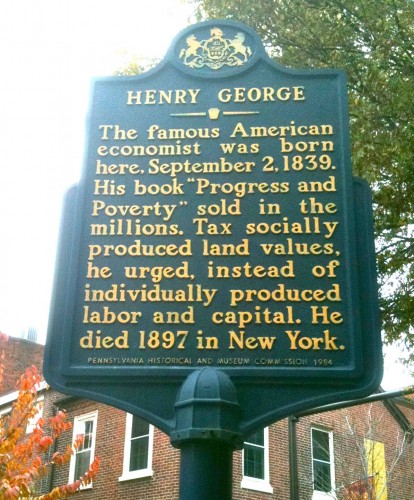

Henry George (1839-1897) came a long way. Born into a middle class Philadelphia family,

he left school at the age of 14, ending his formal education, to work as an errand boy. He worked for years, and was long penniless. But he became a writer, and began to earn a living. Struck by the post-Civil War widening of the gap between rich and poor, he wrote Progress and Poverty, “an inquiry into the cause of industrial depressions and of the increase in want with increase in wealth.” In it he championed a “single tax” on land to alleviate inequities.

Once he got his book published (early on, he could not find a publisher, so he set the type himself), it was a huge hit. In its first year in print, Progress and Poverty sold two million copies. The simplicity of his tax theory–one and only one flat tax–made it an international best-seller; only the Holy Bible sold more copies.

In 1880, Henry George moved to New York City, where he championed the cause of workers and became immensely popular. He ran for mayor in 1886, was criticized as the “apostle of anarchy,” and lost to Abram Hewitt (also a Green-Wood permanent resident), but got more votes than the Republican candidate, Theodore Roosevelt.

After George died of a stroke in 1897, more than 100,000 paid their respects at his bier. Thousands accompanied his body to Green-Wood.

Today, Henry George is remembered as a great 19th century reformer. And he is indeed remembered: with flat tax plans being proposed by Republican presidential candidates, George has been in the news recently. The New York Times, just two weeks ago, ran this piece on Henry George and his relevance to current economic discussions. And, as Occupy Wall Street continues to shine a spotlight on economic inequities, just as Henry George did more than a century ago, his theories also are relevant to that discussion.