s warehouses in Alton, Illinois. A mob soon burned the building and killed Lovejoy. Gilman wrote a letter to Henry Tanner, a leading abolitionist in Alton, describing that event:

It is well known that in 1836, the abolition of slavery in the Southern States became a subject of intense feeling. As the eyes of the Northern people opened to see the evils of slavery they began to discuss the subject and form Abolition societies. This provoked the hostility of the South, and the right of discussion, the right of petition on the subject, and the right to send Abolitionist publications through the mails were denied….

After noting that Lovejoy lost two presses and calling him a conscientious Christian, able writer, and a moderate by abolitionist standards, Gilman had agreed to let him store his press in Alton:

I resided at Alton at that time, though I was a not a member of an abolition society. I knew nothing of this fourth press until after it was shipped, but opened our warehouse at midnight, November 6, 1837, and had it snugly packed away in our third story, guarded by volunteer citizens with their guns. All arrangements were made with the Mayor’s sanction. He told us he would make us special constables and would order us to fire on the mob if we were assailed. The result is a matter of history.

Gilman refused to give up the press, and said it was a mob with “arms and hootings, with tin horns blowing, and plenty of liquor flowing among them.” After Lovejoy was killed, the press was surrendered, and those who guarded it escaped. Following these riots, Gilman moved to New York City where he entered his family’s banking business, Gilman and Sons at 47 Exchange Street (later moving to 62 Cedar Street) in Manhattan. That firm dealt in many real estate and other ventures across the country.

In private life, he loved science and built an observatory at his home in Palisades, New York, where he studied meteors. His family had numerous connections to education, associating with the Browns in Rhode Island who were the founders of Brown University there. Winthrop Gilman’s son, Arthur, was a founder of Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He died of meningitis. His widow, Abia Swift Lippincott Gilman, narrowly escaped burning to death in 1900 from a gas-light torch in front of the Scribner mansion on East 38th Street. Section 118, lot 11666.

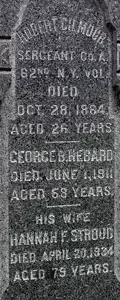

GILMORE, ROBERT (1838-1864). Sergeant, 62nd New York Infantry, Company A. Born in New York City, he was a carpenter by trade. He enlisted as a private on February 1, 1862, and mustered into the 62nd on February 14. According to his muster roll, he was 5′ 5″ tall with blue eyes, sandy hair and a light complexion. He re-enlisted on February 19, 1864, was wounded on May 6, 1864, at Wilderness, Virginia, and had an intra-regimental transfer to the Field and Staff on August 20, 1864, at which time he was promoted to sergeant. Wounded in battle by a gunshot to the right hip at Cedar Creek, Virginia, on October 19, 1864, he died nine days later, and was interred on November 15, 1864. Section 206, Lot 31234, grave 10.