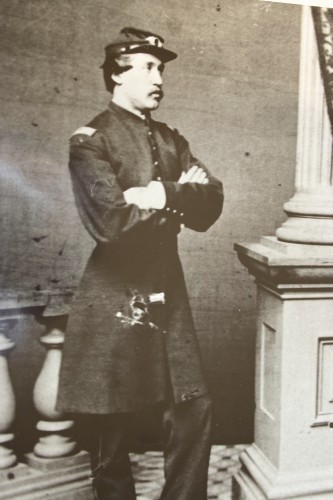

I feel like I know Henry Augustus Sand pretty well. Not that I ever met him. After all, he died in 1862. But, I have read a great deal about him, his service to his country, and his ultimate sacrifice. He is, of course, interred at Green-Wood. I told his noble, heroic, yet sad story at length in my book, Final Camping Ground: Civil War Veterans at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, In Their Own Words. His descendants were wonderfully cooperative in doing that–they shared his letters, those of other members of his family, and an extraordinary memorial book that his sister put together, featuring her own 1863 paintings of the Antietam battlefield where he was mortally wounded, the barn to which his shattered body was carried, and the Otto Farmhouse, where he struggled to live, but ultimately died.

An account of his death, written in 1866, described him as “a man of the highest & finest moral character–well-educated, elegant & accomplished” and his death as “one of the noblest to the cause of the Republic.”

Henry Augustus Sand, born in New York City in 1836, was well-educated (by one account, he studied for two years in Switzerland), from a well-off New York family, when he went off to fight for his country during the Civil War. With the fateful last battle of his life–the Battle of Antietam–rapidly approaching, Henry wrote, just 12 days before it: “We must soon have a very superior force and as we are at least equal to the enemy in courage and endurance, I don’t see how they can head us. Numbers do not always avail–it is the determination to win or die, that brings victory.”

At the Battle of Antietam, Henry’s regiment, the 103rd New York Volunteer Infantry, crossed Antietam Creek and advanced uphill towards the Confederates. After the color bearer of the 103rd was shot down, Henry, according to an account written in 1865, “rushed forward, extricated our flag from his dying grasp & bore it aloft. He ran along the line, waving the flag, inspiring the men with courage & then advancing several feet, firmly planted it, calling to his men to come up to that. He turned to them with an encouraging smile, –when the next instant he fell to the earth, shot through the thigh by a rebel sharpshooter.”

While lying badly wounded on the battlefield, his leg shattered, Captain Sand took out pencil and paper and wrote the most moving Civil War letter I have ever read to his mother back home:

Dear Ma,

Here I lay on the field, shot through the thigh. My wound is painful but not mortal I believe–however I send you these lines to bid you all goodbye in case I never see you again.–I hear our men cheering & I hope the day is ours–if we only have a great victory I am contented. Goodbye. My love & kiss to all.

Your loving son,

Henry

As Captain Sand described in his letter of September 22, five days after, “I was wounded in the inside of the left leg a few inches from the hip. The bone is shattered, but not broken I believe. The ball lodged & was extracted from the other side of the leg. The wound is extremely painful & I see no prospects of being moved from her for a long while.”

Henry’s mother, accompanied by his younger brother, came to the Antietam battlefield, in hopes of comforting Henry and nursing him back to health. This from an 1865 account: “. . . his mother still clung to hope and could not believe a life so precious was soon to close. On the 30th Oct at 11 o’clock in the evening, after 6 weeks of suffering he sank to rest, his hand clasped by that tender mother, who had been his friend and guide through life. She felt that she had laid her most precious gift on the alter of her country. Thank God, the sacrifice had not been in vain.”

Soon thereafter, Major Benjamin Ringold of the 103rd wrote to Captain Sand’s father, expressing his regrets for “the loss of a so highly esteemed friend, comrade and gallant soldier.” Major Ringold reported that the commissioned officers of the 103rd, to honor Captain Sand, had been ordered to wear symbols of mourning on their uniforms for 30 days, and it was further ordered that a symbol of mourning was to be attached to the regiment’s flag standard, “which he most gallantly bore forward, and under which he fell, as a just tribute to the memory of the hero, patriot and brother officer.”

Quite a story! But there was more to come.

I was recently in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. On a Wednesday two weeks ago, I drove down there, stopping along the way at the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg. Amazing items on display! On Thursday, I took part in an all-day event organized by the Center for Civil War Photography. We had behind-the-scenes access to the photographic collections of the Adams County Historical Society and the National Parks Service collections. It was fascinating!

I figured that, while I was in Gettysburg, I would stay until Friday and spend that day with a battlefield guide. So I went out with a guide who Sue Ramsey–our wonderful researcher out in California who is doing research on our Civil War veterans from 3,000 miles away–had recommended. Gary Kross took me out to the East Cavalry Field–I had never been there before–and I heard the Custer story out there. I saw the monument to the Michigan Cavalry. Quite impressive–and pristine land, looking like it was July 3, 1863. One of our Green-Wood guys was with Custer that day–James Birney, who had his horse shot out from under him, used the flag staff that he was carrying to defend himself, then was slashed in the head with a saber and badly wounded, captured, then escaped. Custer thought so much of Birney that he gave him an inscribed presentation sword for his bravery at this battle.

Gary also showed me the area where the hospitals were set up after the battle–and the house behind which Major General Dan Sickles’s leg was amputated. We then drove through the village of Gettysburg–and Gary suggested I check out the Horse Soldier store–it had acquired, he reported, much new material for sale. I have been in there a number of times and they have great Civil War items: original photographs, swords, muskets, and all sorts of one-of-a-kind items. I had already thought about going in there–but once Gary recommended it, I just had to go.

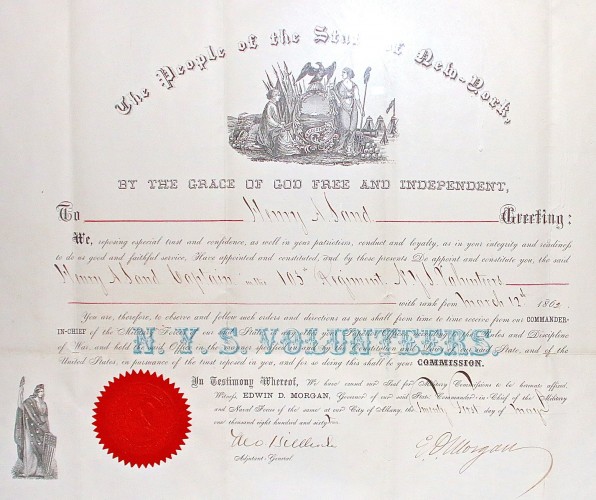

Well, as I walked around the store, a framed commission–a document appointing an individual to an officer’s rank during the Civil War–caught my eye. Remarkably, it said “Henry A. Sand” on it. That, I thought, just might be Green-Wood’s Henry Augustus Sand! But, as I read the handwriting on the commission, it looked to me like the rank appointed to was chaplain. That struck me as odd–even in an army of several million, how many men would have the name that I recognized: Henry A. Sand? Then I saw it was a commission in the 103rd regiment–the regiment I knew our Henry had served in so gallantly. So looked again at the rank. I had misread it; it said captain, not chaplain. It was indeed for our Henry!

I asked to look at it and that’s when I learned that the lot included a binder with letters in it: one by Henry, reporting back to his family on the 103rd’s first battle, in April 1862, at Fay’s Plantation in North Carolina. Two by his mother, Isabella, to her husband, back in New York City, describing the efforts to save the life of their eldest son, Henry. And 3 letters from his brother, Theodore, written from Pennsylvania, while in militia service with the 22nd New York, during the June-July 1863 invasion by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, under the command of General Robert E. Lee.

So I called Green-Wood’s offices, determined that there was an Isabella in the same lot with Henry (his mother’s name, who wrote two of the letters)–and asked for permission to buy the lot. Permission granted!

According to Henry’s account in his letter of that skirmish in April, 1862, 80 men of the 103rd were attacked by 260 rebels of the 19th North Carolina Cavalry. Henry had not been in that fight: “I begged the Colonel to take me along but he wouldn’t do it so I had to remain in the rear. I wish the secesh would come down here. We are ready for them and “spitting” for a fight.”

Two letters in this lot, from his mother, describe her efforts to save her son after his wounding at Antietam. They offer a perspective rarely seen. On October 13, 1862, almost a month after her beloved son had been wounded, she wrote to her husband, in part: “Here you can imagine we have many anxious weary moments. We have now a good physician, who attends Henry faithfully and does every thing in his power for him but he suffers a great deal. Particularly from a sore on the lower part of his back which is difficult to reach and to dry up, causes great pain.” Almost two weeks later, on October 26, she wrote that Henry was ” . . . now comfortably situated, at least, as comfortable as he can be with his fractured limb. . . . The Doctor has taken away several little pieces of bone, which seem to have been literally mashed in the wound, that is, the lower wound where the bone came out, has discharged quantities of matter and he seems much easier.” She had been told by Dr. Goulet, “an excellent surgeon,” that “he has every hope of his entire recovery, not however without a slight lame hip.” Henry, she continued, “grows thinner daily but the doctors are not alarmed and say it is always so after lying so long.” The doctors were giving Henry sherry and “when in extreme pain, brandy.” Henry was “cheerful and hopeful.” But it was not to be; just four days later, on October 30, Henry Augustus Sand died at the Otto Farmhouse, where he had been taken after his wounding and where his mother, and the attending doctors, had tried their all to save him.

Three days later, on November 2, Captain Sand was interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. Here are the lines, written by a friend, that were read as his grave that day:

Breathe not a whisper here,

The place where thou last stand is hallowed ground.

In silence gather near this upheaved ground

Around the soldier’s bier.

Here Liberty may weep,

And Freedom pause in her unchecked career,

To pay the sacred tribute of a tear

O’er the pale warrior’s sleep.

That arm, now cold in death,

But late on Glory’s field triumphant bore

Our country’s flag: the marble brow once wore

The victor’s fadeless wreath.

Rest soldier, sweetly rest.

Affection’s gentle band shall deck thy tomb

With flowers; and chaplets of unfading bloom

Be laid upon thy breast.

This is Henry Sand’s gravestone, as it looks today:

Green-Wood is now the proud owner of these historic and evocative captain’s commission and Sand family letters. They will help us tell the story of Captain Henry Sand, who had so much to live for, but who sacrificed himself for his country and its cause. These items will be displayed in our Historic Chapel in an exhibition about our Civil War veterans, “Honoring Their Sacrifices,” next Memorial Day Weekend, for our commemoration of the 150 anniversary of the end of the Civil War–150 years after the battlefield carnage stopped.