On a fine early spring day recently, I went for a stroll around Green-Wood. Now, one of the virtues of such a wander is that, even after years of exploring, there is always something to discover, something you’ve never noticed before. So, as I walked past this monument, I stopped to take a closer look. I’ve known of its existence for years; I’ve just never examined it closely before.

I walked up the steps to it and read the inscription. This monument, as its inscription states, commemorates a great tragedy: young Andrew Culver, just 17 years old, with his life before him, drowned in Exeter, New Hampshire on May 16, 1871. (Perhaps he was a student at the famed Phillips Exeter Academy). As I examined the monument, I was impressed by the fine quality of the marble (Carrara?) and its very skilled carving.

The detailing is exquisite–the musket in the back (carefully attached in several places to prevent its being broken loose from the rest of the monument), the pile of books on the right (not just neatly stacked, but moving back and forth; they were being used to learn, not just an untouched pile of books), the globe, the anchor of hope, the rope tucked underneath the plaque that contains the inscription, the buttons on the uniform, the bark on the tree. This monument is rich with symbolism: the globe and books as exploration and learning, the musket and uniform of a warrior, the anchor of hope, and the broken tree (symbolizing a young life that had been cut short before reaching its full maturity).

It was readily apparent that this monument had been carved by a very gifted monument maker. So, I started circling it, look for a signature, a mark of pride, that might have been placed somewhere. And, lo and behold, it looked to me like there might be some lettering along the base on the right side. But the sun wasn’t helping–that entire side was in shadow.

So I decided to use the old mirror trick–retrieving a mirror from my car, I caught the sun’s light and raked it across the place where I thought I was seeing lettering. And, here’s what I saw. Though I couldn’t read the entire signature, I though I could make out this much: —ONI & — OIA NY. Well, I thought, that ampersand was a great clue–there couldn’t be that many New York monument makers who would have that in their company name.

This monument, I assumed, had been carved shortly after young Andrew’s 1871 death. So I checked a business directory for Brooklyn and New York City for 1870 that I have at home. Checked under monument makers: nothing. Checked under marble workers: nothing. That was puzzling. After some thought, it occurred to me: how about sculptors? Might there be a separate listing? Well, indeed there was. And the list contained just one company in New York City with an ampersand in its name, and the letters matched up beautifully: Casoni & Isola at 1155 Broadway. I had gotten the ONI and the OLA, except I had read the L as an I. But, no question about it: a match. Casoni & Isola had created the Culver Monument and had proudly signed it.

So, what could I find out about this firm? Online I discovered a monument that the same firm had created in 1864 or shortly thereafter, upon the death of a Confederate soldier that year who was killed in battle. It is at Prairieville-St. Andrew Episcopal Cemetery in Hale County, Alabama.

The monument is a good deal more primitive than the Culver Monument–the carving is less elaborate–but some of the design elements–the weapon, the narrow trunk-like shape–are similar.

I also came across a letter online, written by John Norton Pomeroy on February 1, 1872, describing his visit to Casoni & Isola’s business, after getting what he considered inflated estimates from sculptors in Boston and New York, the lowest of which was an unsatisfactory $5000. Here’s the relevant part:

Being in New York in the fall, I went into the monumental marble shop of Messrs Casoni & Isola, on Broadway, (you may recollect it) and found them ready to undertake the whole job at a moderate price ending in $2000– they limiting the amount of the expense of tackle and machinery for raising the Statue to $150.–the excess to be paid by us. The work is to be done after a model made here,in Massa-Carrara, Italy. the material is to be “the best Carrara Italian monumental marble” to be “executed in the best class manner and to stand eight feet (8 ft.) when finished”–the job to be completed by the 1st of Jany 1873.

So, not only did Casoni & Isola do fine work, with the model created in Italy, but they also did so at reasonable prices. In today’s money, they were charging about $40,000 for this piece–not bad.

Further research revealed this April 10, 1875 obituary for Vincenzo Casoni in the New York Daily Tribune which gives some great details about his business:

Trow’s New York City Directory for 1876 reveals that Casoni’s partner, referred to above as Mr. Isola, was Pietro T. Isola.

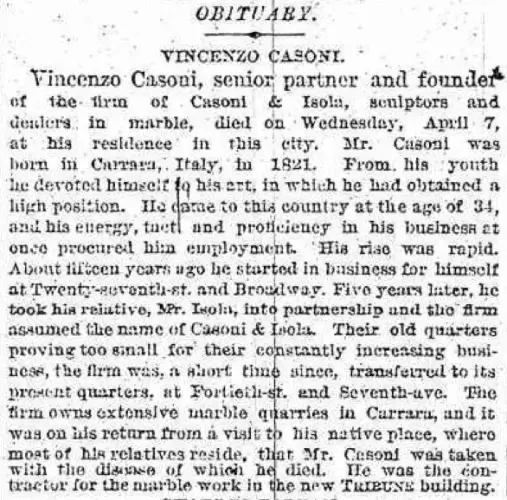

And further research establishes that Casoni & Isola were the fabricators of the famed Seventh Regiment Memorial in Central Park. The monument was designed by sculptor John Quincy Adams War in 1869, the architect Richard Morris Hunt worked on the design of the base, and Casoni & Isola executed the carving. Quite the team of artists! This half-stereoview records the final touches being placed on the Seventh’s monument in 1870.

Is it possible that one of the men in this photograph is Vincenzo Casoni and one of the others is Pietro Isola?

Just by coincidence, I happened to lead an expedition of volunteers up to Woodlawn Cemetery last week. Susan Olsen, Director of Historical Services there, gave us a quick and very delightful tour–and one of the first monuments she pointed out was that to the famed Civil War hero, Admiral David Farragut (“Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”). Susan noted that that elaborate monument was by Casoni & Isola. Wow! Farragut died in 1870, making it likely that this monument was created at about the same time as the Culver Monument at Green-Wood. Here’s an overview and then a detail of the Farragut.

The Culver and the Farragut, by master carvers at the height of their artistic achievement, are very similar in design. Both feature fine detail, carved ropes, a weapon, fabric, ivy (ever-green, symbolic of eternal life) and a round object to give a variety to the shapes.

Susan reports that two other monuments at Woodlawn–those to Gail Borden (condensed milk) and Josiah Macy are also by Casoni & Isola. Her research also reveals that Casoni & Isola collaborated with Italian sculptor Giovanni Benzoni (1809-1873) on a Woodlawn monument–he did the sculpture and they did the base.

One final note. Just to the left of the monument to young Andrew Culver is the monument to another Andrew Culver, likely young Culver’s father. Andrew N. Culver (1832-1906) was a Coney Island pioneer. In the years after his son’s death, he built the first steam railroad to Coney Island, which opened in 1875 and carried one million passengers its inaugural year; by the next year it was carrying two million fares. His Prospect Park & Coney Island Railroad ran on a regular schedule, and gave speedy service for 35 cents. He later added lines out to Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach. His extensive land holdings along these railroads were sold to the big amusement parks, and his railroad franchise was sold to the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company. The branch which that company built along the right of way purchased from him was called the Culver Division (the MTA still uses the designation Culver Line for F and G trains), and the station at Coney Island was known as the Culver Station. Culver Plaza was in the middle of Coney Island.

But, you wonder, did all of the father’s fame and fortune begin to make up for the loss of his son as such a young age? It seems unlikely.

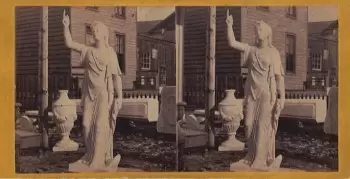

UPDATE: Just came across this. It is a stereoview, published by Edward and Henry T. Anthony at 501 Broadway. Here’s the image: obviously, some very finely carved marble. “Hope” is in the foreground. But also take a look at the urn on the ground–great carving!

And here’s the label on the back of this view. Casoni is misspelled, but, otherwise, it is great to see their work as it was being produced at their yard.

This view dates from the 1860s; this sort of stereoview, with a yellow cardboard mount, was not published until the 1860s. And, if I recall correctly, the Anthonys moved uptown from the address on the label, 501 Broadway, late in the 1860s.

BROOKLYN, BATH & C.I. REACHED C.I. IN 1864.

INTERESTING ARTICLE, THANKS

Thank you for this great article! Pietro is my great-great-grandfather. My family is still trying to find more information about him. This article was very helpful!

Hi Catherine,

Great to hear from you. Glad you enjoyed this post.

Do you have a photograph of Pietro? Any of his carvings?

Interesting article of my father’s grandfathers business. I have some of his sketches. Small, intricate and some beginning to fade. Pietro’s work can also be found in Pepperell, Massachusetts. If you discover other pieces of his work the family would like to know. Thank you.

noticed culver sculpture in the snow, fantastic. love these artisans and looking forward to my next greenwood adventure. I pray while im there, praying is good!

Hi, Suzanne

I have documented grave monuments in Rose Hill Cemetery, Macon, Georgia signed by Casoni & Isola. Let me know if you’d like me to send you photos of the monuments. sashayportraitart@gmail.com.

Excellent Article. In doing reserach for my second book on “Italian Culture in America” my work on the Piccirilli Brothers led me to this wonderful piece of historical reference. You will be cited. – Thanks.

Happy to be of help. Good luck with your book!

Thanks for this article, great information. I am writing an article on Pietro Isola and Italian marble right now. I see a few family members have posted on here, I would LOVE to get in touch with you guys. I am from Pepperell, MA and we live in the “sunset hill” house Isola lived in. Some of you visited my parents years back. I would love to get in touch with you to gain more knowledge on Pietro, I also have gained some information through my research you would like to know. I can be reached at Resurrection.NewEngland@gmail.com or 978-877-7499 Thank you, Jake Cryan