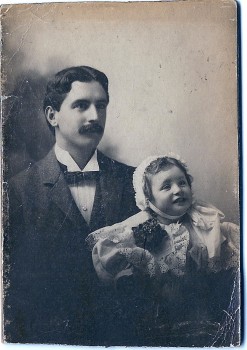

Born in New York State in 1873, Charles A. Armstrong, as a young college graduate, headed out to California to seek has fortune. He settled in San Jose, where he briefly co-owned a bicycle business. There, on New Years Eve, 1894, he married eighteen-year-old Alice Snitzer. In 1897, Charles was off to Arizona on a mining venture. But, when war fever swept the country, he enlisted, on June 7, 1898, at Washington, D.C., in the First Regiment of the United States Volunteer Cavalry, Company C. These were Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, and Charles went off to fight with Roosevelt in the Spanish-American War. Here is a photograph of the handsome Charles and his daughter Bonney, taken soon before his enlistment. Charles mustered into service on June 13 at Tampa, Florida. He then accompanied his unit to Cuba and took part in the famed assault on San Juan and Kettle Hills on July 1, 1898: according to the order of battle, the 1st was on the far right of the attack that day.

Born in New York State in 1873, Charles A. Armstrong, as a young college graduate, headed out to California to seek has fortune. He settled in San Jose, where he briefly co-owned a bicycle business. There, on New Years Eve, 1894, he married eighteen-year-old Alice Snitzer. In 1897, Charles was off to Arizona on a mining venture. But, when war fever swept the country, he enlisted, on June 7, 1898, at Washington, D.C., in the First Regiment of the United States Volunteer Cavalry, Company C. These were Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, and Charles went off to fight with Roosevelt in the Spanish-American War. Here is a photograph of the handsome Charles and his daughter Bonney, taken soon before his enlistment. Charles mustered into service on June 13 at Tampa, Florida. He then accompanied his unit to Cuba and took part in the famed assault on San Juan and Kettle Hills on July 1, 1898: according to the order of battle, the 1st was on the far right of the attack that day.

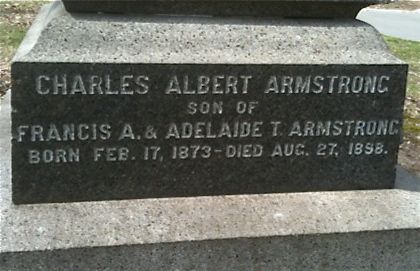

Armstrong was promoted to corporal on July 24, but soon took ill. On August 1, he was confined to quarters due to his contracting a contagious disease, typhoid fever. By August 7, he was at the Hotel Arms in Tampa, Florida, ill with disease. And, on August 25, 1898, he died in a military hospital. Soon thereafter, he was interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in the Armstrong family lot. It undoubtedly was little consolation to his family that more Rough Riders died from diseases they had contracted in Cuba, mostly typhoid fever and malaria, than were killed in battle.

Indeed, Theordore Roosevelt, soon to be vice president and then president of the United States, led the charge up San Juan Hill in Cuba, the turning point of the war, on July 1, 1898. At right is a photograph from the Library of Congress, with this title: “Colonel Roosevelt and his Rough Riders at the top of the hill which they captured, Battle of San Juan. US Army victors on Kettle Hill about July 3, 1898, after the battle of San Juan Hills.” Perhaps Charles is in this photograph.

More than a century later, in 2001, Roosevelt would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his gallantry that day.

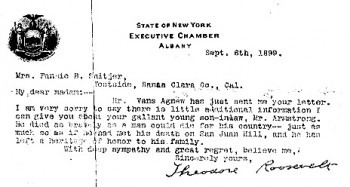

The story of what happened after Charles’s service and his death is quite dramatic. Charles’s mother-in-law began a correspondence with Roosevelt. And Roosevelt, then governor of New York State, wrote back to her. Roosevelt’s letters have descended in Charles’s family, and very generously have been shared by his great granddaughter, Bonney. In the first of three letters, Roosevelt, on September 6, 1899, writes eloquently that Charles Armstrong “died as bravely as a man could die for his country–just as much as if he had met his death on San Juan Hill, and he has left a heritage of honor to his family.”

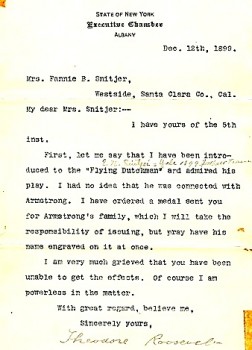

In the second letter, from December of 1899, Roosevelt states that he has ordered and issued a (Rough Rider) medal to commemorate Charles’s service.

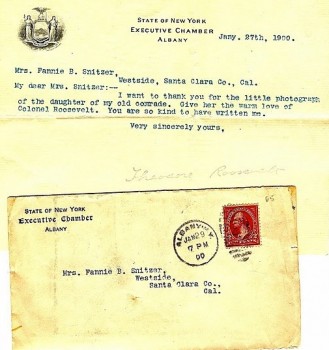

And, in a letter from January, 1900, Roosevelt acknowledges receipt of a photograph of Charles’s daughter, and asks that her grandmother “[g]ive her the warm love of Colonel Roosevelt.”

This correspondence is quite amazing. But even more amazing is what followed. Roosevelt became the Republican Party’s vice presidential candidate in 1900, winning with William McKinley at the head of the ticket. When McKinley was assassinated in 1901, Roosevelt became President of the United States.

Roosevelt, as president, visited San Jose, California, in 1903. Armstrong’s mother-in-law had tried to arrange, through San Jose’s mayor, for Armstrong’s daughter to visit with the president. However, the mayor had decided that it was not possible to arrange such a visit. So, Bonney Armstrong, the young girl, has stood along the president’s route, wearing the Rough Rider medal Roosevelt himself had sent her, and holding a basket of flowers. As Roosevelt was driven past her, he spotted the medal and ordered that his carriage be stopped. Roosevelt visited with the girl and took the basket of flowers she offered him. Soon thereafter, on May 19, 1903, a letter was sent to Bonney by Roosevelt’s secretary, William Loeb, expressing the president’s “cordial thanks” for “the beautiful flowers which you were so kind as to send him.”

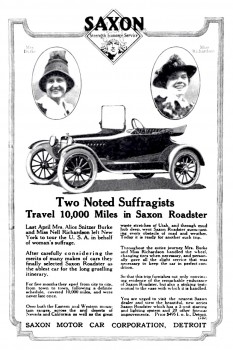

After Charles’s death, his widow, Alice, married a Dr. Burke. She soon became a famous suffragist, Alice Snitzer Burke, traveling the country to promote the cause. Here she is, with her traveling companion, in the car that they toured in. Alice is at the wheel; cities they have visited are listed on the side of the vehicle.

Apparently she made an endorsement deal. At right is the ad for the Saxon Roadster.

And, below is the inscription, memorializing Charles, in the Armstrong family lot near the intersection of Lawn and Vista Avenues in Green-Wood.

YOU HAVE BROUGHT TEARS TO MY EYES….I AM SOOOOO PROUD TO BE HIS GREAT , GRAND-DAUGHTER. THANK YOU FOR PULLING ALL MY INFORMATION TOGETHER AND WRITING THIS MOST LOVELY EULOGY ….WE ARE ALL HONORED….

BONNEY BROWN THOM

GREAT GRAND DAUGHTER OF CHARLES ALBERT ARMSTRONG

MARCH 21, 2011

And thanks to you, Bonney, for bringing this to my attention and sharing all of these wonderful documents, as well as contemporary newspaper accounts. It really is a remarkable story. You should, indeed, be very proud.