In 2002, Green-Wood restored and rededicated New York City’s Civil War Soldiers’ Monument here on Battle Hill. Inspired by that rededication, Green-Wood launched its Civil War Project to identify what were expected to be several hundred Civil War veterans interred here. But, in the thirteen years since then, hundreds of volunteers have discovered an amazing 5,000 people buried at Green-Wood who played a role, either military or civilian, in the Civil War. More Civil War veterans are interred at Green-Wood than at any cemetery north of the Mason-Dixon Line. For each of these individuals, volunteers have researched and written a biography, supplemented by photographs of their gravestones and their portraits. Remarkably, of those 5,000, 2,200—44%–were in unmarked graves. So applications were made to the Department of Veterans Affairs for gravestones or bronze plaques to mark those graves. Almost all of those markers have now been installed by cemetery staff, free of charge. Green-Wood’s Civil War Project continues to do follow-up research on these 5,000 and to discover more and more individuals—all the while honoring the service and sacrifice of these men and women.

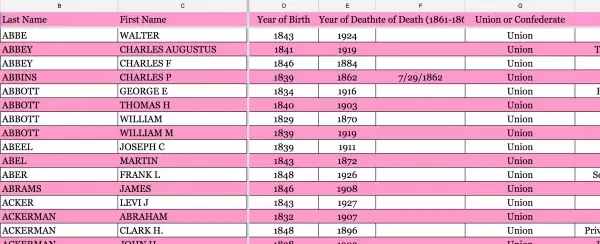

As the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War approached earlier this year, our Civil War Project volunteers created spreadsheets from these 5,000 biographies, featuring year of birth and death, date of death for those who died 1861-1867, whether they served the Union or the Confederacy (we have found 78 Confederates!), civilian occupation, highest rank achieved, regiment number and the state that organized that regiment, branch of military, birthplace, where and when captured, where and when wounded, place of death from disease or battle during the war, last residential address, and cause of death, as well as the section, lot, and grave numbers at Green-Wood.

Philip Lehpamer is one of Green-Wood’s longtime volunteers. He is a retired life and health insurance actuary, a Fellow of the Society of Actuaries, and a member of American Academy of Actuaries. So, as you might imagine, when he heard about this spreadsheet, with its extensive data pertaining to 5,000 19th-century lives, its large sample size and details of their lives not often found elsewhere, he was intrigued. He brought his professional training to bear, working with the data in these spreadsheets.

After his review of this data, these are the conclusions he reached:

1. The average age at death of Civil War army veterans is correlated to the highest attained military rank, with the higher ranks having better average longevity.

2. Veteran mortality was uniformly worse than the available population mortality across all ranks except for the rank of private during the time period 1916-1935.

3. The officer ranks had better mortality than the private rank in the first four decades after the Civil War, except for non-commissioned officers (sergeants and corporals) during the time period 1886-1895.

And here are Philip’s observations:

The three results obtained in this study may not hold for Civil War veterans buried in other cemeteries because of the demographics of the soldiers. In particular, Green-Wood Cemetery veterans are mainly Union troops (less than 2 percent fought for the Confederacy), and only a few are identified as African-American soldiers, two factors that would have affected subsequent mortality.

If the Civil War adversely impacted the long-term longevity of surviving soldiers throughout the country similar to Conclusion 2 of this study, then perhaps the actual length of military service during the war years for each soldier is a factor in the study. In particular, perhaps the 252 Privates who survived into the last two decades of the study and then showed better mortality than the population and the officer group had limited exposure to the actual war; hence, less stress to carry forward and greater longevity. There is enough information in the Green-Wood archives to answer this and related questions concerning the impact of the Civil War on its veterans.

In August 2008, Department of Defense actuaries reported significantly higher mortality rates among active duty retirees compared to reserve retirees, with the disparity stretching back decades. In any given year the death rate for active duty enlisted retirees age 60 and older was 20 to 25 percent higher than for comparable reserve enlisted retirees. Active duty officer retirees who are 60 and over have about 10 percent higher mortality than retired reserve peers. With respect to the overall population, all retired officers and retired reserve enlisted soldiers had better mortality, but for retired active duty enlisted, their mortality was about even with the overall population.

The results of this study surprised many individuals and raised several questions, ranging from the quality of medical care active duty retirees were receiving to the adverse long-term impact of military stress on the life of a soldier; this latter being exactly the point of view expressed in the late 19th century as the deaths of Civil War soldiers began to be investigated. Why active duty retirees have had worse mortality than their reserve counterparts in recent times may still be under investigation. But the mortality experience of Green-Wood Civil War veterans as shown in Table 4 documents a long-term adverse impact—even years after the conflict ended. Given the improvements in medical knowledge and technology, one would like to think those impacts are behind us, but apparently that is not the case.

Philip Lehpamer’s study of this data was published in full in the July/August issue of Contingencies, the magazine of the American Academy of Actuaries. You will find it, in its entirety, here.

Thanks to Philip Lehpamer for sharing his work! It helps us understand the lives of these individuals and the Civil War that they lived through.

A wonderful project and interesting use of the big data your very humanistic project generated when you had tabulated your results. Innovative use of your resources, as always, you are a model for how to use a cemetery

Thanks!