Stephanie Carey has been a Green-Wood Historic Fund volunteer since as long as we’ve had volunteers–almost 8 years now. She comes to our Research Days with her husband Mark, and even has brought her daughters along to help out. Stephanie works in New Jersey as a public health professional: she is in charge of communicable disease investigation and containment, as well as food supply safety, sanitation, and safe drinking water “in my corner of Somerset County.” As she researched the 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic, in preparation for very successful efforts last year to contain an H1N1 pandemic, she discovered the story of Dr. William Hallock Park (1863-1939) and that he is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. Stephanie wrote this about Park:

Stephanie Carey has been a Green-Wood Historic Fund volunteer since as long as we’ve had volunteers–almost 8 years now. She comes to our Research Days with her husband Mark, and even has brought her daughters along to help out. Stephanie works in New Jersey as a public health professional: she is in charge of communicable disease investigation and containment, as well as food supply safety, sanitation, and safe drinking water “in my corner of Somerset County.” As she researched the 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic, in preparation for very successful efforts last year to contain an H1N1 pandemic, she discovered the story of Dr. William Hallock Park (1863-1939) and that he is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. Stephanie wrote this about Park:

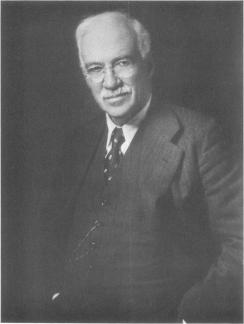

As you walk the grounds of Green-Wood Cemetery, you soon see how common it was for young 19th century children to die. That children no longer die in such large numbers from childhood diseases is due in large part to the work of Dr. William Hallock Park.

A native New Yorker, Dr. Park received his medical degree from Columbia University in 1886. He then traveled to Europe to learn the new science of bacteriology. He knew first hand the toll infectious disease took on children, and was particularly experienced with diphtheria, which killed thousands of children in New York City each year.

In 1893, Dr. Park was appointed director of New York City Health Department’s Bacteriological Diagnostic Laboratory, the first Public Health laboratory in the world. His gift was to develop practical applications for the discoveries being made in the laboratories of Europe. Park invented the means to produce diphtheria antitoxin in large quantities–enough to stop the widespread epidemics that were killing the City’s children. Within a decade, deaths from diphtheria dropped by two-thirds.

“Cholera Infantum”—gastroenteritis– was the top killer of young children at the turn of the last century. Poor sanitation often caused contamination of milk and water supplies. Park’s advocacy led New York to become the first city to regulate the cleanliness of milk being sold within its boundaries. He also pushed for improved treatment of the city’s water supply, halting the spread of typhoid. By 1918, death rates were the lowest in history, and life expectancy was rising dramatically.

Then, in the fall of 1918, soldiers gathered in camps around New York and elsewhere to be deployed to Europe during World War I. In the crowded camps, a deadly flu, “Spanish Influenza”, began to spread rapidly among the soldiers, and out into the surrounding cities. Dr. Park and his colleagues worked around the clock, desperately seeking the bacteria that was causing this deadly epidemic, to find a cure. They were unable to find the cause. It was another decade before scientists proved that flu is caused by a virus. 20,000 New Yorkers, most under the age of 30, died of Spanish Influenza in 8 weeks. But thanks to improvements in public health, it was the last massive epidemic to hit New York City.

William Park, still working at his laboratory until the end, died on April 6, 1939. He is buried with his parents and siblings in their family plot at Green-Wood Cemetery: section 13, lot 9314.

“The greatest gift of the 20th Century is the knowledge that your children will live.”—Steven Gould