The New-York Historical Society and The Green-Wood Cemetery are two of New York’s oldest institutions. The former was founded in 1804; Green-Wood dates from 1838. In fact, you can tell, just from their spelling, that both go back quite a ways: there was a great passion in the 19th century for hyphens (guidebooks of that era even hyphenated street names–it was spelled Wall-Street back then), reflected both in the early hyphenated spelling, “New-York,” and in “Green-Wood.”

A few weeks ago, I heard from Linda Ferber, vice president and senior art historian at the New-York Historical Society (who I know from having worked with her on an exhibition), and Margaret K. Hofer, the Curator of Decorative Arts there. They were very excited: they had just acquired, through a foundation and individual contributions, a sampler sewn at the New York African Free School in 1820. And, it turns out, Rosena Disery, the school-girl artist of this sampler, is interred with her family at Green-Wood.

Now, this was great news. First of all, I am always up for cooperative efforts with other great institutions, and the New-York Historical Society is one of my favorite places. I have wandered through its galleries for decades (anyone remember all those John Rogers sculptures in the back?) and have done research on Green-Wood’s permanent residents in its great library. Second, one of my pet peeves is that researchers too often fail to consider the cemetery as an important place for research. Our archives, collections, and monuments are unique, and they often provide a lead to a fascinating story. But, unfortunately, few people are aware of the riches we have to offer.

I remember several years ago hosting a book signing at Green-Wood. The author had written a biography of one of our most famous interees. I mentioned to him that, after his talk and signing, the group would be walking out to the lot of the man about whom he had written. He told me that he had never been out there! I was floored–how and why would you devote years to researching a man’s life and not visit his grave?

So, when scholars from the N-YHS wanted to know what we had, I was thrilled. Further, Green-Wood never recorded race in its records, so it has always been a challenge to figure out the race of our permanent residents. In Green-Wood’s early years, in the 1840s, it established Colored Orphan and Colored Adult lots. Those lots still exist. But they quickly fell into disuse, and African Americans were buried across the cemetery grounds, wherever they purchased a lot. That made it very difficult to figure out the race of an individual interred at Green-Wood. But here was information from N-YHS on a young African American woman of the early 19th century–and information in detail–who was interred at Green-Wood. That was great! Finally, I am always up for a good story about a recent purchase (even if I didn’t make the purchase).

So, here is the Acquisition Summary, written by Margaret K. Hofer, Curator of Decorative Arts at the New-York Historical Society (slightly edited for use here), of their recent purchase:

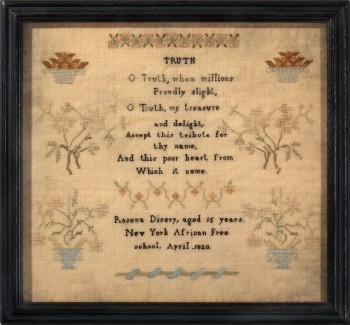

New York African Free School Sampler made by Rosena Disery, April 1820

Silk on wool

Sampler size 12 x 13 in.; frame size 14 x 15 in.

Purchased from: M. Finkel & Daughter, 936 Pine Street, Philadelphia, PA

The New-York Historical Society recently purchased a remarkable needlework sampler, one of only two known to have been made at the New York African Free School. The sampler, stitched by Rosena Disery (1805-1877) in 1820, survives in excellent condition and retains its vivid colors. It features a verse titled “Truth” from the poem “Self-Love and Truth Incompatible,” originally penned by the French mystic Madame Guyon (1648-1717) and translated by William Cowper (1731-1800) in a volume published in London in 1779. Cowper, a critic of slavery, became famous for his poem, “The Negro’s Complaint.” Surrounding the text are Quaker-style motifs, including baskets of fruit, flower urns, and vines.

The New York African Free School was founded by the New York Manumission Society in 1787 to educate free black children to be productive members of society. The first students occupied a single room schoolhouse on Cliff Street, and a new building was erected for the school on William Street in 1814.

In 1791, the AFS added a female instructor to teach needlework to girls. The sewing program was modeled closely on the curriculum at the Female Association Schools, which were organized by New York Quakers to educate young women from families of modest means.

Rosena’s sampler mimics the visual vocabularies of two samplers in the N-YHS collection produced at the Quaker-run schools. Not surprisingly, her instructor, Miss Mary Lincrum, had been educated at a Female Association School.

Student needlework was regularly exhibited at the African Free School’s public examination days as proof of the students’ accomplishments. A schoolgirl’s sampler was akin to her diploma, and would later be proudly displayed in her home. In a valedictory address delivered in 1822, a female pupil declared her indebtedness to her instructor “for what I know of the use of the needle.” She presented her sampler to the teacher, wishing “to leave with you a small piece of my humble performance; it will serve as a testimony of my affectionate regard, and also, as an example to others of my dear schoolmates under your direction, to follow with something in the same way, but I hope, more meritorious.” In addition to improving manual dexterity, the stitching of samplers provided moral instruction and encouraged literacy. According to scholar William Huntting Howell, these samplers embodied a “post-revolutionary political subjectivity” framed in female terms. Young girls demonstrated their capacity for sympathy by emulating fine examples of art and literature in legible stitches, proving their ability to communicate with others in a new republic where it was necessary for citizens to understand one another through common discourses.

Rosena Disery’s sampler is not only notable as a rare example of student work from the African Free School; it is also remarkable that so much is known about the maker’s life subsequent to her education at the AFS. Various records, including those of the Freedman’s Bank, provide important clues about Rosena’s life. The daughter of Nowell and Mary Disery, Rosena married Peter Van Dyke (1796-1869), a successful cook and caterer who owned a house at 133 Wooster Street. City directories indicate that Van Dyke lived there as early as 1853 and remained until his death in 1869. Rosena continued to reside at the house until her death eight years later.

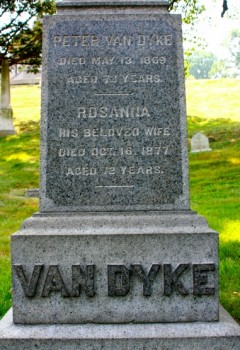

Peter Van Dyke was a prominent figure in New York City’s black community. He merited special mention in Booker T. Washington’s The Negro in Business (1907), which described the success of black caterers and their monopoly of the profession in the mid-nineteenth century. Washington noted: “among those who made fortunes were Peter Van Dyke, who owned a place at 133 Wooster Street. He became wealthy and left his children and grandchildren in good circumstances.” The family’s tremendous financial success is confirmed by numerous sources, including the 1870 census, which records Rosena owning $12,000 in real estate; her deposit of $500 in the Freedman’s Bank in 1871; and her son John’s inheritance of $120,000 at her death in 1877. The family’s meteoric rise is also manifest in the soaring obelisk in Green-Wood cemetery that marks the grave of Peter and Rosena Van Dyke. Sadly, the couple’s son John (1845-1887) quickly squandered the family fortune and became embroiled in a widely publicized domestic dispute.

Rosena Disery’s sampler was first recorded in the seminal book by Ethel Stanwood Bolton and Eve Johnston Coe, American Samplers (1921). Bolton and Coe mentioned that “the sampler was seen in a shop, and unfortunately nothing beyond the name of the girl and name of the school were reported.” The sampler disappeared from public record until just recently, when it was consigned to the leading textile dealer M. Finkel & Daughter of Philadelphia. According to the consignor, the sampler was purchased by a collector at a shop in Texas between 1930 and 1950. Upon the collector’s death, the sampler was bequeathed to her granddaughter, who brought it to the attention of Amy Finkel.

The sampler has been stabilized and conservation mounted in a new frame that replicates the style of the period. A sheet of paper with early nineteenth-century penmanship practice, used to back the needlework, has been separately preserved and accompanies the sampler.

The New-York Historical Society is a fitting repository for the sampler. The library holds the records of the New York African Free School, a significant scholarly resource. The records span the years 1817 to 1832 and include by-laws and reports, observations of the visiting committee, compositions and addresses delivered at public examinations, and penmanship and drawing exercises by students. The reports provide descriptions of the sewing classes, including lists of the instructional levels, the number of girls promoted to each level, and the name of the teacher. The penmanship exercises and drawings are significant documents of the achievements of male students; the sampler is an important addition in representing the endeavors of female pupils at the African Free School. The N-YHS recently launched a new website, “Examination Days: The New York African Free School Collection,” that provides digital images of all the records, scholarly interpretation, and classroom guides for high school teachers.

Rosena Disery’s sampler has great educational potential, and will be soon be programmed both physically and virtually. The sampler will be added to the AFS website and exhibited in the DiMenna Children’s History Museum (opening November 2011) in the pavilion dedicated to James McCune Smith, a contemporary of Rosena’s who attended the African Free School around the same time. It will also be employed in educational programs about slavery in New York. As the work of a teenage African American, the sampler will have great resonance with the school children that the Historical Society endeavors to reach through its programs.

If you would like to read more about the African Free School, here’s the link to the New-York Historical Society’s web pages on it.

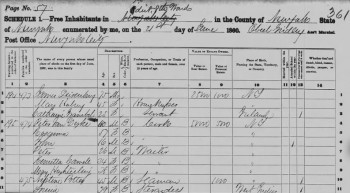

And here’s the 1860 census, listing Rosena and her family. Note that her husband lists real estate valued at $5000 and personal property valued at $5000. It looks like his catering business was going very well–this was a very prosperous family!

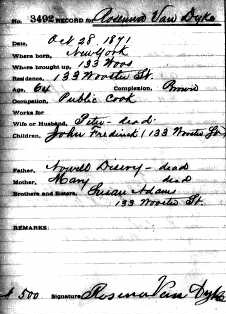

I came across this while doing research on Rosena Disery. Found on Ancestry.com, it is one of the records of the Freedmen’s Bank in New York City. This account dates from October 28, 1871, and was opened by Rosanna Van Dyke–Rosena Disery, now, more than 50 years after she created her sampler, using her married name. She had just deposited $500 into her account. These records include some wonderful information about her and her family. Note her signature at the bottom. Her occupation is listed as “public cook.” Her husband, Peter, is listed as dead; he had died two years earlier.

I found and sent off to the N-YHS photocopies of our records pertaining to Rosena and her family–their ages at death, causes of death, place of birth, marital status, last residence, and even undertaker. And, of course, I must show you Rosena’s final resting place at Green-Wood. She lies in section 21, lot 5819, on a hill overlooking the cemetery’s largest pond, Sylvan Water.

Thanks to Linda Ferber and Margi Hofer for generously sharing their research and this story with me, and allowing me to post it on this blog.

This is beautiful!