September 17, 1862, was the bloodiest day in American history. At the Battle of Antietam, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia collided with the Union Army of the Potomac, under the command of Major General George McClellan. By the end of the day, 23,000 American soldiers, North and South, would be killed, wounded, or missing.

On September 17, 2012, one hundred and fifty years after the Battle of Antietam, it was commemorated. And, each state that had men at Antietam then had its own commemoration. I, as Green-Wood’s historian, was honored to be named the coordinator of New York State Day at Antietam. It was held on Sunday, October 21.

Fifty people, some volunteers with Green-Wood’s Civil War Project, others members of the North Shore Civil War Roundtable, journeyed by bus to Antietam National Battlefield to tour and take part in the ceremonies.

Saturday afternoon was spent on the battlefield—licensed Antietam Battlefield Guide William Sagle gave us an overview of the battle. It was then off to the Pry House Field Hospital Museum, where we toured what became, as the battle progressed on that bloody day, a hospital for wound officers. Pry House also was General McClellan’s headquarters during the battle; Bill explained what McClellan had been able to see from there as the battle raged and the tactics that he employed.

On Sunday, I gave a slide talk in the Visitors Center about Antietam and the men who fought there and were ultimately interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. That was followed by our rededication of New York State’s Monument on the battlefield. Bugler Richard Wardlow began the proceedings with “The Star Spangled Banner.” Antietam Battlefield’s historian, Ted Alexander, then described New York State’s sacrifice: it had more men in the battle than any other state; one-forth of all the men who fought for the Union that bloody day were New Yorkers. Of the men from the Empire State, 689 were killed or mortally wounded, 2797 were wounded, and 279 were captured or missing. In all, 27 men who are interred at Green-Wood were killed or mortally wounded that day at Antietam. Wardlow then played the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” I then read the poem that was read over the body of Captain Henry Sand, who was mortally wounded at Antietam, when he was interred at Green-Wood on November 7, 1862:

Breathe not a whisper here,

The place where thou last stand is hallowed ground.

In silence gather near the upheaved ground

Around the soldier’s bier.

Here Liberty may weep,

And Freedom pause in her unchecked career,

To pay the sacred tribute of a tear

O’er the pale warrior’s sleep.

That arm, now cold in death,

But late on Glory’s field triumphant bore

Our country’s flag: that marble brow once wore

The victor’s fadeless wreath.

Rest soldier, sweetly rest.

Affection’s gentle band shall deck thy tomb

With flowers; and chaplets of unfading bloom

Be laid upon thy breast.

Bill Johnson, commanding the honor guard from the 61st New York Infantry, led them as they fired three salutes.

The ceremony concluded with “Taps.”

After the rededication of the New York State Monument, we toured the battlefield, laying a wreath at each of the other New York monuments there (the ten wreaths were paid for by the Civil War Roundtable of New York City and the North Shore Civil War Roundtable). At the monument to the 14th Brooklyn, Robin Heaney, in full mourning garb, depicted a widow of that regiment. She explained the struggle that women went through to try to find their loved ones and, if necessary, to retrieve their bodies for burial back home. Then Robin and a re-enactor from the 14th placed a wreath at the monument. Later, at the Antietam National Cemetery, Robin interpreted Mary Sanford, who is interred at Green-Wood.

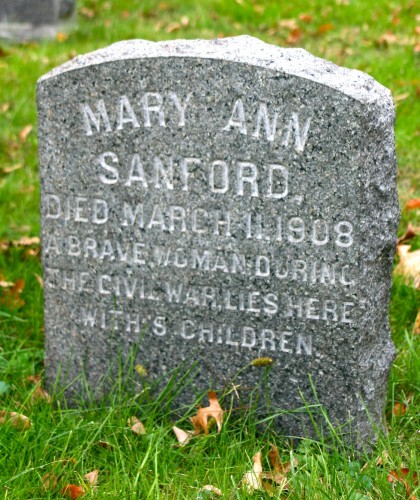

Ten years ago, volunteer Mark Carey found this gravestone at Green-Wood:

This inscription created quite a mystery–who was Mary Sanford–and what did it mean that she was “a brave woman during the Civil War?” A few years ago, one of our volunteers found Mary’s obituary in The New York Times. It described Mary as the wife of a soldier and explained that she had been pressed into service as a nurse at Antietam as the casualties rose.

At Burnside’s Bridge, where the 51st New York fought its way across on its third bloody try, Sue Ramsey, a volunteer from California with our Civil War Project who has been doing great genealogical research for years on the veterans who are interred at Green-Wood, read a letter from Captain Samuel Sims to the widow of Private Thomas Stockwell, describing Stockwell’s death.

Both Sims and Stockwell are interred at Green-Wood. The letter reads:

Headquarters, 51st Regt. N.Y. Vols

Near Village of Antietam MD

Sept 22nd, 1862

Mrs. Thos Stockwell

Dear Madame

It has become my most painful and unavoidable duty to announce to you the death of your husband. He was killed while in the faithful discharge of his duty at the storming of Antietam Bridge Maryland in the morning of September 17th 1862. Our joy at gaining the victory that day has been restrained by our remembrance of the brave men who fell—the faces of our comrades once so familiar that are lost to us, and more than that, the grief that we know will be brought to the home of our noble brother who has rendered his life a sacrifice to prove his devotion to our country, flag, and constitution. Your husband died at the moment of victory. Our Regiment with the Brigade had been ordered forward by Genl. Burnside to advance to the Bridge where the rebels were posted in strong force. They were the Brigade of sharpshooters called “Toombs Brigade” consisting I believe of Georgia, S. Carolina and Mississippi riflemen. The action lasted about one hour before poor Tom fell. He heard as he died the shout of victory. A noble death! but to you a stroke which I fear no words of mine can render alleviation. I humbly pray to my God that he will be with you in your affliction.

His grave is in the valley near the bridge, fifteen of his comrades lie there with him. I have caused an inscription to be placed over him. A final statement of his effects will be sent forward today to Washington. I enclose a lock of his hair. If you make application by letter to the Adjutant General at Washington you will get information as to the final settlement with the government. There are parties in New York who assist in procuring these settlements. If you make application to the Adjt. Genl Major LeGendre of our Regt. who is in New York in Broadway near Reade St. or to Elliott Shepard in Wall St. I regret not being able to give you more information in this reference, but trust that you will find plenty of sympathizing friends who will interest themselves in your behalf. I would suggest Gen. Crooke as a proper adviser.

Again dear madame let me assure you of my deep sympathy in your loss and believe your sincere friend.

Samuel H. Sims

Capt. Co. G, 51st N.Y.

This letter surfaced only recently when Jean Raines, great-granddaughter of Thomas Stockwell, found it in an envelope in her attic. She sent a photocopy of it to Green-Wood and, when I read it, I asked her if she might join us at Antietam and read it at the place where her great-grandfather had died. She had hoped to do so, but family matters made that impossible. So Sue Ramsey, who is a huge fan of Samuel Sims, movingly read it.

We then went to the monument to the Ninth New York Infantry, near where two of Green-Wood’s permanent residents served with great gallantry. Lieutenant Colonel Edgar Addison Kimball, who had also served in the Mexican War, led his men up the hill there. It was Kimball who, when told that his men were running out of ammunition and should retreat, responded, “we have the bayonets. What are they given to us for?” and continued to lead his men forward. His charge represented the farthest point that the Union men reached that day before they were driven back by Confederate reinforcements. It was also there that Captain Adolfe Libaire, after the entire regimental Color Guard had been shot down, grabbed the flag and led the charge. Libaire was awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery.

And, it was on the left of the Ninth that Captain Henry Augustus Sand of the 103rd New York, as he led the charge of his regiment, was shot down. Sand, with his leg shattered, took off his hat and waved it over his head, urging his men to ignore him and move ahead. And, it was from there that he wrote this letter:

Battlefield Near Sharpsburg, Maryland

September 17, 1862

Dear Ma,

Here I lay on the field, shot through the thigh. My wound is painful but not mortal I believe—however I send you these lines to bid you all good bye in case I never see you again.—I hear our men cheering & hope the day is ours—if we only have a great victory, I am contented. Goodbye. My love and kiss to all.

Your loving son,

Henry

Henry Sand’s mother and sister came to Sharpsburg and attempted to nurse him back to health. But, despite their efforts, after six weeks of suffering, he died on the evening of October 30, holding his mother’s hand.

After touring Antietam Battlefield for the entire day, we visited Harpers Ferry the next day. We were very fortunate to have Harpers Ferry National Historical Park’s Chief Historian Dennis Frye as our guide. Dennis, who grew up on a nearby mountain, brought a great passion and an encyclopedic knowledge to his description of the siege and surrender that had occurred there as a prelude to the Battle of Antietam. Here, Dennis describes Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s strategy to take Harpers Ferry–and how that set up the Battle of Antietam that soon followed:

It was quite the three days-a very memorable and moving trip for all of us!