Every once in while something of great interest–though not great monetary value–comes out of someone’s drawer or closet and finds its home. So it is with the little piece of paper discussed below.

Since 2002, volunteers with our Civil War Project have identified 5,000 veterans at Green-Wood and written a biography for each of them..

One of them is Frederick C. Kohler. Here’s his biography:

KOHLER, FREDERICK C. (1843-1884). Private, 1st New York Engineers, Company H. A native New Yorker, he enlisted and mustered into Company H of the 1st New York Engineers on April 1, 1865. He mustered out on June 30, 1865, at Richmond, Virginia. He last lived at 2390 First Avenue in Manhattan. Section 147, lot 22161.

Not one of our most fascinating histories. A private, who enlisted very late in the Civil War–just 8 days before Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia, effectively ending the war. Kohler was not wounded or captured; his was uneventful and brief service, as far as we can tell.

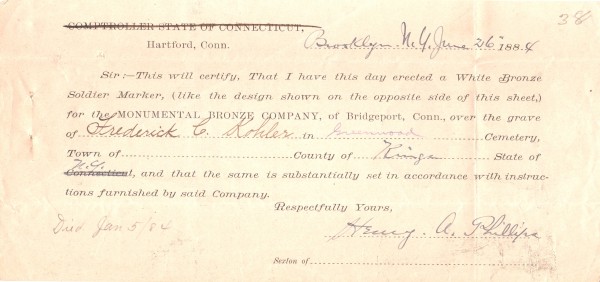

But what is fascinating is this document that relates to Frederick C. Kohler and which I recently purchased for The Green-Wood Historic Fund’s Collection. Here’s its front:

This is the report of Henry A. Phillips, dated Brooklyn, New York, June 26, 1884, that he had “this day erected a White Bronze Soldier Marker, (like the design on the opposite side of this sheet,) for the MONUMENTAL BRONZE COMPANY of Bridgeport, Connecticut, over the grave of Frederick C. Kohler in Greenwood (sic) Cemetery . . . .” There is a handwritten notation at lower left that Kohler had died on January 5, 1884; less than 6 months later, he had his soldier’s marker. Note that most of the installations of these Civil War markers seem to have been done in Connecticut and for the State of Connecticut: this form, at its top, is addressed to the COMPTROLLER OF THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT; that has been crossed out here, and the state in which the cemetery is located, printed on the form as Connecticut, also has been crossed out and “N.Y.” written in.

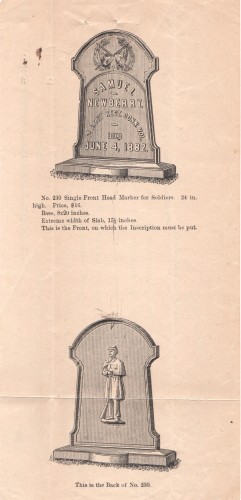

And here’s the back of the same document:

So I went out onto Green-Wood’s grounds to see if this marker, 130 years later, is still where Henry A. Phillips erected it. And there it was:

Note the condition of the marker: aside from a bit of a tilt, caused by a shifting of the ground, it is in excellent shape–as readable today at the day it was installed. And what is particularly remarkable is that it has gone unpainted and untreated since the date of its installation. The Monumental Bronze Company marketed cast zinc cemetery markers (it preferred to call them “White Bronze”–though they were in fact zinc, not bronze) as a scientific breakthrough, but some cemeteries, including Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the first of America’s rural cemeteries, banned them with the rationale that they were too industrial and mass produced. Other cemeteries refused to allow cast zinc, fearing that that material would require new coats of paint, as iron had, every few years. That clearly was not the case with these zinc markers; no paint has been applied to this marker since the day it was installed. For more on cast zinc monuments, see my blog post from 2009, “Zinc, You Think?” And, you will find more about the Monumental Bronze Company and its wonderful monument at Green-Wood, “Our Drummer Boy,” here.

Here is the back of the Private Kohler’s cast zinc monument:

Green-Wood has about 60 cast zinc monuments across its grounds–one of the largest collections of such markers anywhere. Cast zinc was a wonderfully versatile material; we have angels, a drummer boy, a lyre, and many other forms. All you needed was to carve the design in wood; the wooden form then was pressed into wet sand, creating a mold, then molten zinc was poured into the sand mold and voila! I would estimate that Green-Wood has about half a dozen Civil War soldier markers like this one. It stands today, as it has since 1884, over Private Frederick C. Kohler’s grave. And now, with this installation slip, we know a bit more about it.