A few weeks ago, in preparing for a tour of Civil War Conderates who are interred at Green-Wood, I came across the story of Gilbert Elliott (1843-1895). It is really quite a remarkable tale: Gilbert, with some training in boat building and some experience as a law clerk, enlisted in 1862 in the 17th North Carolina Infantry and was soon appointed first lieutenant and adjutant. But he would spend 1863 on another matter, detailed to build an ironclad ram in a cornfield along the Roanoke River. Elliott wrote about the construction in The Century (July 1888), No vessel was ever constructed under more adverse circumstances. The shipyard was established in a cornfield, where the ground had already been marked out and planted for the coming crop, but the owner of the land was in hearty sympathy with the enterprise, and aided me then and afterwards, in a thousand ways, to accomplish the end I had in view.

A few weeks ago, in preparing for a tour of Civil War Conderates who are interred at Green-Wood, I came across the story of Gilbert Elliott (1843-1895). It is really quite a remarkable tale: Gilbert, with some training in boat building and some experience as a law clerk, enlisted in 1862 in the 17th North Carolina Infantry and was soon appointed first lieutenant and adjutant. But he would spend 1863 on another matter, detailed to build an ironclad ram in a cornfield along the Roanoke River. Elliott wrote about the construction in The Century (July 1888), No vessel was ever constructed under more adverse circumstances. The shipyard was established in a cornfield, where the ground had already been marked out and planted for the coming crop, but the owner of the land was in hearty sympathy with the enterprise, and aided me then and afterwards, in a thousand ways, to accomplish the end I had in view.

It was next to impossible to obtain machinery suitable for the work in hand. Here and there, scattered about the surrounding country, a portable sawmill, a blacksmith’s forge, or other apparatus was found, however, and the citizens of the neighborhoods on both sides of the river were not slow to render me assistance, but cooperated, cordially, in the completion of the ironclad…. Following the designs of Chief Engineer John L. Porter, Elliott completed his work within a year and his ship was named the C.S.S. Albemarle. In describing the construction, Elliott wrote, The work of putting on the armor was prosecuted for some time under the most disheartening circumstances, on account of the difficulty of drilling holes in the iron intended for her armor. But one small engine and drill could be had, and it required, at best, twenty minutes to drill an inch and a quarter hole through the plates, and it looked as if we would never accomplish the task… One of Elliott’s men invented a twist-drill that significantly shortened the drilling process. One of the best constructed vessels of the Civil War, the CSS Albermarle was 152 feet long with a draft of only 9 feet, making it formidable on the seas or shallow inland waterways. Once the project was completed, Elliott resigned on January 20, 1864. The Albemarle soon became a thorn in the side of the Union Navy. She saw action during the Battle of Plymouth on April 19, 1864, ramming and snking the USS Southfield. Union Lieutenant Commander Charles W. Flusser, who commanded the squadron at Plymouth, North Carolina, hunted the Albermarle. But his hunt did not end well for him: when a shell fired from the USS Miami struck the iron plating of the Albemarle in that same engagement, it bounced back onto the Miami, killing Captain Flusser. A sailor on board the Albemarle at Plymouth was impressed by its thick hull and reported that “the noise made by the shot and shell as they struck the boat sounded no louder than pebbles thrown against an empty barrel.” Two weeks later, on May 5, the ironclad survived ramming attacks by Union gunboats with only minor damage. The Albemarle was destroyed by a raid by Union volunteers on the dry docks of North Carolina on October 27 of that year, led by Navy Commander William Cushing, four days before the Union recaptured Plymouth. Three days later, Cushing wrote that he was honored to report that the Albemarle was at the bottom of the Roanoke River. He described how his boat was flooded by a torpedo shot and that after refusing to surrender dove into the water and began to swim ashore. When he emerged from the water at daylight, one of only two raiders who managed to escape safely, he saw two of the Albemarle’s officers, assumed that the vessel had sunk, and soon thereafter verified the information. Cushing won the Medal of Honor for his actions. Eventually the Albemarle was taken to the Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia, in April 1865 where she remained until she was sold in October 1867. Elliott finished his service to the Confederacy on the General Staff of the Army of Northern Virginia. He last lived in Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island.

.jpg) Originally interred in lot 8839, his remains were placed in the current location on November 10, 1895. Section 137, lot 29238. Ironically, just feet from his grave is the grave of Louis Napoleon Stodder, the last surviving officer of the U.S.S. Monitor, which fought the first Confederate ironclad, the C.S.S. Merrimac, to a standstill in the first battle of ironclad ships, and ended the era of wooden warships. Note: Just weeks ago I received an e-mail from a photography dealer I know. Years ago I bought several hundred stereoview photographs of Green-Wood, dating from the 1860’s through about 1900, from him. They are now in the Green-Wood Historic Fund’s collection. In any event, this e-mail told me that this dealer was expanding his website from just auctions to now listing photographs for sale. I didn’t see any harm in taking a look, so I clicked on “19th century photographs” and there was a listing for the C.S.S. Ram Albermarle. Needless to say, that photograph is the one you see here; it is now in the Green-Wood Historic Fund’s collections.

Originally interred in lot 8839, his remains were placed in the current location on November 10, 1895. Section 137, lot 29238. Ironically, just feet from his grave is the grave of Louis Napoleon Stodder, the last surviving officer of the U.S.S. Monitor, which fought the first Confederate ironclad, the C.S.S. Merrimac, to a standstill in the first battle of ironclad ships, and ended the era of wooden warships. Note: Just weeks ago I received an e-mail from a photography dealer I know. Years ago I bought several hundred stereoview photographs of Green-Wood, dating from the 1860’s through about 1900, from him. They are now in the Green-Wood Historic Fund’s collection. In any event, this e-mail told me that this dealer was expanding his website from just auctions to now listing photographs for sale. I didn’t see any harm in taking a look, so I clicked on “19th century photographs” and there was a listing for the C.S.S. Ram Albermarle. Needless to say, that photograph is the one you see here; it is now in the Green-Wood Historic Fund’s collections.

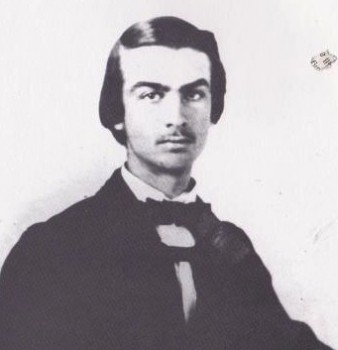

The photograph at the top of this post is of young Gilbert Elliott, teenage ironclad builder. If you would like to read more about Gilbert Elliott and the Albermarle, a descendant has written this book that was published in 1994: Ironclad of the Roanoke: Gilbert Elliott’s Albermarle, by Robert G. Elliot. Or, if you’d like to watch a DVD about Cushing’s heroic raid, you can purchase “The Most Daring Mission of the Civil War” at history.com. Thanks to Susan Rudin, volunteer editor extraordinaire, for her work in helping to write this story.

The owner of that cornfield was my great uncle Peter Evans Smith