On August 27, 1920, the 144th anniversary of the Battle of Brooklyn, the first battle of the American Revolution after the Declaration of Independence was issued and the largest battle of that war, a bronze sculpture of Minerva was unveiled on Green-Wood’s Battle Hill. Battle Hill was a key point in the Battle of Brooklyn–a place of fierce struggle and American triumph during an otherwise disastrous battle.

The primary mover behind the placement of Minerva was Charles Higgins, who had made his fortune in Brooklyn with Higgins India Ink–used back then to fill the fountain pens of the time. Higgins, unhappy that the Battle of Brooklyn had been given short shrift by historians, purchased lots on Green-Wood’s Battle Hill for his family tomb.

But Higgins also had bigger plans–he wanted a suitable monument to the Battle of Brooklyn there. So he purchased the lots in front of his tomb and donated that land for the placement of the Altar of Liberty and a statue of Minerva, the Roman goddess of battle and protector of civilization.

That spot, the highest natural point in Brooklyn, offers spectacular views of lower New York Harbor, New Jersey, the tip of Manhattan, and mid-town Manhattan.

Tour guides have long told visitors that Minerva faces the Statue of Liberty, which had been placed on Liberty Island in 1886, a gift from the French people. And that is indeed the case. But, as we have just learned, it was not always a given that Minerva would be facing, and saluting, her sister in the harbor.

I have long known that Green-Wood’s surveyor, Kestutis Demereckas (“Kostas”), has a collection of blueprints of Green-Wood’s tombs and mausolea in his office. However, as intriguing as they appeared to be, I have never been able to set aside the time to systematically go through them. Now along comes Gabriella, our wonderful volunteer who has a masters in architectural history, to inventory them and note the contents of each plan. As Gabriella has done so, she has made some great finds. She recently was working of those of the Higgins Tomb. And, in processing them, she discovered some fascinating information.

First of all, here are the blueprints for the front elevation of the Higgins Tomb:

And here’s what the Higgins Tomb, faithful to the blueprints, looks like today:

Charles Higgins placed the Altar Of Liberty just in front of his tomb. And, he placed Minerva on it, with her arm upraised, saluting her sister, the Statue of Liberty, in the harbor. Here’s the view from inside Higgins’s tomb.

And here’s a recent view of Minerva in all her glory.

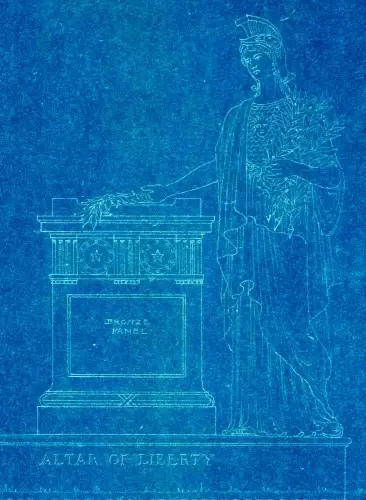

But this is the drawing of Minerva that we found in our files.

This blueprint drawing is a very different Minerva from the one that now stands atop Battle Hill. No upraised arm saluting anything. Body turned to the right, as opposed to the bronze atop Battle Hill with its shoulders straight and parallel to the front and back of the Altar of Liberty. And the flowers being held by Minerva, in her left arm, are also gone by the time the bronze is cast. Even the helmet has changed. And, Minerva’s right arm no longer holds a frond; now it firmly grasps the laurel wreath.

But, most importantly, the issue of where Minerva would face had to be resolved. Well, this is fascinating–take a look at this drawing–in particular, the notation at the left side:

Notice the notation: “FACE N.W. TO THE WOOLWORTH BUILDING.” The Woolworth Building was a recent sensation when Minerva was being planned–it had opened up in 1913, just a few years before Minerva was in her planning stages, with great fanfare as the “Cathedral of Commerce,” the world’s tallest building.

Now take a look at this blueprint and its inscription to the right ,

It says, “POINTING DIRECTLY TO THE STATUE OF LIBERTY.” Now, that’s more like it! Thanks to this change of plans, you now can stand on Battle Hill and see Minerva with her left arm upraised, saluting her sister, the Statue of Liberty, in the distance. And, it appears, the Statue of Liberty, right arm raised, salutes Minerva back.

We have a tendency to look back on the past and conclude that things could only have turned out the way they did turn out. The North won the Civil War–yawn, it was inevitable. But that is not the case at all–the Civil War might well have ended very differently. And, Minerva saluting the Statue of Liberty, as she does now, might well never have occurred –she was destined, at one point, to face elsewhere, with no arm upraised. Not at all inevitable. But much better, the way it turned out.

Quite a find!

The Statue of Minerva and the Higgins Mausoleum are my two favorite places to visit while at Greenwood. I have read about Mr. Higgins’ life. He was a wonderful man.

Thank you so much for this illuminating new information. It serves only to enhance my appreciation and love for Greenwood and those interred within its perimeters.

Thanks Jeff……A fascinating story.

My brother-in-law, NY State Trooper 4790, was buried in Green-wood Cemetery. It was among his final wishes. Much to our surprise, he is in the vicinity of the Statue of Minerva. Green-wood is indeed a spectacular final resting place.

I was thrilled to find this article. As Charles M. Higgins was my grandfathers-father, I am always fascinated when coming across articles such as this. I love learning about my family’s past, and hope to visit Minerva, and the family tomb, in the near future. Thanks!

Happy to share this with you. Certainly a great aspect of Green-Wood is the wonderful stories of its permanent residents. And we fully realize that much of what we know about them comes from descendants who share their knowledge.

Mr Higgins – Having visited that wonderful site a number of years ago , when visiting Brooklyn , I wonder have you any information regards Charles Higgins family in Co Leitrim in Ireland . I am an Irish Historian with an interest in the Famine and the Irish who emigrated to the USA . Thank you Jarlath MacNamara

My Email is gilmoresband@gmail.com

I don’t have that information–but posting your comment in the hopes that someone reading it might . . .