With over half a million people interred at Green-Wood, and tens of thousands of monuments across its grounds, Green-Wood has connections to many subjects. So it is with “The American West in Bronze, 1850-1925,” an exhibition that has just opened at The Metropolitan Museum: many of the sculptors whose work is on display also created magnificent sculptures at Green-Wood.

The exhibition features 65 bronze sculptures (by 28 artists) and 3 paintings. As the press release states, this exhibition “. . . explore(s) the aesthetic and cultural impulses behind the creation of statuettes with American western themes so popular with audiences then and now . . . .”

The press release makes an interesting point about bronze as a material for sculpture: The development of fine art bronze casting in America is traced through the works displayed in this exhibition. Unlike marble, which was quarried in Europe and shipped across the ocean at great expense, bronze—an alloy composed of copper, with lesser amounts of tin, zinc, and lead—became readily available in the United States following the establishment of the earliest art bronze foundries around 1850. Because of its accessibility and relatively low cost, bronze came to be considered both as an American material and a democratic one. The exhibition will include many compositions that would not be possible in marble, featuring such extremely challenging depictions in bronze as the astonishingly realistic representation of a bison’s furry coat or a fleet-footed horse and rider suspended in mid-air, supported only by a trailing bison hide. Bronze was particularly well suited to the complex compositions, textural variety, physical action, and narrative detail of these western works.

The exhibition includes this sculpture by Solon Borglum (1868-1922):

The press release for the exhibition describes Borglum:

Solon Hannibal Borglum, who was born in Ogden, Utah, and received his artistic training in Cincinnati and Paris, looked at the subject of horses afresh, emphasizing their essential role in the American West for hunting, ranching, fighting, trading, and transit. His sympathetic portrayals of horses enduring the challenges of frontier life were supplemented by poignant depictions of intense human-equine bonds, whether an Indian shielding himself behind his horse in On the Border of the White Man’s Land (1899, Metropolitan Museum) or a cowboy and his mount huddled together in The Blizzard (1900, Detroit Institute of Arts).

“The American West in Bronze” was curated by Thayer Tolles, Marica F. Vilcek Curator, American Paintings and Sculpture, The American Wing, and friend of Green-Wood (her essay, “‘Adorning the Last Home of the Loved and Lost’: Green-Wood as Sculpture Garden,” appears in our recently published book, Green-Wood at 175: Looking back/Looking forward), and by Thomas Brent Smith, director of the Petrie Institute for Western Art of the Denver Art Museum. As Tolles notes about Borglum’s “Bulls Fighting,” “[t]he low horizontality . . . emphasizes the intensity of the clash between the wild Texas longhorn and the stouter shorthorn.” Borglum grew up in the West; his personal experience there undoubtedly affected his work.

A great work by Solon Borglum–brother of Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor of the huge presidential sculptures on Mount Rushmore–is at Green-Wood. “The Angel of Death” is in the Schieren Family Lot along Fir Avenue between Grape and Dale Avenues:

Here is Borglum’s signature on “The Angel of Death:”

Remarkably, “The Angel of Death” has a face–which can be seen if you get down on your hands and knees and look up under the cloak:

Both Charles Schieren and his wife died within hours of each other in March, 1915. He had been ill for two years; his wife, who had been trying to nurse him back to health, herself became ill and died the day after he did. The family chose an understandably somber subject, “The Angel of Death,” for the monument in their lot.

A bronze by sculptor Frederick MacMonnies, from the collection of President Theodore Roosevelt, is also featured in the exhibition.

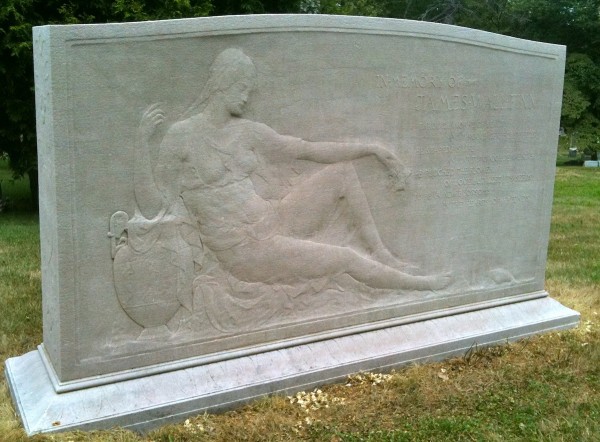

MacMonnies (1863-1937) was supposed to be interred at Green-Wood in his family’s lot there. On the morning of his funeral, his grave there already had been dug. But, just before the funeral cortege was to arrive, his wife called and cancelled his burial at Green-Wood. He was interred elsewhere and now sadly lies in an unmarked grave. But two of MacMonnies’s great sculptures adorn Green-Wood. This is the monument he sculpted, in low relief, for his friend and fellow artist, James Wall Finn, who was a muralist for Tiffany Studios:

You will find an earlier blog post on Finn’s monument here. And, here is MacMonnies’s sculpture, “Civic Virtue,” which was brought to Green-Wood a year ago, and is now on permanent loan from New York City:

If you would like to read more about how “Civic Virtue” wound up at Green-Wood, click here.

Henry Kirke Brown (1814-1886) is another sculptor whose work appears in the exhibition:

Brown has three sculptures at Green-Wood–two bronzes and a marble carving. Certainly the most important of those three–both from the standpoint of it being a game changer for Green-Wood in attracting visitors and sales, and because it is one of the first large bronzes cast in America–is the heroic bronze of De Witt Clinton:

The De Witt Clinton Monument at Green-Wood is one of the first large bronzes cast in America–and the second-oldest still in existence–only the equestrian statue of President Andrew Jackson that graces Lafayette Square Park in Washington, D.C., opposite the White House, is earlier.

Here is a detail of Brown’s other bronze at Green-Wood–a memorial to William Satterlee Packer (for whom Packer Institute on Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights is named):

And here is Brown’s sculpture for the Cozzens family:

Sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward was one of the leading American sculptors of the 19th century. His “The Indian Hunter” dates from 1860:

Several years ago, Lewis Sharp, an expert on Ward, confirmed my suspicions that the Fogg Brothers Monument at Green-Wood is by John Quincy Adams Ward:

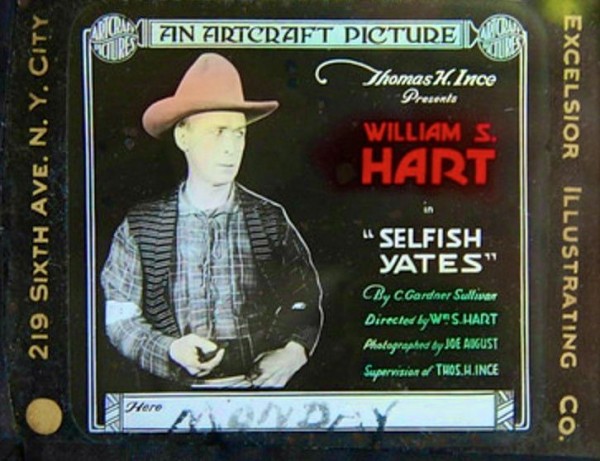

And, finally, one of the bronzes in the exhibition is a portrait of a Green-Wood permanent resident, rather than by a sculptor who has a Green-Wood connection. William Surrey Hart was a giant of silent movies. Here is the bronze portrait of him:

And here is William S. Hart, in a coming attraction slide for one of his silent movies. These slides were used in movie theaters to update the audience on what was about to play there.

The exhibition, “The American West In Bronze, 1850-1925,” which has just opened, runs through April 13. There is much to see there-go visit!