George Catlin (1796-1872) devoted much of his life to painting the American Indian. Starting in the 1820s, he went west to paint men and women whom he believed to be on the edge of extinction. He went west for years at a time, driven by his dream and his mission. He painted many tribes, including the Sioux, Osage, and Comanche. He was the only outside artist to draw several other tribes before they disappeared from the face of the earth. And he became internationally famous as a painter and chronicler of Indians.

Now, as you might imagine, Catlin’s extended absences from home, leaving his wife and children behind, and his periodic bankruptcies, did not endear him to his in-laws, the Gregory family. When Catlin died in 1872 in Jersey City, he was briefly interred in a cemetery there, then was transferred to Green-Wood, where the Gregory lot was (section 60, lot 718). A debate then ensued–did the Gregorys even want Catlin in their lot? After Catlin’s remains had stayed in Green-Wood’s Receiving Tomb for months, they were interred at the back of the Gregory lot, without a marker. So much for fame when your in-laws don’t like you. It was not almost a century later that a proper gravestone was placed over Catlin’s remains. But even that marker fails to adequately identify the famous man interred there;

the only inscriptions on it are this on the front: “GEORGE CATLIN 1796-1872,” and this on the back: “THIS MONUMENT WAS ERECTED BY THE NEW YORK WESTERNERS AND MEMBERS OF THE CATLIN FAMILY.” Nothing identifying him as one of America’s most famous 19th century painters, nothing telling the passerby that he was an artist.

Now fast forward to the spring of 2009, at the National Sculpture Society Weekend in Colorado. Rich Moylan, Green-Wood’s president, went on a trip to the Leanin’ Tree Museum of Western Art. There he saw a heroic sculpture of Pariskaroopa (Two Crows), by sculptor John Coleman, based on an 1832 painting by George Catlin. Moylan, with Coleman standing next to him, remarked, “We have him.” A discussion of Catlin’s final resting place ensued, and Coleman soon generously offered to create and donate a sculpture in honor of Catlin, a man Coleman has described as “the father of western art,” to be placed near Catlin’s grave.

This is, of course, all very exciting. Green-Wood is a great sculpture garden, and a heroic sculpture of an Indian is a great piece for us to add to our collections.

Here is George Catlin’s painting of Black Moccasin, who met the explorers Lewis and Clark in 1804, was given a Peace Medal by them, and asked Catlin, when he met him in 1832, to “carry his regards to Clark in St. Louis.”

This is the maquette of “The Greeter,” the sculpture that John Coleman created to be placed at Green-Wood in honor of George Catlin. This is John Coleman’s description of his sculpture:

My new sculpture, “The Greeter,” is based on an account by Catlin of the time he spent with Black Moccasin, chief of the Hidatsas. Catlin believed the chief to be 100 years old at that time. Black Moccasin shared with Catlin many of his recollections of his meeting with Lewis and Clark. This sculpture is my interpretation of what Black Moccasin may have looked like at that time; a man in his 70’s standing on the bank of the Missouri River, holding his ceremonial pipe and making a welcoming gesture with his eagle fan.

And here is John Coleman with a full-size clay model of his work.

k

k

David Grider, an architect, is working on the placement of this remarkable sculpture next to the Gregory Family Lot, a base for it, and interpretive signage. We await their installation in the next few months.

For more about sculptor John Coleman, look here.

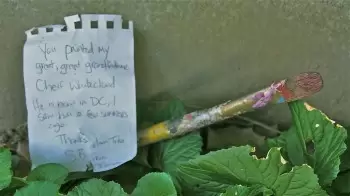

ONE FURTHER NOTE: When I went out last week to Catlin’s gravestone to take a photo of it, I noticed a paint brush at its base. A nice touch, I thought. But when I looked closer, I noticed that there was a small piece of white paper tucked under the brush. Here’s that note, which I propped up against Catlin’s gravestone so I could photograph it. It reads: “You painted my great great grandfather Cheif (sic) Whitecloud. He is now in D.C. I saw him a few summers ago. Thanks. S.B. of the Iowa tribe from Oklahoma.”

And here is Catlin’s painting of White Cloud, owned by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C .

Beautiful article. A long overdue tribute to a great artist, obviously unappreciated by his family. What a legacy he left us. Records of a vanished civilization, that if not for him we would know nothing about.

We are not vanished, we are walking amongst you each and every day. We just don’t look as we did before European contact, but we are STILL HERE.

Eagle Woman , Brooklyn, NY

AS A 12 YEAR OLD CHILD IN THE VILLAGE OF LOUTH IRELAND I LEARNED TO RESPECT THE NATIVE AMERICAN TRIBES;

THE COUNTLESS HOURS SPENT IN AWE OF THE NOBLE WARRIOR ,MADE IMMORTAL BY THE NOBLE ARTIST AND HIS BRUSH—

O! EXHALT HIS NAME ON HIGH !