Over my years, I have learned that often one thing leads to another. That happened again recently. A few months ago I purchased a carte de visite photographic portrait on the front of which was written, “Alexr. Saeltzer. Archt.” I recognized that name as that of a 19th-century New York City architect (who designed the building that is now the Public Theater on Lafayette Street) and discovered that he and his wife are interred at Green-Wood. This is the post, “An Important, But Long-Forgotten, Architect,” that resulted from that discovery.

And that post led to Michael J. Lewis, a professor of art history at Williams College, who contacted me to report that he had read my blog post on Saeltzer. Professor Lewis added that he was the biographer of Frank Furness, the famous Philadelphia architect, and that one of his specialties is German architects who immigrated to America. Michael has been researching Saeltzer and others for years. During the course of his research, Professor Lewis had come across two photographs at the the Royal Institute of British Architects Library in London identified as works at Green-Wood. As Professor Lewis explained, “The other item I wanted to call attention to was the work of the architects Charles Gambrill and George Post in your cemetery. They designed the two tombs shown here . . . . Designed ca. 1864/66, they were felt to be important enough to photograph and send to the Royal Institute of British Architects.” Professor Lewis explained his theory on how these photographs of Green-Wood wound up in London: “My suspicion is that [architect and teacher Richard Morris] Hunt dropped off the photographs when he passed through London on his way to visit the Paris World’s Fair of 1867. He seems to have asked his students [including Post and Gambrill] for samples of their recent work, which would explain why only works prior to 1867 or so are included.”

Here is the first of the RIBA photographs that Professor Lewis sent me:

I immediately recognized the LaFarge Mausoleum. John LaFarge was one of America’s greatest 19th-century artists: painter, pioneer of American stained glass (and competitor of Louis Comfort Tiffany, also at Green-Wood), and a great designer of mosaics. I had long had my eye on this mausoleum–it clearly was something special with its carvings and its mix of materials: brownstone, slate, and pink granite columns. In fact, I had contacted several LaFarge experts a few years ago to ask if it might be by Grant LaFarge, John’s son, who was an architect. I was told by a LaFarge biographer that that might well be the case. I now learned that that opinion had been in error. Now we knew that it was by George B. Post and Charles Gambrill. Post was one of America’s top architects. He was the architect of the Brooklyn Historical Society, the New York Stock Exchange, the Equitable Life Assurance Building, the St. Paul Building, and the Produce Exchange. Later in his career, Post would be known as “the father of the tall building in New York.” Gambrill would go on to partner with Henry Hobson Richardson in the design of Trinity Church in Boston and the Century Association on 15th Street in New York City. Both were important American architects–it was great to discover their work at Green-Wood.

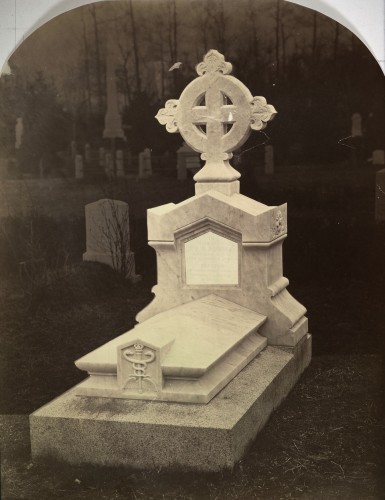

Here is the second photograph Professor Lewis sent me:

This was something of a mystery. Initially, Professor Lewis thought it was a memorial to Charles Gambrill’s sister. I did find one Gambrill in Green-Wood’s records and went out to the lot, near the Catacombs, to take a look at the monument there. But it looked nothing like the memorial in the photograph. I then spoke with Green-Wood’s vice president for operations, Ken Taylor. Ken has worked at Green-Wood for years and knows the grounds better than anyone else. I showed him the photograph and asked if he recognized it. He did not. He then sent an e-mail to all of our workers on the grounds, telling them that the first one to locate this monument on the grounds would be treated to a free lunch by me. Still no luck.

Then we got Andrew Dolkart involved. Andrew is Professor of Historic Preservation at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture. By coincidence, he was working on an essay about Green-Wood’s architecture for our book (to be published in September) celebrating Green-Wood’s 175th anniversary. I told him about Professor Lewis’s discoveries at RIBA. It turns out that Andrew and Michael are old friends. Andrew ordered the above photographs from RIBA. When he received hi res files, he was able to make out the name carved on the above monument: George Bowman. I checked Green-Wood’s database and there was indeed a George Bowman who was interred in 1863. I went out to that lot–and there is was:

As Andrew pointed out to me, there is a similarity in the carved motifs on the LaFarge Mausoleum and the Bowman Memorial, reflecting the influence of their teacher, Richard Morris Hunt:

Both have five petal flower motifs and what appear to be tulip-like flowers. The LaFarge carving is crisper and more industrial.

But what of the caduceus, a symbol that we associate with doctors, carved at the front of the Bowman Memorial? Was Bowman a doctor? I did some research and discovered that the caduceus was a symbol of commerce in the 1860s, when this monument was designed–and the caduceus was not associated with medicine until later in the 19th century. I researched Bowman–he was a clerk, then a partner, in mercantile firms on Wall Street. Commerce! Made sense!

Professor Lewis gives us some perspective on the importance of our discoveries:

It is surprising how little we know about the designers of the great monuments in our cemeteries. The designers are almost never named in the newspapers, and unless the papers of the architect survive (which they rarely do), it is virtually impossible to know who designed a tomb. This is why the discovery of the authorship of the LaFarge and the Bowman monuments is so important. Not only were George Post and Charles Gambrill architects of national prominence, but these two monuments are their earliest known works, designed in the Neo-Grec style they had learned from their mentor Richard Morris Hunt. This radically abstract classical style had just been introduced to the American public by their friend and atelier mate Henry van Brunt in an influential 1861 essay in Atlantic Monthly called “Greek Lines.” It may well be that Gambrill & Post’s monuments are the first major works in the Neo Grec built in America, which is why this is one of the most exciting discoveries in American architecture in some time.

And one final twist. I asked Frank Morelli and his great Green-Wood restoration team to go out and fix up the Bowman Memorial. The stones had shifted in the century and a half that they had been out there. So Frank and his men realigned the stones and cleaned them and several other monuments in the Bowman Lot. They lifted the stones and moved them back into alignment.

Finally, here’s what George B. Post’s and Charles Gambrill’s Bowman Memorial, and the Bowman Lot, look like today:

The story is fascinating, but it includes a colossal error: the old Custom House on Bowling Green was designed by Cass Gilbert, not George B. Post. It was Gilbert’s first commission in New York and launched his career as a nationally prominent architect. His local work also includes 90 West Street, the Brooklyn Army Terminal and, of course, the Woolworth Building.

Post did design the handsome Produce Exchange, which faced Bowling Green just across Broadway from the Customs House. Alas, it was demolished in 1957 and replaced with the an utterly undistinguished office building, 2 Broadway. (Well, it does have a large mosaic by Helen Frankenthaler over its entrance, adding a bit of visual interest.) Today, it’s the headquarters of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Thank you for the correction; as soon as I read your comment I realized my error. However, you characterization of this mistake as “colossal” is a colossal overstatement.