It is a remarkable story–a tale of service, sacrifice, research, and discovery.

It is a remarkable story–a tale of service, sacrifice, research, and discovery.

A few months ago I received an e-mail from Kevin Canberg. I didn’t know Kevin, but I was fascinated by his e-mail. Here’s what Kevin wrote:

My father and I have been doing research over the past few months on an old Brooklyn fire badge that was recovered by a relic hunter near Port Hudson, Louisiana, and this research has led me to you. I acquired this badge and was able to identify the owner via a badge register that can be found in the Brooklyn Historical Society. His name was Duncan Richmond. Duncan was a fireman in Brooklyn when he enlisted in the 11th New York (Ellsworth’s Zouaves); was captured during the battle of Bull Run and sent to prison at Charleston, South Carolina, and was released in 1862. Less than a month later he re-enlisted and organized a company of Brooklyn firemen (Franklin Engine 3) to serve with the 159th NY Infantry; he eventually rose to the rank of Captain. Duncan was killed in action during the battle of Cedar Creek in 1864. It is presumed that Duncan wore the badge I now own from the outbreak of war to the time when the 159th was heavily involved in the siege of Port Hudson. Recently, I discovered an article in the Brooklyn Eagle (11/21/2864) that describes Duncan’s funeral, and a burial at Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn – he seems to have been a somewhat prominent Brooklyn resident (he is mentioned by Walt Whitman several times in a collection of Whitman documents housed at Yale University).

My father (himself a Brooklyn FDNY vet and CW buff) and I would very much like to identify where Duncan is buried and visit, but it seems that there is no record of his burial when I search Green-wood’s burial inquiry system on the website. That’s perhaps where you come in. I read about the Civil War project and I’d like to know if Green-wood has any information on Duncan Richmond’s final resting place.

I quickly checked our biographical dictionary of Civil War veterans who are interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. There he was: Duncan Richmond. We had him! I immediately sent an e-mail to Terry Svensen, our Historic Fund volunteer who has taken photographs of the gravestones of the veterans that we have identified. Very soon, Terry e-mailed me a photograph of Duncan Richmond’s gravestone. Here it is. This photograph then went off to Kevin, who, as you can imagine, was thrilled.

I quickly checked our biographical dictionary of Civil War veterans who are interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. There he was: Duncan Richmond. We had him! I immediately sent an e-mail to Terry Svensen, our Historic Fund volunteer who has taken photographs of the gravestones of the veterans that we have identified. Very soon, Terry e-mailed me a photograph of Duncan Richmond’s gravestone. Here it is. This photograph then went off to Kevin, who, as you can imagine, was thrilled.

I find Kevin’s descriptions to be very moving, so, rather than rewrite what he has sent me, here’s how he described his research:

This all started as a Father’s Day gift and turned into one of the most fascinating little research projects I’ve ever embarked on. I vividly remember opening the ancient badge register in the Othmer Library, carefully turning pages until I got to 1170, seeing “Duncan Richmond” and a date the badge was issued…and getting goosebumps when I saw the blank space under “date returned”. My father – who spent years working for the FDNY at Ladder 120 in Brownsville – would especially appreciate it. As he explained to me, a fireman’s badge is a sacred thing – so much so that when he got his own, he locked it away and ordered a replacement for everyday use. So, as a fellow fireman, he considers being the caretaker of Richmond’s badge a deep honor. The fact that he lost it while fighting to preserve the Union – something that cost Richmond the ultimate price – makes it all the more meaningful.

And here’s another recent note from Kevin:

Of course. I wish I could say I was able to locate a photo of [Duncan Richmond] of some kind but the badge is all I have. There’s an obscure book about early civil war prison in Richmond that goes into some detail about soldiers in the 11th New York that were captured after Bull Run and details where they were sent after spending time in Richmond. Duncan and about 30 other guys were sent to Castle Pinckney, South Carolina. There’s a somewhat famous picture of New York fireman who were imprisioned there which I’ve attached. I like to think perhaps that Duncan is among them, but of course I can’t be positive. Just another neat little part of the story.

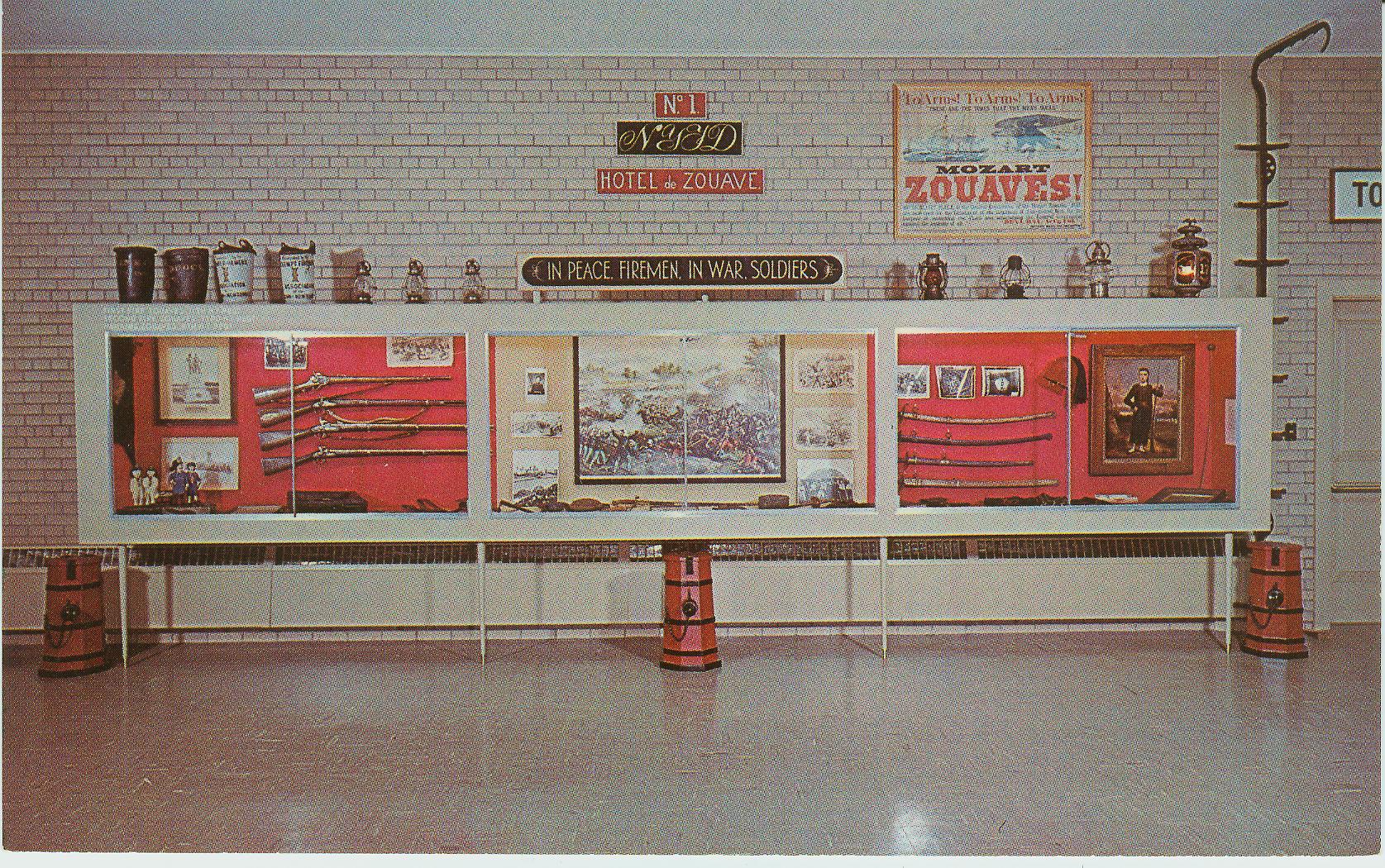

.jpg) UPDATE: I just received an e-mail from Gary Urbanowicz, author of Badges of the Bravest and co-author of The Last Alarm: The History and Tradition of Supreme Sacrifice in the Fire Departments of New York City. Gary had seen this blog post and wanted me to know that the HOTEL ZOUAVE sign that appears in the Castle Pinckney photograph here is now in the collections of the FASNY Museum of Firefighting in Hudson, New York. I visited that museum about 20 years ago–a fascinating place. And, it is located at 117 Harry Howard Avenue–named after Fire Chief Harry Howard, the epitome of the 19th century fire hero, who is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. Here’s the image Gary sent me–with the HOTEL ZOUAVE sign on display at the museum. Amazing that it still exists, almost 150 years after its creation! In this image, it is the red sign in the center top, third down.

UPDATE: I just received an e-mail from Gary Urbanowicz, author of Badges of the Bravest and co-author of The Last Alarm: The History and Tradition of Supreme Sacrifice in the Fire Departments of New York City. Gary had seen this blog post and wanted me to know that the HOTEL ZOUAVE sign that appears in the Castle Pinckney photograph here is now in the collections of the FASNY Museum of Firefighting in Hudson, New York. I visited that museum about 20 years ago–a fascinating place. And, it is located at 117 Harry Howard Avenue–named after Fire Chief Harry Howard, the epitome of the 19th century fire hero, who is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery. Here’s the image Gary sent me–with the HOTEL ZOUAVE sign on display at the museum. Amazing that it still exists, almost 150 years after its creation! In this image, it is the red sign in the center top, third down.

Kevin has generously shared his research on Duncan Richmond with our Civil War Project. So, here’s the biography we now have of Duncan in our biographical dictionary, courtesy of Kevin Canberg, and with thanks to Susan Rudin, our dedicated editor:

DUNCAN. Sergeant, 11th New York Infantry, Company C; captain 159th New York, Company K.

In 1860, Richmond, a Connecticut native who lived at 461 Hicks Street in Brooklyn with his brother and was a silver-plater by trade, left his profession and became a firefighter at the Franklin Engine Company No. 3, located at 53 Henry Street. At the onset of the Civil War on April 20, 1861, he enlisted as a sergeant and mustered into the 11 th New York, also known as the First Fire Zouaves or, most famously, the Ellsworth Zouaves, proudly wearing his firefighters badge on his uniform. According to Kevin D. Canberg, who researched and wrote about Richmond’s life and provided the information for this biography, the regiment was comprised of New York firemen, who were, at the time, considered the strongest and fittest men available to serve in the Union army. Men from Richmond’s firehouse and another nearby firehouse on Remsen Street, were part of Company C. At the Battle of Bull Run, Virginia, at the charge on Henry House Hill on July 21, 1861, he was one of 68 members of his company who were captured and first imprisoned at Richmond, Virginia. He and 10 others were transferred to Castle Pinckney, South Carolina, and held there until they were paroled in May 1862. After mustering out on August 7, 1862, Richmond re-enlisted as a second lieutenant at Brooklyn a month later on September 18, and was commissioned into Company K of the 159 th New York on November 3, recruiting fellow Brooklyn firefighters to fill Company K’s ranks. The 159 th fought at Irish Bend and at the siege of Port Hudson, both along the Mississippi River in Louisiana, as well as smaller engagements throughout the Louisiana region. Richmond never failed to volunteer for hazardous duty (including a near-suicidal assault on Port Hudson dubbed “Forlorn Hope” that Union leadership wisely aborted), earning commendations and praise from his commanding officer. For this courage, he was promoted twice in less than a year: first to first lieutenant on March 1, 1863, effective upon his transfer to Company H and then to captain on February 20, 1864, upon which he returned to Company K. After almost two years of fighting in Louisiana, the 159 th was recalled to Washington, D.C., in July of 1864, and then reassigned to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Richmond led his company through several battles in Sheridan’s decisive campaign, including Third Winchester, Fisher Hill, and Cedar Creek. At Cedar Creek, on October 19, 1864, Richmond was gravely wounded while leading his men in a defense against a Rebel charge on a breastwork behind which his men were positioned. After being removed to a field hospital, he succumbed to his wounds 11 days later. Captain William F. Tiemann wrote about his demise in 159 th New York’s Regimental History, “Captain Duncan Richmond…was also killed, and the loss was most severely felt by the entire regiment. Pleasant and genial in his manner, kind to and thoughtful of his men, brave as the bravest, we could ill afford to lose so gallant an officer. He fell just as success was assured to our arms. None more worthy gave his life for his country.” Richmond’s funeral, complete with much fanfare, was held at Plymouth Church in early November of 1864– even poet Walt Whitman, apparently a neighborhood acquaintance of the Richmond brothers, would make note of the sad event in his diary. The funeral procession, which ran from Plymouth Church along Hicks Street to Richmond’s final resting place at Greenwood Cemetery, was an impressive event that included friends, relatives, a company of New York National Guard troops, Franklin Engine Co. 3, Lodge 288, and the Brooklyn Band. After the Masons, of which he was a master, performed their ancient rites and his fellow soldiers fired a volley, Richmond was buried. Duncan Richmond’s Brooklyn fireman’s badge, which he had worn so proudly into battle, was lost sometime in 1863 in the vicinity of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It remained buried in the Louisiana soil for 145 years until its discovery, worn but intact, in 2008. Acquired by Kevin D. Canberg in 2009, it now resides in the collection of Kevin J. Canberg, Kevin’s father, who like Richmond, served Brooklyn, his home, as a firefighter. Lot 15518.

Do you have information about a Civil War veteran who is interred at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery? If you do, please contact me at jeffrichman@green-wood.com Thanks!

A fascinating article and inspirational. I managed to visit Richmond’s grave while in Brooklyn (I am from Australia). The fabulous Green-wood staff helped me to locate the site. It would bring a sense of closure (to me, and others perhaps?) if there was a photo of Duncan Richmond. I’m wondering if the Masonic Lodge where he was a member might have archived pictures? I’d try to contact them myself, but being so far away…maybe a task for someone closer?

Thank you and best wishes!

Gillian Curtin

I went on the FDNY in’68. My dad was DAC and put me in L-105.His father went on in 1908, died in his sleep, still the senior Lieu. in L-148. My great grandfather, from Ireland, did two five year tours in the US Cav. Back to Brooklyn he became a fireman, A driver, put in the seat of Steamer #5 in Middagh St. Now E-205. I think that I’m the only living 4th generation FDNY guy. I have greatgrandfather’s badge. They told me in Metrotech that they don’t even have one in the NY Fire museum. I assured them that they would when I die. He might be burried in Greenlawn but most of my family is in Holy Cross. He became a Serg. under Gen. Reno out in the Nebraska Terr.and saw action many times with ‘Redskins’ (sic).I have a pic. of him in the seat on the apron of Steamer 5 in 1863. He was all of 31 years old. SW

Four generations! That is quite an accomplishment. Congratulations.

The Flanagans of Harlem and the Bronx are 4th generation firefighters currently and their Dad is also still working in Harlem also. It is quite a tradition and accomplishment.

God Bless Duncan Richmond.

Concerning multi-generational FFs.

The great McKeon family had 4 generations, I believe and may have 5 now

FF. Peter McKeon passed on in Bellevue Hospital on 2/5/1895 after being mortally wounded 3 days previous on 19th Street & Second Ave.

He had 3 generations of FFs after that that served……….including Tom McKeon that served at the World Trade Center, I believe.

A plaque for FF. Pter McKeon is afixed outside the quarters of Engine 5 on 14th street in Manhattan.

This is all from memory…..one not as good as it used to be……..So I hope its on the money.

In any event……God Bless the FDNY!

Jeff, I just posted a comment regarding your research on Chief William Nash when next I read your entry regarding Kevin Canberg and the discovery of the Fireman Duncan Richmonds’ badge. Although I never worked with Kevin Canberg I was the Captain of L-120, FDNY, back in the ’90’s, and remember how odd it was to find a uniform nameplate in my desk the first day I reported for duty. It was named “Canberg”. Back then a lot of guys (including myself) did not want to wear these newly issued nameplates, so I took it for granted that was the reason it was in the desk drawer and not on FF Canbergs’ uniform. For all I know it’s still there. It’s funny how all these stories are somehow connected.

It’s a small world!

As a member of the organization that currently owns Castle Pinckney in Charleston S.C and the groups unofficial historian. I would be very interested in hearing from anyone that may have had either an ancestor that was a prisoner at the Castle during the war, or anyone that may have any historical information about the castle itself, letters documents etc. that they would be willing to share.

Thanking you in advance.

Matthew Locke

Castle Pinckney Historical Preservation Society