George Catlin (1796-1872), who is interred at Green-Wood, devoted much of his life to painting American Indians and studying their customs. His art and his writing are a remarkable record of their culture and traditions.

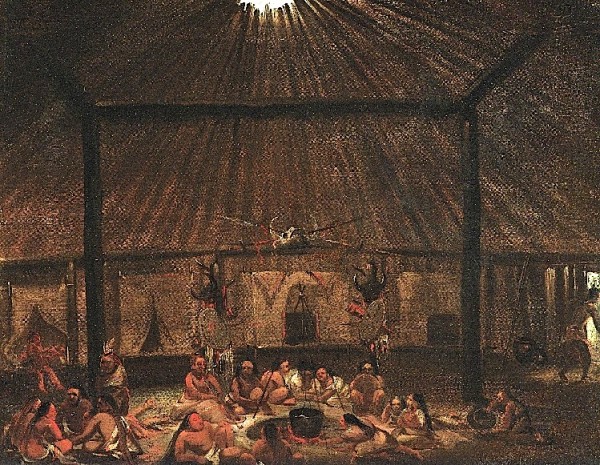

On December 1, 2011, this painting by Catlin, “Interior Of A Mandan Lodge,” consigned by the Field Museum in Chicago (and at one time owned by Benjamin O’Fallon, nephew of William Clark–the Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition), sold at a Sotheby’s auction in New York City for $1,538,500.

In his Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of North American Indians, first published in London in 1844, Catlin writes about the Mandan’s lodges:

The floors of these dwellings are of earth, but so hardened by use, and swept so clean, and tracked by bare and moccassined feet, that they have almost a polish, and would scarcely soil the whitest linen. In the centre, and immediately under the sky-light is the fire-place — a hole of four or five feet in diameter, of a circular form, sunk a foot or more below the surface, and curbed around with stone. Over the fireplace, and suspended from the apex of diverging props or poles, is generally seen the pot or kettle, filled with buffalo meat; and around it are the family, reclining in all the most picturesque attitudes and groups, resting on their buffalo-robes and beautiful mats of rushes. These cabins are so spacious, that they hold from twenty to forty persons — a family and all their connexions. They all sleep on bedsteads similar in form to ours, but generally not quite so high; made of round poles rudely lashed together with thongs. A buffalo skin, fresh stripped from the animal, is stretched across the bottom poles, and about two feet from the floor; which, when it dries, becomes much contracted, and forms a perfect sacking-bottom. The fur side of this skin is placed uppermost, on which tlrey lie with great comfort, with a buffalo-robe f(,ldrcl lip for a pillow, and others drawn over them instead of blankets. These beds, as far as I Irave seen them (and I have visited almost every lodge in the village), are uniformly screenetl with a covering of buffalo or elk skins, oftentimes beautifully dressed and placed over the upright poles or frame, like a suit of curtains; leaving a hole in front, sufficiently spacious for the occupant to pass in and out, to and from his or her bed. Some of these coverings or curtains are exceedingly beautiful, being out tastefully into fringe, and handsomely ornamented with porcupine’s quills and picture writings or hieroglyphics.

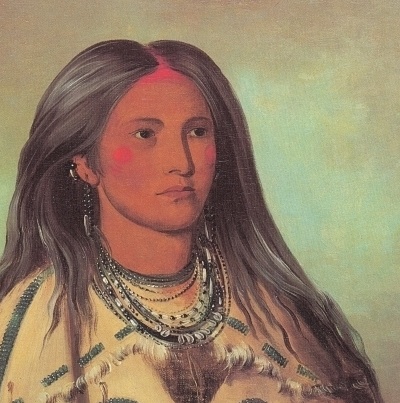

Here is Catlin’s “Portrait of Sha-kó-ka, A Mandan girl,” painted in 1832.

When Catlin visited the Mandan villages, on the Upper Missouri River, from 1832 until 1834, they numbered about 1600 people. However, after smallpox raced through their villages in 1837, their population dipped to about 100. Catlin, who much-admired the Mandan, was shocked when he returned to visit with them thereafter and discovered that they had been so decimated.

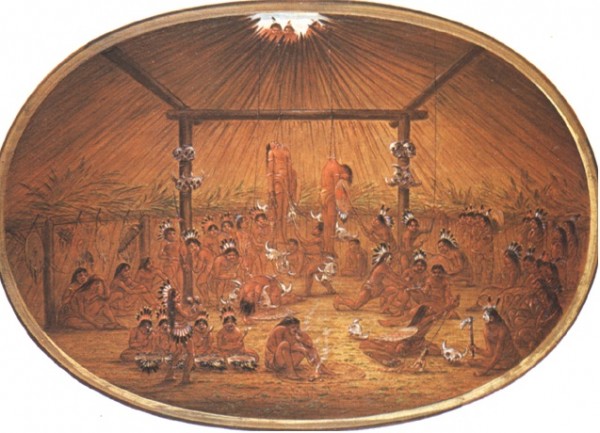

And here is Catlin’s painting of the Mandan’s Okipa ceremony, a test for males involving pain, endurance, and sacrifice, which was central to their rituals:

For my earlier blog post on Catlin, his career, and the bronze sculpture that soon will be placed at Green-Wood, near his grave, to honor him, click here.