A landmark exhibition, “Photography and the American Civil War,” is now open at The Metropolitan Museum. Featuring 200 photographs, some classics, some obscure, the exhibition is spectacular. If you have any interest at all in photography and/or history, don’t miss it.

Photography and the Civil War go hand in hand. Much of what we know of the Civil War is from the thousands and thousands of photographs of it. Photography, still in its infancy in 1860, emerged during the Civil War as a key medium–photograph would, for the first time, document a great conflict from its very beginning to its very end.

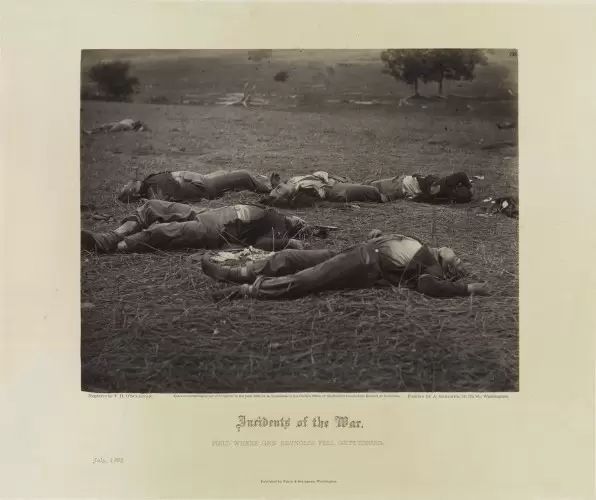

On October 20, 1862, a reporter for The New York Times wrote about the remarkable images of battlefield death then being shown at photographer Mathew Brady’s New York City gallery–images the likes of which had never been seen before:

Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it…Here lie men who have not hesitated to seal and stamp their convictions with their blood,—men who have flung themselves into the great gulf of the unknown to teach the world that there are truths dearer than life, wrongs and shames more to be dreaded than death.

The Met’s exhibition, by Jeff L. Rosenheim, curator in charge of the Museum’s Department of Photographs, is multifaceted. It features Civil War photography in many aspects: portraiture, documentary photographs of the underlying causes, the dead on the battlefield, and the price that was paid by the wounded.

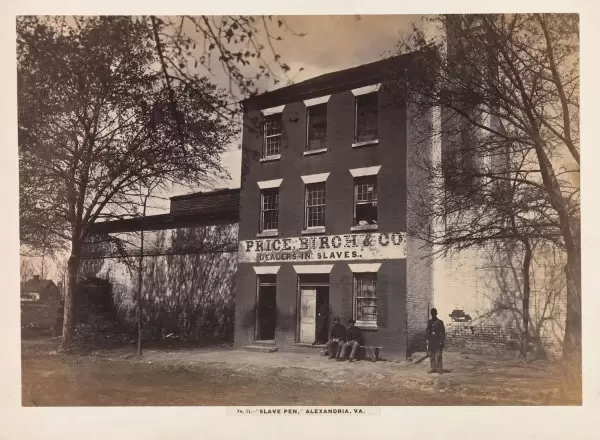

The prelude to the Civil War is dealt with. So, we see a documentary photograph of a Virginia slave pen:

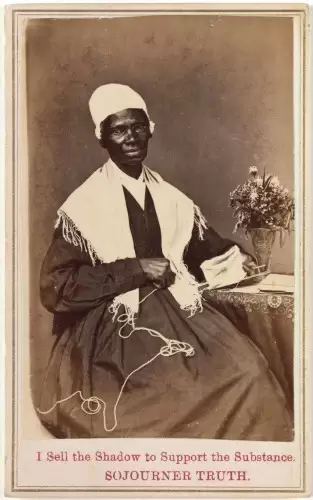

A carte de visite (standard size of a cdv is 2.5 x 4 inches) portrait of Sojourner Truth, ex-slave and abolitionist, is great, not only for the capturing the image of this important historic figure but also for the text printed on it:

And, this campaign button for Abraham Lincoln, Republican candidate for president of the United States, whose election touched off secession and the Civil War, is a gem.

The exhibition design is outstanding. Many of the photographs taken during the Civil War were stereoscopic views that, through two lenses, could bring the war home in 3D. But, for too long, exhibitions have, by and large, avoided showing these images in their 3D glory. The Center for Civil War Photography, of which I am a member, has pioneered bringing these 3D images back into public forums, creating many 3D exhibitions across America in the last few years. Here, the Met does it right, using several wooden tabletop Beckers viewers (designed and patented by Alexander Beckers, who is interred at Green-Wood–see this earlier blog post about him) to display these photographs. My one regret in this regard–though Beckers’s name and patents are visible on the small original metal tags, no mention of him, and the substantial contribution he made to Civil War Photography, is made in the exhibition. And, creatively, there is a electronic viewer, with a 36-image slide show, mounted inside a Becker viewer, so that two people can watch the show simultaneously. The exhibit designers have also used canvas on the walls of the galleries to give visitors the impression that they are in the tent of a photographer who had set up his business near the camp of a Civil War army–a very nice touch.

Throughout the exhibition, great respect is shown for the photographs. Classic large format photographs from Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of War and George N. Barnard’s Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, both released in 1866 are given their due.

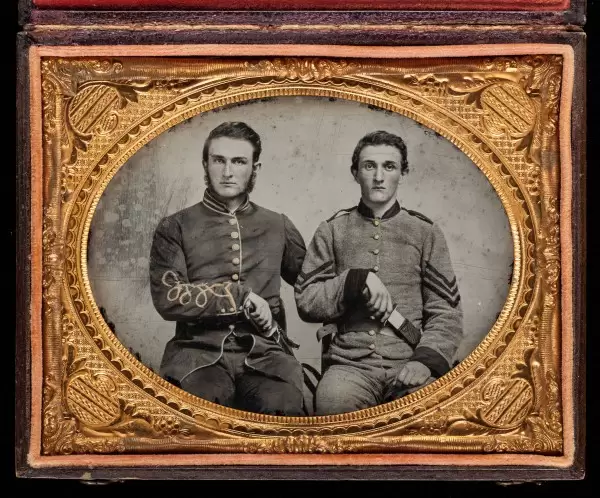

In addition to images from the Met and other museums, some great private collections were tapped for unique images:

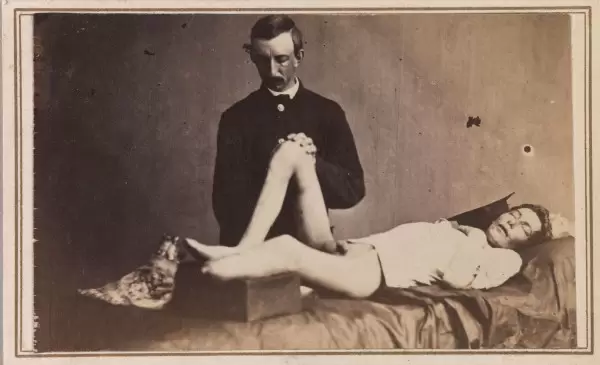

And, what of the toll of the war? What of the 750,000 dead? What of the wounded? This rare photograph, and many others, document the injuries suffered by the combatants:

And, cleverly, cartes de visite photographs, which were printed on paper that was then glued to a heavier card stock as a calling card (images of political leaders, general, and soldiers were collected by the public much in the way we might collect baseball cards today). The largest purveyor of these cdvs was the E. and H.T. Anthony Company; Edward Anthony (the “E.” in the company name) is interred at Green-Wood–here’s a blog post on him), are displayed so that both the front and the back of the cards can be seen. A great touch–when, for instance, the caption next to one of the photographs states that a soldier in a group photograph wrote the names of his comrades on the back, you can see both the photograph on the front of the cdv and his handwriting on the back. Also visible are the revenue stamps on some of the backs–used as a tax on the sale of photographs aimed at raising money for the Union war effort. And, identifying names, some contemporary with the issuance of the photographs, some written by later researchers or collectors, can also be seen on the backs.

The exhibition runs through September 2. Go see it!

The Civil War is, in fact, the first major conflict to be so thoroughly documented. Not only did photography come into its own as a tool of journalism, but the fact that nearly all the combatants on both sides were literate — a condition that had never before occurred — created hundreds of thousands of letters and diaries. In short, there is so much fascination with the Civil War because there are so many materials to fuel it. And we owe those soldiers our respect, since more Americans died in the Civil War than in any other conflict.

Well said!