Few names from the Civil War are as magical as John Singleton Mosby (1833-1916), “The Gray Ghost” of the Confederacy. Leading his First Virginia Cavalry, widely known as Mosby’s Rangers, in lightning raids against Union forces, then disbursing to local farms, Mosby’s great raids are the stuff of legend. One of his most famous actions occurred on March 9, 1863. Here is Mosby’s own account, from his published memoirs:

When the squads were starting around to gather prisoners and horses, Joe Nelson brought me a soldier who said he was a guard at General Stoughton’s headquarters. Joe had also pulled the telegraph operator out of his tent; the wires had been cut. With five or six men I rode to the house, now the Episcopal rectory, where the commanding general was. We dismounted and knocked loudly at the door. Soon a window above was opened, and some one asked who was there. I answered, “Fifth New York Cavalry with a dispatch for General Stoughton.” The door was opened and a staff officer, Lieutenant Prentiss, was before me. I took hold of his nightshirt, whispered my name in his ear, and told him to take me to General Stoughton’s room. Resistance was useless, and he obeyed. A light was quickly struck, and on the bed we saw the general sleeping as soundly as the Turk when Marco Bozzaris waked him up. There was no time for ceremony, so I drew up the bedclothes, pulled up the general’s shirt, and gave him a spank on his bare back, and told him to get up. As his staff officer was standing by me, Stoughton did not realize the situation and thought that somebody was taking a rude familiarity with him. He asked in an indignant tone what all this meant. I told him that he was a prisoner, and that he must get up quickly and dress.

I then asked him if he had ever heard of “Mosby”, and he said he had.

“I am Mosby,” I said. “Stuart’s cavalry has possession of the Court House; be quick and dress.”

He then asked whether Fitz Lee was there. I said he was, and he asked me to take him to Fitz Lee – they had been together at West Point. Two days afterwards I did deliver him to Fitz Lee at Culpeper Court House. My motive in trying to deceive Stoughton was to deprive him of all hope of escape and to induce him to dress quickly. We were in a critical situation, surrounded by the camps of several thousand troops with several hundred in the town. If there had been any concert between them, they could easily have driven us out; but not a shot was fired although we stayed there over an hour. As soon as it was known that we were there, each man hid and took care of himself. Stoughton had the reputation of being a brave soldier, but a fop. He dressed before a looking-glass as carefully as Sardanapalus did when he went into battle. He forgot his watch and left it on the bureau, but one of my men, Frank Williams, took it and gave it to him. Two men had been left to guard our horses when we went into the house. There were several tents for couriers in the yard, and Stoughton’s horses and couriers were ready to go with us, when we came out with the general and his staff.

When we reached the rendezvous at the courtyard, I found all the squads waiting for us with their prisoners and horses. There were three times as many prisoners as my men, and each was mounted and leading a horse. To deceive the enemy and baffle pursuit, the cavalcade started off in one direction and, soon after it got out of town, turned in another. We flanked the cavalry camps, and were soon on the pike between them and Centreville. As there were several thousand troops in that town, it was not thought possible that we would go that way to get out of the lines, so the cavalry, when it started in pursuit, went in an opposite direction. Lieutenant Prentiss and a good many prisoners who started with us escaped in the dark, and we lost a great many of the horses.

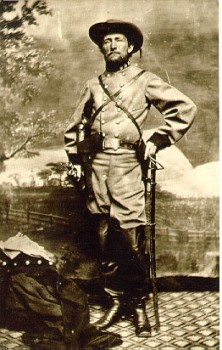

So what does all of this have to do with Green-Wood Cemetery? Mosby is not interred at Green-Wood. Nor is General Stoughton (pictured here). But how about Lieutenant Prentiss, who opened the window, then the door, led Mosby up to Stoughton’s room for the famous spanking, was himself captured, and then escaped? We may be on to something here.

Our Civil War Project has identified 4,500 Civil War veterans at Green-Wood. These identifications have come about in various ways–information from ancestors, newspapers, muster rolls, and much more. One Civil War volunteer in particular, Terry Svensen, has had great success identifying Green-Wood’s Civil War veterans. Terry walks the grounds, looking for gravestones of men who were born in a year that makes it likely that they served in the Civil War. A few weeks ago, Terry was out on the cemetery grounds checking a grave. As he did so, his friend, Barrin Bonet, did some wandering nearby. And Barrin came across this scene:

That looked like a possibility: a man by the name of Samuel F. Prentiss, born in 1842, died in 1894. 1842 indeed was a very good year for the birth of Civil War veterans! So, though it was a very cold day, Terry, urged on by Barrin, took a photograph of Samuel F. Prentiss’s final resting place.

Terry soon did some research. He found that a Samuel F. Prentiss had served with the 13th Vermont Cavalry. Of course, it is not all that likely that a Vermont man would be interred in Brooklyn. But, it does happen on occasion. And, checking pension index records online, Terry discovered that the Samuel F. Prentiss from the 13th Vermont had applied for his post-war pension as a resident of New York State. Interesting. A further check of The New York Times uncovered an 1894 obituary for the Samuel F. Prentiss who is interred at Green-Wood. He had lived in Brooklyn and had worked as a lawyer. But, most importantly, the obituary described his key role in that long ago Mosby raid.

A spanking good find! Sorry, I couldn’t resist . . .