Note: This is a revised version of an earlier post.

Last Wednesday, I was told that a woman on our regularly-scheduled trolley tour had an original deed to a Green-Wood lot with her, signed by Henry Pierrepont. Pierrepont was the primary mover behind the establishment of Green-Wood Cemetery in 1838, and was its longtime president.

It is always good to learn about Green-Wood from our visitors. So, as the trolley tour ended, I went out to meet this woman. She was very nice, very enthused at Green-Wood, and showed me the deed and two photographs of her ancestors who are interred here. She prefers to remain anonymous.

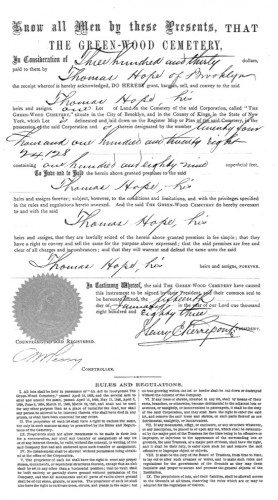

Here’s the deed.

On January 15, 1883 (just slightly more than four months before the Brooklyn Bridge opened), Thomas Hope paid $330 for lot 24128. It was a medium-sized lot, with a border of 189 feet. And the deed routinely included on it printed Rules and Regulations–Green-Wood was taking no chances that a lot owner might go with the “I had no idea” defense to any rules violations. The rules state that “all lots . . . shall not be used for any other purpose than a place of burial for the dead” (no picnics, etc.), that no person “who shall have died in any prison, or shall have been executed for any crime” would be allowed to be interred (not to worry–this rule was regularly waived by cemetery officials), that “proprietors shall not allow interments to be made in their lots for a remuneration” (no selling off a grave here and a grave there), “all monuments and all parts of vaults above ground shall be of cut stone, granite, or marble” (no veneers, no brick), no tree in a lot was to be cut down without cemetery permission, and if a majority of the trustees determined that any monument, enclosure, or structure was “offensive or improper, or injurious to the appearance of the surrounding lots” it shall be removed. Before there was zoning out in the world, Green-Wood had substantial rules and regulations to control what was done on its grounds.

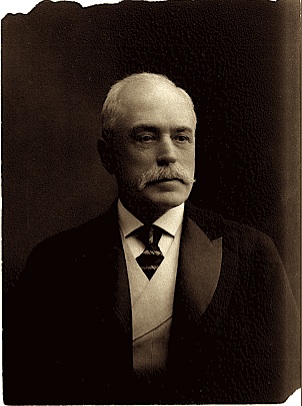

Here is a photograph of Thomas Hope, the lot purchaser.

And this photograph is identified on its back as “Aunt Hattie.”

Looking at Green-Wood’s records, I had concluded, based on the list of those interred in lot 24128, that “Aunt Hattie” was Euterpa A. Hope. According to cemetery records, Euterpa lived at 379 Clinton Street in Brooklyn and died on Feburary 11, 1882 of typhoid fever. She was interred in another Green-Wood lot three days after her death. Exactly one year later, her remains were moved, at Thomas Hope’s request, to lot 24128, the lot that he had just purchased. I thought that perhaps she had been Thomas’s wife–Green-Wood records state that she was married, so Hope appears to have been her married name–and her likely year of birth, 1839, seems to go well as wife/ husband with that of Thomas Hope, who likely was born in 1835).

But then Sue Ramsey, who has worked for years as a tremendous researcher on our Civil War Project, and is a gifted genealogist, read my original blog post on this, was intrigued, and did some research. Sue discovered, based on the census records of 1870 and 1880, that Euterpa was in fact Thomas Hope’s first wife. Sue also discovered that “Aunt Hattie” was in fact Harriet Goodwin Hope–a woman 23 years younger than Thomas Hope when, after Euterpa’s death, they married in 1888. As Sue discovered, Harriet appears with Thomas in the 1900, 1910, and 1920 census records. Indeed, our woman on the trolley has e-mailed to confirm that “Aunt Hattie” was Harriet Goodwin Hope. Now another mystery: there is no Harriet Hope in lot 24128 where Thomas Hope is interred–though there is a Harriet Hope who was interred at Green-Wood in 1933 in another lot. Is that Harriet Goodwin Hope? We don’t know.

I had hoped that a visit to Thomas Hope’s lot would help solve this mystery of who Eutepra A. Hope was and why Harriet Goodwin Hope was not in lot 24128. But that was not to be the case; there are no markers at all in that lot. So, at least for now, the mysteries remain.

Lot owner Thomas Hope, a native of Manchester, England, last lived at 943 President Street in Brooklyn. He would not need a grave in his cemetery lot for quite some time–he lived to be 87 years old, and died in 1922.

Thanks to the woman on the trolley for sharing–and for her permission to use the deed and photographs here. And thanks to Sue Ramsey for more great research.