Well here we are. Not too much spring in the air. It’s not even April yet! But, it is indeed OPENING DAY–time for baseball. And, if you look closely, you’ll see that the harbingers of spring are indeed here: the trees are about to leaf out, the magnolias about to bloom–and the sound of bat against ball is about to reverberate across the land.

So, if it’s baseball’s opening day, can baseball at Green-Wood be far behind? No, it cannot. For those of you who don’t know, Green-Wood Cemetery was a mecca for baseball pioneers. In 2003, Peter Nash, a baseball historian, wrote Baseball Legend’s of Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. Peter, doing extensive research, discovered almost two hundred early baseball players, team owners, equipment manufacturers, and baseball photographers, who chose Green-Wood as their final field of dreams.

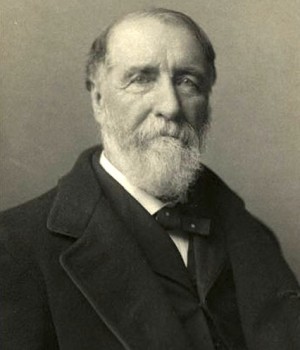

Who have we got on our not-so-active roster of the interred? Well, there’s Henry Chadwick (1824-1908), dubbed the “Father of Baseball” by no less an authority than President Theodore Roosevelt.

Not only did Chadwick invent baseball’s scoring system (pause for a moment, the next time you write 6-4-3 on your scorecard, to remember old Henry) but he also coined some of baseball’s most enduring phrases: assist, base hit, base on balls, cut off, chin music, fungo, white wash, double play, error, goose egg, left on base, and even single. If you know what each and every one of these terms mean, you are quite the baseball fan!

Chadwick is interred at Green-Wood in front of this spectacular monument.

The inscription commemorating Chadwick is appropriately on the diamond-shaped plaque (bases included) on the front of the monument. Crossed bats and a catcher’s mask adorn one side of the monument; crossed bats and an early baseball glove are on the other. A globe is on the top of the monument–a fairly common symbol of eternity in Victorian cemeteries–because a globe has no beginning and no end. But this is a very special globe–it has laces carved into it, making it a very very heavy granite baseball. And look at the ground–Green-Wood’s grounds crew has created base paths connecting each of the markers at the corner of the Chadwick lot–and those markers are carved as bases. One of my favorite tidbits about this monument: the weather was lousy on the date set for its dedication; the dedication was postponed due to rain. Rainchecks, anyone?

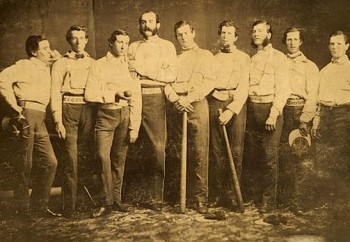

Brooklyn was a hotbed of early baseball–indeed, the story is told that the seeds of baseball as a national sport were planted during the Civil War, when the men of the 14th Brooklyn, serving in the Union Army of the Potomac, taught the game to their comrades from all across America. Those soldiers later returned home and taught the game to others.

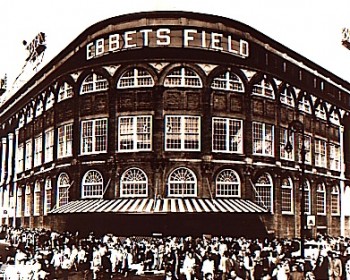

Just over the hill from Henry Chadwick’s grave lies Charlie Ebbets (1859-1925).

Ebbets was chairman of the committee for Chadwick’s monument. But, of course, Ebbets is best known as the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers and as the man who opened his dream, Ebbets Field, in 1913.

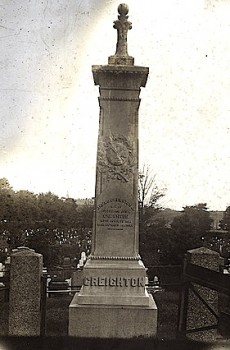

And, on the other side of of Green-Wood lie the remains of James Creighton (1841-1862).

Creighton was baseball’s first superstar. Before Creighton came along, pitchers were supposed to serve the ball up for batters to hit. But Creighton was much too competitive for that: he developed his “wrist throw” and “speedballs,” putting both spin and velocity on his pitches. Not only was Creighton a great pitcher; he was also an amazing hitter–by one account, he went through an entire season without making an out. Can’t do much better than that, can you?

As you may have noticed from Creighton’s life dates above, he was a very young man when he died. By one account, he hit a mammoth home run, ran the bases, then collapsed, having so damaged his innards that he died just a few days later, a victim of his own mighty swing.

Creighton also has a tremendous monument. Here’s a photograph of it from over a hundred years ago. It has downturned bats along its corners, baseball symbols on it, and, in this photograph, is topped by a baseball. Unfortunately that baseball is long gone–if anyone is feeling rich today, we could use the money to replace it.

And, what could be more baseball than the poem “Casey At The Bat.” If I may, here’s the final verse of Ernest Thayer’s classic:

Oh, somewhere in this favoured land the sun is shining bright,The band is playing somewhere,

and somewhere hearts are light;

And somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout,

But there is no joy in Mudville–mighty Casey has struck out.

Now, where do you think the actor who made a career out of reciting “Casey At The Bat” is interred? Correct–William DeWolfe Hopper (1858-1935), the actor who recited this poem on stage 10,000 times before hanging up his spikes, is interred at Green-Wood.

For your entertainment, here’s a movie snippet of Hopper in action–he’s barely warming up here. And, if you are really into it, here’s the entire 1906 Victor Record of his recital. If you’d like to hear Hopper in full throat, start at 5:06 of the video–where he gets his full Casey on.

Next Saturday, April 9, at 1:00 p.m., I will be leading a baseball trolley tour of Green-Wood. It will feature visits to the graves of our baseball men and a slide show of them and their monuments. We might even work in a recording of Hopper’s very over-the-top recitation of “Casey At The Bat.” Seating on our trolley is limited, so please reserve here.

And, if just cannot make it to Green-Wood next Saturday for the tour, you can buy a copy of Peter Nash’s book from our book store; just click here.

And one more thing: Play Ball!