Green-Wood has many great stories. But few, if any, can match the drama of that of the Civil War Prentiss brothers: “Two Brothers, One South, One North.” It is an A+ at all levels: two brothers from the border state of Maryland, one who fought for the North, the other for the South, during the Civil War. And both of whom were mortally wounded within feet of each other as the older brother led an assault on the trenches defended by his younger brother. Plus, none other than Walt Whitman, volunteer nurse and poet, treated both brothers and wrote about them; Whitman estimated that he had cared for 100,000 men during the Civil War, but he only wrote about 50 or so of them. Clifton Kennedy Prentiss and William Scollay Prentiss lie side-by-side at Green-Wood, near our Historic Chapel, next to Valley Water.

So, I was very excited recently when I had a chance to visit the battlefield where the Prentiss brothers were mortally wounded. I was in Virginia earlier this month, attending the Civil War Trust’s annual convention. The Civil War Trust (CWT) is a great private, not-for-profit organization–it has saved 32,000 acres of Civil War battlefields for posterity. Each year, at its gatherings, the top Civil War historians in America lead tours of battlefields, often leading walks across land that has just been saved by CWT.

This year, I went out to Pamplin Park on a tour with its executive director, Will Greene. Will is truly a great tour guide–his knowledge of the entire Civil War is phenomenal (he leads tours all over the country) and his delivery is superb. Pamplin Park preserves Civil War trenches across the ground where, on April 2, 1865, after four long years of war, Union General Ulssyes S. Grant, having been stymied for months by elaborate trenches and fortifications, finally ordered an all-out attack against the miles of lines of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s entrenched Army of Northern Virginia.

Will led us across the route of the attack to the place where Union troops made their breakthrough of the Confederate lines on April 2, 1865–a breakthrough that would culminate, in just one week, in Lee’s surrender at Appomatox Court House, and the effective end of the Civil War. As we stood at the breakthrough spot, Will spoke of the Prentiss brothers:

Just a short distance from this breakthrough spot stands the monument to Major Prentiss’s 6th Maryland Infantry, one of the Union regiments that broke the Confederate line. Its monument was dedicated a year ago, on April 2, 2011, the 146 anniversary of its triumph. Here is the monument:

I have been fascinated by the Prentiss brothers’ story since I was contacted by one of their descendants several years ago. She had heard about Green-Wood’s Civil War Project (which, as of this writing, in ten years has identified 4,800 Civil War veterans who are interred at Green-Wood, has written extensive biographies for each of those men, has searched the cemetery for each of their graves, and has gotten 2,000 gravestones for those who have lain for so many years in unmarked graves) and wanted to share their story. The Prentiss brothers’ story was big news across America in April 1865. And it is still a poignant story today.

In my book, Final Camping Ground: Civil War Veterans At Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery In Their Own Words, published in 2007, I told the story of the Prentiss brothers:

Two Brothers, One South, One North

Petersburg, Virginia · April 2, 1865

Brothers Clifton Kennedy Prentiss and William Scollay Prentiss were born, respectively, in 1835 and 1839, near Baltimore, Maryland.

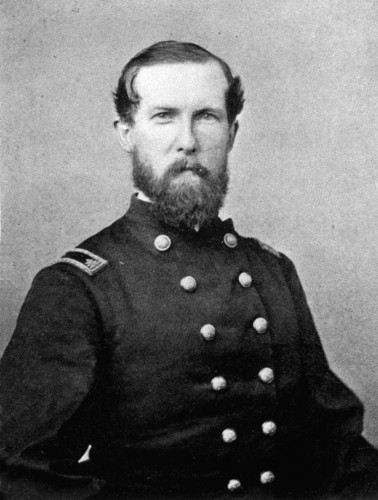

On April 14, 1861, Fort Sumter surrendered to rebel forces and the Civil War began. The next day, President Abraham Lincoln sent out a call for troops to rush to Washington, D.C., to defend the nation’s capital. Only two days later, Clifton Prentiss enlisted in the 7th New York State Militia and served 30 days with that famed regiment before it was mustered out. On March 30, 1862, he enlisted in the 5th Maryland Infantry (Union); he transferred to the Sixth Maryland Infantry as a second lieutenant on July 31, 1862. As the Civil War dragged on, Clifton rose through the ranks, promoted to captain (Chief of Pioneers), major, brevet lieutenant colonel, and finally brevet colonel.

His younger brother, William Prentiss, chose a different path. In March, 1862, William, like his brother unmarried and living near Baltimore, cast his lot with the Confederacy, enlisting as a private in Company D of the First Maryland Infantry. On August 27, 1862, he transferred to Company A of the Second Maryland Infantry.

Though, in the ensuing years, Clifton and William heard occasional rumors that the other’s regiment was camped just over the hill, they did not meet again until April 2, 1865. It was on that date that Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, general in chief of all Union forces, ordered an all out assault along his entire line on the Confederate forces that had been dug in south of Petersburg, Virginia, for almost a year.

According to the report of the field correspondent for the New York Herald, Major Clifton Prentiss led the attack of the 6th Maryland; he was the first officer to enter the enemy’s defensive works that were in that regiment’s front. This claim is supported by General J. Warren Keiffer, the brigade commander who, in his official report, stated: “Maj. Prentiss with a large portion of the 6th Md., was the first to penetrate the enemy works.” But, as Keiffer continued in his report, Clifton’s triumph was short-lived: “After a most bloody struggle he fell mortally wounded very soon after entering the fortifica- tion. Too much praise cannot be given to the officers and men of this regiment.”

On April 10, 1865, this report from a New York Herald correspondent appeared in the Milwaukee Sentinel: Major Clifton K. Prentiss commanding the Sixth Maryland Volunteers, was one of the first officers to enter the rebel works, but was unfortunately shot through the chest . . . we picked up a wounded rebel, who said he was Lieutenant Prentiss, of the Second Maryland rebel regiment. He is a younger brother of the Major whom he has not seen since the rebellion broke out.

Clifton Prentiss had suffered a gunshot wound to his left lung. But his Confederate brother, William Prentiss, defending the very fortifications Clifton had attacked, had also been wounded, struck by a shell fragment above his right knee. John R. King, writing “Sixth Corps at Petersburg. Its Splendid Assault, Which Broke the Main Line of the Rebels” in the April 15, 1920 National Tribune, gave this account, which he entitled “A Pathetic Incident:”

Maj. Clifton K. Prentiss, a Baltimorean, was a man of exceptional bravery, a veritable cavalier. On this fateful morning he fell mortally wounded, as with waving sword he urged forward his men, to be the first to mount, with assistance, the enemy’s works.

The following pathetic incident occurred after the enemy had been defeated. Two of the 6th Md. men like many others were going over the field ministering to the wounded without regard to the uniform they wore, came upon a wounded Confederate, who after receiving some water, asked if the 6th Md. was any way near there. The reply was, “We belong to that regiment. Why do you ask?” The Confederate replied that he had a brother in that regiment. “Who is he?” he was asked. The Confederate said, “Captain Clifton K. Prentiss.” Our boys said, “Yes, he is our Major now and is lying over yonder wounded.” The Confederate said: “I would like to see him.” Word was at once carried to Maj. Prentiss. He declined to see him saying, “I want to see no man who fired on my country’s flag.”

Col[onel] Hill, after giving directions to have the wounded Confederate brought over, knelt down beside the Major and pleaded with him to see his brother. When the wayward brother was laid beside him our Major for a moment glared at him. The Confederate brother smiled; that was the one touch of nature; out went both hands and with tears streaming down their cheeks these two brothers, who had met on many bloody fields on opposite sides for three years, were once more brought together.

William Howell Reed, in Hospital Life in the Army of the Potomac, reported on what had become of the wounded Prentiss brothers soon after the battle: “They are now lying in the same tent in the Fiftieth New York Engineer’s camp, and I am glad to say likely to do well.” But that was not to be.

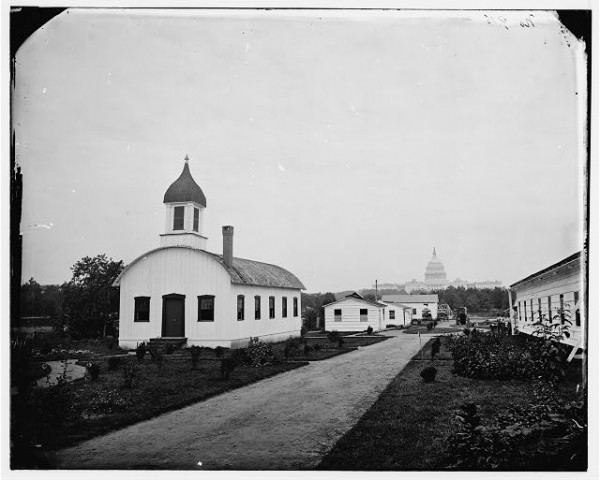

Both Clifton and William Prentiss had been taken to a Union field hospital near Petersburg. While William was held there as a prisoner of war, his shattered right leg was amputated. On May 14, both brothers were transferred to Armory Square Hospital in Washington, D.C., for further treatment.

At Armory Square, a man who described himself as an “Army Hospital Visitor” was waiting. His name was Walt Whitman, destined to become America’s greatest poet. Whitman estimated that he helped 100,000 sick or wounded soldiers in army hospitals during his three years as a volunteer nurse during the Civil War. Whitman wrote about only fifty or so of them. One such entry, for May 28-29, 1865, titled “Two Brothers, One South, One North,” was about these Prentiss brothers, and read as follows:

May 28-9. — I staid to-night a long time by the bedside of a new patient, a young Baltimorean, aged about 19 years, W. S. P., (2d Maryland, southern,) very feeble, right leg amputated, can’t sleep hardly at all — has taken a great deal of morphine, which, as usual, is costing more than it comes to. Evidently very intelligent and well bred — very affectionate — held on to my hand, and put it by his face, not willing to let me leave. As I was lingering, soothing him in his pain, he says to me suddenly, “I hardly think you know who I am — I don’t wish to impose upon you — I am a rebel soldier.” I said I did not know that, but it made no difference. Visiting him daily for about two weeks after that, while he lived, (death had mark’d him, and he was quite alone,) I loved him much, always kiss’d him, and he did me. In an adjoining ward I found his brother, an officer of rank, a Union soldier, a brave and religious man, (Col. Clifton K. Prentiss, sixth Maryland infantry, Sixth corps, wounded in one of the engagements at Petersburg, April 2 — linger’d, suffer’d much, died in Brooklyn, Aug. 20, ‘65.) It was in the same battle both were hit. One was a strong Unionist, the other Secesh; both fought on their respective sides, both badly wounded, and both brought together here after a separa- tion of four years. Each died for his cause.

William died at the Armory Square Hospital on June 24, 1865, and his remains were interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. Clifton, holding out hope for his own recuperation, returned to his home at 35 Livingston Street in Brooklyn. But he died there on August 18, less than two months after his brother had succumbed. Clifton soon was buried next to his brother William, and they have lain side by side, for more than a century, at Green-Wood.

Dear Jeff,

First, thank you for the work you are doing. I see this post is a few years old, but I’m hoping you are still receiving emails from this site.

It is truly amazing and greatly appreciated how much information you are sharing. As someone that enjoys learning about “The War Between the States” (sorry, I couldn’t help myself), and more so, as a Baltimorean, the story about the “Prentiss Brothers” is fascinating.

I’m stumped on one point I hope you could clarify. Unless I’m misreading, it appears that William died first, on June 14, 1865, at the Armory Square Hospital in Washington D.C.

My question is, Why would William be buried in Green-Wood cemetery? I understand the fallen were often buried near where they died, or if the family got the news in time and could it afford they would be shipped home. so how did William end up in Brooklyn? Near Washington D.C. makes sense, as does Baltimore, but Brooklyn?

Thank you for your help, and may you be able to continue doing what is obviously a labor of love.

All the best,

Noah Wollner

A very interesting question. I have not had a chance to research this–will see what I can find about the purchaser of the lot where they are interred. I do know that they had family in Brooklyn–a doctor/uncle, I think.